Rose Marie Caporal | Alessandro Pannuti | Ft Joe Buttigieg | Mary Lemma | Antoine ‘Toto’ Karakulak | Willie Buttigieg | Erika Lochner Hess | Maria Innes Filipuci | Catherine Filipuci | Harry Charnaud | Alfred A. Simes | Padre Stefano Negro | Giuseppe Herve Arcas | Filipu Faruggia | Mete Göktuğ | Graham Lee | Valerie Neild | Yolande Whittall | Robert Wilson | Osman Streater | Edward de Jongh | Daphne Manussis | Cynthia Hill | Chris Seaton | Andrew Mango | Robert C. Baker | Duncan Wallace QC | Dr Redvers ‘Red’ Cecil Warren | Nikolaos Karavias | Marianne Barker | Ümit Eser | Helen Lawrence | Alison Tubini Miner | Katherine Creon | Giovanni Scognamillo | Hakkı Sabancalı | Joyce Cully | Jeffrey Tucker | Yusuf Osman | Willem Daniels | Wendy Hilda James | Charles Blyth Holton | Andrew Malleson | Alex Baltazzi | Lorin Washburn | Tom Rees | Charlie Sarell | Müsemma Sabancıoğlu | Marie Anne Marandet | Hümeyra Birol Akkurt | Alain Giraud | Rev. Francis ‘Patrick’ Ashe | Fabio Tito | Pelin Böke | Antonio Cambi | Enrico Giustiniani | Chas Hill | Arthur ‘Mike’ Waring Roberts III | Angela Fry | Nadia Giraud | Roland Richichi | Joseph Murat | George Poulimenos | Bayne MacDougall | Mercia Mason-Fudim née Arcas | Eda Kaçar Özmutaf | Quentin Compton-Bishop | Elizabeth Knight | Charles F. Wilkinson | Antony Wynn | Anna Laysa Di Lernia | Pierino & Iolanda Braggiotti | Philip Mansel | Bernard d’Andria | Achilleas Chatziconstantinou | Enrichetta Micaleff | Enrico Aliotti Snr. | Patrick Grigsby | Anna Maria and Rinaldo Russo | Mehmet Yüce | Wallis Kidd | Jean-Pierre Giraud | Osman Öndeş | Jean François d’Andria | Betty McKernan | Frederick de Cramer | Emilio Levante | Jeanne Glennon LeComte | Jane Spooner | Richard Seivers | Frances Clegg

|

The

testimony below is an abridged version of the memoirs taken from the

family genealogical web site published by her son who interviewed her

before she died in 1963, aged 86. The material here was deemed to be

important because it crossed to an earlier generation of ‘Levantine

life’ pre 1922, and there are many illuminating sides like life in the

‘sticks’ of Sokia, as well as references to prominent families of the

time, such as the Pengelleys with whom the Lewis family are related

through marriage.

The web site was on line for a period during 2002-3, now offline, but the family were very helpful in both information and images, helping to compile this section.

MEMOIRS OF HELEN (LEWIS) LAWRENCE

Foreword

Helen (LEWIS) Lawrence died five days after Christmas in 1963. We had driven up from Long Island to visit her that Saturday preceding her eighty sixth birthday (which came on Monday, 18 November), taking her out to lunch, and later stopping to watch Bradley Smith star in his high school football game.

It was shortly after Thanksgiving that her heart weakened, and she realized that she would soon die. It is fortunate that she had gone to live with Dorothy and Ernie Smith in the comfortable apartment they had fixed for her above the doctor's offices, since she was able to receive the best of care from them. Her mind remained very clear. Her sons and their wives took turns nursing her, with Ralph and Elza shouldering the major part of the ordeal.

Lib and I had the opportunity to relieve them over a week-end in December, and thus for us to be with her for the last time. As her eldest child, I probably remember more about her family and our early life in Turkey. During her visits with us we spent many hours reminiscing, as I tried to recall events she remembered so well. I encouraged Mother to write these memoirs. She started them at the age of 84, sometime in 1962. Lib typed out a first draft, which Mother then went over, correcting and adding additional facts as she remembered them. Lib then typed out a second draft.

I wish that there had been time to go over what turned out to be the final draft with Mother, since there are many interesting details on which she could have expanded. But rather than yield to the temptation to tamper with her manuscript, it has been left intact as she wrote it. Fifty mimeographed copies have been run off, enough for each of her descendants, plus a few extras for relatives.

Arthur Lewis Lawrence

Centre Island, Oyster Bay, New York, 18 November, 1966.

PART 1

I am now 84, in good health and have normal hearing and eyesight. I was born in Sokia, a village 70 miles south of Smyrna, now Izmir, in Turkey. My parents were British: William Buckner Lewis and Leila (Williamson). They had eleven children four boys and seven girls. The fourth child, I was born in 1877. My father was the only son of the Rev. William B. Lewis, who was the British chaplain of Smyrna for five years, from 1843-1848. Grandfather and Grandmother Lewis had come to Smyrna as missionaries to the Jews in 1832. They had three daughters, all older than father. My mother was the oldest of 16 children of William and Lizzy Williamson of York, England. My father’s business in Sokia was managing a large concern that bought wild liquorice root from the peasants and extracted the juice and made it into paste. The extract is used in processing tobacco.

Note:

The web site was on line for a period during 2002-3, now offline, but the family were very helpful in both information and images, helping to compile this section.

MEMOIRS OF HELEN (LEWIS) LAWRENCE

Foreword

Helen (LEWIS) Lawrence died five days after Christmas in 1963. We had driven up from Long Island to visit her that Saturday preceding her eighty sixth birthday (which came on Monday, 18 November), taking her out to lunch, and later stopping to watch Bradley Smith star in his high school football game.

It was shortly after Thanksgiving that her heart weakened, and she realized that she would soon die. It is fortunate that she had gone to live with Dorothy and Ernie Smith in the comfortable apartment they had fixed for her above the doctor's offices, since she was able to receive the best of care from them. Her mind remained very clear. Her sons and their wives took turns nursing her, with Ralph and Elza shouldering the major part of the ordeal.

Lib and I had the opportunity to relieve them over a week-end in December, and thus for us to be with her for the last time. As her eldest child, I probably remember more about her family and our early life in Turkey. During her visits with us we spent many hours reminiscing, as I tried to recall events she remembered so well. I encouraged Mother to write these memoirs. She started them at the age of 84, sometime in 1962. Lib typed out a first draft, which Mother then went over, correcting and adding additional facts as she remembered them. Lib then typed out a second draft.

I wish that there had been time to go over what turned out to be the final draft with Mother, since there are many interesting details on which she could have expanded. But rather than yield to the temptation to tamper with her manuscript, it has been left intact as she wrote it. Fifty mimeographed copies have been run off, enough for each of her descendants, plus a few extras for relatives.

Arthur Lewis Lawrence

Centre Island, Oyster Bay, New York, 18 November, 1966.

PART 1

I am now 84, in good health and have normal hearing and eyesight. I was born in Sokia, a village 70 miles south of Smyrna, now Izmir, in Turkey. My parents were British: William Buckner Lewis and Leila (Williamson). They had eleven children four boys and seven girls. The fourth child, I was born in 1877. My father was the only son of the Rev. William B. Lewis, who was the British chaplain of Smyrna for five years, from 1843-1848. Grandfather and Grandmother Lewis had come to Smyrna as missionaries to the Jews in 1832. They had three daughters, all older than father. My mother was the oldest of 16 children of William and Lizzy Williamson of York, England. My father’s business in Sokia was managing a large concern that bought wild liquorice root from the peasants and extracted the juice and made it into paste. The extract is used in processing tobacco.

Note:

The liquorice concern was

McAndrews and Forbes whose Sokia [Söke] factory operated for about

a 100 years well into the 1950s. Five years after the arrival of W.B.

Lewis senior, the couple lost an infant child (6th) as seen in the Buca

cemetery, and from the headstone we thus know the name of his wife,

Margaret Elizabeth L. The Buca cemetery is also where William (1827-81)

and Elizabeth ‘Lizzy’ Williamson (1832-1919) are buried as well as well

as 5 of their children (4 of whom died in infancy). It’s more than likely

that Grace Edith W. buried in Bornova (1875-1945) was of the same progeny

and was the lady who ran the pension in Alsancak. Neither of the W.B.

Lewises are buried in the Smyrna cemeteries however there is a record

of Leila Lewis nee Williamson (1852-1936) in Bornova cemetery who was

the mother of Helen.

