Self-introduction and the family members

I was born in Izmir, on August 28, 1924. My father Bernardo Triches was born on September 9, 1892, and passed away on August 13, 1968 in Izmir. My mother Lucia (née Tito) was born on April 14, 1898, and passed away on March 28, 1994 in Izmir.

My maternal grandmother Maria Concetta (née Di Paoli) had come all the way from Trani along with her brother who had been a shoemaker, to marry my grandfather Gennaro Tito here in Izmir but my grandfather never really liked his wife much. He was a shipmaster, and his ancestors were from Trani/Bari although he was born in Izmir. He and his wife had got eight children and my uncle Giovanni Tito was the only one among them who had studied out of Turkey (in Greece) to become a capitano di lungo corso (long distance ship captain). There was not a single school for higher education in Izmir then, and it was not that easy to study abroad either. Young men used to go straight into career after graduating usually from the French High School.

My father’s side had come from Venice. He used to work at Bill Giraud’s İzmir Pamuk Mensucat T.A.Ş (Izmir Cotton Mill Co., Inc.) as manager before the World War II began. With the sudden break out of the war, he had to quit the job, and later joined Şamli Şükrü (Şükrü of Damascus) in his textile enterprise. The Company was on the verge of bankruptcy at the time, and thanks to my father’s good organisational skills they survived it1. Following his retirement, he passed away. My father’s brother-in-law was also manager in another Giraud venture2; the wool factory (Yün Mensucat).

It was a big love, my mother and father had. I still save their love letters from the year 1914. They got married in 1919 and my elder brother Guglielmo was born in 1920. I was born in 1924 and my younger brother Benito was born in 1935. Our names were given after our grandparents. My name, for instance, was after Great Aunt Henrietta and my brother’s name Guglielmo was after Grandfather Guglielmo. My paternal grandmother’s name was Filomena actually but my mother was on the outs with her mother-in-law at the time, so she had given me the name of Filomena’s sister! She was a Carmelitan nun and her full name was Enrichetta Micaleff just like mine.

My elder brother Guglielmo had gone to school in Rhodes. Rhodes was an Italian colony, then. He had studied law in Rome, got married to an Italian and stayed there forever until he died. He did not fight during World War II, as Italy had not conscripted Italian subjects out of Italy into the army. He had four children who live in Italy. Benito, on the other hand, stayed in Izmir. He married Pierette (née Fantasia) who is a widow now. Their son lives in Istanbul and their daughter works in Singapore. Both are married to Turks.

There was a house behind the Italian School in Alsancak where Teresa Reggio used to live. There was a date palm tree standing next to it, hence the house was famously known as the ‘date palm house’. I was not born there, but that is the first house that I remember the best that we lived in when I was a child. Then we moved, in 1930, to Mesudiye Street3, No. 51. He had bought the house, but it was going to get demolished later. I grew up in that house. In my childhood days, Alsancak was a place full of foreigners (Levantines). The majority of the Levantines in Bornova and Buca was English, whereas in Alsancak, it was mostly the Italians and Maltese that you could see around – especially in the vicinity of the French School for Boys (St. Joseph). They had come from various spots in Italy like Trani, Bari, Brindisi or Naples; mostly as sailors on their boats they called trata. They liked it here, so they stayed, but held on to their Italian customs strictly. They ate pasta on Sundays. I remember people cooking homemade pasta on the streets around the Italian School when I was very young. They used to call the lunch meal stufado: meat cooked in boiling tomato sauce together with pasta cooked in the same sauce and dressed with grated cheese. Strascinati (orechiette), cappelletti, and spaghetti: everybody used to eat pasta on Sundays.

More food...

We used to eat lamb on Easter – the meat of lamb which we would raise in our backyard and we kids would feed with greens and sweets and play with for a week, thus were hardly able to say goodbye to this animal at around 10 in the morning of the Easter Saturday. The kids could not watch the scene as they would have got so used to the animals by the time of slaughter. All that is history now... We still eat lamb on Easter – the meat we buy at the butcher’s, though.

I have kept the tradition of cooking Easter cookies (tzurekia) until a few years ago, but I do not anymore. Ingrid4 cooks them and brings them to me. We used to take the dough –chicken as well- on baking trays to the baker’s shop, as we did not have an oven in our house then. There were two bakeries in our neighbourhood: one on Mesudiye St. called Paradiso, where now stands the tall language school building (Tömer) and the other one on the corner to St. Joseph School5. At the time we lived in Mustafabey, there was a third one, on which now is built the store Matraş on Gül St., where my husband’s sister Evelyne6 also lived – the ground floor of Christopher’s block, to be more specific. Christopher is my husband’s younger sister Rosalyne Dologh’s son. We would call for the boy at the market over to our apartment to have him take the tray to the bakery and bring it back. Then we purchased an oven. Everybody finally did. Those big, black baking trays are long gone.

On New Year’s Day we used to bake pita cookies (vassiliopites) for our guests as well as pita for the family to hide a coin into the latter so that it blesses the house. Whoever found the coin would be fortunate. Papa also used to give us kids a hundred pennies worth gold coin for luck on the same day. Now I do the same to my grandchildren. Pitas and Easter cookies are very similar except their form. Pitas are larger. We bake and eat pitas quite often during the year. Pita with milk, as my husband used to prefer. On Christmas we would give fancy forms to the sweet dough like that of a tree, bird, heart etc.

We ate no meat on Christmas Eve. Now that is over, we do eat meat. We used to eat fish instead on that day: fish with mayonnaise, salted roe – seafood, basically. Family members used to come together at Christmas dinner for celebration. They would go to church before the midnight for the service, and then return to their homes again to have hot chocolate and a special cake called Bûche de Noel together. We used to go to my sister-in-law’s house at such nights. Mr. Ferri who lived upstairs would come down to join us as well. He was a bank manager. There is another dessert that we often cook called finikia. It is quite like the Turkish kalburabasti – biscuits with cinnamon and chestnut in it, sweetened with boiling honey syrup. We still have it, but only at Christmas. However, we make pita all the time.

Formative years and marriage

The first school I went to was in Punta, and then I attended the Centrale. It was a strikingly beautiful school. In my day, the classes were very crowded, but at the time of the school’s demolition the class population had gone down to the average of 10-15 pupils. The majority of my classmates were Levantine. There were a few Turks and Jews, and the rest were Levantines of Italian descent. Leonardo Baba’s7 mother Maro Toctan was my desk-mate, for instance. She was born the same year as me; we have grown up together. I still see her at church. I was also schoolmates with Maria and Caterina Ventura. Not many of us are alive today.

I remember we read the poetry and the novels of Alessandro Manzoni at school: The Betrothed8, in particular. There was a time when the nuns and priests were not allowed to wear religious clothes and symbols anymore9. The nuns especially were looking for a way to obey the rule and be comfortable in their new outfit. So, they started to grow their hair a bit, put it up in a hairnet, and wear a long black/dark blue dress with a round white collar. That was their new uniform. It went on like this for some time, and I suppose more or less two decades ago the prohibition saw an amendment, this time allowing the nuns only to wear normal-looking, daily dresses with no religious significance whatsoever. Nowadays they prefer wearing colourful and stripy dresses but still with long sleeves.

At the end of my last grade in Centrale the war had broken out, and my mother, my brother and I had decided to go to Rome. We stayed there with my elder brother for six full years. My father had stayed in Izmir. Then we returned to Izmir because otherwise I had to serve my time in the Italian army even though I was a girl.

