Ten years ago, I knew very little about my ancestors. But with the help of four documents left by my father, of my late cousin Serge de Hübsch, of other descendants1 of the d’Andria and of Internet, I have been able to rebuild a large part of our genealogy. The following article describes my findings.

D’Andria was a common surname among the Latin families in Chios. I use the particle “de” with Andria, by which I mean to show that at one time my ancestors decided to modify the name in order to differentiate themselves from their relations.

Settlement in ChiosSupposedly reliable documents of the Chios diocese affirm that Giuseppe d’Andria and his father, Dr. Marius d’Andria, were descended from a Pantaleone who had come from Genoa and settled in Chios. The date given of his arrival, 1565, raises questions. A previous note from the same diocese linked the branch known as the “Stevanachi/Marachi“ to a son of one Niccolo, named Pantaleone, who died before 1569, according to a deed by the notary Stefano de Portu. However, the note was neither dated nor signed, but it was surely written between 1787 and 1808, because in it, Marius’s sister Apollonia is referred to as living and as a widow, and we know that her husband Nicolao Giustiniani was assassinated by bandits aboard a ship in July, 1787 and that she died in 1808. |

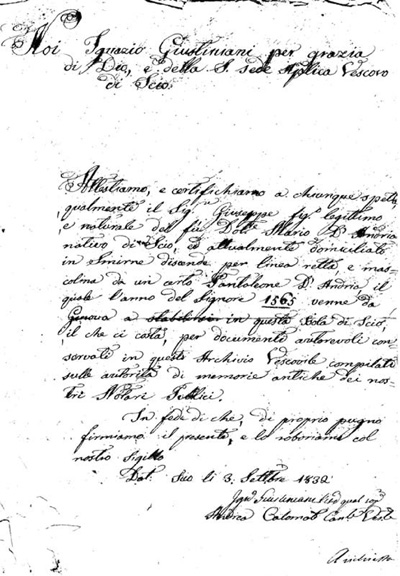

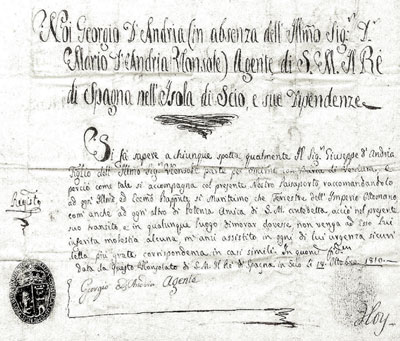

Episcopal affidavit on the family’s origin, dated Sept. 3 1832 |

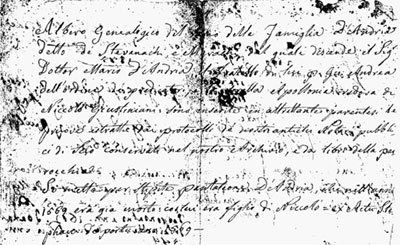

|

Episcopal note, undated and unsigned, on the origin of the branch. |

The most likely date of the document seems to be 1789, as it is oddly similar to the one drawn up in that year at the request of another Andria branch, that of Paul Ellis, Marie-Anne Marandet and Elisa Petitta, a branch which, until recently, had no confirmed ties to Marius. That document unequivocally established their branch as descended from a Genoese Pantaleone, whose son Antonio, also Genoese, had the notary Stefano de Portu record, in 1569, a testimonial dividing his property between his two brothers, Episcopal affidavit on the family’s origin, dated Sept. 3 1832 Episcopal note, undated and unsigned, on the origin of the branch. Paolo and Gasparo, and stating that Pantaleone was deceased. |

Today, an in-depth analysis of the surviving Chios baptismal registries provides evidence for the existence of a Pantaleone, but the date of his arrival remains in question: When in 1566 Turkey took over the island, the inhabitants became ipso facto subjects of the Ottoman Empire. However, newly arrived immigrants were in fact permitted to retain their nationality. Two and a half centuries later, during the upheavals of the 1820s, in order to obtain a passport it was necessary to prove without a doubt one’s national origin. Many Levantines wanted to show that those later arrivals were their ancestors so they could prove citizenship of another country. Many members of families who had lived for a long time in the region could not do so. They were therefore considered Ottoman subjects, a much more fragile and less favorable status than that of foreigners who benefitted from protection by their consulates. Later, when the Empire collapsed, those who had not established their origins in time found themselves stateless.

