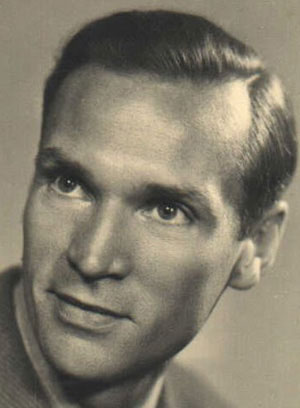

Patrick

Ashe was born on 15 January 1915 in Boudja, Smyrna, Turkey, the youngest

son of the Rev. Robert Pickering Ashe and Edith (Blackler) Ashe. He was

taught by his mother until he was nine years old, and learned to speak

colloquial Greek. In 1922 Smyrna was taken by the Turkish army. To avoid

the pillage and massacre, the British subjects were taken off by the Royal

Navy. He and his parents and two sisters were put on the R.N. Hospital

Ship Main and taken to Malta, where they stayed for some six months as

refugees.

His father, R.P. Ashe, was then offered the Chaplaincy of Cartagena, Spain, where they stayed for two years, and Pat learned to speak Spanish. On their return to Smyrna, they found that all their belongings had been looted. In England, Pat went to a private school, and then to Whitgift School, Croydon as a day boy. In 1934 he went to St. John’s College Cambridge, and read Modern Languages and Theology. He spent one year at Westcott House Theological College, and in 1938 spent a year teaching at Adisadel College, Cape Coast, Gold Coast.

While he was there, the Second World War broke out. He returned to England via the Sahara, and went back to Westcott House to finish his training. He was ordained in l939 in the Diocese of Southwark, and served his title at St. Mary’s Church, Woolwich under the Rector, Cuthbert Bardsley, later Bishop of Coventry. Towards the end of the war he joined the Friends Relief Service, and the team was sent to Cairo where he first met Marion, the daughter of the Very Rev. Francis Johnston. The team was sent to Samos [info - archive views], Greece, working under the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. On his return to England, Pat was made Chaplain to Youth for the Bishop of Southwark.

In 1950 he married Marion (Johnston) Bamber, and he was made Vicar of Blindley Heath, Surrey. He served as Vicar of Otley, Yorks, Vicar of St. Mary’s Leamington Spa, and Rector of Church Stretton, Salop. In 1967 he and Marion started Project Vietnam Orphans. In 1974, in order to concentrate on the work of the Project, he resigned his Living, and they moved to her parents’ old home in Godalming, Surrey. Approximately a hundred children were brought from Vietnam and adopted into Christian homes. After the fall of Vietnam, they started Christian Outreach, which first worked in Thailand, and later in several different countries. Patrick and Marion Ashe have 7 children.

Pat retired in 1980. He became Hon. Domestic Chaplain to Loseley House, and Chaplain at St. Francis, Littleton. Pat and Marion live (from 1974) at Godalming, Surrey. On the occasion of his 90th birthday (15 January 2005), Pat published a limited edition of his book “Dust and Ashes”. It is the story of his walk through life and contains countless examples of how God can make a difference in our lives -- if we let Him.

1- Childhood memories

They staggered into the village of Boudja, near Smyrna in Turkey, the remnants of the British garrison at Kut-el-Amara in Mesopotamia. They had been made to march nearly 2,000 miles from what is now called Iraq to the west coast of Turkey. The British had captured Kut from the Turks in 1915, but later the Turks had surrounded it, starving the garrison into surrender. About 9,000 troops were taken prisoner, and the descriptions of the march by those who survived were horrific. Any who were sick, or too exhausted to walk were bayoneted to death, and left by the roadside for the vultures. One unit straggled into Boudja half-starved, in ragged uniforms, their feet clad in bits of old boot, rags and puttees, and were housed in the Konak, the village police station.

My father was Chaplain to the British community in Boudja, and my parents wanted to get the men something to eat. There was very little food, and we ourselves were only just above subsistence level. Mother gathered together all the food she could, and made a thick soup. We got permission from the guards for the men to come up to the Parsonage for a meal. Father said Grace over what was obviously not enough. It seemed impossible for all of them even to have a little. But as my mother ladled it out, ladle after ladle, including second helpings, still the soup held out. After the meal Father gave thanks for what he believed was a miracle.

Although I was only about two years old, I think I can remember the men coming into the house. It is possible, because my memory goes back vividly to when I was eighteen months old, sitting on the dining room table, and my sisters holding an animal book:

“Pat, where’s the lion?” one of them would say, and I would point.

“Where’s the tiger?”, and I would point at the tiger.

Of course I may remember those prisoners merely as a story which was often told to me. It was my first experience of prayers being answered, and as I look back on my life, I can think of many, many times when God has directly answered prayers.

I remember my first prayers kneeling beside my mother and reciting the names of all the family for God to bless. It was at the time of the Russian Revolution when millions were starving, and my prayers always ended,

“And God bless the Russians, and give them plenty of food to eat.”

I was too young to wonder why one prayer was answered, and another was not.

Those prisoners moved on, but they were not the only British prisoners we saw. One day some British aeroplanes flew in to bomb a Turkish ammunition dump about a mile from where we were living. I remember the crash of the explosions. One plane was shot down, and landed on the race-course. We went and watched from the hill-top. It was a small bi-plane that crash-landed slowly, and the two airmen came out unhurt, holding their revolvers. However, the plane was soon surrounded by Turkish soldiers, and the two airmen gave themselves up.

The Turks interned all British subjects during the first world war. My father was well respected, and although he was not allowed to travel, we were well treated, allowed to live in the Parsonage, and even to spend the summer months in our old windmill outside the village.

Other memories of my childhood stand out like cameos or miniatures - perfect in every detail, yet separated from all that was going on at the time. They are more like photographs in an album than a continuous moving film.

I see the family sitting round the table at lunch on the veranda of the Mill, the summer sun blazing outside. We were all there except Robert, my eldest brother who had volunteered, and was a lieutenant fighting in the army. Round the table were my father and mother, Oliver, Mary, William and Ellen. I was very much the youngest by ten years.

I see the dappling light reflected from the bottom of the galvanised bucket of sparkling water, as my mother dipped it out with a ladle, and poured it into our glasses.

His father, R.P. Ashe, was then offered the Chaplaincy of Cartagena, Spain, where they stayed for two years, and Pat learned to speak Spanish. On their return to Smyrna, they found that all their belongings had been looted. In England, Pat went to a private school, and then to Whitgift School, Croydon as a day boy. In 1934 he went to St. John’s College Cambridge, and read Modern Languages and Theology. He spent one year at Westcott House Theological College, and in 1938 spent a year teaching at Adisadel College, Cape Coast, Gold Coast.

While he was there, the Second World War broke out. He returned to England via the Sahara, and went back to Westcott House to finish his training. He was ordained in l939 in the Diocese of Southwark, and served his title at St. Mary’s Church, Woolwich under the Rector, Cuthbert Bardsley, later Bishop of Coventry. Towards the end of the war he joined the Friends Relief Service, and the team was sent to Cairo where he first met Marion, the daughter of the Very Rev. Francis Johnston. The team was sent to Samos [info - archive views], Greece, working under the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. On his return to England, Pat was made Chaplain to Youth for the Bishop of Southwark.

In 1950 he married Marion (Johnston) Bamber, and he was made Vicar of Blindley Heath, Surrey. He served as Vicar of Otley, Yorks, Vicar of St. Mary’s Leamington Spa, and Rector of Church Stretton, Salop. In 1967 he and Marion started Project Vietnam Orphans. In 1974, in order to concentrate on the work of the Project, he resigned his Living, and they moved to her parents’ old home in Godalming, Surrey. Approximately a hundred children were brought from Vietnam and adopted into Christian homes. After the fall of Vietnam, they started Christian Outreach, which first worked in Thailand, and later in several different countries. Patrick and Marion Ashe have 7 children.

Pat retired in 1980. He became Hon. Domestic Chaplain to Loseley House, and Chaplain at St. Francis, Littleton. Pat and Marion live (from 1974) at Godalming, Surrey. On the occasion of his 90th birthday (15 January 2005), Pat published a limited edition of his book “Dust and Ashes”. It is the story of his walk through life and contains countless examples of how God can make a difference in our lives -- if we let Him.