Well, my husband... When we were both young, he and his family used to live in Bornova. One day, while I was walking back home from Centrale, my friend and I went into a different street out of our usual route, and all of a sudden I saw my future husband there as a young man in his short pants for the first time in my life. He was standing next to his parents, who were there that day, I guess, to rent Mr. Sakaroff’s place. I was fourteen then, and had fallen in love with him at first sight. His name was Charles. Charles Micaleff. He was of Maltese origin. His ancestors had come from the then British Malta during the Crimean War, and were ship chandlers. I have not seen my future husband before that day, but then I started running into him on the Quay very often. In the meantime I had to go to Rome because of the war. I have never really talked to him before my departure for Rome. Anyway, years went by. I was young and beautiful and there were many young men around me who were willing to ask me out, but I was thinking of him and of going back to Izmir not only to find him there present, but also single. I was asking friends, relatives, whoever knew him if he got married, and they would answer: “No, he didn’t”. So, I felt a strong urge to return to Izmir. I remember I was thinking at the time if I was fooling myself with a vain hope, but I was also very determined to go to Izmir and see him after many years, and decide then whether to stay in Izmir or go back to Italy if things did not work the way I imagined in my head. So I went to Izmir and married him, and lived there forever. After a year of going out following my return, we got married in 1947.

My husband’s father was an export broker of olive oil and carpets. There used to be such stores in Darağaç, then. He had become partners with Antonio Ragusin10 and they had built a factory at the same location across the stadium. He opened another factory in Bornova later in 1938 and my husband was appointed to be in charge of the company they named Kristal. My husband’s younger brother Noel Micaleff is its CEO today. My husband also did some fishing too, with professional intentions, but it did not work.

At the time my husband and I became Turkish citizens, which was around 1987-88, I had to give up my Italian citizenship whereas my husband kept his English citizenship because he could and I was not able to. Then I took it back in the 1990s with the help of my elder brother in Italy.

From youth to adulthood: memorable people, places and facts from Izmir

There was a Turkish fishmonger in our neighbourhood called Şeref and a market keeper called Hacı – to whose shop the children used to go to buy marbles. There was a Jewish watchmaker called Sakaroff. Also the pharmacists: (Jean) Jullien and Costa. Costa’s store was very close to the Italian Cultural Centre on Kıbrıs Şehitleri St. He had two brothers. They used to make injections all the time. There was Schlosser the florist, dentist Vitel11 and (Felice) Capadona the constructor – his wife was a Micaleff. At fist Capadona used to own a small store, then he opened a larger one close to Costa’s store to sell dry goods (both his stores were on Mesudiye St.), and finally he became a renowned building contractor. He was a very hardworking and patient man. He used to sell glassware and stationary in that first tiny shop of his, and toward the 1960s became a great building contractor. He built many apartments in Alsancak and Karşıyaka12. In the same neighbourhood there were also the photographer Antonio Dragonetti’s shop who was very good at his job and took many photographs of our family over the years, and Chiarenza and Perini’s hardware store before coming to the Dominican Church.

Many of the Levantines left Izmir during World War II. The Maltese and Italians left for Rhodes and the Dodecanese13 which were occupied by Italy at the time. The English went mostly to India and Egypt. Some went to London, and a fewer of them went to Malta. Job restrictions of the 1930s14 and the Wealth Tax of 1940s made many of them to flee Izmir. A certain law had been passed that foresaw the prevention of alien craftsmen in Turkey from various fields of work15. I think that law was partly misunderstood and I also kind of feel that the context was left vague on purpose. By looking at the law closely, one could deduce that those who ran their own business were actually left out of its scope. Many people left nonetheless. My husband’s uncle, for instance, who was a hairdresser, had to leave for Algeria. On the other hand, there was a Giuseppe Dragonetti16, a lathe operator, he stayed. I wonder if each professional’s case was closely scrutinised and I wish that the law was implemented more subtly and carefully. Back then, there were many Levantines from French, Maltese and Italian origins living in Izmir. That was how we could fill up the classrooms, because we were many. Our parents were worn down by the Wealth Tax.

We used go to the pictures and plays when we were young. I remember my parents’ calling the old Izmir the ‘Petit Paris’. In their days before 1922, there were foreign theatrical troops visiting the city after their premiere in Paris. On Saturdays and Sundays we used to go to the cinema: either to Tayyare or Elhamra. You could see all the big foreign films of the time in those two cinema houses. There was another one in İkicesmelik as well, but we did not really prefer going there.

I used to play the piano when I was younger. Notable families used to have their children learn how to play an instrument then. No matter whether you liked it or not, you had to please your parents and learn how to do a petit montagnare. Television was not around yet, and radio was a rare thing to find in houses. However piano was common. Talented children would play the piano in the family gatherings. Teresa (Reggio) used to play the piano for us, and we would sing along. We also had a small band we called la cellulethat consisted of two members playing the guitar. I was not allowed to go out at nights freely even at the age of 22, so I would call my friends over to our place to entertain ourselves. It was not only for music; we would also play bingo and have chit-chat around a table until midnight. That was the entertainment for the youth in my social environment at the time. It would be Maro (Tito)17, Jinette (Ferri)18, Chiarenza, Harfuş (Bakioğlu)19, me and a few boys who made up of the crowd of those ‘parties’.

My parents used to go for night outs to Şehir Gazinosu (City Casino) which used to stand on the former place of the NATO headquarters in Alsancak, Göl Gazinosu (The Pond Casino) at the Izmir Fair area, and Küçük Kulüp (The Small Club) in Gümrük. The families used to go dining to Küçük Kulüp on Sundays, when I was little. The kids used to play around while families dined. I was friends with Jeanette since the age of 6, and we used to play together at such events. We are still good friends.

Families of a certain class used to have maids in their houses. The house workers like the chef or maid would be Greek villagers from Chios. They would visit their hometown once a year. There used to be some space beneath the ground level of the old houses and bedrooms in the upper floors for the use of the household workers. You would see many two-storey houses like that along the Quay, and the old Mesudiye, Aliotti and Bornova Streets of Alsancak. The majority of them are gone now. Everywhere is full of concrete walls; no breeze from the sea can reach inside. Those houses used to have a backyard where you would probably find a small pond, a doghouse, and the chickens strolling around etc. Nowadays new buildings are erected on the place of those properties. I cannot pinpoint its location, but our former house used to stand somewhere between Sevinç Pastanesi (Sevinç Patisserie) and Tömer. The Stano Family’s house used to stand across ours. Jeanette’s parents’ house was also near. There was a bakery called Paradiso20 and a patisserie called Consolo where you could buy delicious cakes in the exact vicinity. Paradiso was located on the intersection corner of Mesudiye St. and the narrow street on whose far end stands Salih İşgören School. The Chiarenza family used to live on that narrow street. And I remember the Giudici21, DiLernia, Paradiso and Fantasia families that lived on Gazi Kadınlar St. On the parallel street to the east, Muzaffer İzgu St. (former Petrokokino St.), there was hairdresser Wilma’s parlour and the Mirzan house across Peter Papi’s house where he still lives. Wilma had been the apprentice of my husband’s uncle who was a hairdresser and had to leave the country during the time the ‘small business owner law’ was put into force. Next to her used to live Georgette and Andre Mirzan – Jean Yves Özmirza’s parents. Very few of those families’ descendants reside in Izmir today. I suppose Mr. Mirzan used to work in one of the companies that belonged to the Girauds.

Over the years my husband and I had the chance to visit a number of places in Turkey like Antalya, Cappadocia and so on. We used to have many friends from Ayvalik. We bought a car in 1953 and took many trips across Turkey and abroad by car. We used to go to Rome, especially during the school summer holidays, to visit my elder brother who lived there. We had a German friend who used to work at the NATO headquarters in Izmir. We have met him in 1959. He and his family moved to Mainz in 1966 but somehow we always stayed in touch and continued visiting one another ever since they left. Their daughter who is 60 years old now is a friend of mine. She visits Turkey every year and stays with us for a couple of weeks. We travel to Pamukkale together. After my husband’s demise I went on about twelve or thirteen travels abroad with my good friend Katty Zakari22. We travelled to spots in the Far East like Vietnam. Portugal, Malta, Sicily, Italy, France, Germany, Poland in Europe. Katty organises great travel plans.

I am a housewife; I never worked out of home. However, I have always been very good at the housework. I used to prepare hundreds of kilos of tomato paste and fruit jam every year. My friends and I were old-fashioned housewives. I belong to a generation where the parents did not encourage their daughters to go to the university and have a career. I grew up with a strict moral discipline though, and raised my kids the same way. Maybe they did not enjoy it very much at the time, but I guess they are okay with it now. “You’ll be at home at 1! No buts allowed!” I would warn them.