Another reason to question the 1565 date is, as we’ll see later on, the substantial number of progeny from 1580 on.

We know little about the six or seven generations after Pantaleone. Between him and Dr. Mario, born in 1743, the bishopric of Tinos, which currently holds the Chios archives, proposed four links as recently as in 1955. Working backwards: Ignacio Lorenzo Stefano (b. 1711), Andrea (dates unknown), Stefano (b. 1629), Mario (b. 1601) and Niccolo. We do not know much about Andrea and Nicolao / Niccolo because the relevant parochial certificates disappeared. The Episcopal letter shows Nicolao / Niccolo to be the beginning of the line, although he does not appear in his putative brother Antonio’s will.

Although the first surviving records of Chios go back only to 1583, and are seriously deficient on entire time periods, the records contain many certificates that refer to Andrias, and at quite an early time.

The name Antonio appears showing at least 6 children, while his brothers Paolo and Gasparo had three each. According to custom, each of them named his eldest son after their grandfather: Pantaleone. However, when we look at the godfathers, we still find several other Pantaleones whose fathers seem to be contemporary with Antonio and who might be his brothers. Marino (deceased prior to 1583), Mario (deceased prior to 1605) and Pasquale. The only known Marino’s son was of course named Pantaleone. Mario had at least two sons, named Pantaleone and Nicolao. He appears then as the missing link between Nicolao and Pantaleone. Pasquale seems to have had seven children.

Contrary to what Antonio’s will, leaving out his brothers, suggested, namely that there were distinct clans, the baptismal records of Pantaleone’s grandsons show that, in fact, most of the family members were godparents of each other’s children, without exclusion.

For the sake of completeness, it should be noted that other Andrias could be found in records as early as 1585, some of whom are godparents. This means that these latter (Pietro, Giovanni) are contemporaries of Pantaleone’s children, or in other cases, of their father himself (Francesco, Benedetto’s father).

It is unlikely that these adult Andrias are all descended from just this one Pantaleone, because that would suggest that he was not only remarkable fertile but also divinely favored, given the high infant mortality of the time (on average greater than 50%).

At this stage, we can only formulate hypotheses: 1) other Andrias may have arrived before or with ‘our’ above-mentioned Pantaleone, 2) a second Pantaleone’s marriage could explain the different treatment of Mario and his brothers in the will. 3) In addition, Marino could be a wrong spelling of Mario, splitting the single individual into two. I believe that at least the two first assumptions are valid.

It is interesting to note two phenomena that demonstrate the extremely rapid and successful integration of the ‘newcomers’ into the local population.

1. The name Andria occurs very frequently in one way or another in the first baptismal registry between 1583 and 1652. That name is the third most common after Giustiniani and Castelli.

2. Links with the Andrias - marriages, godparents - involve a number of the main Catholic families residing on the island at the time, and particularly frequently with the Giustinianis, the d’Andorias (easily confused), Argirofos, Bavestrellis, Mascardinis, Montanaros, Morettos, Stellas, de Vias, Vuriclas, etc.

According to birth registries, in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, about a hundred people named Andria lived in Chios among some four or five thousand Catholics. Presumably, like all their co-religionists, they had been driven out of the Kastro after the Florentine raid in 1599, and lived partially off their property and partly from trading. Some chose to join religious orders. A few became doctors and / or consuls (of different states), professions that allowed them to also be businessmen or property owners. These were occupations that the Ottomans willingly abandoned to the “unbelievers”, reserving positions in the army and administration to the Muslims, who were quite few on the island.

As an illustration of the atmosphere at the time, Stanislas d’Andria and Antonio Grimaldi, both friars, together with four heads of the main Catholic families in Chios, were “shackled and thrown on a galley which took them to Rhodes”. After the Venetian left Chios in 1595, the Greeks accused the teaching friars of reopening two very successful classes, in spite of their being banned. The friars were released only after Louis XIV’s ambassador to the Sublime Porte intervened, in 1706.