1- Childhood memories

They staggered into the village of Boudja, near Smyrna in Turkey, the remnants of the British garrison at Kut-el-Amara in Mesopotamia. They had been made to march nearly 2,000 miles from what is now called Iraq to the west coast of Turkey. The British had captured Kut from the Turks in 1915, but later the Turks had surrounded it, starving the garrison into surrender. About 9,000 troops were taken prisoner, and the descriptions of the march by those who survived were horrific. Any who were sick, or too exhausted to walk were bayoneted to death, and left by the roadside for the vultures. One unit straggled into Boudja half-starved, in ragged uniforms, their feet clad in bits of old boot, rags and puttees, and were housed in the Konak, the village police station.

My father was Chaplain to the British community in Boudja, and my parents wanted to get the men something to eat. There was very little food, and we ourselves were only just above subsistence level. Mother gathered together all the food she could, and made a thick soup. We got permission from the guards for the men to come up to the Parsonage for a meal. Father said Grace over what was obviously not enough. It seemed impossible for all of them even to have a little. But as my mother ladled it out, ladle after ladle, including second helpings, still the soup held out. After the meal Father gave thanks for what he believed was a miracle.

Although I was only about two years old, I think I can remember the men coming into the house. It is possible, because my memory goes back vividly to when I was eighteen months old, sitting on the dining room table, and my sisters holding an animal book:

“Pat, where’s the lion?” one of them would say, and I would point.

“Where’s the tiger?”, and I would point at the tiger.

Of course I may remember those prisoners merely as a story which was often told to me. It was my first experience of prayers being answered, and as I look back on my life, I can think of many, many times when God has directly answered prayers.

I remember my first prayers kneeling beside my mother and reciting the names of all the family for God to bless. It was at the time of the Russian Revolution when millions were starving, and my prayers always ended,

“And God bless the Russians, and give them plenty of food to eat.”

I was too young to wonder why one prayer was answered, and another was not.

Those prisoners moved on, but they were not the only British prisoners we saw. One day some British aeroplanes flew in to bomb a Turkish ammunition dump about a mile from where we were living. I remember the crash of the explosions. One plane was shot down, and landed on the race-course. We went and watched from the hill-top. It was a small bi-plane that crash-landed slowly, and the two airmen came out unhurt, holding their revolvers. However, the plane was soon surrounded by Turkish soldiers, and the two airmen gave themselves up.

The Turks interned all British subjects during the first world war. My father was well respected, and although he was not allowed to travel, we were well treated, allowed to live in the Parsonage, and even to spend the summer months in our old windmill outside the village.

Other memories of my childhood stand out like cameos or miniatures - perfect in every detail, yet separated from all that was going on at the time. They are more like photographs in an album than a continuous moving film.

I see the family sitting round the table at lunch on the veranda of the Mill, the summer sun blazing outside. We were all there except Robert, my eldest brother who had volunteered, and was a lieutenant fighting in the army. Round the table were my father and mother, Oliver, Mary, William and Ellen. I was very much the youngest by ten years.

I see the dappling light reflected from the bottom of the galvanised bucket of sparkling water, as my mother dipped it out with a ladle, and poured it into our glasses.

|

I

see the Mill, standing solid and welcoming, which I think of as my childhood

home; its walls, six or eight feet thick, inside cool as a cave; the

beehive window, like a whitewashed tunnel, with a sill six feet deep

in which I sat curled up and watched the flies.

I see the vineyard in front, and the olive trees with their leaves flashing green and silver, their trunks gnarled and twisted.

I see the two pine trees at the top of the path which led down towards the village and the ‘tsikoudhia’, a tree in front of the Mill. We got so adept at climbing it that we swung from branch to branch like monkeys chasing each other. The bark was worn smooth by the constant rub of hands and bare feet. We never wore shoes at the Mill, and could walk over sharp stones and thistles without feeling it.

The Mill had been built on an ancient burial ground, and standing by the Mill was a large stone sarcophagus that had been dug up some years before. In it they had found a silver olive branch, some glass tear bottles and coins. The workmen digging the vineyard would sometimes come upon ancient graves, two upright stones and one set across, over the head of the body.

I see the vineyard in front, and the olive trees with their leaves flashing green and silver, their trunks gnarled and twisted.

I see the two pine trees at the top of the path which led down towards the village and the ‘tsikoudhia’, a tree in front of the Mill. We got so adept at climbing it that we swung from branch to branch like monkeys chasing each other. The bark was worn smooth by the constant rub of hands and bare feet. We never wore shoes at the Mill, and could walk over sharp stones and thistles without feeling it.

The Mill had been built on an ancient burial ground, and standing by the Mill was a large stone sarcophagus that had been dug up some years before. In it they had found a silver olive branch, some glass tear bottles and coins. The workmen digging the vineyard would sometimes come upon ancient graves, two upright stones and one set across, over the head of the body.

Father

had had a cistern built behind the Mill to catch the water from the

roofs, so that we would not have to carry all our water from the well

which was about 100 yards away. The cistern looked rather like a bandstand,

and in my time it had cracked, so we had had to revert to fetching the

water from the well - a well that never ran dry.

My daughter Ruth had been to Turkey on holiday had gone to visit the place where I lived as a child in a village outside Smyrna. She was describing how it was now a ruin, the house had fallen down, and the old windmill that it was attached to had no roof on it. Then she said, ‘There was a big round hole in the ground - what was that for?’

That brought back to me a flood of memories.

It was the remains of the cistern.

There was no water supply when we bought the old Windmill, so we dug a great hole in the ground, cemented it round, and put a wooden floor over the top with a trap door to let buckets down. Then we put a roof over it to catch the rainwater. The water from the house and from the Mill also ran into the cistern. But the cistern was not enough. In the summer when there was no rain it used to run dry - and then we had an earthquake and it cracked. So we were left with a broken cistern that leaked, and even that was swept away, and all that was left was a big hole in the ground.

Just to continue the story - we hired a man who was a water-finder. He came up with a little forked stick of willow, and walked over the property till the willow suddenly twitched in his hand. He said, ‘If you dig here you will find water.’

Many people shook their heads. Windmills are built on top of hills, and they could not believe we would find water. But we set to work to dig - my father, my brothers and sisters and a man who worked on our vineyards. We dug down, down, down, hauling up bucket after bucket of earth, till we nearly gave up in despair. But then my father hired well-diggers. They went on digging until, looking up from the bottom, the opening looked the size of a penny piece in the sky.

But one day we were rewarded! There came a little trickle of water, living water, and we had a ‘fountain’ - a living well that never ran dry, even in the dryest of summers.

Do you think we would have forsaken our well for an old cracked cistern?

Jeremiah and Paul applied a story like that to spiritual values. ‘My people have forsaken me, the fountain of living waters, and hewed out cisterns, broken cisterns that can hold no water’.

Cisterns may hold water for a time - water that may be good enough for washing and cleaning, but no good for drinking. - no good for life.

Who would forsake a well of living water for a cistern, a broken cistern that can hold no water?? How vividly Jeremiah’s picture of forsaking God for worthless things impressed itself on my child mind. When the well was first dug, they came across a huge bone which turned out to be part of the spine of a dinosaur. It ended up in the museum of the American College.

There was a threshing floor also near the Mill. It was a circle paved with smooth cobble stones on which the wheat would be spread. The threshing was done by a man leading a mule that dragged a heavy door round and round over the wheat. The door had old knives, sharp stones and nails hammered into it, with anything else that would help to chop up and disintegrate the ears of corn. He let the children jump on the door for a ride because it helped to give it weight. It made me giddy, and I have never much liked roundabouts. They would then sweep the corn into one place, and on a windy day toss it into the air. The chaff blew away, and the wheat fell into a heap.

They were happy, though dangerous times. One day a Greek called Mihali burst into the kitchen at the Mill where my mother was cooking. He was terrified. A Turk, drunk and enraged, was after him brandishing a knife.

“Save me, save me”, he croaked in a frightened whisper. My mother quickly pushed Mihali behind the door, and stood in the doorway as the Turk arrived.

“Where is Mihali?”, he shouted.

Mother said, “He was here a moment ago - run!” And the Turk ran off.