Being a Levantine: whereabouts of an identity

I never encountered any sort of problem in regard to my being a Levantine – which stands for ‘foreigner’ for many. Quite the contrary, I always liked it here and we led a very comfortable life. Those who left had to leave for the reasons I mentioned. Especially between 1970 and 1980, many of them left, but I also know very well that they all regretted to have left this city. There are ones who have been living in Canada for the last two or three decades, I know they are still homesick. That is because, I think, wherever you go and whatever it takes, the real home is Izmir for someone who is from Izmir. My cousin in Argentina, for that matter, chose to return at quite an old age. Let me tell you a special memory of mine: My husband was a Rotarian. Once, we have been to one of those Rotarian meetings. At one stage a man came towards us speaking in Greek. Anyway, we replied in Greek. He looked a bit confused, so I said: “This is the Greek of Smyrniots23.” He said: “Yes, of course I know. I have been looking around for an old friend, Antonaki Micaleff. Do you know him by any chance?” I answered: “He is my father-in-law!” “Oh, really?” he said, “He used to be our neighbour in Bornova.” My husband’s father was very sick at the time, so, we did not tell the man about his state of health. The man was Greek. The Greeks who had to leave Turkey by any means tend to be very emotional people. Those who were from Izmir in that reunion often spoke in Turkish that day, and all seemed like they would cry at any moment but were also very happy, to be sitting together side by side. All expressed more or less the same feeling: “We are Greek and live in Greece but our homeland is here (i.e. Izmir, Minor Asia, Anatolia) and we have never forgotten, nor will ever forget that. That is why we are visiting here from time to time: to see the current state of our former houses.” His speech was so sentimental that it is pretty difficult for me now to put into words. Everybody was weeping quietly as he spoke. It looked to me like they had their conversations mostly in Turkish that day: The Greeks from Izmir and its periphery like Akhisar, Menemen etc. With the help of the Rotary Club, they have come to Izmir to see their hometown and possibly explore their ancestors’ houses. They said they lived in Greece happily but would never forget Anatolia. We were stunned and astonished by the passion they felt for their homeland. I have found that particularly familiar.

There are not many native Greeks in our family tree. There is only a Kakuli from Urla that I know who was married to my husband’s uncle. With the Greeks’ departure in the 1920s, the habit of the Levantines’ marrying the local Greeks almost came to a halt. Oh, and also Jeanette’s mother – she was Greek as well. One of my aunts had married a Turk and became Turk (Muslim) before the war. Her birth name was Anais, and then she became Nermin. That was a very unique case, her conversion. Otherwise such a marriage would not be possible at the time. Now there are many women in our community who marry Muslim men, but do not convert at all. What is more, same religion marriage is a rare thing to find.

Most of the Levantines could understand and speak Greek not only with their housemaids from Chios but also with one another. Italian Levantines used to speak Italian at home, but after all, the common language to communicate in the daily life, and the common ground for all those people from respective origins to meet was the French language. After WWII, English replaced French as the primal language of commerce and diplomacy. Levantine families used to send their children to the French School (St. Joseph), therefore the kids were growing up as eloquent French speakers. I used to speak with my siblings in Italian, however spoke in Italian and French to my children while raising them. My husband was a British subject but we did not really speak English as I could not speak the language. All of my kids went to the Italian School first, and then we sent my son Alex to my older brother in Rome and he studied chemical engineering there. After graduation, he returned to Izmir and started working at the company. My youngest daughter Ingrid went to the Turkish College and then studied chemical engineering like her brother did. My oldest daughter Marie-Therese got married after high school. Her husband Bruno is Italian. The two lived in Izmir for around forty years, but after they retired they moved to Italy. One of their kids lives in Genoa, and the other one lives in the USA. Alex, Ingrid and both of their families live in Izmir. My daughters’ families and I used to live in the same building until Marie-Therese and Bruno’s departure to Italy.

We can speak Greek but cannot really read it. Once I was in Greece and have heard something interesting on TV. I asked what it was about to a person sitting next to me. She replied: “Are you kidding me? How come you cannot understand what is being said while you can speak Greek well?” However, that was the case24. As you see, we can start a conversation in French, then switch to Italian and continue in Greek whenever we feel like it, because I know that you, as a Levantine, are quite like me, therefore can understand what I am saying. Once I have met a French person in Izmir, and she was quite surprised with the way we communicated with one another. She has asked me what kind of a language we have been speaking. The truth is, we mix the languages. Perhaps we cannot speak all those languages we speak perfectly, but we can still speak them. I feel very comfortable while speaking French, Italian, Greek and Turkish. So do my children. All those languages are mother tongues to us. I guess that makes us polyglots, doesn’t it?

We are proud of being Levantines. The Europeans use the word ‘Levantine’ in a pejorative manner, as if the Levantines are tricky people or something. Once I have said to my granddaughter Barbara’s (Bonatti) mother-in-law in Genoa that we were Levantines, and she reacted: “What!?” “No, no,” I have tried to explain, “it is not the way you think”. We call ourselves Levantines and we have no problem with that, but we know that the word has a negative connotation in the European public sphere. I think they understand ‘opportunism’ from that word. There might have been opportunists, adventurers among the first Levantines that reached Turkey, but not all of them could have shared the same intentions. After all, we are neither Italian nor English. I may have the passports of both nations but I am from neither of them really. The English Levantines in Bornova might have had different customs, but Italian Levantines like us differ from them in that respect. I remember the Matteis family from Bornova. Its descendants must still be living there, as well as those of D’Andrias and La Fontaines. The Whitalls largely fled. One of the last remainders, June, migrated to Australia. Being a Levantine is perhaps like an upper identity that covers those various sub-identities. I do not know... What I do know is that when I go to Italy, I do not feel myself Italian there. After all, Italians call me ‘Signora Turco’... My children do not find their true selves in Malta, just because they are Maltese Levantines. This is like being neither fish nor flesh. We are not Turkish either. Our homeland is Turkey but hey, we are not ethnically Turkish, so I feel myself at ease only in the category of ‘Levantine’. And I believe that the Levantine culture contributed a lot to the urban traditions rooted in Izmir. Therefore we have many things in common with the old Muslim families of this city.

Remembering Smyrna 1922

Many Levantines from Italian, Maltese, and French etc. descents have inhabited several districts of Izmir at the time of 1922 Fire. War ships of every nation could be seen on the bay to collect their citizens and take them away. Before the fire broke out, all the Italians of Smyrna had gathered in the Italian School, and an armed mariner with bayonet was protecting them. My father went to Gündoğdu Square to see if the ships arrived or not. The Italians stepped out of the school and began to walk toward the Quay. Their walk lasted three long hours. The streets were so crowded that the Quay was bursting at the seams. There was a flow of people drifting toward the quayside and carrying their valuable stuff – the only stuff that they could think of taking with them before leaving their houses in panic. Some of them lost their stuff or had to leave it at one point during that exhausting walk. I remember my mother having said once that one could make a fortune on that day picking up the silverware he’d find on his way, provided that he did not care for his own life. Masses congregated on the Quay. My parents and my older brother who was two years old at the time were among them. My grandfather saw one of his friends departing on a small boat, and called out to him: “Hey Antoine! Take my kid!” He replied: “I can’t. I have my own family to take care of.” Father threw his son away to a mariner, though. The mariner grabbed my baby brother. My parents fell into the water in that turmoil while boarding on the boat. Mother had to travel all the way to Italy with her wet clothes on. Since then she suffered constantly from the rheumatism. They stayed in the refugee camps in Italy for six or seven months and then returned to Izmir. My husband’s parents had sailed to Malta on British boats. Those days are history now. Whenever a war broke out, all nations would send out their war ships to save their citizens. Many of those who left Izmir in 1922 returned after a while of staying abroad. They could stay wherever they had fled to, but many of them preferred returning. One of the main reasons for that was the fact that the part of Izmir known as Alsancak today had been occupied largely by the Levantines, and had not really been destroyed by the fire. The fire had stopped at the border of Sair Esref Boulevard. This reminds me of another memory of mine: By the time we lived in Mustafabey neighbourhood, I was interested in renting another house on Talatpaşa Boulevard. By chance we moved into there – yet another apartment with the address number 51. Anyway, there were some vacant lots around the house which used to be crop lands before then. During the construction process of a particular building in the area, I remember my husband and I have witnessed the workers’ finding pieces of human bones while digging the soil. As we came to understand that the site was supposed to be the former place of a Greek Church St. John and that the bones probably belonged to its graveyard, I have started seeing nightmares and wanted to initiate a memorial service for the souls of the dead.

