INTRODUCTION

The Sarells of Constantinople is an incomplete attempt to record in a manageable form the lives of the various members of the Sarell family and their first cousins. It is incomplete on two counts, firstly that no account is anything like a complete biography of the person concerned, and secondly that a number of members of the family do not get an account at all, because I have been unable to recover their story. Having said that, I hope that what is recorded is of interest to the reader, and that if on occasions it is repetitive from one account to another, I trust that you will bear with me in that each account is designed to stand alone.

The period covered is predominantly from the Napoleonic Wars to the First World War, although individual lives obviously predate this and continued beyond 1918. But the Sarell presence in Constantinople starts during the Napoleonic Wars with the arrival of James Sarell, and ends with the death of Helen Sarell in 1919. After the death of Helen, the Sarell family continued to have a property in Istanbul, which was only sold in 1960. Some of the Mavrogordato cousins continued to live in Istanbul into the 1930s, but by that time the family was not longer centred on Constantinople/Istanbul. Then of course in 1969 our branch of the family returned to Turkey when my father, Sir Roderick Sarell, was appointed as the British Ambassador to the Republic, and whilst it makes an interesting postscript to this story, it does not fall within the bounds of this account.

It is worth pointing out that the Sarell Family, prior to the move to Constantinople, had been an Exeter family for the previous two hundred and fifty years at least, but by the end of their time in Constantinople, the family was spread out from Britain, to Australia, South Africa, Cyprus, Greece, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Germany and Holland. Some were British subjects, others were nationals of these countries. In the First World War, a great-grand child of Richard Sarell would die for the British Empire in one arena of the war and for the Austro-Hungarian Empire in another arena. Evelyn Culling lamented the loss of the pre-war Europe describing it thus:

“Socially, for example, Europe was in a sense, one large family, with many houses. In London, Paris, Vienna, Rome – even Petersburg and Berlin – were social circles inter-allied by marriage, business, or friendship, and from capital to capital, from house to house, the members of those circles passed …. There was a cosmopolitan relationship which war, when it drew its iron rings round the nations, strangled instantly. The members of that European family found themselves in opposing camps and the war was to be to the death”

This account hopes to provide the reader with some understanding of the lives of the different members of the family through out this interesting period.

The information in this account comes from a variety of sources. Apart from documentary material, I have been able to rely on information and assistance from my father, Sir Roderick Sarell, my aunt Angela Cruickshank and Barbara Seabrook, the daughter of William Sarell, all of which has helped to provide a fuller picture of the Sarell family.

There is an amount of various documentary evidence that has been retained by the family over the years, such as baptism certificates, marriage certificates, and others obtained from the Public Record Office. There are various letters predominantly from Philip C. Sarell, but also to and from other members of the family which have been useful. Copies of various documents that have been acquired from the Ongley wings of the family and the Nugent wing of the Baltazzi branch, also helped to build up a picture of these branches of the family. In addition there are the unpublished diaries and journals of Henrietta Iwan Muller, which provide a first hand account of certain events pertaining to the family, the unpublished 1914 – 18 war journal of Ida Sarell, and the unpublished memoirs of May Wurmbrand.

There are, also, a number of published sources, such as the Foreign Office Lists, the Dominions Office and Colonial Office Lists, Who’s Who, the Commonwealth War Graves Lists, and Kelly’s Directories which have provided useful information. Furthermore the back copies of The Times have on occasions provided stories which were relevant. There are also some published books which are useful sources: Evelyn Culling wrote and published her autobiographical account of the First World War in 1932 under the title “Arms and the Woman”, a copy of which is held in the British Library; Heinrich Baltazzi-Scharschmid published an account in German of the Baltazzi family in Austria, called “Die Familien Baltazzi-Vetsera im Kaiserlichen Wien”. Unfortunately I do not read German and therefore it has not been as useful as it might have been in providing accounts of the Baltazzi family members. There are numerous books on the events surround the Mayerling Tragedy but the one that I have used was “Mayerling: the facts behind the Legend.” Because it provided information on the various members of the family, “A History of the Levant Company” by A.C.Wood provides the only account of the Company’s history, and even that is scant in regards to the relevant period. For later periods, “Storm Centres of the Near East 1879 – 1929” by Sir Robert Windham Graves KCMG, and “Life on the Bosphorus” by William J.J. Spry - segment - were both useful, as was “The Whittalls of Turkey 1809 -1973”. At a late stage David Barchard who is writing about Crete in the nineteenth century provided some useful information on Henry Sarell Ongley.

Finally I have spent a considerable amount of time on this project, and would like to thank my wife, Ange for being so supportive.

CJDS

December 2003

The Sarells of Constantinople is an incomplete attempt to record in a manageable form the lives of the various members of the Sarell family and their first cousins. It is incomplete on two counts, firstly that no account is anything like a complete biography of the person concerned, and secondly that a number of members of the family do not get an account at all, because I have been unable to recover their story. Having said that, I hope that what is recorded is of interest to the reader, and that if on occasions it is repetitive from one account to another, I trust that you will bear with me in that each account is designed to stand alone.

The period covered is predominantly from the Napoleonic Wars to the First World War, although individual lives obviously predate this and continued beyond 1918. But the Sarell presence in Constantinople starts during the Napoleonic Wars with the arrival of James Sarell, and ends with the death of Helen Sarell in 1919. After the death of Helen, the Sarell family continued to have a property in Istanbul, which was only sold in 1960. Some of the Mavrogordato cousins continued to live in Istanbul into the 1930s, but by that time the family was not longer centred on Constantinople/Istanbul. Then of course in 1969 our branch of the family returned to Turkey when my father, Sir Roderick Sarell, was appointed as the British Ambassador to the Republic, and whilst it makes an interesting postscript to this story, it does not fall within the bounds of this account.

It is worth pointing out that the Sarell Family, prior to the move to Constantinople, had been an Exeter family for the previous two hundred and fifty years at least, but by the end of their time in Constantinople, the family was spread out from Britain, to Australia, South Africa, Cyprus, Greece, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Germany and Holland. Some were British subjects, others were nationals of these countries. In the First World War, a great-grand child of Richard Sarell would die for the British Empire in one arena of the war and for the Austro-Hungarian Empire in another arena. Evelyn Culling lamented the loss of the pre-war Europe describing it thus:

“Socially, for example, Europe was in a sense, one large family, with many houses. In London, Paris, Vienna, Rome – even Petersburg and Berlin – were social circles inter-allied by marriage, business, or friendship, and from capital to capital, from house to house, the members of those circles passed …. There was a cosmopolitan relationship which war, when it drew its iron rings round the nations, strangled instantly. The members of that European family found themselves in opposing camps and the war was to be to the death”

This account hopes to provide the reader with some understanding of the lives of the different members of the family through out this interesting period.

The information in this account comes from a variety of sources. Apart from documentary material, I have been able to rely on information and assistance from my father, Sir Roderick Sarell, my aunt Angela Cruickshank and Barbara Seabrook, the daughter of William Sarell, all of which has helped to provide a fuller picture of the Sarell family.

There is an amount of various documentary evidence that has been retained by the family over the years, such as baptism certificates, marriage certificates, and others obtained from the Public Record Office. There are various letters predominantly from Philip C. Sarell, but also to and from other members of the family which have been useful. Copies of various documents that have been acquired from the Ongley wings of the family and the Nugent wing of the Baltazzi branch, also helped to build up a picture of these branches of the family. In addition there are the unpublished diaries and journals of Henrietta Iwan Muller, which provide a first hand account of certain events pertaining to the family, the unpublished 1914 – 18 war journal of Ida Sarell, and the unpublished memoirs of May Wurmbrand.