Life in Sokia was very different from life in an American village. We were the only English family there. Half the villagers were Turkish and the rest Greeks; they both had their own schools. We had a governess to teach us. The boys were sent to school in England when they were old enough. Naturally, we had no playmates, but our family life was a very happy one. When I was about four, I spoke only Greek as our servants and nursemaids were Greek. At that time the railway did not come to Sokia, only to Belejik. That meant one must ride a horse from Belejik to Sokia, a distance of about 15 miles. Imagine an Irish girl from an orphanage in Ireland coming to a strange country and being met by our Greek man servant, who put her on a horse and loaded her baggage on his horse and led her for 15 miles. I have a faint picture of her arriving. She had a lot of character and soon we were under her thumb. Her name was Kate Kelly and she was with us for many years. We had to behave, and she taught us how to sew, knit, and crochet. Also, we had lessons in reading and writing with her. She had full charge of us and we had our meals in the nursery with her.

We lived in a large two story house. There were four big chimneys, as the rooms all had fireplaces. Storks built their nests on top of the chimneys. They went south in winter and came to Turkey about the 25th of March, my older sister Maggie’s birthday, and they left to fly south the 10th of August on my sister Tottie’s birthday. (Her real name is Mary.) They raised a family of two or three. Storks have long legs and a long neck and beak, as they feed on fish, eels, frogs and anything they can find in swamps and shallow ponds. They always clapped their beaks when they go to their nests. It was a funny noise. It is well they were not there in winter, as the smoke from our fires would not be pleasant.

Our manservant’s name was Yani, the cook was Marigo and the housemaid was named Stasia. Once in two weeks the washerwoman, Katerina, came to wash the clothes. The wash-house was one of a row of out-houses. There was the servant’s bedroom, then Yani’s bedroom, the wash-house and the woodshed. The servants helped wash the clothes. There were two wooden troughs on a stone platform and the boiler next to that. The wash took two days to do, as after washing the clothes, they were spread in a round basket four feet across and four feet high, lined with sailcloth. After the clothes were laid out and the basket was full, they covered them with heavy sailcloth and put the wood ashes on top, then poured boiling water over that and left them all night. They next day they were soaped again and rinsed. Such a job, but the clothes were white as snow.

All our clothes were sewn at home and as the style was then, we wore chemise, slips and panties that buttoned on a little bodice. We never wore anything that was not made at home. To keep eleven children dressed was a lot of work. Even my father’s and the boys’ suits were made at home. We even made our own soap.

We had a large garden, a barn and chicken yard, and all our property was surrounded by a 10-foot high wall with a large gate which was locked at night. Since we were the only English family and our parents were anxious to bring us up properly, we never mixed much with the native children. We had very few toys and only rag dolls. We played games and had our own flower gardens and were very happy.

My father’s sister, Arabella, married a sea captain named Pengelley. Their home was in Cardiff, Wales. They had a large family. Two of their sons, my first cousins, named Alfred and Rowley, came to Sokia when they finished schooling, to work as accountants in the liquorice factory. Rowley brought his bicycle, which had a big wheel and a small one. When he rode it, crowds of children ran after him to see it.

Alfred married Nellie and Rowley, Becky, both mother’s sisters.

Note: From a headstone in Buca cemetery of one of their infant children we are able to discern the name of this original Pengelley as Commander Walter Murray, married to Arabella Sarina P. Many of this family are buried in Bornova, Alfred W. (1856-1928), Ellen ‘Nellie’ (1868-1934), Rowland A. ‘Rowley’ (1861-1933) and Rebecca M. ‘Becky’ (1859-1936).

Father was very kind to the natives and gave them quinine for malaria; he had a set of forceps and he would pull out their bad teeth. He also gave them lotion drops for their sore eyes and he was their lawyer and counsellor, as well. They used to say that he would give “the shirt off his back” to help them. He died in 1903, after an operation for stones in the bladder.

Every summer we went to the seaside. We had to take bedding, dishes, silver and provisions for three weeks. We slept on cotton quilts but we took mattresses and pillows for the older people. All this was loaded on camels, and they left in the evening. We left on horses early next morning. When we got to the beach, we had to find a house to rent and the servants had to clean it so we could move in. It was an awful lot of work, but we were very healthy.

Getting shoes for the family was a big job. A shoemaker came to the house and took our measurements and a week or two later brought them for us to try them on and see if they fit us. Our stockings and socks were knitted for us. I learned how to knit stockings when I was nine. I also made crochet edging for my slips and pants. I was always a very poor student but I loved dressing our rag dolls and sewing my underclothes. When I was 13, I bought material and made a dress for a poor girl friend. We could not buy patterns in those times. We made our own patterns.

I loved horse back riding. We had a fig orchard a mile and a half away. The Turkish caretaker and his family lived there and dried the figs. Every morning one of us children went there on horseback and filled a basket of delicious ripe figs for us to eat at breakfast. Many a morning I rode there at sunrise and climbed the fig trees and filled the basket. Often in my dreams, I have been there again, and awake to find it was only a dream.

The country around Sokia was hilly and so beautiful and we all went on long walks together. On Sunday afternoons Father and Mother came with us and we were dressed in our Sunday best. White muslin, starched dresses with a wide sash of ribbon around the waist, tied in a big bow behind. My father conducted an Episcopal service on Sunday morning in our parlor and all the family attended. I played the piano for the hymns and he read a sermon, usually out of a magazine called, “Sunday at Home”.

We always had company staying with us: aunts, uncles, cousins, Neneka, our Nana and friends. Sokia was now at the end of the railway, a branch line of the Aidin railway, from Smyrna. Many times people who were going to see the ancient ruins of the towns of Pyrene and Myletus had to come to Sokia. They had to stay overnight and hire horses to ride to the ruins. So our home was open to them. I remember when Sanky and Moody, the great evangelists, went to visit the ruins at Pyrene. They stayed with us and we had a service and two of our youngest sisters were christened by them. Father never missed daily family prayers with all the family and servants attending. He read the Bible through to us many times. Father and mother never started the day without kneeling down together at the sofa in their bedroom and praying. I have a vivid picture of them. We would try and be quiet while they were praying. Such a wonderful mother we had. I adored her and would do anything for her. She had beautiful curly, auburn hair and lovely brown eyes and white, white complexion. She was only 19 when she got married and Father was 28.

We always had plenty of books to read. As we grew older, Kate Kelly went to work for a family in Istanbul. We had a governess to teach us and somehow we got educated enough in the three R’s. In winter we had fires in the fireplaces and in the evening we all sat around with our fancy work or sewing and Mother read aloud the classical books and all of Dicken’s novels. Mother had a very lovely reading voice. I sure am lucky to have had such a wonderful home life.

As we grew older we visited friends and cousins in Smyrna. There were two lovely English ladies who came to Smyrna about 1892 or 3. They were social workers and were sent to Smyrna to work at the Smyrna Sailor’s Rest. Mr. Bliss who was the owner of the liquorice business in Turkey, fell in love and married the older sister. They had a lovely home at Sokia, where they lived a few months every year. The younger sister was visiting her sister, the summer I was 13. She had a Bible class for us girls. My mother’s youngest sister Alithea was visiting us then also. This lady had great influence on me. I stayed after class and she prayed with me and I was converted. Ruth, my youngest sister, was born April 15, 1892. She was such a beautiful baby and looked like my mother. When the first World War started in 1914, she went to Egypt with Dorothy, who was three years older. Ruth worked as a nurse in the British Army Hospital in Alexandria and Dorothy went to Malay to keep house for Jack, our brother, who was an engineer on the British Railways. She met Jim Latimer and they were married in 1917 and her twins, Peggy and Neil, were born in 1918. (Uncle Jim was a mining engineer for the Malay copper interests.)

At 17 I went to be a governess with a family in Smyrna. At 19 I taught at the American Mission School for girls in Smyrna. The American Mission School for boys was a few blocks away. Clara Lawrence was teaching at the girls school and she influenced her brother Caleb to come and teach in the boys school in 1896. He was 28 then. The teachers all had afternoon tea together and Caleb was often there to be with his sister. That is how we met and were engaged, that winter 1897. The summer of 1897 we spent at Patmos. It is a beautiful island very near the coast of Turkey. Now, when I look back at that trip, I realize what a tremendous undertaking it was, as we always had to take bedding and provisions. Caleb and cousin Harry Pengelley came with us, also, two servants. The camels took our things to a place called Spelia on the coast, 30 miles from Sokia. We followed on horseback. Remember there were no telephones or mails or even telegraph service then. At Spelia we had to hire a sailboat large enough to take us and our baggage to Patmos. It would take seven hours with a brisk wind. But we were becalmed and it took 17 hours. We were all seasick as the boat rocked back and forth in the blazing sun. When we finally got to Patmos, we were well repaid for our trouble. We found two cottages on the cleanest, clearest beach. The sea was always calm and we hired a small sail boat for the season, and we would go to picnics to other parts of the Island. The only town was on a hill and the houses were built around a monastery that was 800 years old. There were many old books in the monastery written on parchment and several very ancient vestments. Patmos is the isle where St. John the Divine wrote the Book of the Revelations. There was a cave near the monastery where he is supposed to have lived and had the visions. I did not teach at the American School that fall, but stayed home. Caleb and I wanted to get married but my father and mother thought that we should wait till Caleb was getting a better salary.