Back to today...

Since my husband passed away eleven years ago, I have been living in this apartment, in the same building with my daughter Ingrid and her family. My children always had their own homes that they lived in with their families. I had my own home, too. However, after a certain age, some people begin to feel the necessity to live closer to their beloved ones. So, I moved here and I am very happy to be living two floors below my daughter’s apartment, but still on my own.

I was born in Izmir, on August 28, 1924. My father Bernardo Triches was born on September 9, 1892, and passed away on August 13, 1968 in Izmir. My mother Lucia (née Tito) was born on April 14, 1898, and passed away on March 28, 1994 in Izmir.

My maternal grandmother Maria Concetta (née Di Paoli) had come all the way from Trani along with her brother who had been a shoemaker, to marry my grandfather Gennaro Tito here in Izmir but my grandfather never really liked his wife much. He was a shipmaster, and his ancestors were from Trani/Bari although he was born in Izmir. He and his wife had got eight children and my uncle Giovanni Tito was the only one among them who had studied out of Turkey (in Greece) to become a capitano di lungo corso (long distance ship captain). There was not a single school for higher education in Izmir then, and it was not that easy to study abroad either. Young men used to go straight into career after graduating usually from the French High School.

Left to right: Antonio Triches (standing), Silvio Valente (sitting), Enrichetta ‘Etta’ Triches, Bernardo Triches, Lucia (née Tito) Triches, Filomena Triches, Anais (née Triches) Valente (later Nermin), Guglielmo ‘Memo’ Triches. (Early 1930s, Buca) |

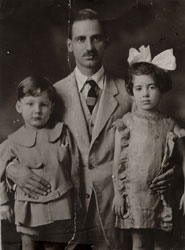

Anthony Micaleff with his children Antoine and Evelyne Micaleff (around 1921-2) |

Left to right: Lucia, Enrichetta, Bernardo and Guglielmo Triches (1924) |

My father’s side had come from Venice. He used to work at Bill Giraud’s İzmir Pamuk Mensucat T.A.Ş (Izmir Cotton Mill Co., Inc.) as manager before the World War II began. With the sudden break out of the war, he had to quit the job, and later joined Şamli Şükrü (Şükrü of Damascus) in his textile enterprise. The Company was on the verge of bankruptcy at the time, and thanks to my father’s good organisational skills they survived it1. Following his retirement, he passed away. My father’s brother-in-law was also manager in another Giraud venture2; the wool factory (Yün Mensucat).

It was a big love, my mother and father had. I still save their love letters from the year 1914. They got married in 1919 and my elder brother Guglielmo was born in 1920. I was born in 1924 and my younger brother Benito was born in 1935. Our names were given after our grandparents. My name, for instance, was after Great Aunt Henrietta and my brother’s name Guglielmo was after Grandfather Guglielmo. My paternal grandmother’s name was Filomena actually but my mother was on the outs with her mother-in-law at the time, so she had given me the name of Filomena’s sister! She was a Carmelitan nun and her full name was Enrichetta Micaleff just like mine.

My elder brother Guglielmo had gone to school in Rhodes. Rhodes was an Italian colony, then. He had studied law in Rome, got married to an Italian and stayed there forever until he died. He did not fight during World War II, as Italy had not conscripted Italian subjects out of Italy into the army. He had four children who live in Italy. Benito, on the other hand, stayed in Izmir. He married Pierette (née Fantasia) who is a widow now. Their son lives in Istanbul and their daughter works in Singapore. Both are married to Turks.

There was a house behind the Italian School in Alsancak where Teresa Reggio used to live. There was a date palm tree standing next to it, hence the house was famously known as the ‘date palm house’. I was not born there, but that is the first house that I remember the best that we lived in when I was a child. Then we moved, in 1930, to Mesudiye Street3, No. 51. He had bought the house, but it was going to get demolished later. I grew up in that house. In my childhood days, Alsancak was a place full of foreigners (Levantines). The majority of the Levantines in Bornova and Buca was English, whereas in Alsancak, it was mostly the Italians and Maltese that you could see around – especially in the vicinity of the French School for Boys (St. Joseph). They had come from various spots in Italy like Trani, Bari, Brindisi or Naples; mostly as sailors on their boats they called trata. They liked it here, so they stayed, but held on to their Italian customs strictly. They ate pasta on Sundays. I remember people cooking homemade pasta on the streets around the Italian School when I was very young. They used to call the lunch meal stufado: meat cooked in boiling tomato sauce together with pasta cooked in the same sauce and dressed with grated cheese. Strascinati (orechiette), cappelletti, and spaghetti: everybody used to eat pasta on Sundays.

More food...

We used to eat lamb on Easter – the meat of lamb which we would raise in our backyard and we kids would feed with greens and sweets and play with for a week, thus were hardly able to say goodbye to this animal at around 10 in the morning of the Easter Saturday. The kids could not watch the scene as they would have got so used to the animals by the time of slaughter. All that is history now... We still eat lamb on Easter – the meat we buy at the butcher’s, though.

I have kept the tradition of cooking Easter cookies (tzurekia) until a few years ago, but I do not anymore. Ingrid4 cooks them and brings them to me. We used to take the dough –chicken as well- on baking trays to the baker’s shop, as we did not have an oven in our house then. There were two bakeries in our neighbourhood: one on Mesudiye St. called Paradiso, where now stands the tall language school building (Tömer) and the other one on the corner to St. Joseph School5. At the time we lived in Mustafabey, there was a third one, on which now is built the store Matraş on Gül St., where my husband’s sister Evelyne6 also lived – the ground floor of Christopher’s block, to be more specific. Christopher is my husband’s younger sister Rosalyne Dologh’s son. We would call for the boy at the market over to our apartment to have him take the tray to the bakery and bring it back. Then we purchased an oven. Everybody finally did. Those big, black baking trays are long gone.

On New Year’s Day we used to bake pita cookies (vassiliopites) for our guests as well as pita for the family to hide a coin into the latter so that it blesses the house. Whoever found the coin would be fortunate. Papa also used to give us kids a hundred pennies worth gold coin for luck on the same day. Now I do the same to my grandchildren. Pitas and Easter cookies are very similar except their form. Pitas are larger. We bake and eat pitas quite often during the year. Pita with milk, as my husband used to prefer. On Christmas we would give fancy forms to the sweet dough like that of a tree, bird, heart etc.

We ate no meat on Christmas Eve. Now that is over, we do eat meat. We used to eat fish instead on that day: fish with mayonnaise, salted roe – seafood, basically. Family members used to come together at Christmas dinner for celebration. They would go to church before the midnight for the service, and then return to their homes again to have hot chocolate and a special cake called Bûche de Noel together. We used to go to my sister-in-law’s house at such nights. Mr. Ferri who lived upstairs would come down to join us as well. He was a bank manager. There is another dessert that we often cook called finikia. It is quite like the Turkish kalburabasti – biscuits with cinnamon and chestnut in it, sweetened with boiling honey syrup. We still have it, but only at Christmas. However, we make pita all the time.