There are, also, a number of published sources, such as the Foreign Office Lists, the Dominions Office and Colonial Office Lists, Who’s Who, the Commonwealth War Graves Lists, and Kelly’s Directories which have provided useful information. Furthermore the back copies of The Times have on occasions provided stories which were relevant. There are also some published books which are useful sources: Evelyn Culling wrote and published her autobiographical account of the First World War in 1932 under the title “Arms and the Woman”, a copy of which is held in the British Library; Heinrich Baltazzi-Scharschmid published an account in German of the Baltazzi family in Austria, called “Die Familien Baltazzi-Vetsera im Kaiserlichen Wien”. Unfortunately I do not read German and therefore it has not been as useful as it might have been in providing accounts of the Baltazzi family members. There are numerous books on the events surround the Mayerling Tragedy but the one that I have used was “Mayerling: the facts behind the Legend.” Because it provided information on the various members of the family, “A History of the Levant Company” by A.C.Wood provides the only account of the Company’s history, and even that is scant in regards to the relevant period. For later periods, “Storm Centres of the Near East 1879 – 1929” by Sir Robert Windham Graves KCMG, and “Life on the Bosphorus” by William J.J. Spry - segment - were both useful, as was “The Whittalls of Turkey 1809 -1973”. At a late stage David Barchard who is writing about Crete in the nineteenth century provided some useful information on Henry Sarell Ongley.

Finally I have spent a considerable amount of time on this project, and would like to thank my wife, Ange for being so supportive.

CJDS

December 2003

SARAH

SARELL

Born 1758: Died 1817.

Sarah Sarell travelled out from England to Constantinople in 1810 to join her three sons who were merchants in the Levant Company. In so doing she became the most senior member of the Sarell family to be associated with Constantinople.

Sarah Sowton was born in Devon, and baptised at St Mary’s Major in Exeter on the 20th December, 1758. She grew up in Exeter, and on the 20th May 1781, she married Philip Sarell, a Fuller and Freeman of the City of Exeter, in the Sarell family’s Parish Church of St Mary’s Steps in Exeter. Her father, and her father-in-law, Richard Sarell were the witnesses to the marriage of Sarah to Philip.

Sarah and Philip had five children together. Their eldest child, James was baptised on the 5th May 1782 at the Church of St Thomas the Apostle. In 1784, their eldest daughter, Charlotte was baptised on the 4th June at the Church of St Mary Steps. Elizabeth was baptised on the 22nd October 1786, at St Thomas the Apostle, Richard on the 19th September 1791, at St Mary Steps, and the youngest son Philip in 1795. The family were living in the parish of St Mary Steps during this period, but St Mary Steps and the neighbouring parishes of St Edmunds, on the bridge and of St Thomas the Apostle on the west bank of the river seem to have been served by the clergy of St Thomas the Apostle. Certainly there was no incumbent solely at St Mary’s at this time.

In September 1796, Sarah’s younger daughter, Elizabeth, died and was buried from St Mary Steps, on the 7th of the month.

The wars with France were to have a devastating impact on the wool trade in Exeter, and this would have had an impact directly on the Sarell family since they were fullers and in the wool trade therefore. As a consequence of this, the traditional family career prospects for the three sons were closed. The family appears to have left Exeter between 1796 and 1803 as a consequence of this collapse in the wool trade.

The eldest son, James, was able to enter the Levant Company, and travelled out to Constantinople where in due course, he was sworn in as a freeman of the Company on the 15th July 1803. In due course he was joined by his brothers and then his mother, Sarah travelled out to join them in 1810.

Unfortunately, shortly after Sarah’s arrival in Constantinople, her eldest son died in 1811.

Sarah Sarell wrote the following letter which provides a good insight into her life in Constantinople.

“Constantinople March 13 1812.

Mr Joseph Brown. London,

Sir

The long period that has elapsed since my departure from England, and my not having written according to your polite request, is an omission for which I scarcely know how to apologise, but trust you will have the goodness not to impute either to inattention, or disrespect, what was occasioned only by the melancholy and unfortunate event, which so soon took place after I arrived in this country, and event which must cloud some part of every day of my future life with sorrow. I have however one consolation which is, that my beloved deceased son ever conducted himself prudently, so equitably towards all, with whom he had connexions, that he is universally spoken of, with respect and esteem. My now eldest son Rich’d who succeeded his brother, I believe, and trust you will find equally punctual and attentive to your interest, and to the interest of all his correspondents. My youngest Philip who left England a few months before myself, continues here, and promises to do very well, he is settled in the counting house with his Brother dependant on him for a few years, till time and experience may render him fit to conduct business. We all live very comfortably together, my children are dutiful and affectionate, and I should have been very happy had it pleased the Almighty to have spared my deceased son. Pardon me for relating so much of my own affairs. At present we live here in much security and peace and in many respects with as much comfort as in England, we have every luxury for the Table, much cheaper than in England, very fine poultry, the turkies the largest I ever saw, fish and fruit very fine, and plenty of good wine at a low price. The old English proverb is exactly verified here. That “God sends meat, but the Devil sends cooks,” for surely there never was in any christian country such miserable cooks, the women here have not the least ideas of doing anything in the kitchen, the cooks are all men, and for the most part Greeks from the islands, when I we first got into our House as I could only speak english, and the servants only Greek or a little Italian, we made some very droll mistakes at times. I now comprehend a little of both those languages, my son Rich’d speaks Greek like a native, also Italian and French pretty well. Philip has made some proficiency in Italian and is now learning French, and can make himself understood in Greek. The Turkish language is extremely difficult to acquire and very few learn it except those who are natives of the country. The whole appearance both of the people and the country, the variety of unusual sounds that salute ones ears, the extreme narrowness of the streets, the excessive dirt, the quantity of dogs, altogether make the place very disagreeable to a person, on arriving first from England, but a little time makes it familiar, and curiosity will find many subjects in a country and people formerly so famous in history. There are four distinct orders of persons who inhabit Constantinople, first and most numerous are the Turks who esteem themselves superior and Lords of all, the Greeks who as the original natives of the country, time immemorial before it was conquered by the descendants of Mahomet, are next to the Turks most numerous. These people in general hate and despise their Turkish Masters, yet as a conquered people they are obliged to submit, but they take every opportunity to vex the Turks when they can do it with impunity and those quarrels frequently end in the death of the poor Greek whom the Turk will surely murder if he is too much irritated. The Armenians come next under our observation those people are Christians, their ancestors were the peaceable inhabitants of the once flourishing kingdom or Armenia, which is situated about midway between the territories of the Grand Seignior and the Sultan of Persia. (Turkey and all Greece was at that time governed by the Greek Emperors,) Situated as those people were, between two such powerful neighbours, they alternatively fell a prey to both of them, but on their final subjugation and the extermination of their kingdom, thousands of the miserable exiles found an asylum in Constantinople under the government of the Greek Emperors, Since the conquest of this country by the Turks in 1443 the Armenians have gradually arisen to riches and oppulence (sic), they hold many places of confidence under the government, the coinage is wholly under their direction, as the mint is farmed out to them, their houses are most superb edifices built of stone, the gardens surrounded by high walls, within which they have fountains, statues and everything to please the eye and ear, those people when sequestered in their Houses indulge themselves in all the pride of dress, yellow boots decorate their feet, their long gowns of the finest silk, a pelisse lined in winter with fur which costs a thousand piastres a fine shawl tied around the waist, which costs from 50 to one hundred pounds sterling, the finest diamonds glitter on their fingers, and an immense calpack shelters their head. A Calpack is a covering for the head both of Greeks and Armenians, I do not know what tis manufactured of, but it is black, and sometimes black mixed with white very fine, but in shape exactly resembles an old fashioned copper boiler, whose brims being contracted much smaller than the other parts, imagine that you see one of those boilers become black and coated from smoke and placed on the head with the bottom upwards, and you will have an exact idea of this sort of hat, I should observe that the head is shaved all round the temples and behind, not a bit of hair to be seen only on the upper lip in the young, and an immense beard on the middle aged, and the old, the necks are quite exposed, as they never have a collar to the shirts.