To return to our line, we find now the following sequence:

Niccolo (born ca. 1480)

Pantaleone (ca. 1515-1568)

Mario I (ca. 1540 – ca. 1595)

Nicolao (ca. 1575 -?) married Geronima, called "Mimina" Stella in 1607, and had many children with her. However, his first two - Mario II and Geronima/ ‘Mimina’ – were born before that wedding date. They may have been his issue by Stephanie de Portu.

At this point, my reconstruction differs from that of the bishopric because of Mario I (and the question of the family’s arrival in Chios in the year 1565).

Mario II (1601 -?) married Nicoleta Domestico in 1623. They had many children, Stefano being the fourth, in 1629, and Angela, the fifth, in 1630 who married Natale (1651) and Pietro (1667) Castelli, successively.

Stefano I (1629-before 1702) married Maria Giustiniani in 1655. The baptisms of his children are in a problematic period for the registries. However, we know that his daughter Monica, called ‘Manani’, married Nicola Timoni in 1702. His other known children were: Angela, Nicoletta, and Andrea. This last, born circa 1670, married Appolonia Draco in 1698. Three years before the wedding, the Turks had hanged Francesco, Appolonia’s father along with Pietro Giustiniani, Domenico Stella and Giovanni Castelli as retaliation, believing that they had encouraged the Venetians to occupy Chios (1694-1695). Andrea’s wedding act did not name his father who is, however, named in the one between his daughter Anna Maria and Goffredo Timoni. Referring to a celebration in the house of ‘Andrea son of the late Stefano’ the certificate confirms his place in the lineage.

It should be noted that in 1720-21, two Andreas d’Andria – one of whom is surely Stefano’s father – were among the borghesi who clashed with the Giustinianis about paying the costs of rebuilding the St. Nicolas cathedral destroyed after the Venetian occupation. A Giuseppe d’Andria appears on a 1727 list of notables who refused to pay those costs, and he appears again on a 1735 list of those requesting that Mgr Bavestrelli be relieved of his duties. These items share a common thread: they point to the influence of the Andrias in the Catholic community in Chios. These were men ready to stand up against narrow-minded conservatism and the rigid perpetuation of the past.

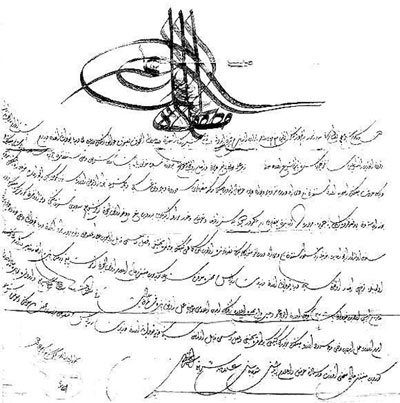

Text of the Bougourtou “An order from Mustafa III on 8 muharrem 1177 (6/5/1763) to the kapudan pacha (great admiral) and to the Chios nahib: Following the request made by the miscreant Istafan (Stefano) and four other miscreants regarding the property they have worked in Chios since 1150 (1748), which is contested by the administrators of Piyale pacha’s evkaf (deeds), order to examine the matter in accordance with canonical law.” |

The most likely date of the document seems to be 1789, as it is oddly similar to the one drawn up in that year at the request of another Andria branch, that of Paul Ellis, Marie-Anne Marandet and Elisa Petitta, a branch which, until recently, had no confirmed ties to Marius. That document unequivocally established their branch as descended from a Genoese Pantaleone, whose son Antonio, also Genoese, had the notary Stefano de Portu record, in 1569, a testimonial dividing his property between his two brothers, Episcopal affidavit on the family’s origin, dated Sept. 3 1832 Episcopal note, undated and unsigned, on the origin of the branch. Paolo and Gasparo, and stating that Pantaleone was deceased. Stefano II, named after a deceased brother, was born in 1711, thirteen years after his parents were married. He died around 1778, according to his grandchildren’s baptismal records. Except for the bougourtou shown here, we have little information about Stefano. Because of missing records, we know neither the date of his marriage with Minetta Corpi2 nor that of the baptisms of his children. The first known child is Giovanni (b. 1736), who will be followed by four girls and four boys, the last of which, Andrea (b.1749), may have taken the name of a deceased brother. |