In the summer of 1899, Aunt Grace, my mother’s sister, was going to England to train as a nurse. Aunt Alithea, mother’s youngest sister and my older sister Maggie, who were the same age, were in England training at the Staffordshire Royal Infirmary. So I decided to go to England with Aunt Grace to train. We travelled together, going by sea on a cargo steamer. Fortunately the voyage was very calm and we enjoyed it. Aunt Grace and I started our training at the Derbyshire Royal Infirmary. But we both found the work too hard. Aunt Grace got T.B. and returned to Smyrna on a cargo steamer, which did her a lot of good. Neneka, her mother, was a natural born nurse and gave Aunt Grace the care she needed. She was cured and a few years later went back to England and trained as a midwife in London. She was in charge of the British Seaman’s Hospital in Smyrna for many years.

I went to a small hospital from Derby. It was the Longton Cottage Hospital in Staffordshire. It seems to me now when I look back to those years at Longton that I learned a lot more there than just nursing. The Averill family befriended me and treated me like one of their family. Their father was a visiting doctor at the Hospital. His five daughters became like my own sisters. My brother Alfred, who was going to South Africa to fight in the Boer War, came to Longton to visit me before he left. The Averills were very good to me too, and he fell in love with Nancy, who was my age. After Alfred left he and Nancy corresponded. After ten years, Nancy went to Africa and they were married at Broken Hill in Northern Rhodesia. Alfred was in charge of a copper mine there. When I finished my training in Longton, I went to the Sheffield Royal Infirmary. That year Queen Victoria died and all England was in deep mourning. It was a very big hospital and I had a good training there. It was a four-year course, but in January 1904, after I had been there three and a half years, Caleb wrote to say that the Boys School in Smyrna was now a college and he was professor of English and History and getting a better salary and we could get married. I had only a half year to become a registered nurse but I was now 27; really twenty-six and a half and I felt I had enough training. I decided to go home and we would be married in July, when the college had summer vacation.

My father had died the year before and my mother with my five younger sisters: Mary, Ethel Louisa, Dorothy and Ruth had gone to Tanta, Egypt, to live with Purdon, my older brother, who was in business in Egypt. My oldest brother William was also in Southern Egypt. My sister Mary did not live in Tanta with us, as she was superintendent of a Greek hospital in Alexandria. Ethel, also, was training as a nurse at the Presbyterian Mission Hospital in Tanta.

I arrived in Alexandria in March 1904, after a very stormy passage on a cargo steamer. Mary met me in Alexandria and nearly had a fit when she saw how thin I was. The voyage took a month and I was seasick all the way. We all started sewing my trousseau under mother’s supervision. My wedding dress and going away dress, were ordered from England. It was most exciting. Caleb arrived the end of June and the wedding was July 6th. Maggie was nursing at a hospital in Beirut and got her vacation so as to come to the wedding. I was the only girl in our family to be married from home and Purdon the only one of the boys, three years later. The marriage was in the Presbyterian Mission Church.

The American Consul from Cairo had to witness the marriage, so as to make it legal. He was to arrive at 10 o’clock that morning on the train from Cairo. Purdon went to meet him and we were all in the church waiting. Somehow Purdon got to the station a few minutes after the train arrived and the Consul got a cab and went to the Presbyterian Hospital, thinking the Church would be there. But, it was not anywhere near there. Purdon got back to the Church and said that the Consul had not come. I began to cry, as we had booked our passage on the boat leaving Alexandria for Greece that evening. Just then he turned up and we were married and we all drove home for a party and wedding cake.

We left for Alexandria at 1:30 and our trunks were supposed to leave on the same train. But they did not. We were told to go on board the steamer and the trunks would come on the next train and would be sent on board. It was almost time for the boat to leave and they had not come. I was awfully worried, as all my wedding presents and lovely clothes were in them. They arrived in time. In fact, the boat waited for them to be brought on board. I was not seasick because the sea was very calm.

We had a glorious two weeks in Greece. We stayed at a hotel in a fashionable resort called Kephessia. My mother’s sister, Bella Thorman Anderson, lived in Athens and we visited her for a few days. I have a picture taken in her garden. Caleb had a beard then. Her two lovely daughters, Laura and Daisy, were in their teens.

During our first year of marriage we lived in the College Main Building on Miles Street. Mother and the girls all left Tanta and came back to Smyrna. They lived in Boudjah, a suburb of Smyrna, where many British and French families lived. Ruth was 12 and Dorothy was 15 and went to an English school for girls in Boudjah. Ethel stayed on in Tanta to finish her nurses training, and Mary was nursing in Athens. Maggie was back at the hospital in Beirut. Aunt Grace was at the British Seaman’s Hospital at the Point in Smyrna. My oldest brother William was Sexton at St. John’s Church at the Point. Arthur was born in the British Seaman’s Hospital on the 8th of May, 1905. My joy and pride is indescribable. I stayed awake to listen and see if he were breathing while he slept. A healthier, lovelier baby never lived. Caleb called him “a tickling surprise”.

When we first returned to Smyrna after our honeymoon, Caleb had to go to Ephesus and the other six original Christian churches to take pictures for a Mr. Giles, who paid him to do it. Caleb’s sister Clara was living with us then. Caleb was very interested in antiquities and gave many lectures on the Seven Churches and had pictures and slides made from the photographs he took. All his evenings, he spent studying as he was taking a course at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, by correspondence. He graduated and got his M.A. in 1909.

Summer in Smyrna was very hot so the missionaries used to go to the seaside at Fokia [Foça] or the mountains at Boz Dagh. The summer Arthur was a year and a half, we spent up at Boz Dagh. At that time there was a renowned brigand called Charkirge. He was a sort of Robin Hood and had a band of followers. When they needed money they would take a rich man as hostage and demand a ransom for him. He lived in the village where we were spending the summer. We found this out after we were settled there. We were quite a large group, as the Scotch Missionaries to the Jews were with our group of missionaries. Charkirge’s wife had just had a baby girl and he did want a boy. I was told he had his eye on Arthur and I was so afraid. Mrs. Caldwell and I decided to go and visit his wife and take her a gift which we did. Also, we decided to have a picnic and invite Charkirge and his men to come to the picnic. We had a golf course that the men in our group made and we often took our evening meal and had it out there. This picnic was to be a sort of party, and each family made something extra good. One of the ladies had a camera strung over her shoulder and when Charkirge arrived they took it from her, as he was afraid of having his picture in the papers. The government was trying to catch him and had posted a sum on his head. The picnic went off very well, and the next week he returned the invitation. They had a lamb roasting on a spit in front of a wood fire out near our golf course. We all went and had roast lamb, pilaf, yogurt and Kadaif (a sweet). We had a more comfortable feeling now we were friends. Aunt Louisa was with me, also our Greek servant. It was a lovely spot--a sort of plateau almost at the top of Mt. Boz Dagh. The blackberries were thick there and we made several five gallon cans of jam. They tasted like wild black raspberries.

That year we lived in a rented house near the College and the rats were terrible. Caleb wrote a book while we lived there. It did not sell unfortunately.

The Caldwells lived in a house that the College owned, next to the College. The College and the Mission owned all the best houses in Smyrna at that time. Miles Street was, or had been the largest, widest street of Smyrna. However, the French Quay Company that built the Quay also built many houses on the Quay and it soon became the fashionable quarter [Bella Vista?]. The Caldwells had their first furlough in 1907, so we moved into their house that summer. Edward was born that year on September 15, 1907 at the British Seaman’s Hospital. The stork started coming at 2 in the morning and Caleb had to go and hunt up a cab to take me to the hospital. It was quite a race to get to the hospital in time. The cab was old and the horses half asleep.