The dress of the ladies is very little different from the men that is among the Turks, and Armenians, only that they are very careful of their hair and wear it immensely long flowing over the shoulders or braided in a number of little tresses. The Greek ladies have almost adopted the European dress, the usual employment of the females of this country is embroidery, and they execute it in the most beautiful style on muslin, with silk, gold or silver. I have two or three times been at Constantinople from which we are separated by the harbour I believe tis about a mile across, Constantinople is very much thronged with inhabitants, there are some very good houses, and the mosques make a very grand appearance, the chief thing that strikes the attention of a stranger is the bazaars, or market places, these are immense vaulted buildings of stone on each side of which are shops ranged regularly every profession has a bazar the first which I entered was the Egyptian Bazar, in that they sell every kind of drugs brought from Egypt besides colors for printing, rice, sugar, coffee and various articles in the same way, in that single market there are more than an hundred shops all exactly alike with a small room to sit in behind, as those who keep the shops are only in them during the day and return to their houses in the evening when the Bazar is shut, and secured with iron doors for fear of fire, besides those markets there are the Khans for the merchants of Persia, from India, from Barbary where all kinds of rich merchandize are deposited, and sold and in those the dealers remain during the time they remain in Constantinople. The Turks have some very beautiful manufactury in silk and cut velvets, their silk are very good and very well fancied. The velvets and silk and different colors wove in one piece and variegated in flowers and other figures, those velvets are mostly used for covering the cushions of sophas, a sopha is the great article of Turkish luxury, and very different from they are in England. A platform is raised round three sides of the room about a foot higher than the floor, and 3 feet in width from the wall, on this platform mattresses are placed all round and covered in summer with colord prints, trimmed with a deep fringe, at the back of the sofas against the wall, cushions, about a yard long are arranged, stuffed very hard with flax, in winter those cushions are covered with beautiful velvet and the mattresses with broad cloth or silk (I allude to the houses of the oppulent) in those sofas the Turks the Greeks and indeed all the people repose after dinner and take their pipe and coffee. Another singular custom of this country is the Tandour or fire table, this is a small table about the size of a breakfast table, besides the upper part it has a second table below a few inches from the floor in the midst of this is cut a round hole in which a pan containing a charcoal fire is placed, and over the table is a large blankett and quilt to keep in the heat, this table is placed in the angle between two sofas and round it the family and visitors sit in winter with their feet placed on the lower part and covered as much as they like with the coverings. This custom to a native of England has an odd appearance but becomes agreeable from use as very few of the houses have chimnies except in the kitchens, and the winters are very cold with much snow, but not long, four months is all that can be called winter. I have two or three times been in a boat up the Bosphorus or canal of the black sea the straight which parts Europe from Asia, tis not more than three miles wide at the widest part, and it is certainly not to be equalled for beauty of prospect in the world, on entering the boat you have the seraglio on your right whose fine buildings and woods rise gradually to the top of the hill The large city of Scutari is on the opposite side on the asiatic coast, and all the way for 14 miles tis a continuation of villages and towns on each side close to the mouth of the black sea, the grand seignior has some very beautiful houses on the banks of the canal, so lightly built and decorated with paintings and marble pillars that the outsides appear like some highly finished scene in the theatre, the canal in summer is covered with innumerable boats going and returning from the country houses of almost every description of people, and of parties who taking their provisions and servants make little excursions to the asiatic coast. And to increase the pleasure of the day they ascend some of the highest mountains in a kind of light waggon drawn by buffaloes, where it would be impossible for a horse to draw a carriage. These are some of the customs, and amusements of Constantinople but for all these things tis very dul here, and I hope Mrs Brown and all the family are in good health to whom please to make my respects, also to Mr Sculthorp. I remain Sir,

Your Obedient Servant S Sarell”

Sarah continued to live in Constantinople with her two sons, for the next five years. Her sons prospered with in the city and became important within the Levant Company Factory, in Constantinople.

On the 31st January 1817, Sarah Sarell died at 3.am. She was buried on the 1st February, at the “Grand Champs aux Morts”. The service was conducted by Cannon Thomas Shoolbred in the absence of a Protestant Minister.

In due course Sarah and her son James were re-interred at the Protestant cemetery at Ferikoy behind Pera, when the graves were removed from the “Grand Champs aux Mort”.

JAMES SARELL.

Born 1782: Died 1811.

James Sarell was the eldest child of Philip Sarell, Freeman of Exeter, and his wife Sarah. He was born in 1782, the year after Philip and Sarah had married, and was baptised on the 5th May at the Church of St Thomas the Apostle, which would suggest that the young family were living on the west side of the river in Exeter. However the parish of St Thomas the Apostle was providing the clergy for the parish of St Mary Steps on the east side of the river which is where the family were living. The two parishes and the parish of St Edmund being connected by the bridge across the Exe.

In due course, the family expanded as James was joined by two sister, Charlotte and Elizabeth, and then two younger brothers, Richard and Philip.

The family was severely effected by the wars with France at this time, and the collapse of the wool trade in Devon, meant that James and his brothers could no longer follow in their father’s footsteps and become fullers. At this time, another Exeter family, the Barings, who were also involved in the wool trade, had branched out into the London wool importing business and were also involved with the Levant Company. It is possible that through this link, the opening for James Sarell to go to Constantinople and join the Levant Company there, presented itself.

James travelled to Constantinople in the aftermath of Nelson’s victory over Napoleon at the Battle of Aboukir Bay, which resulted in the reopening of the Mediterranean to British trade. In Constantinople James joined the Levant Company, in April 1803 and on the 15th July of the same year, was sworn in as a Freeman of the Company.

James, at some point married a Greek woman called Imaragsa, by whom he had a son, Edward James Sarell, of whom there is no further record.

Four years after his arrival, James was involved in a famous and historic affair arising out of the conflicting pressures on Turkey of the French and the Russians. When Napoleon had invaded Egypt in 1798, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire, the Turks had responded with determination. The French Chargé d’Affaires and 2000 French residents were thrown into prison. But subsequently the Turkish attitude to France Britain and Russia had varied according to their progress and relative positions during the Napoleonic wars.

The route of the Austrians and Russians at Austerlitz, in 1805, enabled Napoleon to re-establish French influence at Constantinople. He sent General Sebastiani to encourage the Turks to confront the Russians, by removing the Hospodars of Moldavia and Wallachia. This was a breach of a decree of 1802, binding the Turks not to remove these officers within seven years of appointment. The Russians were furious, and when the British Ambassador, Arbuthnot, made clear the British Government’s support for the Russians demands, the Turskish authorities realised that this meant war. They prepared to seize the Ambassador, and the British Merchants and the Guardship as hostages. Arbuthnot had reliable information of this intended coup and on the pretext of a banquet on board HMS Endymion, which was the sole remaining British Man-of War in the Bosphorus, he assembled the Levant Company Merchants on board, and amongst their number was James Sarell.

Only the Captain and one merchant were in on the secret, and when night fell, the ship’s cables were cut, and she slipped away without warning to the Turks, passed the Dardanelles in safety and joined Admiral Duckworth’s squadron which had assembled of Tenedos. The Turks confiscated all British property and all British subjects were made prisoner. Arburthnot wrote to Sebastiani, the French representative, asking him to see that the Turks behaved to the women like a civilised power, and handed over British affairs to the Danish Minister Hubsch.

For the next two years Morier, the Consul General and the Levant Company merchants, including James Sarell, remained in Malta, without their wives and families. In April 1808, the Turkish government realising that the Franco-Russian pact at Tilsit, was aimed at the eventual partitioning of Turkey, wrote to Lord Collingwood, the Command-in- Chief of the Mediterranean fleet, offering to renew negotiations for peace. In September Robert Adair arrived at the Dardanelles. After three months of discussions, The Peace of the Dardanelles was signed in January 1809. It provided for the full restoration of the Capitulations and of the property of the merchants which had been sequestrated during the war.

The Levant Company merchants, including James Sarell, made claims for their losses which was the subject of somewhat caustic comments from London. A letter to them from London stated:

“We desire that you will communicate to Mr Barbour, Mr Prior, Mr Cartwright and Mr Sarell that we have given all due attention to their claims for reimbursement of the losses which they sustained in consequence of their having been brought from Constantinople by Mr Arbuthnot. On examining the statements of the gentlemen sworn to before you and on adding together the amount of the whole, we were much struck by their total discordance both in character and amount. The final statement of losses real and imaginary, including those of their correspondents, scarcely amounts to one half of the first claims which were declared to be for their own individual losses only and which they even desired us to lay before the House of Commons.”