Most of the time we lived in the village of Boudja, in the Parsonage, a rambling single storey building with about 12 rooms all on one side of an L-shaped marble hall, looking out onto the garden. It was haunted, the Greeks told us, by an old lady who had gone mad and died there. My sister Mary, who was always a bit psychic, saw her one day sitting in a corner of the drawing room. She seemed quite harmless, and we could sometimes hear unaccountable footsteps clicking down the marble hall at night.

There was a German lady in the village called Mrs. Kramer. She fell sick, and Father went to visit her. She was very frail, and needed milk, and as we had some goats, mother used to take her some milk each day in a jar with a screw top handle. One day, while she was out taking her the milk, there was some trouble in the village, and the soldiers were shooting up the road. We were all very frightened, and kept looking out of the window to see if Mother was all right. I remember seeing her slight, straight figure coming calmly along the road carrying the empty jar. When the soldiers saw who it was, the shooting stopped, and she arrived safely home.

Father was greatly loved by the British community, and highly respected by the Greeks and Turks. The Turks were very honest. If we bought charcoal from a Turk, we just put the sacks in the storeroom, but from others we had to tip out the charcoal to see if there were stones at the bottom of the sack.

The camels used to pass through the village on their way to Smyrna from the interior. They have traveled this route for many thousands of years, a string of ten or twelve camels, always led by a man on a donkey. Often he would be asleep, his head bobbing up and down on his chest with the movement of the donkey. The camels stalked along with their haughty, supercilious sneer. We used to run under them as they went along - at first under the rope that tied them together - that was brave; then under their stomachs - that was very brave; but to run between their back legs - that was heroic!

My daughter Ruth had been to Turkey on holiday had gone to visit the place where I lived as a child in a village outside Smyrna. She was describing how it was now a ruin, the house had fallen down, and the old windmill that it was attached to had no roof on it. Then she said, ‘There was a big round hole in the ground - what was that for?’

That brought back to me a flood of memories.

It was the remains of the cistern.

There was no water supply when we bought the old Windmill, so we dug a great hole in the ground, cemented it round, and put a wooden floor over the top with a trap door to let buckets down. Then we put a roof over it to catch the rainwater. The water from the house and from the Mill also ran into the cistern. But the cistern was not enough. In the summer when there was no rain it used to run dry - and then we had an earthquake and it cracked. So we were left with a broken cistern that leaked, and even that was swept away, and all that was left was a big hole in the ground.

Just to continue the story - we hired a man who was a water-finder. He came up with a little forked stick of willow, and walked over the property till the willow suddenly twitched in his hand. He said, ‘If you dig here you will find water.’

Many people shook their heads. Windmills are built on top of hills, and they could not believe we would find water. But we set to work to dig - my father, my brothers and sisters and a man who worked on our vineyards. We dug down, down, down, hauling up bucket after bucket of earth, till we nearly gave up in despair. But then my father hired well-diggers. They went on digging until, looking up from the bottom, the opening looked the size of a penny piece in the sky.

But one day we were rewarded! There came a little trickle of water, living water, and we had a ‘fountain’ - a living well that never ran dry, even in the dryest of summers.

Do you think we would have forsaken our well for an old cracked cistern?

Jeremiah and Paul applied a story like that to spiritual values. ‘My people have forsaken me, the fountain of living waters, and hewed out cisterns, broken cisterns that can hold no water’.

Cisterns may hold water for a time - water that may be good enough for washing and cleaning, but no good for drinking. - no good for life.

Who would forsake a well of living water for a cistern, a broken cistern that can hold no water?? How vividly Jeremiah’s picture of forsaking God for worthless things impressed itself on my child mind. When the well was first dug, they came across a huge bone which turned out to be part of the spine of a dinosaur. It ended up in the museum of the American College.

There was a threshing floor also near the Mill. It was a circle paved with smooth cobble stones on which the wheat would be spread. The threshing was done by a man leading a mule that dragged a heavy door round and round over the wheat. The door had old knives, sharp stones and nails hammered into it, with anything else that would help to chop up and disintegrate the ears of corn. He let the children jump on the door for a ride because it helped to give it weight. It made me giddy, and I have never much liked roundabouts. They would then sweep the corn into one place, and on a windy day toss it into the air. The chaff blew away, and the wheat fell into a heap.

They were happy, though dangerous times. One day a Greek called Mihali burst into the kitchen at the Mill where my mother was cooking. He was terrified. A Turk, drunk and enraged, was after him brandishing a knife.

“Save me, save me”, he croaked in a frightened whisper. My mother quickly pushed Mihali behind the door, and stood in the doorway as the Turk arrived.

“Where is Mihali?”, he shouted.

Mother said, “He was here a moment ago - run!” And the Turk ran off.

Most of the time we lived in the village of Boudja, in the Parsonage, a rambling single storey building with about 12 rooms all on one side of an L-shaped marble hall, looking out onto the garden. It was haunted, the Greeks told us, by an old lady who had gone mad and died there. My sister Mary, who was always a bit psychic, saw her one day sitting in a corner of the drawing room. She seemed quite harmless, and we could sometimes hear unaccountable footsteps clicking down the marble hall at night.

There was a German lady in the village called Mrs. Kramer. She fell sick, and Father went to visit her. She was very frail, and needed milk, and as we had some goats, mother used to take her some milk each day in a jar with a screw top handle. One day, while she was out taking her the milk, there was some trouble in the village, and the soldiers were shooting up the road. We were all very frightened, and kept looking out of the window to see if Mother was all right. I remember seeing her slight, straight figure coming calmly along the road carrying the empty jar. When the soldiers saw who it was, the shooting stopped, and she arrived safely home.

Father was greatly loved by the British community, and highly respected by the Greeks and Turks. The Turks were very honest. If we bought charcoal from a Turk, we just put the sacks in the storeroom, but from others we had to tip out the charcoal to see if there were stones at the bottom of the sack.

The camels used to pass through the village on their way to Smyrna from the interior. They have traveled this route for many thousands of years, a string of ten or twelve camels, always led by a man on a donkey. Often he would be asleep, his head bobbing up and down on his chest with the movement of the donkey. The camels stalked along with their haughty, supercilious sneer. We used to run under them as they went along - at first under the rope that tied them together - that was brave; then under their stomachs - that was very brave; but to run between their back legs - that was heroic!

|

|

|

2

- Missionary in Uganda

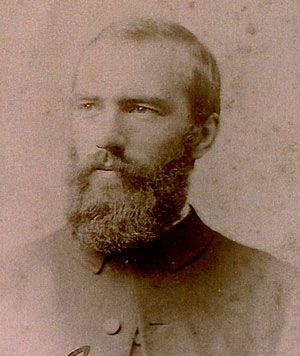

My father, the Reverend Robert Pickering Ashe, MA FRGS, seldom talked about his earlier life in Uganda, except for a few anecdotes. If it were not for his two books, “Two Kings of Uganda” and “Chronicles of Uganda”?, we would have known little about his time there, and I listened attentively to any stories that he told. Father had gone as a missionary to Uganda in 1882 before coming to Smyrna. When Stanley returned from finding Dr. David Livingstone in Central Africa, he wrote a letter to the Daily Telegraph describing Uganda, and suggested that a Christian Mission should be sent there. The Church Missionary Society responded, and sent a group under the leadership of Alexander Mackay, who came to be known as ‘Mackay of Uganda’. All except Mackay died or had to return to England sick, and it was a replacement group that my father joined.

In 1882, when he first went out, he was one of the few who had ventured into the interior of Africa. The controversy over Burton and Speke and the source of the Nile was fresh in people’s minds, and Central Africa was still unexplored. Father drew one of the first maps – hence his nomination as a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society (FRGS). When the small party of Missionaries arrived in Uganda, they had to learn the local language and put it into written form. They had taken out a little printing press, and they taught those who were interested to read, and to learn verses from the Bible. At first they gave away the printed verses, but then they found some thrown away by the roadside. So they made a small charge of some cowry shells for each one, and after that none were thrown away. It is sad that people only seem to appreciate what they have to pay for.