My brother Purdon’s wedding was that week and I was very disappointed that I could not go. Edward came two weeks before we expected him. Purdon married Mabel Wilkin, our first cousin. She is three weeks younger than I am. Purdon’s business was in Egypt. He was a contractor for dredging the Suez Canal and they lived in Ismalise. Kenneth was their first child and Mary next, then Leila.

Note: The church records of Buca baptisms records this and other details; in 1908 Kenneth Purdon son of Mabel Louisa and Richard Purdon Lewis, civil engineer in Ismaila, Egypt.

Kenneth was in the Royal Air Force and during the Second World War he trained the Polish young men who escaped to England into a fine Polish Air Force. He is retired now. He has two sons and a lovely wife. Mary is also a good business woman. Purdon died of cancer in 1941. Mary, who had worked in her father’s office, carried on his business. When the Italians began to drop bombs on the British troops in Egypt during the 2nd World War, Mary sold the business and went to South Africa with her mother. Her sister Leila was in charge of a children’s concentration camp in Alexandria. Mary worked as a stenographer in Rhodesia and married and has a little girl. Mabel is living in Rhodesia with Mary.

In June 1908, when Edward was 10 months old, Caleb had his furlough and we went to Kingston, Ontario, as he was to be at Queens University for his last year. He had done three years work by correspondence and studied French too. We had rooms with an English lady but it was very hard for me, as Ed was just a year old and very active. Caleb’s sister Ophie found an apartment for me and the boys on the ground floor, so in March 1909, I went to Elyria, Ohio, and Caleb remained in Kingston till he graduated in June. Lake Ontario was frozen over and we drove across the lake in a open sleigh drawn by two horses. The ice was thawing and cracking. It was a frightening ride. Caleb went with us to Oswego and put us on the train for Elyria, Ohio. He was the poet of his class and had the highest honours in his class.

We spent the summer in Elyria and returned to Turkey in August. Nancy Averill used to write to me. Her mother and father had died so I asked her to come to Smyrna and live with me. My cousin, Alfred Pengelley, who married my mother’s sister, Nellie, had been to England that summer, so we arranged that Nancy should travel with them when they returned. We lived in a very nice big house that the College bought and had a nice bathroom made in it for us. It was also on Miles Street near the college. Alfred was born in that house on April 27th, 1910. I was so sure I would have a girl this time. I did want a daughter. That year Doreen was born to Ethel, and Tottie, who was married and lived in Broken Hill in Northern Rhodesia, had a lovely baby boy. He died when two years old.

Dr. MacLachlan, the President of International College, was in America that year and Mrs. Kennedy gave him about half a million dollars to build the college out at Paradise, which was two and a half miles outside of Smyrna.

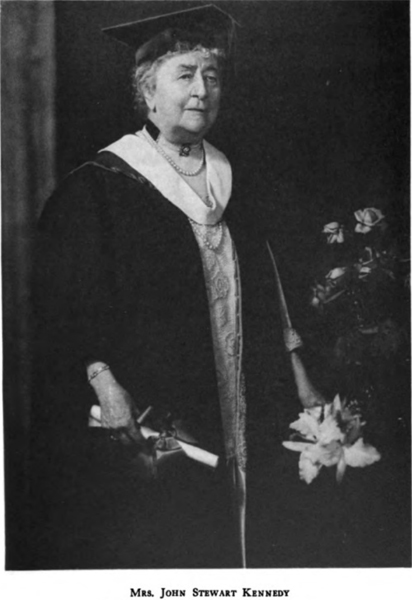

Note: Information courtesy of Helen Lawrence’s grandson Michael Smith: The wealthy benefactor was John Steward Kennedy, a central figure in New York banking circles around the turn of the century. When he died in 1909, he left $30 million to various charities, including $10,000 to the Boy School in Smyrna. John Kennedy was also on the board of trustees of Roberts College in Istanbul. He and his wife were apparently active with the Protestant Missionaries. After Mr Kennedy died, his wife continued to send my grandmother a cheque every month to help with the bills while they were in Smyrna - a letter from 1925:

The Boudja train stopped at Paradise. Through the College, the Caldwells and we were able to buy a plot of land each, next to each other. The Caldwells adjoined the college campus. We each had half an acre and we built houses more or less alike facing the street that led to the college. We both had lovely gardens.

Note: It seems likely these buildings stood where the NATO ‘motor pool’ now stands facing the college grounds, thus possibly destroyed in the 1950s.

We moved into our houses in 1912 but the college did not move out there until 1913. We lived there for 20 years, a life of wonderful experiences, friendships and joys. We had such wonderful friends. The Ralph Harlows came to teach in the college that year. We had been in our house a month when Henry was born on October 25, 1912. The summer of 1911 cholera broke out in Smyrna, so Caleb and I with our 3 boys and Mr. Montisanto and his two children went to Metiline, an island not far from the coast of Turkey. All the children got the mumps there, and so did I. Caleb was somehow immune to fevers and was very healthy. Alfred was one and a half and a lovely baby with curly red hair. He was my first red head. Nancy Averill only stayed a year with us, and a year later went to South Africa and was married to my brother, Alfred. Reggie was born to them in Africa and two years later, in 1915, Alfred took her to England where Johnny was born. Alfred left her in England while he went to North Dakota to work for William Simpson, Maggie’s husband, on a farm. Nancy followed that fall.

PART 2 - Paradise or Kızılçullu

Our house at Paradise [Kızılçullu–Şirinyer] was started in June, 1912, and was finished so that we could move in during the first week in September. The Caldwells’ house was next to ours and both houses faced the street that went to the college. We each had an acre of land. There were ten apricot trees along the northwest wall of our property. We engaged a very good gardener to dig out all the witch grass and lay out the garden. On the southeast side of the house and the front, we had flowerbeds, and from the end of the house all the way back was a wide path, ending in a circular court, with plane trees all around for us to sit under. We had many parties there.

We had lavender hedges on either side of the walk from the house; they grew three feet tall and a foot wide. We raised our own vegetables and had a nice strawberry bed at one time. We had our own well and a windmill, which pumped water into a large tank in the attic for use in the house, and for running water. There was an above-ground cistern in the garden, called a havousa [havuz is Turkish for pool]. It was round and about five feet deep and two yards in diameter. We used the water to irrigate the vegetable garden and had hand watering cans to water the flowerbeds. The boys used to bathe in the havousa. We had bamboo canes growing all around, so that it was quite private. We had plum trees, fig trees, pomegranate, and Japan apples, besides the apricot trees. Also, two lovely pepper trees in front of the house. How things grew there! The garden walks were paved with gravel, as it never rained from May to October and no grass could grow.

On our first Christmas day there we had a pine tree for our Christmas tree, with the roots in a ball. We planted it the day after Christmas and it grew into a giant tree. Henry was born on Founder’s Day--October 25th. We had a Greek servant then that we brought from Mytiline the summer we were there. Her name was Zaharo. She had a daughter who was 12, and we had her with us, too. Her name was Pelaghier. They went back to Mytiline when the First World War started.

In October 1913, when Alfred was three, he was given a big football to kick, by some of the college boys. The kick he gave, somehow broke his leg, just above the knee. The boys carried him in to Mother. I was holding Henry in one arm and took Alfred in my other arm. As I did so, I heard the bones cracking and realized he had broken his leg. So kept him quiet with leg straight and sent someone to Boudjah for Dr. Lorando, the college physician. He put on a temporary splint, and the next day Dr. Chassaud came with my sister Dorothy, who was training as a nurse at the B. S. Hospital. They put it in a plaster cast and had an extension on, so the bones would not overlap and cause lameness.

Alfred was in so much discomfort and pain that he kept crying continually. I had not slept for five days and nights, nor had he. So I felt I was going out of my mind. Dorothy came and helped me, and got him quiet, so I could have a few hours sleep. People used to bring toys and books for Alfred. Soon, he got to expect a present every time anyone came to see how he was. He would ask me, “What did they bring me?” He was always such a cute little boy. Everyone adored him. Very much like Dot’s Cleighton.

The next February, 1914, I got pneumonia, but would be up and down and did not have a doctor. My temperature used to go very high every evening, so Caleb had me go in to Smyrna and see Dr. Chassaud. He weighed me and I had lost a lot of weight. He found a spot in my lung, which he said was T.B. and ordered me to go to bed. Dorothy came to look after me. My dishes were kept separate. Alfred was taken to stay with my Mother in Boudjah. Henry was a year and a half and a great cry-baby. Zaharo looked after him. Arthur and Edward were going to first English classes at the college. Arthur had been going to Miss Shakleton’s School in Boudjah, after we moved to Paradise, before the college moved out. I had to swallow raw eggs, and was supposed to have eight eggs a day and plenty of milk.