James was joined by his two younger brothers in the Levant Company in Constantinople, after this incident. Richard was sworn in as a Freeman in 1811.

James’s mother Sarah, also joined him and his two brother in 1811, arriving a few months after the youngest son Philip. James, however, died very shortly after his mother’s arrival and was buried in the “Grand Champs aux Mort”. Subsequently he and his mother were re-interred at the Protestant cemetery at Ferikoy in the same grave.

Note: In June 2008 I visited this still visible grave and the inscription reads: “Sacred to the memory of James Sarell who departed this life on third of April 1811, Aged 29 years. – Also of Sarah Sarell, mother of the preceding, who died 31st January 1817. Aged 58 years.” - image of tomb.

James’ mother, in her letter of 13th March 1812 to Mr Joseph Brown, one of James’ correspondents, wrote:

“I have however one consolation which is, that my beloved deceased son ever conducted himself prudently, so equitably towards all, with whom he had connexions, that he is universally spoken of, with respect and esteem.”

After the death of James, it appears that the remaining family lost contact with his widow and son, Edward and apart from some correspondence from Imaragsa to London, nothing more is know of them.

RFGS &CJDS

CHARLOTTE ONGLEY / HARDY.

Born 1784: Died 1855.

Charlotte Sarell was the second child of Philip Sarell, Freeman of Exeter, and his wife Sarah. She was born in Exeter in 1874, and was baptised at St Mary Steps in Exeter on the 4th June 1784.

Her first husband was William Ongley, an officer in the Light Dragoons and with whom she had a son, Henry Sarell Ongley. William however died shortly after retiring from the army.

In 1821 on the 13th October, Charlotte remarried, having joined her brothers in Constantinople, where they were merchants with the Levant Company. Her second husband was Jonathan Hardy, who was also a merchant in the Levant Company.

The following year Richard, Charlotte’s brother was married to Euphrosyne Rhasi and Charlotte and her husband were the witnesses, in the British Embassy Chapel in Constantinople.

Charlotte, her husband and her son from her first marriage, continued to live in Constantinople alongside the family of her brother. But she and Jonathan had no children themselves.

In due course, her son left home to become the Consul at Crete, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire. He was appointed in 1837 to this position.

In 1841, Henry returns to Constantinople to marry Lucy, his cousin. Charlotte and Jonathan were witnesses at the wedding of her son, along with her brother Richard, who had to give his consent to the marriage as Lucy was only seventeen and therefore a minor.

Richard Sarell died in 1844 and Charlotte’s youngest brother, Philip had previously died at Smyrna in 1839, so that she was by now the eldest of the Sarell family in Constantinople.

Jonathan Hardy became the Vice-Consul Chancellor in Constantinople on the 4th June 1845, a post he would retain through out the rest of Charlotte’s life.

An indicator of the esteem that Charlotte and Jonathan Hardy were held in by their family, can be gauged from the names that her son and his wife gave their children, the eldest daughter was named Charlotte and the eldest son was named Henry Hardy Ongley.

Charlotte died in 1855 at Constantinople. Jonathan Hardy would outlive her by ten years.

He retired on the 7th February 1856, but continued to play an important role as the uncle to the children of Richard Sarell. He is recorded as being present at the wedding of Richard Sarell and Anna Maria Wilkin in 1857, at the wedding of Euphrosyne Sarell to James Crawford in 1862 and at the wedding of his great niece Helen Baltazzi to Albin Vetsera, in 1864. Jonathan Hardy was also remembered in Eliza Alison will in 1863, in which his niece left him five hundred pounds.

When Jonathan Hardy died on 2nd September 1866, Henrietta Iwan Muller recorded in her journal:

“I received a letter from Anna Maria, announcing to me the death of dear Mr Hardy, which has grieved me exceedingly as I was truly fond of the dear old gentleman and he of me.”

With the death of Jonathan Hardy the last link between the Levant Company and the Sarell family was broken.

Note: In June 2008 I visited the graves of Jonathan Hardy and Charlotte, curiously in separate cemeteries of Constantinople. In the Feriköy Protestant Cemetery the inscription on the grave of Jonathon Hardy reads: “Here rest remains of Jonathon Hardy Esq. Born Nov. 29 1785. Honoured as a Merchant of the Levant Company for his integrity. Respected as Vice Consul and Cancellier for his fidelity; beloved by his Countrymen and friends of other nations for his virtue, gentleness and pleasant wit. He departed this life in the faith of CHRIST Aug.14.1866.” - image of tomb. Similarly the inscription on the grave of Charlotte Hardy in the English Cemetery at Haydarpaşa reads: “Sacred to the Memory of Charlotte Hardy, Beloved and devoted wife of Jonathon Hardy Esq. HMB Vice Consul and Cancellier of this residence. Died 4th August 1855 Aged 71 years.” - image of tomb.

Born 1758: Died 1817.

Sarah Sarell travelled out from England to Constantinople in 1810 to join her three sons who were merchants in the Levant Company. In so doing she became the most senior member of the Sarell family to be associated with Constantinople.

Sarah Sowton was born in Devon, and baptised at St Mary’s Major in Exeter on the 20th December, 1758. She grew up in Exeter, and on the 20th May 1781, she married Philip Sarell, a Fuller and Freeman of the City of Exeter, in the Sarell family’s Parish Church of St Mary’s Steps in Exeter. Her father, and her father-in-law, Richard Sarell were the witnesses to the marriage of Sarah to Philip.

Sarah and Philip had five children together. Their eldest child, James was baptised on the 5th May 1782 at the Church of St Thomas the Apostle. In 1784, their eldest daughter, Charlotte was baptised on the 4th June at the Church of St Mary Steps. Elizabeth was baptised on the 22nd October 1786, at St Thomas the Apostle, Richard on the 19th September 1791, at St Mary Steps, and the youngest son Philip in 1795. The family were living in the parish of St Mary Steps during this period, but St Mary Steps and the neighbouring parishes of St Edmunds, on the bridge and of St Thomas the Apostle on the west bank of the river seem to have been served by the clergy of St Thomas the Apostle. Certainly there was no incumbent solely at St Mary’s at this time.

In September 1796, Sarah’s younger daughter, Elizabeth, died and was buried from St Mary Steps, on the 7th of the month.

The wars with France were to have a devastating impact on the wool trade in Exeter, and this would have had an impact directly on the Sarell family since they were fullers and in the wool trade therefore. As a consequence of this, the traditional family career prospects for the three sons were closed. The family appears to have left Exeter between 1796 and 1803 as a consequence of this collapse in the wool trade.

The eldest son, James, was able to enter the Levant Company, and travelled out to Constantinople where in due course, he was sworn in as a freeman of the Company on the 15th July 1803. In due course he was joined by his brothers and then his mother, Sarah travelled out to join them in 1810.

Unfortunately, shortly after Sarah’s arrival in Constantinople, her eldest son died in 1811.

Sarah Sarell wrote the following letter which provides a good insight into her life in Constantinople.

“Constantinople March 13 1812.