Formative years and marriage

The first school I went to was in Punta, and then I attended the Centrale. It was a strikingly beautiful school. In my day, the classes were very crowded, but at the time of the school’s demolition the class population had gone down to the average of 10-15 pupils. The majority of my classmates were Levantine. There were a few Turks and Jews, and the rest were Levantines of Italian descent. Leonardo Baba’s7 mother Maro Toctan was my desk-mate, for instance. She was born the same year as me; we have grown up together. I still see her at church. I was also schoolmates with Maria and Caterina Ventura. Not many of us are alive today.

I remember we read the poetry and the novels of Alessandro Manzoni at school: The Betrothed8, in particular. There was a time when the nuns and priests were not allowed to wear religious clothes and symbols anymore9. The nuns especially were looking for a way to obey the rule and be comfortable in their new outfit. So, they started to grow their hair a bit, put it up in a hairnet, and wear a long black/dark blue dress with a round white collar. That was their new uniform. It went on like this for some time, and I suppose more or less two decades ago the prohibition saw an amendment, this time allowing the nuns only to wear normal-looking, daily dresses with no religious significance whatsoever. Nowadays they prefer wearing colourful and stripy dresses but still with long sleeves.

At the end of my last grade in Centrale the war had broken out, and my mother, my brother and I had decided to go to Rome. We stayed there with my elder brother for six full years. My father had stayed in Izmir. Then we returned to Izmir because otherwise I had to serve my time in the Italian army even though I was a girl.

Well, my husband... When we were both young, he and his family used to live in Bornova. One day, while I was walking back home from Centrale, my friend and I went into a different street out of our usual route, and all of a sudden I saw my future husband there as a young man in his short pants for the first time in my life. He was standing next to his parents, who were there that day, I guess, to rent Mr. Sakaroff’s place. I was fourteen then, and had fallen in love with him at first sight. His name was Charles. Charles Micaleff. He was of Maltese origin. His ancestors had come from the then British Malta during the Crimean War, and were ship chandlers. I have not seen my future husband before that day, but then I started running into him on the Quay very often. In the meantime I had to go to Rome because of the war. I have never really talked to him before my departure for Rome. Anyway, years went by. I was young and beautiful and there were many young men around me who were willing to ask me out, but I was thinking of him and of going back to Izmir not only to find him there present, but also single. I was asking friends, relatives, whoever knew him if he got married, and they would answer: “No, he didn’t”. So, I felt a strong urge to return to Izmir. I remember I was thinking at the time if I was fooling myself with a vain hope, but I was also very determined to go to Izmir and see him after many years, and decide then whether to stay in Izmir or go back to Italy if things did not work the way I imagined in my head. So I went to Izmir and married him, and lived there forever. After a year of going out following my return, we got married in 1947.

Centrale School performance souvenir photo of “Zurica”, early 1940s. |

Enrichetta in front of the Micaleff House on Mesudiye St. (Now Kıbrıs Şehitleri St.), late 30s-early 40s |

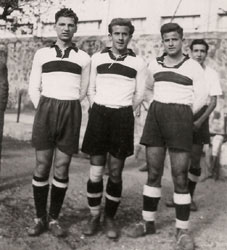

(left to right) Charles Micaleff, Edwin Clarke, Joe Clarke, mid 1940s. |

My husband’s father was an export broker of olive oil and carpets. There used to be such stores in Darağaç, then. He had become partners with Antonio Ragusin10 and they had built a factory at the same location across the stadium. He opened another factory in Bornova later in 1938 and my husband was appointed to be in charge of the company they named Kristal. My husband’s younger brother Noel Micaleff is its CEO today. My husband also did some fishing too, with professional intentions, but it did not work.

At the time my husband and I became Turkish citizens, which was around 1987-88, I had to give up my Italian citizenship whereas my husband kept his English citizenship because he could and I was not able to. Then I took it back in the 1990s with the help of my elder brother in Italy.

From youth to adulthood: memorable people, places and facts from Izmir

There was a Turkish fishmonger in our neighbourhood called Şeref and a market keeper called Hacı – to whose shop the children used to go to buy marbles. There was a Jewish watchmaker called Sakaroff. Also the pharmacists: (Jean) Jullien and Costa. Costa’s store was very close to the Italian Cultural Centre on Kıbrıs Şehitleri St. He had two brothers. They used to make injections all the time. There was Schlosser the florist, dentist Vitel11 and (Felice) Capadona the constructor – his wife was a Micaleff. At fist Capadona used to own a small store, then he opened a larger one close to Costa’s store to sell dry goods (both his stores were on Mesudiye St.), and finally he became a renowned building contractor. He was a very hardworking and patient man. He used to sell glassware and stationary in that first tiny shop of his, and toward the 1960s became a great building contractor. He built many apartments in Alsancak and Karşıyaka12. In the same neighbourhood there were also the photographer Antonio Dragonetti’s shop who was very good at his job and took many photographs of our family over the years, and Chiarenza and Perini’s hardware store before coming to the Dominican Church.

Many of the Levantines left Izmir during World War II. The Maltese and Italians left for Rhodes and the Dodecanese13 which were occupied by Italy at the time. The English went mostly to India and Egypt. Some went to London, and a fewer of them went to Malta. Job restrictions of the 1930s14 and the Wealth Tax of 1940s made many of them to flee Izmir. A certain law had been passed that foresaw the prevention of alien craftsmen in Turkey from various fields of work15. I think that law was partly misunderstood and I also kind of feel that the context was left vague on purpose. By looking at the law closely, one could deduce that those who ran their own business were actually left out of its scope. Many people left nonetheless. My husband’s uncle, for instance, who was a hairdresser, had to leave for Algeria. On the other hand, there was a Giuseppe Dragonetti16, a lathe operator, he stayed. I wonder if each professional’s case was closely scrutinised and I wish that the law was implemented more subtly and carefully. Back then, there were many Levantines from French, Maltese and Italian origins living in Izmir. That was how we could fill up the classrooms, because we were many. Our parents were worn down by the Wealth Tax.

We used go to the pictures and plays when we were young. I remember my parents’ calling the old Izmir the ‘Petit Paris’. In their days before 1922, there were foreign theatrical troops visiting the city after their premiere in Paris. On Saturdays and Sundays we used to go to the cinema: either to Tayyare or Elhamra. You could see all the big foreign films of the time in those two cinema houses. There was another one in İkicesmelik as well, but we did not really prefer going there.

I used to play the piano when I was younger. Notable families used to have their children learn how to play an instrument then. No matter whether you liked it or not, you had to please your parents and learn how to do a petit montagnare. Television was not around yet, and radio was a rare thing to find in houses. However piano was common. Talented children would play the piano in the family gatherings. Teresa (Reggio) used to play the piano for us, and we would sing along. We also had a small band we called la cellulethat consisted of two members playing the guitar. I was not allowed to go out at nights freely even at the age of 22, so I would call my friends over to our place to entertain ourselves. It was not only for music; we would also play bingo and have chit-chat around a table until midnight. That was the entertainment for the youth in my social environment at the time. It would be Maro (Tito)17, Jinette (Ferri)18, Chiarenza, Harfuş (Bakioğlu)19, me and a few boys who made up of the crowd of those ‘parties’.

My parents used to go for night outs to Şehir Gazinosu (City Casino) which used to stand on the former place of the NATO headquarters in Alsancak, Göl Gazinosu (The Pond Casino) at the Izmir Fair area, and Küçük Kulüp (The Small Club) in Gümrük. The families used to go dining to Küçük Kulüp on Sundays, when I was little. The kids used to play around while families dined. I was friends with Jeanette since the age of 6, and we used to play together at such events. We are still good friends.