My father, the Reverend Robert Pickering Ashe, MA FRGS, seldom talked about his earlier life in Uganda, except for a few anecdotes. If it were not for his two books, “Two Kings of Uganda” and “Chronicles of Uganda”?, we would have known little about his time there, and I listened attentively to any stories that he told. Father had gone as a missionary to Uganda in 1882 before coming to Smyrna. When Stanley returned from finding Dr. David Livingstone in Central Africa, he wrote a letter to the Daily Telegraph describing Uganda, and suggested that a Christian Mission should be sent there. The Church Missionary Society responded, and sent a group under the leadership of Alexander Mackay, who came to be known as ‘Mackay of Uganda’. All except Mackay died or had to return to England sick, and it was a replacement group that my father joined.

In 1882, when he first went out, he was one of the few who had ventured into the interior of Africa. The controversy over Burton and Speke and the source of the Nile was fresh in people’s minds, and Central Africa was still unexplored. Father drew one of the first maps – hence his nomination as a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society (FRGS). When the small party of Missionaries arrived in Uganda, they had to learn the local language and put it into written form. They had taken out a little printing press, and they taught those who were interested to read, and to learn verses from the Bible. At first they gave away the printed verses, but then they found some thrown away by the roadside. So they made a small charge of some cowry shells for each one, and after that none were thrown away. It is sad that people only seem to appreciate what they have to pay for.

|

Mutesa,

King of Uganda treated them well, and was pleased to have the Missionaries

in his Country, but after he died his son Mwanga became King. He was

young, arrogant and unpredictable. It was he who had a number of the

Christian boys burnt to death. They took them to the edge of a swamp,

hacked off their arms and legs, and threw their bodies alive into the

flames. One little boy begged, “Please don’t cut off my arms - just

throw me into the fire”. Some of the martyrs were singing the hymn:

Daily, daily sing the praises

Of the City God hath made.

O that I had wings of angels

Here to spread, and heavenward fly,

I would seek the gates of Sion

Far beyond the starry sky.

Daily, daily sing the praises

Of the City God hath made.

O that I had wings of angels

Here to spread, and heavenward fly,

I would seek the gates of Sion

Far beyond the starry sky.

|

It

was a terrible experience for the missionaries to lose through such

a horrible death, those whom they loved as their own spiritual children.

Mwanga also ordered the murder of the first Bishop, James Hannington. There had been a tradition that Uganda would be invaded by people coming by the direct eastern route between Uganda and the coast. Hannington did not know of the tradition and came that way instead of going round the south of the Victoria Nyanza. He wrote a diary until the day he was killed.

For a time, Father and Mackay were the only two CMS missionaries left in Uganda, and when Father fell ill, it was decided that he should try and reach the coast. He set off, with a party of bearers carrying his equipment, but soon he was too weak to walk, and knew that he would never survive the journey.

One night a party of Arab traders on their way inland camped near them. They had a strong Muscat donkey which Father saw, and he thought if he could buy it and ride it, he might reach the coast.

He sent one of the men to ask the Arabs whether they would sell the donkey, and for how much. They wanted the equivalent of £30 (which was very expensive for a donkey).

Father tore a page out of his note-book and wrote,

“To the Bank at Zanzibar Pay the bearer of this note - £30.”

And he signed it.

The man took it to the Arabs. The first one said,

“What? Give my donkey for this bit of paper?” and he laughed. But the other Arab said,

“Is he an Englishman?”

Mwanga also ordered the murder of the first Bishop, James Hannington. There had been a tradition that Uganda would be invaded by people coming by the direct eastern route between Uganda and the coast. Hannington did not know of the tradition and came that way instead of going round the south of the Victoria Nyanza. He wrote a diary until the day he was killed.

For a time, Father and Mackay were the only two CMS missionaries left in Uganda, and when Father fell ill, it was decided that he should try and reach the coast. He set off, with a party of bearers carrying his equipment, but soon he was too weak to walk, and knew that he would never survive the journey.

One night a party of Arab traders on their way inland camped near them. They had a strong Muscat donkey which Father saw, and he thought if he could buy it and ride it, he might reach the coast.

He sent one of the men to ask the Arabs whether they would sell the donkey, and for how much. They wanted the equivalent of £30 (which was very expensive for a donkey).

Father tore a page out of his note-book and wrote,

“To the Bank at Zanzibar Pay the bearer of this note - £30.”

And he signed it.

The man took it to the Arabs. The first one said,

“What? Give my donkey for this bit of paper?” and he laughed. But the other Arab said,

“Is he an Englishman?”

clothes given to him by the Sultan of Zanzibar

When

he heard that Father was English, he took the paper, and sent Father

the donkey, which he rode to the coast. Months later the Arabs got back

to Zanzibar - took the paper to the Bank, and got their £30.

There was a time when the word of an Englishman was accepted throughout the world. When I later learnt Spanish, they still had an expression, ‘palabra Ingles’ (Englishman’s word), which they used as one might say, ‘I swear it is true.’

Unfortunately a number of clashes arose between the various religious groups in Uganda which ended in a series of wars. The British finally took over the Country under Lord Lugard, who had been at Rossall School with my father. The British kept the peace until independence in 1962, after which war broke out again under the bloody regime of General Idi Amin.

One less harrowing story, that impressed itself on me, was my father’s encounter with two lions. On his return to Uganda, he had taken the first bicycle ever to reach that part of Africa, and while riding along one day, three lions came bounding out of the bush and ran along beside him. He waved, and shouted, “Come on, my bonny fellows.” After a while they turned off into the bush. Raleigh used that as an advertisement for their cycles, and brought out a poster with my father riding one of them, and the lions running along by his side.

3 - Growing up

To me, those days at the Mill were without a care; the afternoons hot and breathless, the silence broken only by the throbbing buzz of the cicadas in the trees. Early in the morning we would go and gather figs, because it was then they were cold and fresh and succulent. We would also gather grapes which were cooled in a bowl of cold water from the well. Most of the grapes were made into raisins, laid out in bunches on sacking in the sun, and sprinkled with lye-water, made by soaking wood-ash and drawing off the water after the ash had settled. The grapes dried soft and pliable.

When the olives were ripe, the women went and beat the trees with long sticks and gathered the olives from the ground. A few of the best we put in brine for eating, and the rest went down to the press. At the first pressing the oil was pale greeny gold, but later it got thicker and darker with a harsher flavour. The purple black liquid, ‘murga’, that flows from under the oil has a harsh pungent smell that one can never forget. The crushed pips and skin called ‘pirina’ was used as fuel, or to fire lime kilns.

My sister Mary was a beautiful, golden haired girl, with eyes set wide apart and the finest set of teeth I have ever seen. She was something of a tomboy with wrists like steel. Although she was only 5 feet and 3 inches tall, she could take on any of the lads and make them admit defeat. I remember her one day standing on the top of a great heap of stones chanting,

“I’m king of the castle;

Get down you dirty rascal”,

and hurling boy after boy down as they tried to storm it. I was devoted to both my sisters, and even though I must have made their lives a misery, I could not bear to see them hurt. Mary could get me to do anything for her by threatening to cut off her leg. I would howl,

“No, no, don’t cut your leg off. I’ll do whatever you say”.

One evening a group of young people came up to the Mill on their bicycles. One of them said, “Let’s go and steal apricots from Perokakou’s.”

He had a large orchard, and the apricots were falling by the hundred. When I heard they were going I immediately started to whine,

“Take me with you.”

I said it with no hope, but to my amazement they said,

“Yes, all right, you can come too.”

I discovered why I was included. I was small enough to crawl under the wire fence. Then they pointed out which apricots looked nice, and I handed them through the wire.

I was always afraid of being stung by a scorpion. Oliver discovered one in his bed and it stung him. His reaction impressed on me how much it must have hurt. The remedy for a sting was to put a dead scorpion into a bottle of olive oil, and when it had disintegrated, use it as a lotion. They were small gold coloured creatures, and people were often stung on the top of their feet as the scorpion curled its tail up, and stung downwards.

At the back of the Mill were some cottages in which Mustapha and his wife and family lived. He looked after the property, and was a kindly man with deep smile-lines round his sun-baked eyes. His son, Lutvi, who was a great friend of mine, came to a violent end, killed by his little sister. They had come in from hunting, and left the gun leaning against a chair. The little girl went and played with it and pulled the trigger killing him instantly.