Mr Joseph Brown. London,

Sir

The long period that has elapsed since my departure from England, and my not having written according to your polite request, is an omission for which I scarcely know how to apologise, but trust you will have the goodness not to impute either to inattention, or disrespect, what was occasioned only by the melancholy and unfortunate event, which so soon took place after I arrived in this country, and event which must cloud some part of every day of my future life with sorrow. I have however one consolation which is, that my beloved deceased son ever conducted himself prudently, so equitably towards all, with whom he had connexions, that he is universally spoken of, with respect and esteem. My now eldest son Rich’d who succeeded his brother, I believe, and trust you will find equally punctual and attentive to your interest, and to the interest of all his correspondents. My youngest Philip who left England a few months before myself, continues here, and promises to do very well, he is settled in the counting house with his Brother dependant on him for a few years, till time and experience may render him fit to conduct business. We all live very comfortably together, my children are dutiful and affectionate, and I should have been very happy had it pleased the Almighty to have spared my deceased son. Pardon me for relating so much of my own affairs. At present we live here in much security and peace and in many respects with as much comfort as in England, we have every luxury for the Table, much cheaper than in England, very fine poultry, the turkies the largest I ever saw, fish and fruit very fine, and plenty of good wine at a low price. The old English proverb is exactly verified here. That “God sends meat, but the Devil sends cooks,” for surely there never was in any christian country such miserable cooks, the women here have not the least ideas of doing anything in the kitchen, the cooks are all men, and for the most part Greeks from the islands, when I we first got into our House as I could only speak english, and the servants only Greek or a little Italian, we made some very droll mistakes at times. I now comprehend a little of both those languages, my son Rich’d speaks Greek like a native, also Italian and French pretty well. Philip has made some proficiency in Italian and is now learning French, and can make himself understood in Greek. The Turkish language is extremely difficult to acquire and very few learn it except those who are natives of the country. The whole appearance both of the people and the country, the variety of unusual sounds that salute ones ears, the extreme narrowness of the streets, the excessive dirt, the quantity of dogs, altogether make the place very disagreeable to a person, on arriving first from England, but a little time makes it familiar, and curiosity will find many subjects in a country and people formerly so famous in history. There are four distinct orders of persons who inhabit Constantinople, first and most numerous are the Turks who esteem themselves superior and Lords of all, the Greeks who as the original natives of the country, time immemorial before it was conquered by the descendants of Mahomet, are next to the Turks most numerous. These people in general hate and despise their Turkish Masters, yet as a conquered people they are obliged to submit, but they take every opportunity to vex the Turks when they can do it with impunity and those quarrels frequently end in the death of the poor Greek whom the Turk will surely murder if he is too much irritated. The Armenians come next under our observation those people are Christians, their ancestors were the peaceable inhabitants of the once flourishing kingdom or Armenia, which is situated about midway between the territories of the Grand Seignior and the Sultan of Persia. (Turkey and all Greece was at that time governed by the Greek Emperors,) Situated as those people were, between two such powerful neighbours, they alternatively fell a prey to both of them, but on their final subjugation and the extermination of their kingdom, thousands of the miserable exiles found an asylum in Constantinople under the government of the Greek Emperors, Since the conquest of this country by the Turks in 1443 the Armenians have gradually arisen to riches and oppulence (sic), they hold many places of confidence under the government, the coinage is wholly under their direction, as the mint is farmed out to them, their houses are most superb edifices built of stone, the gardens surrounded by high walls, within which they have fountains, statues and everything to please the eye and ear, those people when sequestered in their Houses indulge themselves in all the pride of dress, yellow boots decorate their feet, their long gowns of the finest silk, a pelisse lined in winter with fur which costs a thousand piastres a fine shawl tied around the waist, which costs from 50 to one hundred pounds sterling, the finest diamonds glitter on their fingers, and an immense calpack shelters their head. A Calpack is a covering for the head both of Greeks and Armenians, I do not know what tis manufactured of, but it is black, and sometimes black mixed with white very fine, but in shape exactly resembles an old fashioned copper boiler, whose brims being contracted much smaller than the other parts, imagine that you see one of those boilers become black and coated from smoke and placed on the head with the bottom upwards, and you will have an exact idea of this sort of hat, I should observe that the head is shaved all round the temples and behind, not a bit of hair to be seen only on the upper lip in the young, and an immense beard on the middle aged, and the old, the necks are quite exposed, as they never have a collar to the shirts.

The dress of the ladies is very little different from the men that is among the Turks, and Armenians, only that they are very careful of their hair and wear it immensely long flowing over the shoulders or braided in a number of little tresses. The Greek ladies have almost adopted the European dress, the usual employment of the females of this country is embroidery, and they execute it in the most beautiful style on muslin, with silk, gold or silver. I have two or three times been at Constantinople from which we are separated by the harbour I believe tis about a mile across, Constantinople is very much thronged with inhabitants, there are some very good houses, and the mosques make a very grand appearance, the chief thing that strikes the attention of a stranger is the bazaars, or market places, these are immense vaulted buildings of stone on each side of which are shops ranged regularly every profession has a bazar the first which I entered was the Egyptian Bazar, in that they sell every kind of drugs brought from Egypt besides colors for printing, rice, sugar, coffee and various articles in the same way, in that single market there are more than an hundred shops all exactly alike with a small room to sit in behind, as those who keep the shops are only in them during the day and return to their houses in the evening when the Bazar is shut, and secured with iron doors for fear of fire, besides those markets there are the Khans for the merchants of Persia, from India, from Barbary where all kinds of rich merchandize are deposited, and sold and in those the dealers remain during the time they remain in Constantinople. The Turks have some very beautiful manufactury in silk and cut velvets, their silk are very good and very well fancied. The velvets and silk and different colors wove in one piece and variegated in flowers and other figures, those velvets are mostly used for covering the cushions of sophas, a sopha is the great article of Turkish luxury, and very different from they are in England. A platform is raised round three sides of the room about a foot higher than the floor, and 3 feet in width from the wall, on this platform mattresses are placed all round and covered in summer with colord prints, trimmed with a deep fringe, at the back of the sofas against the wall, cushions, about a yard long are arranged, stuffed very hard with flax, in winter those cushions are covered with beautiful velvet and the mattresses with broad cloth or silk (I allude to the houses of the oppulent) in those sofas the Turks the Greeks and indeed all the people repose after dinner and take their pipe and coffee. Another singular custom of this country is the Tandour or fire table, this is a small table about the size of a breakfast table, besides the upper part it has a second table below a few inches from the floor in the midst of this is cut a round hole in which a pan containing a charcoal fire is placed, and over the table is a large blankett and quilt to keep in the heat, this table is placed in the angle between two sofas and round it the family and visitors sit in winter with their feet placed on the lower part and covered as much as they like with the coverings. This custom to a native of England has an odd appearance but becomes agreeable from use as very few of the houses have chimnies except in the kitchens, and the winters are very cold with much snow, but not long, four months is all that can be called winter. I have two or three times been in a boat up the Bosphorus or canal of the black sea the straight which parts Europe from Asia, tis not more than three miles wide at the widest part, and it is certainly not to be equalled for beauty of prospect in the world, on entering the boat you have the seraglio on your right whose fine buildings and woods rise gradually to the top of the hill The large city of Scutari is on the opposite side on the asiatic coast, and all the way for 14 miles tis a continuation of villages and towns on each side close to the mouth of the black sea, the grand seignior has some very beautiful houses on the banks of the canal, so lightly built and decorated with paintings and marble pillars that the outsides appear like some highly finished scene in the theatre, the canal in summer is covered with innumerable boats going and returning from the country houses of almost every description of people, and of parties who taking their provisions and servants make little excursions to the asiatic coast. And to increase the pleasure of the day they ascend some of the highest mountains in a kind of light waggon drawn by buffaloes, where it would be impossible for a horse to draw a carriage. These are some of the customs, and amusements of Constantinople but for all these things tis very dul here, and I hope Mrs Brown and all the family are in good health to whom please to make my respects, also to Mr Sculthorp. I remain Sir,

Your Obedient Servant S Sarell”

Sarah continued to live in Constantinople with her two sons, for the next five years. Her sons prospered with in the city and became important within the Levant Company Factory, in Constantinople.

On the 31st January 1817, Sarah Sarell died at 3.am. She was buried on the 1st February, at the “Grand Champs aux Morts”. The service was conducted by Cannon Thomas Shoolbred in the absence of a Protestant Minister.

In due course Sarah and her son James were re-interred at the Protestant cemetery at Ferikoy behind Pera, when the graves were removed from the “Grand Champs aux Mort”.

JAMES SARELL.

Born 1782: Died 1811.

James Sarell was the eldest child of Philip Sarell, Freeman of Exeter, and his wife Sarah. He was born in 1782, the year after Philip and Sarah had married, and was baptised on the 5th May at the Church of St Thomas the Apostle, which would suggest that the young family were living on the west side of the river in Exeter. However the parish of St Thomas the Apostle was providing the clergy for the parish of St Mary Steps on the east side of the river which is where the family were living. The two parishes and the parish of St Edmund being connected by the bridge across the Exe.