In May I went to Fokia (the favorite beach resort of the missionaries). Dorothy came with me and a servant and the four boys. We took camp beds, dishes and cooking utensils. There was a boat that went to Fokia from Smyrna once a week. When we got there, we rented a house and rented tables and chairs from a coffee house. It never rains in the summer, so we spent our days on the beach and I had to lie in the sun by the hour. After we were settled, Dorothy went back to the B.S. Hospital. The school closed the end of June and Caleb was to come and stay with us.

About the middle of June there was a rumour that the Turks from Macedonia were coming to Fokia to massacre the Greeks and take their houses. The war between Greece and Macedonia had ended. The Greeks had won and were getting all the Turks to leave. These refugee Turks came to Turkey with the idea that they would get the Greeks, who had lived in Turkey for hundreds of years, to get out so that they could move into their homes. Many Greeks were killed.

Fokia was inhabited by Greeks and we heard that a band of Turkish families was coming to Fokia to massacre the Greeks and take their houses. I wrote this to Caleb, but there was no boat from Smyrna to bring mail and take mail back. The regular boat had stopped. On the day that the Turks were to arrive, many of the Greeks left in open boats. They took what they could with them. They were going to the Greek island of Mytiline. Fortunately it was very calm, as they left in open rowboats.

The house we were in was not in the village and more or less isolated. I became nervous and wondered what I would do if there really was a massacre. We did not bring an American flag with us. Prayer helped me to be calm and I was not afraid. Caleb heard the rumour that there would be a massacre at Fokia. He asked Dr. MacLaughlan, the college president, what he thought and he seemed to think there was no truth in the rumour. But Caleb could not sleep and felt sure he should come for us. In fact, he woke up in the night and felt he heard a voice telling him to get up and go for me. He did, and he went and got Dorothy and Ruth, my youngest sister. They had to hire a tug boat, as the regular boat had stopped. They hired one from Herbert [James] Whittall [of C. Whittall & Co. 1884-1933, who married a Grace Pengelley] and came for us. The boys and I had walked up the hill where we could catch sight of the boat, we were so sure was coming for us--and it did come in mid-afternoon. It was flying the British Union Jack, so we knew it was Caleb. The boys ran to the landing wharf and as Caleb met them they said, “We were going to be murdered tonight!” Dorothy and Ruth helped pack our things and we were all on board and left by five P.M. It was about 11 when we got home.

We did not go anywhere that summer. In August the First World War started. The Germans were fighting against the French and British. Austria and all the Balkan States and Turkey were on the side of the Germans. All British men in Smyrna were interned and the entrance to Smyrna Bay was closed, so no ships could come in or go out. The British ships were outside the Bay and used to bombard Smyrna. It was an awful time, but the college was not bombed. Food was very scarce--no sugar, tea or coffee. By roasting figs to a crisp, then pounding them to a powder, we made coffee. We soaked raisins and pressed out all the juice, which we boiled into a syrup, making petmez. We used cracked wheat for cereal and we could get milk from a farmer near us. We sweetened food with petmez [pekmez].

Ralph was born in March 1916. A year later, when America was likely to fight on the side of Britain and France, all American women and children of the mission were advised to go to America. Mrs. Caldwell and I left for Constantinople with our children on March 16th, 1917. The way to get to America would be from Constantinople through the Balkan States to Vienna, where we would be interned for three weeks so that any information we had of our enemies would be of no use. The train took us as far as Panderma [Bandirma] on the sea of Marmara, where we would get a steamer for Constantinople. However, before we reached Panderma, an inspector checked our travel permits and found that the college dragoman had them made out for our husbands to come with us. The inspector was very angry and was going to have us get off at a siding in the middle of the night. A young Turk, who had been a student at the College, talked to the inspector and explained it was a mistake made by the dragoman. So we were allowed to go to Panderma and wait there for new permits to be sent from Smyrna. Mrs. Caldwell, with her four children, and I with five boys, waited five days in Panderma. Ralph had his first birthday there on March 20th.

When we got to Constantinople, we stayed at the Bible House until we got permits to go to Vienna. We had to take food to eat on the train for four days. We had hard-boiled eggs, bread, olives, halva and cheese, and a water jar. I had four suitcases besides the packages of food and a small alcohol stove to prepare the baby’s food. I was able to get cans of condensed milk. This was before evaporated milk or cans of condensed milk. I had a very small supply of diapers, so I used a little pot and held Ralph on it. Arthur and Edward carried two suitcases apiece. Alfred was not yet seven, and he had to carry the water jar and food. Henry was four and a half.

We left Constantinople on April 5th. The train was loaded with soldiers and hardly any civilians. The train compartments had two wood benches facing each other. We had one compartment, and with our suitcases we were quite crowded. Mrs. Caldwell was a great help, as I had the baby to hold most of the time. She rationed the food for each day and gave us each our share at meals. We had to change trains several times and had to stand in line to have our tickets and permits inspected at the ticket windows of the depots. The boys had the suitcases to carry and they had to be inspected at the different countries where we stopped.

Everything would be dumped out of the suitcases. We also had to step out of our shoes, to prove that we had no messages hidden in them. The inspectors looked in our pocket books and felt us all over.

At one stop, where we were not supposed to get off, we had the three oldest boys get off to fill our water jars at a fountain. The train started to move before the boys got back. I was frantic, as I had no idea where the train would stop next. After a few minutes the boys appeared. They ran and jumped on the last car and walked to our compartment.

At Nish in Servia, we had to wait all day for the next train. So we took a walk through some fields at the back of the depot. Some boys came and began throwing stones at us. We went back to the depot. Our train came in about 10 P.M. My boys had been sleeping. We had to dash out to get a compartment for ourselves. Henry was four and a half years old then. He was sound asleep and I could not wake him. I had Ralph to carry, so I dragged Henry along. As we crossed a mud puddle, he slipped from me into the mud.

That night, on the train, something was crawling on my back. I went to the toilet and stripped. It was a louse all right. They were carriers of typhus fever and I was afraid of getting it.

We changed our train in Hungary. The train compartment was large and there were seats on each side. The train made many stops, picking up people. I was so tired that I fell asleep holding Ralph, who was also asleep. Some of the women on the train began singing, and as I heard it I thought I was in Heaven. It was so beautiful and tears were rolling down my cheeks. But I woke up and realized where I was.

We arrived in Vienna early Easter morning. On April 7th the United States had broken off relations with Germany, to fight on the side of Britain and France. Mrs. Caldwell knew German, so we decided that she and Alice, her daughter who was 16, should take a cab and look for rooms at a hotel. They went to the American Embassy, but the Ambassador and his staff had left. They found an American who helped them, and they were able to get us rooms at a nice hotel. I waited in the waiting room of the station with the children, five of mine and three Caldwells.

It was 4 p.m. when Mrs. Caldwell came back. When we got to the hotel I had visions of getting my children into hot baths. However, on account of the war, there was no coal to heat water for baths. The hotel provided pitchers of hot water and a large wash bowl, so I washed them all and put them into bed. They had no supper but were asleep in no time. During those three days on the train no one was able to wash. There was no water except what we had in our jars. We wet a wash cloth that was passed around and then thrown away.

On the next morning we went down to the restaurant, but as we had not been issued ration cards, we could only get hot chocolate. Later, we went to the police station for ration cards and to find out where we would be interned, to wait until we would be free to go to Switzerland. We were sent to Laudeck in the Tyrol. The hotel we stayed at was nice and clean. Every day we had to report to the police. We could walk around, as long as we did not go more than a mile from the town limits. The food allowed on our ration cards was a bit skimpy for growing boys. A Greek lady, who also was interned at the same hotel, often saved her bread for the boys. On April 27th Alfred had his seventh birthday. Our hotel manager had the cook make a very nice cake, and we had a party.

After three weeks there, we were allowed to leave for Switzerland. It seemed so wonderful to be in a free country. We stayed in Bern, the capital. Mrs. Caldwell went to Zurich. At Bern I stayed at a hotel, and having five restless boys it was a constant worry lest they were being too noisy. Ralph had a high fever and I was so worried. We heard that a party of missionaries from Turkey was staying at another hotel. Dr. Ward from our mission was there, so I sent Arthur to ask him to come and see Ralph. He said he had malaria, and gave me quinine to give him. Ralph got well soon after.

We found a nice home-like inn, high up in a mountain village, called Gertzenzee. It provided an ideal life for the boys, and it made my life easier, waiting for Caleb to join us.