My parents taught us never to point. This was a strict rule, and we were roundly scolded even if we pointed a stick. A friend of Williams’s came one night to borrow his revolver. William took out the bullets, but forgot that there was one already in the breech. We were all in the room, and he could easily have pointed it at one of us. He aimed across to the sideboard and pulled the trigger. There was a tremendous bang, and the bullet went through a bottle of vinegar and into the silver teapot. It had a thick cosy on it which prevented the bullet going right through, but it left a deep dent.

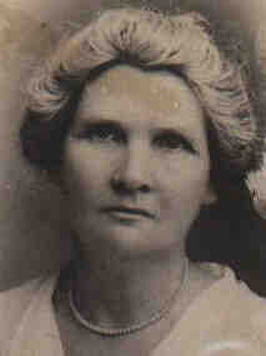

My mother, born Edith Blackler, was the daughter of an American carpet merchant from Marblehead, Massachusetts. She had been born in Smyrna and her mother, Annie Routh, was English, with an enormous family tree going back to de Ruda who came with William the Conqueror. My mother had trained as a teacher, and she taught me at home, but my brothers and sisters had all been to the American College at Paradise, within walking distance of the Mill. Father tried to instill some Latin into my reluctant head. I wish I had paid more attention, but it has been of little more value to me than giving me a few clues as to the meaning of medical terms. Greek was a second language - almost a first, as all my playmates were Greeks. We all spoke a little Turkish, but I soon forgot it through lack of practice. My mother’s sister, Aunt Rose, married Alexander McLachlan, the Principal of the American College [click here to read a segment of his memoirs]. He was one of the first people to have a car in Turkey, a T-model Ford. One day they came to see us in Boudja, and he left the car outside our house on a gentle slope which led down to the Konak. There is a large tree outside the Konak where the policemen often sat in the shade. Some little boys came to stare at the car. Soon a bolder one got in and began to play with the steering wheel and gear knob. He then let off the brake, and as the car began to move, he jumped out, and all the boys ran away. When my uncle came out, the car had gone. He found it at the bottom of the hill with its radiator pushed up against the tree.

In 1921 when I was six, we spent a year in England when Father arranged an exchange with the Vicar of St. Werburg’s, Bristol. On arrival in London, we stayed for a while with an old friend of my father’s. His wife took it upon herself to show Mother how to bring me up properly. I was obedient to my parents, but I would not accept the authority of anyone else. It must have been most embarrassing for my mother, because at meal times the lady would command,

“Say please, or you shan’t get any.”

That made me determined to starve rather than say please, so at each meal I would sit in stubborn silence.

In the hot summers in Turkey I had been used to going to bed late, after the heat of the day had subsided. But this good lady insisted that I go to bed at six o’clock in broad daylight. Screaming my head off, I clung to each rail of the banister, while she prized open my fingers, one by one, dragging me up step by step. By that means I was able to delay bedtime by nearly half an hour.

When we arrived in Bristol, we discovered that the Vicar’s wife and family had decided not to accompany him to Smyrna, so we had to share the Vicarage with them. As it was ‘their’ house, I was supposed to do as they told me, and I was the cause of further disruptions. Mother, with great sweetness and forbearance managed to keep the peace during that year.

I went to a little Kindergarten School for a time, and learnt about the bewildering mysteries of £.s.d. and farthings. Ellen came off worst, as she had to go to a ‘proper’ School, after being a grown-up young lady of sixteen in Smyrna. She did everything she could to get ill so that she would not have to go, but no amount of standing in puddles, and trying to catch cold affected her robust health.

It was a great relief to return to our home in Smyrna.

4 - Turkey for the Turks

In the first world war, Turkey had joined the Germans, and Greece had come in somewhat belatedly on the side of the Allies. After the armistice, Greece was given the task of occupying Turkey. Considering the long-standing hatred between the Greeks and the Turks, it was probably not a wise decision. The Turks had ruled over Greece for some four hundred years, and there were about a million Greeks living in Turkey. Some families had been there since the time of Alexander the Great.

I remember the Greek soldiers full of patriotic zeal, singing songs about Venizelos:

“The cannon roars,

The heart leaps up

To praise the glorious son of Crete.”

and

“Soon we shall take Constantinople,

And Saint Sophia will once more be Greek.”

There were terrible atrocities, Greek villages wiped out by Turks, and Turks tortured and slaughtered in retaliation. The hatred was intense, which was very sad, as Greeks and Turks, Armenians and Jews had lived happily side by side for centuries.

In 1922 the Turks rebelled against the Greek army of occupation. Kemal Ataturk led the victorious Turkish army, and we had rumours of it advancing towards Smyrna. I remember how men from the British community used to gather in the evenings at home to share what news they had gleaned, and to talk over what should be done. They would spread a map on the dining room table, and I remember their serious faces, and their fingers pointing at the map. One evening I hid under the desk, and Mr. Pengelly, a heavily built man, stepped on my finger. My sudden yells nearly gave him a heart attack.

It was at this time that Father put all our silver into a small tin trunk, took up the floor boards in one of the rooms, and asked me as the smallest to go down and push it along under the joists. It was dark under the floor, and there were spiders, and I had not the courage to do it. Ellen squeezed in and pushed it along, and Father put back the boards, and filled in the gaps with earth and dust. When we returned to Smyrna several years later we took up the boards, and the trunk was there intact with the silver. All our other belongings had been looted.

I was seven years old at that time, having been born on 15 January 1915. Late one evening, after I had gone to bed, there was a knock on our front door. It was a naval officer from one of the British warships in Smyrna Bay. He said,

“I don’t want to alarm you, but we think it advisable for you to come onto one of our ships for a day or two until things settle down. Just bring a few things.”

Mother quickly packed some clothes. I dressed, and insisted on taking with me one of Father’s pith helmets from his Uganda days, and a small collapsible candle-lantern in the shape of a book. A special train had been laid on to take us the five miles into Smyrna, and nearly all the British from Boudja were on it. That night we were taken on board one of the warships, and the next day transferred to the Hospital Ship Maine. That was the last we were to see of our home for several years.

The following morning the Turkish Army entered Smyrna. The quays were crowded with Greeks, Armenians and Jews begging to be taken off by the British, French and United States warships. I remember seeing Turkish soldiers killing people and pushing others into the harbour. At first the warships would only take off their own nationals, but later orders were given to take off as many people as possible, and the ships’ boats plied back and forth loaded with refugees. A fire started, and a wind fanned the flames till the whole city blazed. The marble fronts of the houses on the quay remained standing as if to screen the devastation that lay behind. It was never clear who set Smyrna alight - the Greeks said it was the Turks, while the Turks said it was the Armenians, and various other minority groups were accused. It was sad to see the loss of life, and the city burnt to the ground - Smyrna - one of the cities least criticised in the Letters to the Seven Churches in the Revelation of St. John the Divine.

There was a time when the word of an Englishman was accepted throughout the world. When I later learnt Spanish, they still had an expression, ‘palabra Ingles’ (Englishman’s word), which they used as one might say, ‘I swear it is true.’

Unfortunately a number of clashes arose between the various religious groups in Uganda which ended in a series of wars. The British finally took over the Country under Lord Lugard, who had been at Rossall School with my father. The British kept the peace until independence in 1962, after which war broke out again under the bloody regime of General Idi Amin.

One less harrowing story, that impressed itself on me, was my father’s encounter with two lions. On his return to Uganda, he had taken the first bicycle ever to reach that part of Africa, and while riding along one day, three lions came bounding out of the bush and ran along beside him. He waved, and shouted, “Come on, my bonny fellows.” After a while they turned off into the bush. Raleigh used that as an advertisement for their cycles, and brought out a poster with my father riding one of them, and the lions running along by his side.

3 - Growing up

To me, those days at the Mill were without a care; the afternoons hot and breathless, the silence broken only by the throbbing buzz of the cicadas in the trees. Early in the morning we would go and gather figs, because it was then they were cold and fresh and succulent. We would also gather grapes which were cooled in a bowl of cold water from the well. Most of the grapes were made into raisins, laid out in bunches on sacking in the sun, and sprinkled with lye-water, made by soaking wood-ash and drawing off the water after the ash had settled. The grapes dried soft and pliable.