In due course, the family expanded as James was joined by two sister, Charlotte and Elizabeth, and then two younger brothers, Richard and Philip.

The family was severely effected by the wars with France at this time, and the collapse of the wool trade in Devon, meant that James and his brothers could no longer follow in their father’s footsteps and become fullers. At this time, another Exeter family, the Barings, who were also involved in the wool trade, had branched out into the London wool importing business and were also involved with the Levant Company. It is possible that through this link, the opening for James Sarell to go to Constantinople and join the Levant Company there, presented itself.

James travelled to Constantinople in the aftermath of Nelson’s victory over Napoleon at the Battle of Aboukir Bay, which resulted in the reopening of the Mediterranean to British trade. In Constantinople James joined the Levant Company, in April 1803 and on the 15th July of the same year, was sworn in as a Freeman of the Company.

James, at some point married a Greek woman called Imaragsa, by whom he had a son, Edward James Sarell, of whom there is no further record.

Four years after his arrival, James was involved in a famous and historic affair arising out of the conflicting pressures on Turkey of the French and the Russians. When Napoleon had invaded Egypt in 1798, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire, the Turks had responded with determination. The French Chargé d’Affaires and 2000 French residents were thrown into prison. But subsequently the Turkish attitude to France Britain and Russia had varied according to their progress and relative positions during the Napoleonic wars.

The route of the Austrians and Russians at Austerlitz, in 1805, enabled Napoleon to re-establish French influence at Constantinople. He sent General Sebastiani to encourage the Turks to confront the Russians, by removing the Hospodars of Moldavia and Wallachia. This was a breach of a decree of 1802, binding the Turks not to remove these officers within seven years of appointment. The Russians were furious, and when the British Ambassador, Arbuthnot, made clear the British Government’s support for the Russians demands, the Turskish authorities realised that this meant war. They prepared to seize the Ambassador, and the British Merchants and the Guardship as hostages. Arbuthnot had reliable information of this intended coup and on the pretext of a banquet on board HMS Endymion, which was the sole remaining British Man-of War in the Bosphorus, he assembled the Levant Company Merchants on board, and amongst their number was James Sarell.

Only the Captain and one merchant were in on the secret, and when night fell, the ship’s cables were cut, and she slipped away without warning to the Turks, passed the Dardanelles in safety and joined Admiral Duckworth’s squadron which had assembled of Tenedos. The Turks confiscated all British property and all British subjects were made prisoner. Arburthnot wrote to Sebastiani, the French representative, asking him to see that the Turks behaved to the women like a civilised power, and handed over British affairs to the Danish Minister Hubsch.

For the next two years Morier, the Consul General and the Levant Company merchants, including James Sarell, remained in Malta, without their wives and families. In April 1808, the Turkish government realising that the Franco-Russian pact at Tilsit, was aimed at the eventual partitioning of Turkey, wrote to Lord Collingwood, the Command-in- Chief of the Mediterranean fleet, offering to renew negotiations for peace. In September Robert Adair arrived at the Dardanelles. After three months of discussions, The Peace of the Dardanelles was signed in January 1809. It provided for the full restoration of the Capitulations and of the property of the merchants which had been sequestrated during the war.

The Levant Company merchants, including James Sarell, made claims for their losses which was the subject of somewhat caustic comments from London. A letter to them from London stated:

“We desire that you will communicate to Mr Barbour, Mr Prior, Mr Cartwright and Mr Sarell that we have given all due attention to their claims for reimbursement of the losses which they sustained in consequence of their having been brought from Constantinople by Mr Arbuthnot. On examining the statements of the gentlemen sworn to before you and on adding together the amount of the whole, we were much struck by their total discordance both in character and amount. The final statement of losses real and imaginary, including those of their correspondents, scarcely amounts to one half of the first claims which were declared to be for their own individual losses only and which they even desired us to lay before the House of Commons.”

James was joined by his two younger brothers in the Levant Company in Constantinople, after this incident. Richard was sworn in as a Freeman in 1811.

James’s mother Sarah, also joined him and his two brother in 1811, arriving a few months after the youngest son Philip. James, however, died very shortly after his mother’s arrival and was buried in the “Grand Champs aux Mort”. Subsequently he and his mother were re-interred at the Protestant cemetery at Ferikoy in the same grave.

Note: In June 2008 I visited this still visible grave and the inscription reads: “Sacred to the memory of James Sarell who departed this life on third of April 1811, Aged 29 years. – Also of Sarah Sarell, mother of the preceding, who died 31st January 1817. Aged 58 years.” - image of tomb.

James’ mother, in her letter of 13th March 1812 to Mr Joseph Brown, one of James’ correspondents, wrote:

“I have however one consolation which is, that my beloved deceased son ever conducted himself prudently, so equitably towards all, with whom he had connexions, that he is universally spoken of, with respect and esteem.”

After the death of James, it appears that the remaining family lost contact with his widow and son, Edward and apart from some correspondence from Imaragsa to London, nothing more is know of them.

RFGS &CJDS

CHARLOTTE ONGLEY / HARDY.

Born 1784: Died 1855.

Charlotte Sarell was the second child of Philip Sarell, Freeman of Exeter, and his wife Sarah. She was born in Exeter in 1874, and was baptised at St Mary Steps in Exeter on the 4th June 1784.

Her first husband was William Ongley, an officer in the Light Dragoons and with whom she had a son, Henry Sarell Ongley. William however died shortly after retiring from the army.

In 1821 on the 13th October, Charlotte remarried, having joined her brothers in Constantinople, where they were merchants with the Levant Company. Her second husband was Jonathan Hardy, who was also a merchant in the Levant Company.

The following year Richard, Charlotte’s brother was married to Euphrosyne Rhasi and Charlotte and her husband were the witnesses, in the British Embassy Chapel in Constantinople.

Charlotte, her husband and her son from her first marriage, continued to live in Constantinople alongside the family of her brother. But she and Jonathan had no children themselves.

In due course, her son left home to become the Consul at Crete, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire. He was appointed in 1837 to this position.

In 1841, Henry returns to Constantinople to marry Lucy, his cousin. Charlotte and Jonathan were witnesses at the wedding of her son, along with her brother Richard, who had to give his consent to the marriage as Lucy was only seventeen and therefore a minor.

Richard Sarell died in 1844 and Charlotte’s youngest brother, Philip had previously died at Smyrna in 1839, so that she was by now the eldest of the Sarell family in Constantinople.

Jonathan Hardy became the Vice-Consul Chancellor in Constantinople on the 4th June 1845, a post he would retain through out the rest of Charlotte’s life.

An indicator of the esteem that Charlotte and Jonathan Hardy were held in by their family, can be gauged from the names that her son and his wife gave their children, the eldest daughter was named Charlotte and the eldest son was named Henry Hardy Ongley.

Charlotte died in 1855 at Constantinople. Jonathan Hardy would outlive her by ten years.

He retired on the 7th February 1856, but continued to play an important role as the uncle to the children of Richard Sarell. He is recorded as being present at the wedding of Richard Sarell and Anna Maria Wilkin in 1857, at the wedding of Euphrosyne Sarell to James Crawford in 1862 and at the wedding of his great niece Helen Baltazzi to Albin Vetsera, in 1864. Jonathan Hardy was also remembered in Eliza Alison will in 1863, in which his niece left him five hundred pounds.

When Jonathan Hardy died on 2nd September 1866, Henrietta Iwan Muller recorded in her journal:

“I received a letter from Anna Maria, announcing to me the death of dear Mr Hardy, which has grieved me exceedingly as I was truly fond of the dear old gentleman and he of me.”

With the death of Jonathan Hardy the last link between the Levant Company and the Sarell family was broken.

Note: In June 2008 I visited the graves of Jonathan Hardy and Charlotte, curiously in separate cemeteries of Constantinople. In the Feriköy Protestant Cemetery the inscription on the grave of Jonathon Hardy reads: “Here rest remains of Jonathon Hardy Esq. Born Nov. 29 1785. Honoured as a Merchant of the Levant Company for his integrity. Respected as Vice Consul and Cancellier for his fidelity; beloved by his Countrymen and friends of other nations for his virtue, gentleness and pleasant wit. He departed this life in the faith of CHRIST Aug.14.1866.” - image of tomb. Similarly the inscription on the grave of Charlotte Hardy in the English Cemetery at Haydarpaşa reads: “Sacred to the Memory of Charlotte Hardy, Beloved and devoted wife of Jonathon Hardy Esq. HMB Vice Consul and Cancellier of this residence. Died 4th August 1855 Aged 71 years.” - image of tomb.