The American Consulate in Smyrna closed as soon as we joined forces with the Allies, and Caleb, who was working at the Consulate should have left with the Consul General and his staff. For some reason he did not, and had to go through the tedious performance in Constantinople of getting a permit to leave Turkey. The day he went to the passport office to get his permit to leave for America, there were two American men who, also, wanted permits to leave. They were employed by a tobacco company and were suspected of having protected some Armenians that were wanted by the Government. Their passports were taken away from them and my husband being with them, had his passport taken away too.

Two months passed before he was able to prove his innocence and get his passport back and a permit to leave. It was July and I had not heard from Caleb. I prayed and hoped.

After spending all of one night in prayer, I heard a knock on my door, very early in the morning. A messenger handed me a telegram. It read, “Arriving in Bern today at 8 A.M.” It was now five o’clock and the bus left at 6:30 A.M. It was quite a rush getting ready. I left the children in the care of a baby sitter. I walked into the depot in Bern just after the train arrived. What a loan of responsibility was lifted off my shoulders! Shortly after that we were able to leave for the United States, going through France, to the Port of Cherbourg.

Switzerland is a lovely place to live in. At the hotel in Gertzenzee, they often fixed sandwiches and picnic lunches and we would spend the day in the woods. I got the boys a low four-wheeled cart and Arthur used to go down the hill in a narrow path, like a whirlwind, and scare me to death. But fortunately, we were spared any broken bones or cuts. When Caleb came we really went mountain climbing a couple of times.

The German subs were attacking all ships, so our departure from Cherbourg was kept secret. We were not allowed any lights on board, so had to have meals by daylight. There were life boats assigned to each person and every day we drilled, so we would know which life boat to go to if we were torpedoed. We got to New York without a mishap and our dear friends, the Harlows, met us and invited us to stay with them in Brighton, Mass., until we found a house. We found a furnished house in Melrose at 19 Parker Street and we lived there for a year and a half.

MELROSE 1917-1919

Mr. Lord, the owner of the house we rented, was a widower. He had a sad life. They had a son who was in an insane asylum, and it broke his wife's heart when he died. She did not live long after that. His daughter married, but on her honeymoon she and her husband had an accident and their car was smashed on a railroad crossing by a train, and she had a bad injury for life.

The house was nicely furnished and had a coal furnace. We paid $35.00 a month rent. There was a good garden in back, with several fruit trees--lovely pears that were just ripe when we arrived. There was also a chicken coop that had not been used for some time. Arthur and Eddie cleaned it and whitewashed the walls and used it as a clubhouse. One of their school friends had polio and could not walk, so the boys helped push his wheel chair to school; he was a club member. Opposite us lived the Clisbys. He was a fireman and they had a little girl Ralph's age. They played together so nicely. We were very happy there.

But the First World War was still on and in November 1917, Caleb was asked to head the Foyer-des-Soldats (French Y.M.C.A. in France). He spoke French, so he went to France in December. He had registered for classes at Harvard, hoping to get his Ph.D. He was in the thick of things, often under fire and in grave danger. Once he and his French assistant had just crossed a bridge, when it was blown to pieces. Another time, when the Big Berthas were rather bad, they decided not to sleep in the Y headquarters. In the morning they found the place had been bombed and nothing left of it. But Caleb's quiet manner and sure confidence brought him through unscathed and made him a tower of strength to others.

One evening my phone rang and the operator said, “I have a cablegram from the War Office.” Oh! was I scared! I could not listen properly, as she read the cable. However, I realized it was not bad news. So asked to have it mailed to me. This is what it said, “Caleb Lawrence, acted with great bravery during the recent bombardment. Frenchmen warm in their praise of his conduct.”

My sister Louisa had gone to North Dakota before the war started and was living with our oldest sister, Maggie Simpson, on a farm. She did not like it there, and Caleb and I thought of asking her to come and live with me, while Caleb was in France.

In 1901 Aunt Maggie took Aunt Ethel to South Africa to marry Harry Pengelley, whose wife had died, leaving a baby girl, Kathleen. Harry lived in Kimberley with my brother Alfred and they both worked in the De Beers diamond mines. Their landlord was a man named William Simpson, who was a carpenter, working in the same mine. After Harry and Ethel were married, Maggie and William Simpson fell in love and were married.

Simpson was a Scotsman, but a nationalized American. He had a brother in North Dakota; he had lived there and had a claim of land but had not farmed it. William returned to North Dakota with Maggie and two babies, I think in 1911 or 1912. Louisa went there to help Maggie in 1913. My Mother had fitted Louisa out with a lot of lovely clothes. When she arrived in Ray, North Dakota, no one met her. She got a taxi and drove to the farm, about ten miles out of Ray. Maggie was living in a small shack, as their house was still being built. There was no bathroom, only an outside privy. They had been burning the grass around, and the children were black from playing in it. Louisa had a pretty dress on, hat and gloves. She felt so out of place and would have turned around and gone back, if that were possible. But being Louisa Lewis, she faced the music and soon changed into a house dress, and helped in every way she could.

Meanwhile, in 1910, Alfred got a good job as an engineer of a copper mine at Broken Hill, North Rhodesia [Zambia].

Caleb got home the 31st of December 1918, and we had to make plans to return to the College in Turkey. We returned to Smyrna in March 1919, with a large group of Near East Relief workers, travelling on the troop ship Leviathan, from New York to Brest, France. Then we travelled on a hospital train across France to Marseilles. A British hospital ship, the Gloucester Castle, took us to Constantinople. How differently the Turks received us! Now that the war was over, they were glad for our help.

The College had hardly any students the last year of the war. During the summer of 1918, the College became host to over two thousand disabled British military prisoners of war.

We were back in March 1919. That summer my sister Ruth came to visit us with her husband, John Longstaff, and baby Heather (Williamson now). Anna and King Berge came to teach at the College that year.

My sister Dorothy went to the Malay States in 1915, to be with my brother Jack. There she married Jim Latimer, the manager and chief engineer of a tin mine. Dorothy had twins--Peggy (Adams now) and Neil. She got cancer in her right lung, and in October 1920, Jack brought her to Smyrna with the twins who were then two years old. Jim’s leave was not due for six months, so he could not come with Dorothy. She was with us, at the clinic, until May 9th, 1921. Dear Mother took such good care of her. I took care of the twins, who were so very good. Jim was here with us when she died, a broken and sad man. She was buried near Neneka, in the lovely Boudja Church graveyard.

Note: The headstone is still in Buca cemetery, Dorothy Latimer (1888-1921).

Dorothy’s best friend was Sister Coats, a nurse who had been in charge of the B. S. Hospital at one time. She offered to be a Mother to the twins. My sister Ethel was free at that time to care for the twins on the journey. They were just three years old. So she went with Jim to England. Mrs. Coats took them to live with her in her lovely English home.

Jack was born February 6th, 1921, at our home in Paradise at 6 A.M.; Ethel was with me. Alfred went to Granny’s to give her the news. He said, “Mother had her 6th boy, at 6 o’clock, the 6th of the month.” Al was not yet 11.

My sister Dorothy’s death on the 9th of May 1921, was the first shock to the Lewis family. She had always been my favorite sister and to this day tears come to my eyes when I talk of her. She had nursed me in 1914, when I had T.B. I always prayed that if I ever had a daughter of my own she would be like her.

During the summer of 1920, the Y.M.C.A. in Smyrna ran a summer camp for Greek and Armenian orphan boys whose parents had been massacred. Arthur was asked to be a junior counsellor. He was a little over 15 years old, so it was quite an experience for him. When they got back from camp, Arthur wanted to build a cabin in the garden. He had watched how the natives made mud bricks and dried them in the sun, so he did the same. All the campus American boys came over to help make bricks. It was a nice little cabin, when he and Edward finished it. They even made a chimney and fireplace. But, Arthur was very anxious to go to America to preparatory school.

Mr. Rankin, who ran the Y in Smyrna, had a son Carl (Carl Rankin was later our ambassador to Formosa and is now retired, living in Maine), who had been to Mercersburg Academy, and he arranged for Arthur go to there. In July 1921, Arthur left on a freighter. He worked as a seaman for his passage since we could not afford to pay his way. So Arthur left home! He finally got to Mercersburg, having had many trying experiences. He was 16 years old (Arthur should write about his experiences on the ship and after he arrived in New York).