When the olives were ripe, the women went and beat the trees with long sticks and gathered the olives from the ground. A few of the best we put in brine for eating, and the rest went down to the press. At the first pressing the oil was pale greeny gold, but later it got thicker and darker with a harsher flavour. The purple black liquid, ‘murga’, that flows from under the oil has a harsh pungent smell that one can never forget. The crushed pips and skin called ‘pirina’ was used as fuel, or to fire lime kilns.

My sister Mary was a beautiful, golden haired girl, with eyes set wide apart and the finest set of teeth I have ever seen. She was something of a tomboy with wrists like steel. Although she was only 5 feet and 3 inches tall, she could take on any of the lads and make them admit defeat. I remember her one day standing on the top of a great heap of stones chanting,

“I’m king of the castle;

Get down you dirty rascal”,

and hurling boy after boy down as they tried to storm it. I was devoted to both my sisters, and even though I must have made their lives a misery, I could not bear to see them hurt. Mary could get me to do anything for her by threatening to cut off her leg. I would howl,

“No, no, don’t cut your leg off. I’ll do whatever you say”.

One evening a group of young people came up to the Mill on their bicycles. One of them said, “Let’s go and steal apricots from Perokakou’s.”

He had a large orchard, and the apricots were falling by the hundred. When I heard they were going I immediately started to whine,

“Take me with you.”

I said it with no hope, but to my amazement they said,

“Yes, all right, you can come too.”

I discovered why I was included. I was small enough to crawl under the wire fence. Then they pointed out which apricots looked nice, and I handed them through the wire.

I was always afraid of being stung by a scorpion. Oliver discovered one in his bed and it stung him. His reaction impressed on me how much it must have hurt. The remedy for a sting was to put a dead scorpion into a bottle of olive oil, and when it had disintegrated, use it as a lotion. They were small gold coloured creatures, and people were often stung on the top of their feet as the scorpion curled its tail up, and stung downwards.

At the back of the Mill were some cottages in which Mustapha and his wife and family lived. He looked after the property, and was a kindly man with deep smile-lines round his sun-baked eyes. His son, Lutvi, who was a great friend of mine, came to a violent end, killed by his little sister. They had come in from hunting, and left the gun leaning against a chair. The little girl went and played with it and pulled the trigger killing him instantly.

My parents taught us never to point. This was a strict rule, and we were roundly scolded even if we pointed a stick. A friend of Williams’s came one night to borrow his revolver. William took out the bullets, but forgot that there was one already in the breech. We were all in the room, and he could easily have pointed it at one of us. He aimed across to the sideboard and pulled the trigger. There was a tremendous bang, and the bullet went through a bottle of vinegar and into the silver teapot. It had a thick cosy on it which prevented the bullet going right through, but it left a deep dent.

My mother, born Edith Blackler, was the daughter of an American carpet merchant from Marblehead, Massachusetts. She had been born in Smyrna and her mother, Annie Routh, was English, with an enormous family tree going back to de Ruda who came with William the Conqueror. My mother had trained as a teacher, and she taught me at home, but my brothers and sisters had all been to the American College at Paradise, within walking distance of the Mill. Father tried to instill some Latin into my reluctant head. I wish I had paid more attention, but it has been of little more value to me than giving me a few clues as to the meaning of medical terms. Greek was a second language - almost a first, as all my playmates were Greeks. We all spoke a little Turkish, but I soon forgot it through lack of practice. My mother’s sister, Aunt Rose, married Alexander McLachlan, the Principal of the American College [click here to read a segment of his memoirs]. He was one of the first people to have a car in Turkey, a T-model Ford. One day they came to see us in Boudja, and he left the car outside our house on a gentle slope which led down to the Konak. There is a large tree outside the Konak where the policemen often sat in the shade. Some little boys came to stare at the car. Soon a bolder one got in and began to play with the steering wheel and gear knob. He then let off the brake, and as the car began to move, he jumped out, and all the boys ran away. When my uncle came out, the car had gone. He found it at the bottom of the hill with its radiator pushed up against the tree.

In 1921 when I was six, we spent a year in England when Father arranged an exchange with the Vicar of St. Werburg’s, Bristol. On arrival in London, we stayed for a while with an old friend of my father’s. His wife took it upon herself to show Mother how to bring me up properly. I was obedient to my parents, but I would not accept the authority of anyone else. It must have been most embarrassing for my mother, because at meal times the lady would command,

“Say please, or you shan’t get any.”

That made me determined to starve rather than say please, so at each meal I would sit in stubborn silence.

In the hot summers in Turkey I had been used to going to bed late, after the heat of the day had subsided. But this good lady insisted that I go to bed at six o’clock in broad daylight. Screaming my head off, I clung to each rail of the banister, while she prized open my fingers, one by one, dragging me up step by step. By that means I was able to delay bedtime by nearly half an hour.

When we arrived in Bristol, we discovered that the Vicar’s wife and family had decided not to accompany him to Smyrna, so we had to share the Vicarage with them. As it was ‘their’ house, I was supposed to do as they told me, and I was the cause of further disruptions. Mother, with great sweetness and forbearance managed to keep the peace during that year.

I went to a little Kindergarten School for a time, and learnt about the bewildering mysteries of £.s.d. and farthings. Ellen came off worst, as she had to go to a ‘proper’ School, after being a grown-up young lady of sixteen in Smyrna. She did everything she could to get ill so that she would not have to go, but no amount of standing in puddles, and trying to catch cold affected her robust health.

It was a great relief to return to our home in Smyrna.

4 - Turkey for the Turks

In the first world war, Turkey had joined the Germans, and Greece had come in somewhat belatedly on the side of the Allies. After the armistice, Greece was given the task of occupying Turkey. Considering the long-standing hatred between the Greeks and the Turks, it was probably not a wise decision. The Turks had ruled over Greece for some four hundred years, and there were about a million Greeks living in Turkey. Some families had been there since the time of Alexander the Great.

I remember the Greek soldiers full of patriotic zeal, singing songs about Venizelos:

“The cannon roars,

The heart leaps up

To praise the glorious son of Crete.”

and

“Soon we shall take Constantinople,

And Saint Sophia will once more be Greek.”

There were terrible atrocities, Greek villages wiped out by Turks, and Turks tortured and slaughtered in retaliation. The hatred was intense, which was very sad, as Greeks and Turks, Armenians and Jews had lived happily side by side for centuries.

In 1922 the Turks rebelled against the Greek army of occupation. Kemal Ataturk led the victorious Turkish army, and we had rumours of it advancing towards Smyrna. I remember how men from the British community used to gather in the evenings at home to share what news they had gleaned, and to talk over what should be done. They would spread a map on the dining room table, and I remember their serious faces, and their fingers pointing at the map. One evening I hid under the desk, and Mr. Pengelly, a heavily built man, stepped on my finger. My sudden yells nearly gave him a heart attack.

It was at this time that Father put all our silver into a small tin trunk, took up the floor boards in one of the rooms, and asked me as the smallest to go down and push it along under the joists. It was dark under the floor, and there were spiders, and I had not the courage to do it. Ellen squeezed in and pushed it along, and Father put back the boards, and filled in the gaps with earth and dust. When we returned to Smyrna several years later we took up the boards, and the trunk was there intact with the silver. All our other belongings had been looted.

I was seven years old at that time, having been born on 15 January 1915. Late one evening, after I had gone to bed, there was a knock on our front door. It was a naval officer from one of the British warships in Smyrna Bay. He said,

“I don’t want to alarm you, but we think it advisable for you to come onto one of our ships for a day or two until things settle down. Just bring a few things.”

Mother quickly packed some clothes. I dressed, and insisted on taking with me one of Father’s pith helmets from his Uganda days, and a small collapsible candle-lantern in the shape of a book. A special train had been laid on to take us the five miles into Smyrna, and nearly all the British from Boudja were on it. That night we were taken on board one of the warships, and the next day transferred to the Hospital Ship Maine. That was the last we were to see of our home for several years.