RICHARD

SARELL.

Born 1791: Died 1844.

Richard Sarell was the second son and fourth child, of Philip Sarell, Freeman of Exeter and his wife Sarah. He was born in Exeter and baptised at St Mary Steps on the 19th September 1791.

The economic effects of the wars with France, resulted in the wool trade in Devon collapsing, and since Philip Sarell, Richard’s father was a fuller, involved in the production of cloth, the impact was severe on the family. Richard’s eldest brother, James, travelled to Constantinople and was sworn in as a Freeman of the Levant Company there, in 1803 and when Richard was older enough, he followed his brother to Constantinople.

In 1811, Richard was sworn in as a Freeman of the Levant Company, at Constantinople. Philip, his younger brother was now working alongside him. But his elder brother James died in the same year, shortly after their mother Sarah had joined her sons in Constantinople.

A colleague in the Levant Company Factory in Constantinople, left the city towards the end of 1811, and entrusted his affairs to Richard. A clear demonstration of the respect, that Richard had gained in a short space of time, in the Factory.

Richard lived with his mother and brother together in Constantinople, and became fluent in the various languages necessary for the conduct of business in the city, namely Greek, French and Italian.

Born 1791: Died 1844.

Richard Sarell was the second son and fourth child, of Philip Sarell, Freeman of Exeter and his wife Sarah. He was born in Exeter and baptised at St Mary Steps on the 19th September 1791.

The economic effects of the wars with France, resulted in the wool trade in Devon collapsing, and since Philip Sarell, Richard’s father was a fuller, involved in the production of cloth, the impact was severe on the family. Richard’s eldest brother, James, travelled to Constantinople and was sworn in as a Freeman of the Levant Company there, in 1803 and when Richard was older enough, he followed his brother to Constantinople.

In 1811, Richard was sworn in as a Freeman of the Levant Company, at Constantinople. Philip, his younger brother was now working alongside him. But his elder brother James died in the same year, shortly after their mother Sarah had joined her sons in Constantinople.

A colleague in the Levant Company Factory in Constantinople, left the city towards the end of 1811, and entrusted his affairs to Richard. A clear demonstration of the respect, that Richard had gained in a short space of time, in the Factory.

Richard lived with his mother and brother together in Constantinople, and became fluent in the various languages necessary for the conduct of business in the city, namely Greek, French and Italian.

|

In June 1819, the Levant Company Factory in Constantinople was having problems with the Ottoman Authorities who were imposing a double duty on made mocha coffee on the merchants. Also a consignment of iron belonging to the British merchants, had been impounded in an attempt to force the merchants to pay the increased tariff. The Levant Company Factory approached the British Ambassador, Sir Robert Liston, for assistance in these matters. The Ambassador was not hopeful of a speedy resolution to the problems, and was not prepared to go to the lengths that the Factory members were requesting. However he did disclose that the British Government had authorised him to seek a revision of the various tariffs and that he was entering into negotiations on this matter, and would resolve the outstanding issue of the iron as part of these negotiations.

In 1821 It was against this backdrop that the Levant Company made Richard the treasurer of the Constantinople Factory. It was a significant position within the Company, and indicative of his standing amongst his fellow British merchants. He took over the position from his predecessor Mr T.Black, on the 30th June 1819, after the accounts had been examined by two other members of the Factory, Mr Wright and Mr Ray.

Richard had, in due course married, but his first wife died leaving him a widower. But on the 15th April 1822, Easter Morning, Richard married his second wife, Euphrosyne Rhasi the daughter of the late Demetrius Rhasi. His two witnesses were his sister Charlotte and his brother-in-law and fellow member of the Levant Company, Jonathan Hardy.

The following year Elizabeth the first of Richard’s children was born and was named after his eldest sister. On the 25th May, 1824, Lucy his second daughter was born, and she was in due course be followed two brothers and five sisters.

In 1825, the Levant Company was wound up, but Richard and his family, his brother, and his brother-in-law and sister continued to live in and work in Constantinople and would remain significant members of the British Community.

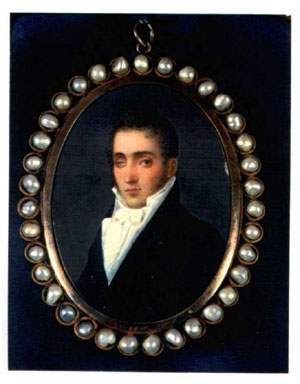

In 1827, the British Embassy was withdrawn from Constantinople, after the battle at Navarino. Sir Stratford Canning entrusted Richard Sarell with looking after the British commercial during the absence of the Embassy. Over the next three years until the restoration of diplomatic relations in 1831, Richard was the Chargé d’Affaires in Constantinople. In recognition of his difficult role during that period, he was presented with a gold snuff box with a portrait of King William IV on it. A letter from Sir Robert Gordon at the Foreign Office accompanied the gold snuff box, to the Ambassador stating:

“Sir,

I have great pleasure in transmitting to Your Excellency, by His Majesty’s command, the accompanying Gold Box, with His Majesty’s Portrait, to be presented to Mr Sarell, as a Testimonial of his Majesty’s gracious approbation of the services which Your Excellency has reported Mr Sarell to have rendered to the interests of His Majesty’s trading Subjects during the absence of the British Embassy from Constantinople.”

Richard Sarell was subsequently appointed to the post of Vice-Consul at Constantinople.

In the aftermath of this period, Richard’s family continued to grow. Eliza as Elizabeth was know, and Lucy, had been joined by Philip James, in 1825, Charlotte in 1826, and Richard in 1829. Now Euphrosyne was born in 1831, followed by Alice Fanny in 1835, Harriet in 1835 and finally Helen in 1836.

Richard’s second daughter Lucy married her cousin Henry Sarell Ongley in 1841, and then Eliza married Theodore Baltazzi in 1842. This second marriage is indicative of the standing of Richard and his family, in Constantinople as Theodore Baltazzi was the richest banker in Constantinople, and was the banker to the Sultan.

On the 18th February 1844, whilst on a trip to London, Richard died from a diseased heart. He was staying at 42 Gower Place. His death was announced in the Times.

Back in Constantinople, Richard’s widow Euphrosyne continued to bring up their children, with assistance from her daughter Eliza and her husband, and also from her brother-in-law Jonathan Hardy. In later life Helen, the youngest daughter lived with Euphrosyne, as her companion, in their house in Büyükdere [half way up the Bosphorus coast].

Euphrosyne eventually died in 1884 at the age of 85, and was buried according to the rites of the Greek Orthodox Church.

PHILIP SARELL

Born 1795: Died 1839.

Philip Sarell was the youngest child of Philip Sarell, freeman of Exeter and his wife Sarah. He was born in Exeter in 1795, the youngest of five, when the family were living in the parish of St Mary Steps, by the river Exe and in the hub of the commercial heart of the city.

By the time Philip was born, the impact of the war with France, was resulting in a collapse of the local Devonshire wool trade. His father was a fuller and therefore the impact must have been severe. It appears that the family left Exeter shortly after Philip was born. His eldest brother James travelled to Constantinople in the early years of the nineteenth century and was sworn in as a freeman at the factory in Constantinople in 1803. Philip followed James and his other brother, Richard out to Constantinople and was in turn followed by his mother shortly afterwards and then by his sister in due course.

In Constantinople, his brother James, died shortly after Philip’s arrival. Philip however entered the Levant Company factory where Richard was by now a freeman himself. Philip in due course also became a freeman of the company and a successful merchant, having learnt various of the languages necessary for commerce, such as Greek, Italian and French.