Families of a certain class used to have maids in their houses. The house workers like the chef or maid would be Greek villagers from Chios. They would visit their hometown once a year. There used to be some space beneath the ground level of the old houses and bedrooms in the upper floors for the use of the household workers. You would see many two-storey houses like that along the Quay, and the old Mesudiye, Aliotti and Bornova Streets of Alsancak. The majority of them are gone now. Everywhere is full of concrete walls; no breeze from the sea can reach inside. Those houses used to have a backyard where you would probably find a small pond, a doghouse, and the chickens strolling around etc. Nowadays new buildings are erected on the place of those properties. I cannot pinpoint its location, but our former house used to stand somewhere between Sevinç Pastanesi (Sevinç Patisserie) and Tömer. The Stano Family’s house used to stand across ours. Jeanette’s parents’ house was also near. There was a bakery called Paradiso20 and a patisserie called Consolo where you could buy delicious cakes in the exact vicinity. Paradiso was located on the intersection corner of Mesudiye St. and the narrow street on whose far end stands Salih İşgören School. The Chiarenza family used to live on that narrow street. And I remember the Giudici21, DiLernia, Paradiso and Fantasia families that lived on Gazi Kadınlar St. On the parallel street to the east, Muzaffer İzgu St. (former Petrokokino St.), there was hairdresser Wilma’s parlour and the Mirzan house across Peter Papi’s house where he still lives. Wilma had been the apprentice of my husband’s uncle who was a hairdresser and had to leave the country during the time the ‘small business owner law’ was put into force. Next to her used to live Georgette and Andre Mirzan – Jean Yves Özmirza’s parents. Very few of those families’ descendants reside in Izmir today. I suppose Mr. Mirzan used to work in one of the companies that belonged to the Girauds.

Over the years my husband and I had the chance to visit a number of places in Turkey like Antalya, Cappadocia and so on. We used to have many friends from Ayvalik. We bought a car in 1953 and took many trips across Turkey and abroad by car. We used to go to Rome, especially during the school summer holidays, to visit my elder brother who lived there. We had a German friend who used to work at the NATO headquarters in Izmir. We have met him in 1959. He and his family moved to Mainz in 1966 but somehow we always stayed in touch and continued visiting one another ever since they left. Their daughter who is 60 years old now is a friend of mine. She visits Turkey every year and stays with us for a couple of weeks. We travel to Pamukkale together. After my husband’s demise I went on about twelve or thirteen travels abroad with my good friend Katty Zakari22. We travelled to spots in the Far East like Vietnam. Portugal, Malta, Sicily, Italy, France, Germany, Poland in Europe. Katty organises great travel plans.

I am a housewife; I never worked out of home. However, I have always been very good at the housework. I used to prepare hundreds of kilos of tomato paste and fruit jam every year. My friends and I were old-fashioned housewives. I belong to a generation where the parents did not encourage their daughters to go to the university and have a career. I grew up with a strict moral discipline though, and raised my kids the same way. Maybe they did not enjoy it very much at the time, but I guess they are okay with it now. “You’ll be at home at 1! No buts allowed!” I would warn them.

Being a Levantine: whereabouts of an identity

I never encountered any sort of problem in regard to my being a Levantine – which stands for ‘foreigner’ for many. Quite the contrary, I always liked it here and we led a very comfortable life. Those who left had to leave for the reasons I mentioned. Especially between 1970 and 1980, many of them left, but I also know very well that they all regretted to have left this city. There are ones who have been living in Canada for the last two or three decades, I know they are still homesick. That is because, I think, wherever you go and whatever it takes, the real home is Izmir for someone who is from Izmir. My cousin in Argentina, for that matter, chose to return at quite an old age. Let me tell you a special memory of mine: My husband was a Rotarian. Once, we have been to one of those Rotarian meetings. At one stage a man came towards us speaking in Greek. Anyway, we replied in Greek. He looked a bit confused, so I said: “This is the Greek of Smyrniots23.” He said: “Yes, of course I know. I have been looking around for an old friend, Antonaki Micaleff. Do you know him by any chance?” I answered: “He is my father-in-law!” “Oh, really?” he said, “He used to be our neighbour in Bornova.” My husband’s father was very sick at the time, so, we did not tell the man about his state of health. The man was Greek. The Greeks who had to leave Turkey by any means tend to be very emotional people. Those who were from Izmir in that reunion often spoke in Turkish that day, and all seemed like they would cry at any moment but were also very happy, to be sitting together side by side. All expressed more or less the same feeling: “We are Greek and live in Greece but our homeland is here (i.e. Izmir, Minor Asia, Anatolia) and we have never forgotten, nor will ever forget that. That is why we are visiting here from time to time: to see the current state of our former houses.” His speech was so sentimental that it is pretty difficult for me now to put into words. Everybody was weeping quietly as he spoke. It looked to me like they had their conversations mostly in Turkish that day: The Greeks from Izmir and its periphery like Akhisar, Menemen etc. With the help of the Rotary Club, they have come to Izmir to see their hometown and possibly explore their ancestors’ houses. They said they lived in Greece happily but would never forget Anatolia. We were stunned and astonished by the passion they felt for their homeland. I have found that particularly familiar.

There are not many native Greeks in our family tree. There is only a Kakuli from Urla that I know who was married to my husband’s uncle. With the Greeks’ departure in the 1920s, the habit of the Levantines’ marrying the local Greeks almost came to a halt. Oh, and also Jeanette’s mother – she was Greek as well. One of my aunts had married a Turk and became Turk (Muslim) before the war. Her birth name was Anais, and then she became Nermin. That was a very unique case, her conversion. Otherwise such a marriage would not be possible at the time. Now there are many women in our community who marry Muslim men, but do not convert at all. What is more, same religion marriage is a rare thing to find.

Most of the Levantines could understand and speak Greek not only with their housemaids from Chios but also with one another. Italian Levantines used to speak Italian at home, but after all, the common language to communicate in the daily life, and the common ground for all those people from respective origins to meet was the French language. After WWII, English replaced French as the primal language of commerce and diplomacy. Levantine families used to send their children to the French School (St. Joseph), therefore the kids were growing up as eloquent French speakers. I used to speak with my siblings in Italian, however spoke in Italian and French to my children while raising them. My husband was a British subject but we did not really speak English as I could not speak the language. All of my kids went to the Italian School first, and then we sent my son Alex to my older brother in Rome and he studied chemical engineering there. After graduation, he returned to Izmir and started working at the company. My youngest daughter Ingrid went to the Turkish College and then studied chemical engineering like her brother did. My oldest daughter Marie-Therese got married after high school. Her husband Bruno is Italian. The two lived in Izmir for around forty years, but after they retired they moved to Italy. One of their kids lives in Genoa, and the other one lives in the USA. Alex, Ingrid and both of their families live in Izmir. My daughters’ families and I used to live in the same building until Marie-Therese and Bruno’s departure to Italy.

We can speak Greek but cannot really read it. Once I was in Greece and have heard something interesting on TV. I asked what it was about to a person sitting next to me. She replied: “Are you kidding me? How come you cannot understand what is being said while you can speak Greek well?” However, that was the case24. As you see, we can start a conversation in French, then switch to Italian and continue in Greek whenever we feel like it, because I know that you, as a Levantine, are quite like me, therefore can understand what I am saying. Once I have met a French person in Izmir, and she was quite surprised with the way we communicated with one another. She has asked me what kind of a language we have been speaking. The truth is, we mix the languages. Perhaps we cannot speak all those languages we speak perfectly, but we can still speak them. I feel very comfortable while speaking French, Italian, Greek and Turkish. So do my children. All those languages are mother tongues to us. I guess that makes us polyglots, doesn’t it?

Members of the Micaleff and Triches families together at the entrance to St. John’s Cathedral on Sehit Nevres Blvd. |

Pupils of the Italian School in Bayraklı |

My father, Bernardo Triches in a horse farm in Mersinli |

We are proud of being Levantines. The Europeans use the word ‘Levantine’ in a pejorative manner, as if the Levantines are tricky people or something. Once I have said to my granddaughter Barbara’s (Bonatti) mother-in-law in Genoa that we were Levantines, and she reacted: “What!?” “No, no,” I have tried to explain, “it is not the way you think”. We call ourselves Levantines and we have no problem with that, but we know that the word has a negative connotation in the European public sphere. I think they understand ‘opportunism’ from that word. There might have been opportunists, adventurers among the first Levantines that reached Turkey, but not all of them could have shared the same intentions. After all, we are neither Italian nor English. I may have the passports of both nations but I am from neither of them really. The English Levantines in Bornova might have had different customs, but Italian Levantines like us differ from them in that respect. I remember the Matteis family from Bornova. Its descendants must still be living there, as well as those of D’Andrias and La Fontaines. The Whitalls largely fled. One of the last remainders, June, migrated to Australia. Being a Levantine is perhaps like an upper identity that covers those various sub-identities. I do not know... What I do know is that when I go to Italy, I do not feel myself Italian there. After all, Italians call me ‘Signora Turco’... My children do not find their true selves in Malta, just because they are Maltese Levantines. This is like being neither fish nor flesh. We are not Turkish either. Our homeland is Turkey but hey, we are not ethnically Turkish, so I feel myself at ease only in the category of ‘Levantine’. And I believe that the Levantine culture contributed a lot to the urban traditions rooted in Izmir. Therefore we have many things in common with the old Muslim families of this city.