|

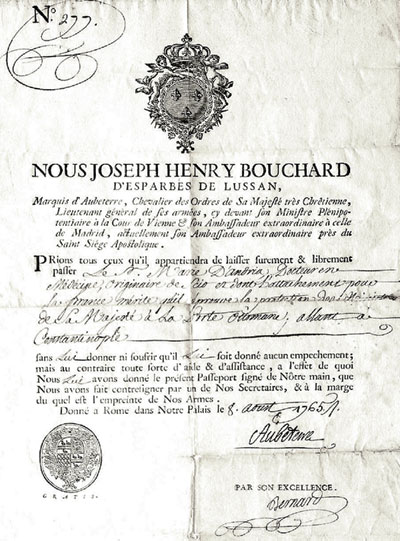

Apparently Mario III, born second to the last, in 1743, was the only Stefano’s son who had children. In 1758, he was enrolled in the Greek College of Rome on an Allatius scholarship3. In 1762, he earned a degree in Art and continued to study medicine in Rome. In August 1765, he left with a pass delivered to him by Joseph Boussard, the French ambassador. In 1770, he married Maddalena Marcopoli4, age 14, the daughter of a Chios physician. The wedding attendants were Dominico Marcopoli and another physician, Nicola Timoni (a relation to Emmanuel Timoni, who, it may be noted, long before Jenner, practiced inoculation (variolisation), the first historical form of vaccination). Nicola’s wife bore many children between 1774 and 1796: thirteen are mentioned on the island’s christening register. They included four boys. The first boy was born in 1779, after four girls, and was baptized Stefano after his grandfather. Another boy named Giuseppe was the eighth child, born in 1785. ‘Our’ Giuseppe was born in 1794, followed in 1796 by Andrula, the youngest male child. The second Giuseppe is the only one for whom I was able to find descendants, which makes me think that his brothers died prematurely. |

Mario’s passport as a newly graduated doctor of medicine, upon leaving Rome. |

|

Giuseppe d’Andria’s passport. He will take the name Joseph Marius de Andria. Curiously, his father Mario, the Spanish Consul, was not there to sign the document. He may have been in Constantinople. |

As young as sixteen, he obtained in 1810 from his father the Spanish consul –Joseph Bonaparte was then king of Spain– a safe-conduct for the ‘barca di Ventura5’ to Smyrna. The second youngest of the brood, he decided so to strike out on his own on the continent, 3 years before his father’s death and 12 years before everyone else was to do the same under duress. Giuseppe's sisters – at least those who reached adulthood – married in Chios, scions of prominent families. Two of the sisters’ marriages require no comment: The third, Angela, and the fifth, Battistina, married around the age of twenty, Domenico Castelli and Giovanni d’Andria, respectively, the latter, a distant cousin who shared the common ancestor, the first Pantaleone. In other households, the age gap between spouses was less common: Andrea Macripodari was more than 20 years older than Maria, the eldest; the widower Ignazio Marcopoli, was 17 years older than Mineta. Calomati Pietro was 18 months younger than Caterina, who married at 28, and Angelica was 8 years younger than her husband, an attaché de consulat. |

The small number of children marks another difference from the previous generation: only Giuseppe had as many as twelve. As for the others, assuming we found all the baptismal certificates, their issue ranges from a single child each, for Mineta and Caterina, to seven for Battistina.

Apart from Giuseppe’s descendants whom I will examine below, the only others I have been able to identify on the continent are the Battistina and Angelica’s descendants. Mario occupied a prominent place on the island. He seems to have been important in influential consular, medical and commercial circles, and was repeatedly invited to be a godfather or a witness. In all likelihood, he spent time in Constantinople several times. Between September 1805 and July 1806, and then again in 1811, he was there as a witness at the weddings of three couples of Chians. He last appears in 1812 in Chios, at the baptism of his grandson Pietro Calomati. His death in 1813 marked the loss of the last of the great figures of the Chios branch of the family.