In 1825 the Levant Company was wound up, but Philip along with other members of the Sarell family continued to live and prosper in the Ottoman Empire. Philip and his brother Richard are recorded as bankers handling accounts for clients of Coutts who were in the Ottoman Empire at this time. But whilst Richard remained predominantly in Constantinople, Philip appears to have moved to Smyrna at some point, Smyrna being the other major trading port with British trade in the heart of the Ottoman Empire. Smyrna had a sizeable British Community at this time. The Whittall family had been there since 1809, and there were others such as the La Fontaine family, the Maltass family and the Wilkin family, all of who would rub shoulders with the Sarell family over years. The Community lived outside the city in the village of Bournabat, and within Smyrna in the district between the amin street and the harbours edge.

It was in Smyrna, in 1839, that Philip passed away, being survived by his brother Richard and his sister Charlotte.

ELIZABETH

BALTAZZI / ALISON.

Born 1823: Died 1863.

Elizabeth Sarell was the oldest child of Richard Sarell, a Levant Company merchant and his second wife Euphrosyne Rhasi. She was born in Constantinople in 1823 and grew up there. She was known by the abbreviated form of her name: Eliza.

On the 5th February 1842, Eliza married Theodore Baltazzi, who was twenty-five years her senior. As Eliza had not yet reached the age of twenty-one, she required the consent of her father to marry, and although Theodore Baltazzi was considerably older, he was also a very successful banker and Richard gave his consent to the marriage. The marriage took place in the Chapel of the Her Majesty’s Ambassador to the Sublime Porte, and was witnessed by amongst others, her two younger brothers Philip and Richard.

Almost immediately after her marriage, Eliza became pregnant, and her first child was born on the 16th December 1842 in Constantinople, and subsequently baptised at the Ambassador’s Chapel, on the 29th.

Theodore Baltazzi was at the time of his marriage, a subject of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, following the ceding of Venice to the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1815. This was because prior to this, the family had in the previous century managed to become

Born 1823: Died 1863.

Elizabeth Sarell was the oldest child of Richard Sarell, a Levant Company merchant and his second wife Euphrosyne Rhasi. She was born in Constantinople in 1823 and grew up there. She was known by the abbreviated form of her name: Eliza.

On the 5th February 1842, Eliza married Theodore Baltazzi, who was twenty-five years her senior. As Eliza had not yet reached the age of twenty-one, she required the consent of her father to marry, and although Theodore Baltazzi was considerably older, he was also a very successful banker and Richard gave his consent to the marriage. The marriage took place in the Chapel of the Her Majesty’s Ambassador to the Sublime Porte, and was witnessed by amongst others, her two younger brothers Philip and Richard.

Almost immediately after her marriage, Eliza became pregnant, and her first child was born on the 16th December 1842 in Constantinople, and subsequently baptised at the Ambassador’s Chapel, on the 29th.

Theodore Baltazzi was at the time of his marriage, a subject of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, following the ceding of Venice to the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1815. This was because prior to this, the family had in the previous century managed to become

|

citizen

of the Republic of Venice, an important safeguard for successful Christians

in the Ottoman Empire.

Theodore had trained as a banker in Paris, and had returned to Constantinople, where he had entered his father’s bank. In due course he became banker to the Sultan himself and became the richest person in Constantinople.

Apart from the properties that Theodore Baltazzi had in Constantinople, he was also a landowner in the Dardanelles, and Hungary. In Smyrna (Izmir), on the eastern Aegean coast, which was a significant town and had a historical link with the Baltazzi family, Theodore had a house on the waterfront on the edge of town. The view was described by Henrietta Iwan Muller who visited it in 1861. “There is a lovely view from her house. A viseo expanse of sea with high hills one each side: frigates steamers constantly coming in and going out.”

Eliza bore another nine children during her marriage to Theodore, although the youngest was born just after his death. In 1847, Helen was born, followed by Mary, known as Bibi, in 1848. In 1850, Alexander, their first son was born. The following year Hector, their second son was born. Aristides was born on the13th January 1853, and their fourth daughter, Eveline was born on 25th September 1854. Lolo, which was short for Charlotte, was born on the 11th November 1856, and the youngest son Harry was born on the 5th August, 1858, at Therapia.

In 1860 Theodore obtained Austrian nationality as opposed to just having a Austro-Hungarian passport and being a subject of the Empire. He was also appointed knight of the Franz Josef Order. He was in his early sixties.

But Theodore died in the same year, leaving Eliza, pregnant with their daughter Julia who was born on the 12th February 1861. Eliza was in her mid thirties and a very rich widow. Her husband had left each of his children six million gold francs, and Eliza was also left sufficient.

The eldest of Eliza’s children, Lizzie was nineteen, in 1862, when she married Albert Llewellyn Nugent, in the same Chapel, that Eliza had married Theodore and where Lizzie had been baptised. Eliza gave her consent to the marriage, which was required because Lizzie was not yet twenty-one, and therefore still a minor.

In 1857, Charles Alison, who had a varied career with the Embassy throughout the Ottoman Empire, appeared back in Constantinople. In February of that year he was Secretary at the Embassy, and then became the Chargé d’Affaires from December of that year through to July 1858. In October 1859 he moved to Syria, still part of the Ottoman Empire, and then in April 1860, he was appointed as the Envoy Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to Teheran.

Charles Alison had a reputation as a very flamboyant character from his early day as a Dragoman in the Embassy of Stratford Canning. He was not overawed by the Ambassador and there were numerous tails of his antic circulating in Constantinople from his time there. On one occasion having been sent for by Sir Stratford Canning, he entered the Ambassador’s study. However Sir Stratford Canning was busy, talking with one of his foreign colleagues, and Charles Alison was left standing. Where upon he jumped onto a side table and sat there swinging his legs, until the Ambassador hastily asked him to take a chair until he could attend to him.

Charles Alison had also kept a caique up at the Therapia Embassy, and the costume of a Turkish Caiquedji [boatman] in which he dressed up and then cruised the Upper Bosphorus offering his services to any particularly attractive ladies, and refusing any fare.

Charles Alison and Eliza obviously knew each other, and had probably known each other form when Charles Alison was first attached to the Embassy at Constantinople. But throughout most of this time Eliza had been married. However after the death of Theodore, Eliza was now free to marry again and Charles Alison was still single.

In Paris, at Her Majesty’s Embassy Chapel there, Charles Alison married Eliza Baltazzi on the 27th February 1863. But sadly, the marriage was not to be a long one.

Eliza was not well, as she travelled to Cairo with her daughter Helen, arriving there on 28th October. Henrietta Iwan Muller was living there at the time and renewed her acquaintance. She records in her journal “I have heard today that the Doctor considers her in extreme danger. What a kind friend she has been to me, what a kind generous friend she has been to … everyone! Oh I feel dreadfully out of spirits… fearing that I may soon hear some melancholy news then to dear Mrs Alison, oh what a loss it will be for many if anything happens to her.”

Henrietta kept in close contact with Eliza, who was living at the Hotel d’Orient in Cairo. Over the next few months, she visited her and wrote letters for her, and kept her daughter Helen, company as well. But despite a slight recovery, Eliza’s health was failing.

On the 10th December, Eliza’s mother, Euphrosyne Sarell arrived at her daughters bedside, with her brother Philip and youngest sister Helen. Nizza Crawford, another of her sisters arrived on the 13th.

Eliza was obviously concerned as to the future well being of her nine unmarried children, who were all still minors, and also very rich in their own rights. She asked Albin Vetsera the First Secretary of the Austrian Embassy to look after them as their guardian, and gave her consent also to his future marriage to Helen.

On Christmas Eve, Eliza signed her last will, witnessed by both the Austrian and British Consuls.

Henrietta Iwan Muller records the Christmas Day:

“The singing has gone off very well. I shall never forget this day. What solemn thing is a death bed scene. Dear Mrs Alison has received the sacrament and we have all partaken of it with her. I have played Pestal with her which she liked very much and asked me to play it again. We sung the Evening hymn Thy Will Be Done, which seemed to comfort her – I am thankful to have seen her once more, it may be the last time!”

Eliza died at 4 o’clock on Sunday 27th December 1863. The family stayed up with throughout the night.

Henrietta visited them on Monday 28th :