Remembering Smyrna 1922

Many Levantines from Italian, Maltese, and French etc. descents have inhabited several districts of Izmir at the time of 1922 Fire. War ships of every nation could be seen on the bay to collect their citizens and take them away. Before the fire broke out, all the Italians of Smyrna had gathered in the Italian School, and an armed mariner with bayonet was protecting them. My father went to Gündoğdu Square to see if the ships arrived or not. The Italians stepped out of the school and began to walk toward the Quay. Their walk lasted three long hours. The streets were so crowded that the Quay was bursting at the seams. There was a flow of people drifting toward the quayside and carrying their valuable stuff – the only stuff that they could think of taking with them before leaving their houses in panic. Some of them lost their stuff or had to leave it at one point during that exhausting walk. I remember my mother having said once that one could make a fortune on that day picking up the silverware he’d find on his way, provided that he did not care for his own life. Masses congregated on the Quay. My parents and my older brother who was two years old at the time were among them. My grandfather saw one of his friends departing on a small boat, and called out to him: “Hey Antoine! Take my kid!” He replied: “I can’t. I have my own family to take care of.” Father threw his son away to a mariner, though. The mariner grabbed my baby brother. My parents fell into the water in that turmoil while boarding on the boat. Mother had to travel all the way to Italy with her wet clothes on. Since then she suffered constantly from the rheumatism. They stayed in the refugee camps in Italy for six or seven months and then returned to Izmir. My husband’s parents had sailed to Malta on British boats. Those days are history now. Whenever a war broke out, all nations would send out their war ships to save their citizens. Many of those who left Izmir in 1922 returned after a while of staying abroad. They could stay wherever they had fled to, but many of them preferred returning. One of the main reasons for that was the fact that the part of Izmir known as Alsancak today had been occupied largely by the Levantines, and had not really been destroyed by the fire. The fire had stopped at the border of Sair Esref Boulevard. This reminds me of another memory of mine: By the time we lived in Mustafabey neighbourhood, I was interested in renting another house on Talatpaşa Boulevard. By chance we moved into there – yet another apartment with the address number 51. Anyway, there were some vacant lots around the house which used to be crop lands before then. During the construction process of a particular building in the area, I remember my husband and I have witnessed the workers’ finding pieces of human bones while digging the soil. As we came to understand that the site was supposed to be the former place of a Greek Church St. John and that the bones probably belonged to its graveyard, I have started seeing nightmares and wanted to initiate a memorial service for the souls of the dead.

Back to today...

Since my husband passed away eleven years ago, I have been living in this apartment, in the same building with my daughter Ingrid and her family. My children always had their own homes that they lived in with their families. I had my own home, too. However, after a certain age, some people begin to feel the necessity to live closer to their beloved ones. So, I moved here and I am very happy to be living two floors below my daughter’s apartment, but still on my own.

1 According to the author Melih Gürsoy (in Bizim İzmirimiz, 1993: 239-41; 267), Brothers Şükrü, Nafiz and Mehmet Şamlı (later Şanlı) were partners with the Girauds in their Izmir Pamuk Mensucat, founded in 1910. Other notable partners included (an unknown) Braggiotti, Alber Aliotti, Henry Singler and the former governor of Izmir, Rahmi Bey. The company was one of the biggest of the Aegean and Turkey in the manufacturing and exporting of a range of textile products including canvas, English sewing thread etc., before the Wealth Tax act of 1942 (Varlık Vergisi) charged the company a great deal of tax, and damaged its assets on an immense level. The Şanlı family continued to venture in the textile and pharmaceutical industries in the years to come.

2 Oriental Carpet, İzmir Pamuk Mensucat, İzmir Basma and İzmir Yün Mensucat factories/companies can be listed among the enterprises led by the Girauds.

3 Today Kıbrıs Şehitleri St.

4 Enrichetta Micaleff’s daughter Ingrid Braggiotti who was also present at the interview.

5 I.B. states that Paradiso had been active until the mid 1970s. The baker’s shop that faces the school building still stands in the same location.

6 She was married Joe Clarke, E.M. states.

7 He currently works at Izmir St. Joseph College.

8 I Promessi Sposi (1827) in Italian: one of the leading novels of the Italian literature.

9 There have been enactments in 1924 and 1935 in Turkey, concerning the compulsory dress codes in public and private education institutions, which were in line with the secularisation movement, and the ban on the wearing of religious symbols at school was related to that.

10 According to Ingrid Braggiotti, he passed away in 1960, and his wife and kids withdrew from the partnership. Mr. And Mrs. Ragusin’s daughter Odetta is married to Maurizio Braggiotti and lives in Izmir. Their sons Gianni and Mariano (Rino) live in Izmir and are in the rubber business. Their youngest daughter Alba is married to Erdel Vidori and lives in the USA today.

11 I.B. states that he was related to the Whitall family. During an occupational accident, he got injured on his eye and had to change job, so he opened up a flower shop on Mesudiye/Kıbrıs Şehitleri St. and was also an occasional funeral undertaker.

12 Gürsoy (1993:257) states that Capadona had been very active mainly in the period between 1958 and 1963.

13 The Twelve Islands.

14 According to law no. 2007 enacted on June 1, 1932, those who lived in Turkey and were not Turkish citizens were not allowed to do the following professions: shoemaker, musician, photographer; barber, typesetter, broker, midwife; suit/dress, cap and shoe manufacturer; stock market purchaser, seller of monopoly products (i.e. tobacco and alcohol), interpreter and tourist guide; worker in construction, steel and wood industries; worker in water, lightning, heating, and communication works; driver and assistant driver, shipment worker, all kinds of labourer: watchman, doorman, servant, bartender, waiter, concierge and entertainer working in any kind of office, inn, hotel, cafe, dancehall, casino and bathhouse; veterinarian and chemist. (Hülya Demir and Rıdvan Akar İstanbul’un Son Sürgünleri [The last refugees from Istanbul], p.80, 1999, Belge Yayınları: Istanbul in Yahya Koçoğlu, Azınlık Gençleri Anlatıyor [Minority youths speak] p. 15-6, 2001, Metis: Istanbul.) Other attempts to nationalise the economy included the arbitrary dismissal of civil servants of non-Muslim origin in 1920s (The 1926 law has set ‘being Turkish’ a prerequisite for civil service employment, and that conditionality was going to be amended as ‘being a Turkish citizen’ in 1965), and the failed attempt to dismiss non-Muslim lawyers from Istanbul Bar Association in 1938 (Koçoğlu 2001:16-7).

15 Cinzia Braggiotti states that the law did not apply to the tradesmen in Izmir. (Böke and Daskan, 2011, February 5. Personal interview).

16 Ingrid Braggiotti states that he married to his father Charles Micaleff’s Aunt Marie and the couple had two kids: Giovanni, who moved to and passed away in Rome in 2002, and Teresa, who married Giovanni Reggio and still lives in Izmir.

17 Enrichetta Micaleff informed us that Maro Tito was Maria Rita Epik’s aunt, and she had married an American gentleman and moved to the USA.