Well, to get back to 1922--it was a very important year for Turkey. Mustapha Kemal Pasha did away with the Sultan and he made many reforms. The one that did a lot to promote literacy was changing the Turkish alphabet to our own. He also did away with the fez and women could go about with their faces uncovered. The Greeks had been allowed to occupy Asia Minor in May 1919, after the great First World War, which they did. Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister at that time, was to blame for that, and for no end of death and suffering. Kemal Pasha formed an army and ordered the Greek army and all Greeks and Armenians out of Turkey. In September 1922, he marched into Smyrna, a great victor.

Those first two weeks of September before his arrival were a nightmare. As the Greek army retreated, they burned the towns left behind. The Greeks and Armenians tried to leave for Greece in boats from Smyrna harbor. They came to Smyrna on the trains by the thousands and the problem of relief for those poor people fell on the Americans, British and French in Smyrna.

The American destroyer, Litchfield, which was in Smyrna Harbour, sent twenty sailors with Sargeant Crocker in charge, to protect the College people. One sailor was stationed on top of the clock tower and the American flag was hoisted. From up there he could see when the “Chetters” (Turkish army irregulars) might try to get into the College campus, and a pre-arranged signal of three shots, would mean we must leave our homes and run into the main building for protection.

A few weeks before these troubles began, the College Y.M.C.A. had arranged a camp at Fokia. Edward and some other American, Greek and Armenian boys had gone there. They were playing baseball and they had large flat stones for bases. Edward ran into a base and his foot went under the stone and the next minute another boy ran and landed on the base. Eddie’s ankle was broken, so he was brought to Smyrna, and to the Clinic where Dr. Chassaud set it and put it in a cast.

When the sailor on the tower gave us the signal to get into the main building, Ed would pick up Jack (one and a half years old), and I took the baby, and we all ran. Our house was just outside the campus gate. One time shots were being fired all around us. Jack was old enough to get really frightened and a year later in Melrose, Massachusetts, he heard a car backfiring and he ran to me crying, “The Turks are coming!”

On Sunday, September 10th, an army of Greek soldiers were crossing the plain near Sevdik. The guns on top of Mount Pagus fired on them. The College was between the army and Mount Pagus. Some shell fragments fell on the campus, one only a few feet from where Edward was standing. Only God’s goodness preserved him. Caleb had to spend all his time doing relief work in Smyrna.

On Monday, the 11th, Dr. MacLachlan took Sargent Crocker and six of the sailors in the car over to the Settlement House at Prophet Elia (about three quarters of a mile away). The Chetters were looting the Settlement House. It was a foolish thing to do. Sargent Crocker was sent to protect the College. The Chetters would have killed Dr. Mac and the Sargent, if it had not been for a Turkish Cavalry officer, who heard shooting and came to investigate. (Divine intervention.) Dr. MacLachlan gives the whole story in his book of Memoirs, page 16.

On Wednesday, the 13th of September, Mrs. Caldwell, Mrs. Reed, Mrs. Birge and ourselves were ordered to leave for Greece with our families. Dr. Lorando and his wife and children also came. Miss Craig, the American girl who taught the American children and lived with me, also came. We went in a car, driven by a sailor and with an American flag covering the hood. The road was strewn with dead bodies, and Smyrna houses had all the shutters closed and doors locked. But looting was going on. We waited in the American theatre until we were taken aboard the destroyer Lichfield and landed at Piraeus the next morning. Arthur Godfrey, of radio and TV fame, was a member of the Lichfield’s crew.

Dr. Lorando had his wife and their two little children. The younger one died that night. I had a large room on the ground floor in a hotel in Athens and all the children slept in the same room with me. I got a spirit-lamp stove and prepared breakfast and supper for the children. We were there about a month before we got passage on a ship to New York.

Elections were going on in Greece and there was much tension. I had left a knife that I used to cut bread with, on the windowsill. Jack, still a baby, had a craze to throw things out of windows. Below our window there was a cafe with tables and chairs, where men sat discussing politics and drinking coffee. Jack threw the knife out of the window and it landed on a table, where some men were sitting. That started a riot as they thought it was done intentionally. Another time Henry got into an argument with some Greek boys and almost started a fight. Jack would yell at the top of his lungs, if I went anywhere without him. It was a very trying time.

When we got to New York, the dear Harlows met us all. The Birges and some of the teachers from the Girl’s School in Smyrna were on board and some Greek girls that Mrs. Birge helped on their passage. We were also met at the boat by our Arthur.

Louise Simon, a 15-year old Greek girl, was one of three sisters whom Anna Birge helped to come to America. All three were students at the American Girl’s School that was burning as we left Smyrna on the Litchfield, September 13th, 1922. Who started that fire no one really knows. Half of Smyrna burned. Mrs. Birge asked me to take Louise to live with me so she could help me and also go to high school. Mrs. Kennedy sent me a check almost every month. I was able to put money in the bank and with my brother Alfred’s help.

In August 1925, we returned to Izmir, as it is now named. We found many changes. No Greeks around any more. We were not even allowed to talk in Greek in public. We got a Creetan woman to work by the day as our servant. She spoke Greek. I felt terrible leaving my boys and going so far away.

The next summer, after Edward graduated from Brown, we managed to pay the passage of Edward and Alfred to visit us. A few weeks before they came, we had severe earthquakes and the house was badly cracked. We had to put our beds out on the veranda, as there were constant little quakes. In 1932, our house was all paid for. Ralph had gone to America in 1930. He lived at the Walker Missionary Home in Auburndale, Mass., and went to high school in Newton. He was always my most mischievous and naughty boy. He was the ringleader, while at Paradise, and got all the American boys into trouble. At the Missionary Home, it was the same old story. We felt it urgent that we should take the rest of the children and go to the States. Edward and Louise Calef were married on March 19th, 1932.

The College bought our house and Caleb came with us, to get us settled--he would go back and finish in another year. My daughter, Dorothy, had her 10th birthday. She was a lovely, loveable little girl. She, as well as Jack, had been having dancing lessons from a French girl in Boudja. She had so much natural grace--she made quite a sensation and people used to tell me she should take lessons and become a professional ballet dancer.

We left our home of twenty years on June 15th. Arthur was seven, when we moved there in 1912 and Edward was five, Alfred was two and a half. Henry was born there the month we moved in. Twenty years of joys, sorrows and pain. However, as I look back to those years, I can remember the joys, loving friendships, picnics and parties better than the sadness, pain and sudden partings. Pain is soon forgotten when there is joy and love in our hearts. Caleb was a wonderful husband and there was always love and understanding in our home.

We felt we had lived a good life in Turkey. Caleb’s students loved and respected him and they appreciated coming to his home.

Notes: Dorothy Smith is the last surviving of Helen Lawrence’s children and has kindly given permission of use of this article. In response to my questions the following details are noted. Mrs Smith spent the first 10 years of her life in Buca and the school she attended was at the home of a professor’s wife, a Helen MacFarland. She used to be a kindergarten teacher. There were four or five other students as well. Mrs Smith has stayed in touch with Kathleen Rowley, her cousin, who was the daughter of Rowly Pengelley. Kathleen has homes in England and either S. Africa or Zimbabwe.

Concerning the wealthy benefactor of the International college, Mrs Kennedy, all that Mrs Smith remembers is that she was from NY and was no relation to the Massachusetts Kennedys.

Mrs Smith has two books in her possession - one is Dr. MacLachlan memoirs “Sketches of Turkey”, and a history of the college written by Howard and/or Arthur Read. Click here to view a short segment of the former book and sample pages of the latter book. Helen Lawrence’s aunt, Grace Williamson’s eye witness account about the burning of Smyrna was recorded in a diary now viewable on-line. Copies of these were kindly provided (May 2005) by Helen Lawrence’s grand-son, Michael Smith of Orlando in Florida, who also kindly allowed the use of (June 2008) other photos of Turkey and the International College and its sister institution in Smyrna, the ‘Boys School’, viewable here: Click here for Mrs Dorothy Smith’s own memoirs. Dorothy Smith’s older brother Arthur, born in Turkey 1905, also penned his memoirs shortly before he died, viewable here:

Later on, May 2006, Alithea Lockie (nee Williamson), from Scotland, submitted sections of a 62 page diary kept again by Grace Williamson, but of an earlier period, 1914-18, but full of insights covering everything from the price of day to day items to the perception these ladies had of the political situation, their safety, and a commentary on their community and it’s characters, viewable here. Mrs Lockie also submitted some photos handed down from her grandfather John ‘Jack’ Williamson, eldest son of William and Elizabeth. From the contents of the diary, it is clear the maternity home was across the Punta railway station, however tying the building to today’s relicts is problematic.