The following morning the Turkish Army entered Smyrna. The quays were crowded with Greeks, Armenians and Jews begging to be taken off by the British, French and United States warships. I remember seeing Turkish soldiers killing people and pushing others into the harbour. At first the warships would only take off their own nationals, but later orders were given to take off as many people as possible, and the ships’ boats plied back and forth loaded with refugees. A fire started, and a wind fanned the flames till the whole city blazed. The marble fronts of the houses on the quay remained standing as if to screen the devastation that lay behind. It was never clear who set Smyrna alight - the Greeks said it was the Turks, while the Turks said it was the Armenians, and various other minority groups were accused. It was sad to see the loss of life, and the city burnt to the ground - Smyrna - one of the cities least criticised in the Letters to the Seven Churches in the Revelation of St. John the Divine.

To SMYRNA

Sacked by the Turks (1922) with indiscriminate slaughter of women, children, and civilian men, and then burnt.

Fair widowed city by thy sunlit sea!

Waving with moaning pine and cypress sad,

No longer grape and olive make thee glad,

Thou sittest in the dust in misery.

Beneath the moon thy palid marbles gleam,

Haunted by ghosts of murdered thousands! None

Who watched that deed would help when it was done!

Thy lover, the west wind, wakes not thy dream,

Though whispering to thee with wooing breath,

Sighing through empty streets and blackened walls,

Through ruined churches and in roofless halls.

O city fair still beautiful in death!

Thy ravager shall yet be stricken down,

And thou, a queen, shall rise to take life’s crown.

Robert P. Ashe

|

We

sailed for Malta. My brother Robert and his wife and family were put

onto another ship, and they were taken to Cyprus. Oliver was in England

at the time. William had been at Hartlebury Grammar School, where our

cousin George Ashe was Headmaster. While we were in Smyrna, William

had left School and was working on a farm. My parents were expecting

him to arrive back in Smyrna about that time, and they were worried

that he might have left, and be on his way. Fortunately he had not yet

set off. Mary was with us in Malta, but we did not see much of her,

as she was madly in love with a tall dark Greek-Italian. He was a good

bit older than she was, and Father and Mother did not approve of the

friendship. I think their meetings were mostly secret, which of course

made it all the more exciting. It ended satisfactorily when we left

Malta, and went to Cartagena in Spain, where she married a water engineer

called Trevor Poore.

5 - Life as refugees

In Malta, we and the other refugees were put into the Lazaretto, a great barracks built by the Knights Templars as a staging post for their Crusades in the Holy Land. We were thankful to be alive and together as a family, but conditions were pretty primitive. Food was brought to us in buckets - the lunch always somewhat greasy, and then later in the day tea arrived in the same buckets with much of lunch’s grease floating on top. One day there was great excitement as there was rice for dinner. My sister noticed tiny black spots on some of the rice. On closer inspection they turned out to be the little black eyes of rice maggots.

Kind people in England sent clothes for the refugees, much of it astonishingly unsuitable - huge hats with flowers and feathers, long dresses of 1912 vintage, shoes with high heels and pointed toes. Father had some money in a bank in England and got some of it transferred. Mother went out and bought yards of blue serge, needles and cotton, and soon made a suit for Father, skirts for the girls, and a sailor suit for me. I never went out without the old pith helmet that came down over my ears. There were no games or toys, but Father’s sister, Aunt Florence who was with us, made a ball for me out of pieces of cork that floated in the harbour, and string which she wound round it. It had a fair bit of bounce, and I was greatly in demand amongst the other children if I would bring my ball.

Lord Plumer was Governor of Malta, and Father, as spokesman for the refugees had to meet him frequently. One day, Lord Plumer came to visit the refugees, and went into one of the rooms occupied by Fred Gout and his family. Fred was resting on his bed. He sat up and glared at his Lordship.

“Who are you?”

“I’m Lord Plumer.”

“Oh”, said Fred, “Are you a Britisher?”

Lord Plumer was put out.

“I tell you I’m Lord Plumer.”

Fred replied,

“Well, I’m Mr. Gout.”

The story went round with much mirth at the expense of Lord Plumer.

Most of the refugees had relatives in England, and little by little they dispersed. Father was appointed as Chaplain to the British community in Cartagena [info - postcard view], Spain. On our way there, we stopped in Rome, and my two sisters took me to visit the Vatican. We were stopped at the gate by two Vatican Guards who said we could not go in unless we had a letter from a priest. Ellen, forgetting about the celibacy of the Roman Catholic priesthood, said innocently,

“My father is a priest.”

The two guards nearly rolled on the floor with laughter, and we went away discomfited.

The British community in Cartagena was quite large, and most of the senior positions in the Arsenal were held by Scots with names like Malcolm, Buchanan, Carrick and Macgregor. William got a job in a silk-worm gut factory in Murcia making fishing lines. Mary married a mining engineer, Trevor Poore who worked for the Cartagena Water Company.

As my father was taking the Marriage Service, it fell to me, age 7, to give away the bride. All I can remember is stumbling over the hat-stand at the back of the Church with a bang that made everyone jump. I almost fell headlong to the floor, but fortunately I was firmly attached to Mary’s arm. The impetus of my stumble took us at high speed up the aisle, and we arrived breathless at the Altar steps.

Father was a great reader of the Latin and Greek classics, and he had been reading Livy’s account of Scipio’s capture of Cartagena. He told me how it had been done.

The city was built on a spit of land that protruded out into the bay. It was guarded on two sides by the sea, and on the west by a lagoon, so the Roman army was not able to surround it. The city was well-fortified by the Carthaginians, who repelled the first Roman attack. Scipio learnt from some fishermen that the lagoon was shallow, and could be forded, so while the main body of Romans attacked again along the spit, and the Carthaginians were busy engaging them, Scipio assembled five hundred men with scaling ladders on the edge of the lagoon. His men were guided across the shallows, reached the walls, and scaled them. The defenders were taken completely by surprise, thought it was a miracle, and Cartagena was captured.

With a guide who knew the way, you could still wade across the lagoon, but without a guide you would soon be out of your depth. Father used this story to point out to me the need for a Guide along life’s way.

How bewildering life can be without Jesus. One year in his speech to the nation, King George the Sixth quoted:

‘I said to the man who stood at the Gate of the Year: “Give me a light that I may tread safely into the unknown.”

And he replied: “Go out into the darkness, and put your hand into the hand of God. That shall be better than light, and safer than any known way.”’

I found the heat at mid-day intense. There are trees along the Muralla where we lived. When I had to go out at mid-day, I would pause in the shade of each tree, and walk slowly, then dart quickly into the shade of the next. In the evening men would come and water the masses of green succulents, planted in the Public Gardens, and damp down the dust, producing that sweet wet-earth smell.

Father used to visit any British ships that came into the harbour. Occasionally I went with him, and while he talked to the Captain, I was shown round by one of the officers. Once one asked me,

“Do you get the Daily Mail here?”

I had never heard of the Daily Mail newspaper and thought he meant, ‘did the postman bring letters every day’, so I said ‘yes’.

“When does it come?” he asked, and I replied,

“Every morning”.

He thought I was pulling his leg, and I can remember the sudden gleam in his eye, but I had no idea why he glared at me like that.

Every day I played with the boys in the street, and soon picked up Spanish.

I was known amongst them as ‘El Protestante’. One day a big boy caught me by the throat.

“Say you believe in the Virgin”, he demanded.

I was very frightened. “I don’t understand,” I said.

His grip tightened;

“Say you believe in the Virgin.”

I gasped out, “No comprendo.”

Some of my friends began to shout, “Let him go”, and he released me. I ran home, and told Father and Mother, and asked them what I should say.

Father said,

“Of course we believe in the Virgin. She was the mother of Jesus. If they ask you who his father was, say, ‘The Holy Spirit.’”

Some days after, the big boy caught me without my gang. He gripped me by the throat,

“Say you believe in the Virgin.”

“Of course I believe in the Virgin, she is the mother of Jesus.” I gasped. He was taken aback, and gave me a push that knocked me over. Religious honour was satisfied.

We used to have fearful fights with what we called the ‘beggar boys’ from the other part of the town. Our weapons were stones, which we used to great effect, sometimes beating them back, but at other times having to flee for our lives. I wore ‘alpargatas’, the rope-soled shoes that all the children wore, and a ‘babi’, a sort of cream coloured overall. I was soon indistinguishable from the rest of the gang, and could shout and swear in Spanish with the rest of them, and join their raiding parties.