18 E.M. stated that she was a Turkish citizen and her father had been a bank manager.

19 Harfuş’s husband had also been a bank manager, and the couple was from Syria. They had a son: Cem Bakioğlu. E.M. also mentions Pol Bakioğlu from St. Joseph College, whose mother was also a Syrian lady. They were Christian Arabs, probably Maronites. She also remembers that those families spoke mainly Arabic.

20 Mr. Paradiso had two sons named Giuseppe and Remo. Remo had a daughter called Gianna, and a son called Elvio. Giuseppe had two daughters called Paula and Carla. Paula is married to Ingrid’s brother Alex Micaleff.

21 The Giudicis are a Genoese family which moved from Chios, where they had initially moved to in the 1400s, to various spots in Turkey including Izmir, probably in the 1800s (Willy Sperco, Les Anciennes familles Italiennes de Turquie, 1937, Istanbul: Zelic) The oldest Giudici in Izmir Gürsoy (1993:266) could trace back was François Giudici (b. 1872) who founded an insurance company in 1891, called ‘Giudici & Son’. He is also noted to be the chairman of ‘Smyrna Insurers Association’ at the time. His son Hubert Giudici was going to be the agent of a big European insurance company as well as serve as an adviser in the ‘Italian Chamber of Commerce’. One of our previous interviewees, Pierino Braggiotti, has noted that his maternal grandfather Nicola Giudici (1856-1936; son of Constantino Giudici) was the commercial agent of a Swiss insurance company called L’Urbaine in Izmir (Böke and Daşkan, ibid.) The probable connection between Nicola and François Giudici needs to be clarified.

22 Jeanneau Zakari’s wife.

23 Franco-Chiotika.

24 By that she means that, as I.B. suggests, their knowledge of formal Greek ‘Katharevousa’ is limited.

To view the ancestral chart 3 generations back of Enrichetta Micaleff (née Triches) click here and to view her late husband Charles Micaleff’s ancestors click here:

Interview conducted by Görkem Daşkan and Virna Mulino on 21 July 2011, Izmir.

Transcription by Virna Mulino and translation into English by Görkem Daskan, August 2011.

Unfortunately Enrichetta Micaleff died on 5 November 2023, aged 99, in Izmir. May she rest in peace.

submission date 2011

submission date 2011

2 Oriental Carpet, İzmir Pamuk Mensucat, İzmir Basma and İzmir Yün Mensucat factories/companies can be listed among the enterprises led by the Girauds.

3 Today Kıbrıs Şehitleri St.

4 Enrichetta Micaleff’s daughter Ingrid Braggiotti who was also present at the interview.

5 I.B. states that Paradiso had been active until the mid 1970s. The baker’s shop that faces the school building still stands in the same location.

6 She was married Joe Clarke, E.M. states.

7 He currently works at Izmir St. Joseph College.

8 I Promessi Sposi (1827) in Italian: one of the leading novels of the Italian literature.

9 There have been enactments in 1924 and 1935 in Turkey, concerning the compulsory dress codes in public and private education institutions, which were in line with the secularisation movement, and the ban on the wearing of religious symbols at school was related to that.

10 According to Ingrid Braggiotti, he passed away in 1960, and his wife and kids withdrew from the partnership. Mr. And Mrs. Ragusin’s daughter Odetta is married to Maurizio Braggiotti and lives in Izmir. Their sons Gianni and Mariano (Rino) live in Izmir and are in the rubber business. Their youngest daughter Alba is married to Erdel Vidori and lives in the USA today.

11 I.B. states that he was related to the Whitall family. During an occupational accident, he got injured on his eye and had to change job, so he opened up a flower shop on Mesudiye/Kıbrıs Şehitleri St. and was also an occasional funeral undertaker.

12 Gürsoy (1993:257) states that Capadona had been very active mainly in the period between 1958 and 1963.

13 The Twelve Islands.

14 According to law no. 2007 enacted on June 1, 1932, those who lived in Turkey and were not Turkish citizens were not allowed to do the following professions: shoemaker, musician, photographer; barber, typesetter, broker, midwife; suit/dress, cap and shoe manufacturer; stock market purchaser, seller of monopoly products (i.e. tobacco and alcohol), interpreter and tourist guide; worker in construction, steel and wood industries; worker in water, lightning, heating, and communication works; driver and assistant driver, shipment worker, all kinds of labourer: watchman, doorman, servant, bartender, waiter, concierge and entertainer working in any kind of office, inn, hotel, cafe, dancehall, casino and bathhouse; veterinarian and chemist. (Hülya Demir and Rıdvan Akar İstanbul’un Son Sürgünleri [The last refugees from Istanbul], p.80, 1999, Belge Yayınları: Istanbul in Yahya Koçoğlu, Azınlık Gençleri Anlatıyor [Minority youths speak] p. 15-6, 2001, Metis: Istanbul.) Other attempts to nationalise the economy included the arbitrary dismissal of civil servants of non-Muslim origin in 1920s (The 1926 law has set ‘being Turkish’ a prerequisite for civil service employment, and that conditionality was going to be amended as ‘being a Turkish citizen’ in 1965), and the failed attempt to dismiss non-Muslim lawyers from Istanbul Bar Association in 1938 (Koçoğlu 2001:16-7).

15 Cinzia Braggiotti states that the law did not apply to the tradesmen in Izmir. (Böke and Daskan, 2011, February 5. Personal interview).

16 Ingrid Braggiotti states that he married to his father Charles Micaleff’s Aunt Marie and the couple had two kids: Giovanni, who moved to and passed away in Rome in 2002, and Teresa, who married Giovanni Reggio and still lives in Izmir.

17 Enrichetta Micaleff informed us that Maro Tito was Maria Rita Epik’s aunt, and she had married an American gentleman and moved to the USA.

18 E.M. stated that she was a Turkish citizen and her father had been a bank manager.

19 Harfuş’s husband had also been a bank manager, and the couple was from Syria. They had a son: Cem Bakioğlu. E.M. also mentions Pol Bakioğlu from St. Joseph College, whose mother was also a Syrian lady. They were Christian Arabs, probably Maronites. She also remembers that those families spoke mainly Arabic.

20 Mr. Paradiso had two sons named Giuseppe and Remo. Remo had a daughter called Gianna, and a son called Elvio. Giuseppe had two daughters called Paula and Carla. Paula is married to Ingrid’s brother Alex Micaleff.

21 The Giudicis are a Genoese family which moved from Chios, where they had initially moved to in the 1400s, to various spots in Turkey including Izmir, probably in the 1800s (Willy Sperco, Les Anciennes familles Italiennes de Turquie, 1937, Istanbul: Zelic) The oldest Giudici in Izmir Gürsoy (1993:266) could trace back was François Giudici (b. 1872) who founded an insurance company in 1891, called ‘Giudici & Son’. He is also noted to be the chairman of ‘Smyrna Insurers Association’ at the time. His son Hubert Giudici was going to be the agent of a big European insurance company as well as serve as an adviser in the ‘Italian Chamber of Commerce’. One of our previous interviewees, Pierino Braggiotti, has noted that his maternal grandfather Nicola Giudici (1856-1936; son of Constantino Giudici) was the commercial agent of a Swiss insurance company called L’Urbaine in Izmir (Böke and Daşkan, ibid.) The probable connection between Nicola and François Giudici needs to be clarified.

22 Jeanneau Zakari’s wife.

23 Franco-Chiotika.

24 By that she means that, as I.B. suggests, their knowledge of formal Greek ‘Katharevousa’ is limited.

To view the ancestral chart 3 generations back of Enrichetta Micaleff (née Triches) click here and to view her late husband Charles Micaleff’s ancestors click here:

Interview conducted by Görkem Daşkan and Virna Mulino on 21 July 2011, Izmir.

Transcription by Virna Mulino and translation into English by Görkem Daskan, August 2011.

Unfortunately Enrichetta Micaleff died on 5 November 2023, aged 99, in Izmir. May she rest in peace.

|

From left to right: Ingrid Braggiotti, Enrichetta Micaleff, Virna Mulino, Görkem Daşkan

Video segment of Enrichetta Micaleff speaking about the past