Mrs Lockie also provided some information concerning her grandfather: ‘I do know a fair amount about my grandfather although he died before I was born. He was the eldest son of William and Elizabeth and also known as Jack. He was very much loved and respected by all who knew him wherever he lived and was regarded very much as the head of the family. It appears that he supported many of his relatives and found employment in his numerous enterprises for a good many of them. This did not prevent him from making three fortunes and loosing three fortunes. Among these were the contract for dredging the Suez Canal, a dye making process using the Sumac tree, etc. His obituary (written by his brother-in-law) gives a bit more detail, which at the time of publication seems to have raised a deal of correspondence in the paper as to the exact details of Kitchener’s request for leave and the permissions granted to him! Hover here to view.

I know less of the earlier generation, my great-grandfather William Williamson, but there are clues on the back of a portrait of him as a young child, which on its reverse is inscribed that he was born in Cleckheaton, Yorkshire and died in Malta in 1882. Our family records give his parents address as The Grove, Cleckheaton and I have made a preliminary attempt to locate it on a map. Finding Cleckheaton is easy enough but honing in on ‘The Grove’ (the name that my grandfather then gave to the magnificent house he built in Egypt) is not so easy. Why he died in Malta I don’t yet know but his tomb is in Buca cemetery, clearly him as dates match. Would they really have brought his body back from Malta? Could it be a symbolic tombstone? I don’t know.

I had heard that we got our curly hair from our Italian blood and as my great-grandmother Elizabeth was the daughter of Henry Richard Barker and Marie Therese, maybe Marie Therese was Italian! From this posting, I have learnt that Elizabeth Williamson (nee Barker) had the nickname ‘Neneka’, though I have never heard her called that.

Note: According to fellow contributor Edward de Jongh, Neneka is derived from Nene, the Greek for grandmother or sister of grandmother, with the ending adding affection to this ‘Smyrniot’ designation.

The Williamson family spent much time in their retreat at Asprokremnos (Aspro) on Troodos mountain, central Cyprus, that was on lease hold from the Cyprus government and that expired long ago. I am told that the site is earmarked for a summer palace for the archbishop of Cyprus but as far as I know, apart from some demolition, the work has not yet started.

I have wonderful recollections of the place and there are photos of me in my childhood sitting in the same spot as photos of my father sitting there at the same age a mere 43 years earlier.

In the early years of my life all the various branches of the family would go there during the summer as it was so much cooler up in the mountains. It was a sloping site with a terraced orchard which looked like a pink and white confection in the spring, there were three houses spaced out around the place. The original stone house which my grandmother and all her immediate family would occupy. The ‘hut’ which Aunt Effie (W. Henry Williamson’s widow) and her family stayed in made up principally of WWI era prefabricated wooden buildings (probably shipped over from Egypt) but never-the-less very comfortable and Great Aunt Alithea’s house, a bungalow with lovely views which accommodated her, any over spill of family members and visitors.

However, the Cyprus emergency 1955 - 1960 changed all that and we were unable to use it as much. My parents and I left the island in 1960 and I am told that immediately after the Turkish invasion Aspro was used by refugees.’

Most of the main trunk of my family tree is contained in the family bible which my father gave to Robin for safekeeping as he was the eldest male Williamson of the next generation. I have photocopies and it goes back to a Richard son of John Williamson who died at Cleckheaton in Yorkshire in 1703. How the family got out to Smyrna I do not know.

To visualize a simplified family tree, click here:

As a child I was told that there is a book called “In the Steps of Saint Paul” in which the author (I don’t know who the author is) mentions a meeting with Alithea. I've always meant to find out more.

Note: The administrator of this site investigated this possible book in Sept. 2006, and the book gives a good impression of the house in which Grace Williamsons continued operating in the early 30s, but now as a pension, details: There appears to be no reference to Alithea in this book.

Both Alithea and Grace must have been ahead of their time in so far as womens’ lib goes! They were definitely women of character as indeed are all Williamson women. I don’t know much about Grace. She died before I was born but I do remember (just) Alithea. She was everybody’s favourite aunt.

Note: There is an obituary of Alithea Williamson printed in the Izmir Anglican Church publication ‘Candlesticks’ viewable here and also an obituary of a nephew of her’s, Douglas Richard Williamson viewable here:

Although we don’t yet know which house the Williamsons had in Boudja, it would appear that the nursing home that Grace and Alithea opened in Smyrna was somewhere on the square near the station.

Note: From Donald Simpson’s account of the Smyrna Anglican Church life history, we see the death of Grace Williamson was a real shock to the community - details - however there is a 3 year mismatch on year of death between this and family records. But the Bornova cemetery records, where she is clearly buried, confirms this date of 1945.

A cousin of mine told that there is a book entitled “Maadi 1904 - 1962” by Samir W. Raafat makes several references to our mutual grandfather, John Williamson. I’ve wanted to find out more, but the book is prohibitively expensive.

Note: The administrator of this site investigated this book in Feb. 2007, and the book gives a good impression of the house and activities in Egypt of Mr Williamson, and Mrs Lockie provided the photos to complete the picture, viewable here:

There are many references to the Westerners living in this area of Cairo, making it an excellent reference.

The family trees in the possession of Mrs Smith show that quite a few of the Williamson, Lewises and Pengelleys married within the English community there in Boudjah.

WILLIAM WILLIAMSON (1827 - 1882) m. Elizabeth Barker in Smyrna and had the following children:

1) Leila (my grandmother) m. William Lewis in Smyrna and had:

a) William

b) Margaret*

c) Richard m. Mabel W.

d) Helen (mother) m. Caleb Lawrence, (7 children, one Dorothy)

e) Mary

f) Ethel m. Henry Pengelley

g) Louisa

h) John

i) Dorothy

j) Ruth

2) Mary m. W. Wilkin and had:

a) Mabel m. Richard ‘Purdon’ Lewis (3 children)

3) John m. (illegible) (5 children)

4) Nellie m Alfred Pengelley and had:

a) Doris m. E. Charnaud

b) 5 other children

5) Louisa m. A. Hichens

6) Rebecca m. Rowly Pengelley and had:

a) Jessie m. Stephen ? and had:

i) Kathleen (my mother’s cousin) and 2 other children

b) 4 other children

7) Bella m. E. Thorman and had:

a) Laura m. ? had 3 children

b) Margaret m. R. Henderson and had

i) Ronald and 3 other children

8) William m. E. Charnaud and had:

a) Martin

b) Joyce

c) Douglas

d) Andrew

9) Ester m. Perkins

10) Grace

11) Charles

12) Alithea m. F. Whittall

REV WILLIAM BUCKNER LEWIS m. Margaret Purdon and had

1) Arabella m. Walter Murray Pengelley in 1854 and had:

a) Alfred m. Nellie Williamson (see above)

b) Rowly m. Becky Williamson (see above)

c) Henry m. Ethal Lewis (see above)

d) 15 other children

2) William (my grandfather) m. Lelia Willamson (see above)

3) 4 other children

Notes: 1- Using the above listing as a reference, we see that many of the names crop up in the Buca cemetery - listing. Following the order, William Williamson (1827-1881) is present in the graveyard, together with his wife Elizabeth (1832-1919). Of their 10 children listed above, at least 4 died as adolescents, of which 2 can be matched up to the list (Margaret 1872-1874, Sarah Ruth 1869-1874) and 2 cannot (Frederick Edward 1868-1872, Richard James 1861-1868). Thus they might have had more than 10 children. Similarly the offspring who lived till adulthood cannot be matched (C.B. 1871-1925).

2- Diary of Maggie Simpson (nee Margaret Lewis*) of her time at the Lebanon Hospital for the Insane, in Beirut. The diary starts in July, 1906 with her trip on horseback up Mt. Hermon through Christmas, 1907 when she moved to Kimberly, South Africa to live with her brother and sisters. Maggie and her husband eventually moved to Ray, ND. The diary includes a rather interesting description of a nurse in the care of the mentally ill.

3- William Wilkin (1824-1978) was the director of the Ottoman bank whose wife is named as Marianne Louise Rosalie (1838-1874), who probably is Mary, both again buried in Buca.

4- In Bornova the couple Nellie and Alfred Pengelley are represented as Ellen (1868-1934) and Alfred W. (1856-1928), and their child, Doris E. Charnaud (1894-1956) is in the same cemetery, as well as her probable husband Edwin J.C. Charnaud (1886-1961). Rebecca M. (1859-1936) and ‘Rowly’ Rowland A. Pengelley (1861-1933) are also buried in that cemetery.