In the evenings I would go with my friends, and sit on the wall of the Muralla watching the films on the open-air cinema screen. The only way to see them without paying was to sit behind the screen. Everything was the wrong way round but in those days there were always people who read the captions out loud. ‘Came the dawn’ would appear on the screen, and one would hear a murmur, ‘Came the dawn’. So we could follow what was going on. Our favourite actor was Tom Mix, known amongst us as ‘Tomaxin’.

My friends among the British were children I met at Sunday School. I fell deeply in love with one of the little girls aged 6, and I used to mope about on Sunday afternoons suffering from bad attacks of weekly love sickness. My more robust exertions playing football with the Spanish children soon cured me.

An incident took place about this time that had a profound effect on my character. Once, after a stormy session with my Father, I flew into a rage. He tried to calm me down, but I was angry and rebellious. He quoted a verse from the Prophet Jonah:

The Lord said,

“Doest thou well to be angry?”

Jonah replied peevishly,

“Yea, I do well to be angry, even unto death.?”

I stormed out, and went and hid under some prickly pear cactuses. I sat there: “Doest thou well to be angry, Pat?”

“Yea, I do well to be angry.”

It was as if God kept on saying to me,

“Doest thou well to angry?” until I said, “No, I don’t do well to be angry.”

After a considerable struggle, I plucked up courage and went to Father to apologise. I said,

“Father, I’m sorry.”

His reply was,

“Pat, you’re a gentleman.”

For me it was a discovery. Humility was not weakness. It needs strength to be humble.

6 - Return to Smyrna and on to England

After two years or so in Cartagena, we went back to Smyrna. Things had vastly changed. When we left Turkey in 1922, all the Turkish women were veiled, and all one could see of them when they were out in the streets was their eyes above the yashmak. Men all wore the red fez with a black tassel. When we returned, the veil had gone, and men were wearing every sort of hat imaginable, bowlers, homburgs, straws, anything but a fez. Kemal Ataturk had forbidden the yashmak and the fez. Ten leading men in Smyrna refused to obey, and he had them hanged from lampposts along the quay. People realised his orders were to be obeyed, and he plunged Turkey from a mediaeval oriental State, into a twentieth century Nation. The old writing from right to left was superseded by Roman characters, and the language was ‘purified’ - all foreign words eliminated. The old traditions of the Ottoman Empire had gone for ever.

All along the railway line between Boudja and Smyrna there were people camping out in shacks. They were the result of the ‘exchange of population’, a brilliant idea that caused untold misery. About one million Greeks from Turkey were exchanged for Moslems living in eastern Europe.

My parents took a lot of trouble teaching me Bible stories, and I read a chapter of the Bible every night before I went to sleep - in fact I found that I could not get to sleep without that nightly ritual. I once counted all the verses in the whole Bible, adding them up in vast columns chapter by chapter and book by book. I got heartily sick of it, but it made me doubtful about the value of quantity, and I have never wanted to start a sermon by saying that a word appears umpteen times in the Old Testament, as if the number made it more important. A key word like ‘Messiah’ appears only once in the Old Testament, and only twice in the New, so it is not the quantity that makes it important. We are a bit obsessed by ‘big is better’. It is not the amount of Bread and Wine one has at Holy Communion that has effect. It is the spirit in which it is taken that counts. We ‘take and eat by faith, with thanksgiving’. It does not seem to me to matter how much water one uses at Baptism. It is a sacrament that has a spiritual meaning, and whether you are dipped in whole, or have water poured on you, should not affect the spiritual result.

Father and Mother made a deep impression on me. What got across was not so much what they taught me, though I am eternally grateful for that, but the way they lived their lives. They were so natural - they never got pious or sanctimonious, or hypocritical. They showed amazing love and patience towards me, who could, at times be a horrid, rebellious brat, insolent and stubborn. Because Father was loving and patient and firm, I had no difficulty in finding God an even more loving, patient and firm Father. Mother was warm and gentle and long-suffering, and it was not difficult to transfer that to the ‘Motherhood’ of God.

5 - Life as refugees

In Malta, we and the other refugees were put into the Lazaretto, a great barracks built by the Knights Templars as a staging post for their Crusades in the Holy Land. We were thankful to be alive and together as a family, but conditions were pretty primitive. Food was brought to us in buckets - the lunch always somewhat greasy, and then later in the day tea arrived in the same buckets with much of lunch’s grease floating on top. One day there was great excitement as there was rice for dinner. My sister noticed tiny black spots on some of the rice. On closer inspection they turned out to be the little black eyes of rice maggots.

Kind people in England sent clothes for the refugees, much of it astonishingly unsuitable - huge hats with flowers and feathers, long dresses of 1912 vintage, shoes with high heels and pointed toes. Father had some money in a bank in England and got some of it transferred. Mother went out and bought yards of blue serge, needles and cotton, and soon made a suit for Father, skirts for the girls, and a sailor suit for me. I never went out without the old pith helmet that came down over my ears. There were no games or toys, but Father’s sister, Aunt Florence who was with us, made a ball for me out of pieces of cork that floated in the harbour, and string which she wound round it. It had a fair bit of bounce, and I was greatly in demand amongst the other children if I would bring my ball.

Lord Plumer was Governor of Malta, and Father, as spokesman for the refugees had to meet him frequently. One day, Lord Plumer came to visit the refugees, and went into one of the rooms occupied by Fred Gout and his family. Fred was resting on his bed. He sat up and glared at his Lordship.

“Who are you?”

“I’m Lord Plumer.”

“Oh”, said Fred, “Are you a Britisher?”

Lord Plumer was put out.

“I tell you I’m Lord Plumer.”

Fred replied,

“Well, I’m Mr. Gout.”

The story went round with much mirth at the expense of Lord Plumer.

Most of the refugees had relatives in England, and little by little they dispersed. Father was appointed as Chaplain to the British community in Cartagena [info - postcard view], Spain. On our way there, we stopped in Rome, and my two sisters took me to visit the Vatican. We were stopped at the gate by two Vatican Guards who said we could not go in unless we had a letter from a priest. Ellen, forgetting about the celibacy of the Roman Catholic priesthood, said innocently,

“My father is a priest.”

The two guards nearly rolled on the floor with laughter, and we went away discomfited.

The British community in Cartagena was quite large, and most of the senior positions in the Arsenal were held by Scots with names like Malcolm, Buchanan, Carrick and Macgregor. William got a job in a silk-worm gut factory in Murcia making fishing lines. Mary married a mining engineer, Trevor Poore who worked for the Cartagena Water Company.

As my father was taking the Marriage Service, it fell to me, age 7, to give away the bride. All I can remember is stumbling over the hat-stand at the back of the Church with a bang that made everyone jump. I almost fell headlong to the floor, but fortunately I was firmly attached to Mary’s arm. The impetus of my stumble took us at high speed up the aisle, and we arrived breathless at the Altar steps.

Father was a great reader of the Latin and Greek classics, and he had been reading Livy’s account of Scipio’s capture of Cartagena. He told me how it had been done.

The city was built on a spit of land that protruded out into the bay. It was guarded on two sides by the sea, and on the west by a lagoon, so the Roman army was not able to surround it. The city was well-fortified by the Carthaginians, who repelled the first Roman attack. Scipio learnt from some fishermen that the lagoon was shallow, and could be forded, so while the main body of Romans attacked again along the spit, and the Carthaginians were busy engaging them, Scipio assembled five hundred men with scaling ladders on the edge of the lagoon. His men were guided across the shallows, reached the walls, and scaled them. The defenders were taken completely by surprise, thought it was a miracle, and Cartagena was captured.

With a guide who knew the way, you could still wade across the lagoon, but without a guide you would soon be out of your depth. Father used this story to point out to me the need for a Guide along life’s way.

How bewildering life can be without Jesus. One year in his speech to the nation, King George the Sixth quoted:

‘I said to the man who stood at the Gate of the Year: “Give me a light that I may tread safely into the unknown.”

And he replied: “Go out into the darkness, and put your hand into the hand of God. That shall be better than light, and safer than any known way.”’