Nevertheless, Andrias (of another branch) lived in Chios where, as recently as in 2009, the owner of a distillery reported that he bought the premises from a Michele, and where some maps of the Campos show houses listed as belonging to “d’Andria”.

A Century on the Continent.The move to the continent, even partial, of a clan as large and diversified as the Andrias took place, of course, over time. The inscriptions on a tombstone at the Feriköy Latin cemetery in Istanbul, unfortunately damaged in 1864 when the cemetery was moved, mentions a Joannes (Giovanni) d’Andrea, native of Chios, who died in 1677 in Pera. According to the Latin epitaph, which is difficult to decipher because of truncated lines6 and the frequent use of abbreviations, he lived to age 82 – therefore, he would have been born in 1595– was held captive in Tunisia (a major pirates’ refuge), ransomed, had many children, and was paralyzed for the last 40 years of his life. Unfortunately it is difficult to identify his descendants with certainty. One Giovanni d’Andria (who may the one cited on the tombstone) is mentioned in 1626, as a procurator at St. Jean. A record shows Lorenzo and Domenico d’Andria as sub-priors at the Magnifica Comunita de Pera, the former in 1656 and 1680, the latter in 1662. Later, other Andrias became well known in Constantinople. A passageway in Galata was named after them. At the beginning of the 20th century, an Andria owned The Hotel de Londres, built on the site of an old Glavany house. Graves in Istanbul’s Catholic cemetery contain several generations of Andrias from Chios. The oldest are of those persons born at the beginning of the 19th century while the most recent death occurred in 1997. This last is probably of the branch that, in the early 1900s, was responsible for fitting out a 1,200-metric ton ship, a relatively large one at that time. By 1864, that branch had joined the St. Anne’s Confraternity. As we shall see, at the beginning of the 20th century, those who were part of my grandfather’s family and that of at least one of his brothers joined the Constantinople d’Andrias. Today, my second cousin Remo, who lived in Smyrna for quite some time, continues to represent the de Andria family in Istanbul. In the middle of the 19th century, Andrias resided in several other cities of the Ottoman Empire, mainly Salonika and Gallipoli. One descendent of the Chios group lives in the Dardanelles area, a ‘Michel’ (actually François Jean Auguste, nicknamed Michel in memory of a deceased brother) who was then Vice- Consul. During the Crimean war, he was helpful to the Allied forces, and became a successful and highly decorated diplomat, receiving the Legion of Honor, allegedly from Napoleon III, himself. Following his example, many of his descendants became diplomats, notably as French Consuls in various Eastern Mediterranean cities. |

Giovanni’s tombstone – Translation Read this, Passer-By! Here lies Jean d’Andrea, who was born in Chios to a noble family and suffered captivity in Africa. Released for ransom, he settled in Pera and fathered blessed offspring. He lived to see his children and his children’s children. An illustrious man, both because of his honest morals and his penetrating mind. Rich in merits to the age of forty, he spent another forty-two painful years stricken with cruel paralysis, which he endured with remarkable patience. While in this state of suffering, he gave up the spirit to his fatherland, surrounded by his caring children and the tears of his loved ones – 1677. With a little bit of imagination, one can make out the – crownless – eagle on the tombstone, which tops the coat of arms used by many branches of the family. |

Smyrna

Let us return to Giuseppe, whom we left as he was departing from Chios. He established a home in Smyrna and started a family early by marrying a very young woman of “Persian” origin, Catherine Micridis (1802-1871). Between 1817 and 1842, she bore him six boys and six girls. In December 1822, when Giuseppe was just 28, he signed his name along with about fifteen other “Catholics from the Chios diocese residing in Smyrna” –Aliottis, Giustinianis, Reggios, Castellis, Badettis– to a letter announcing the offer of 3,000 Roman crowns to assist poor Catholic families on the island, and to repair the St. Nicolas cathedral, which had been badly damaged by the Turks in a terrible repression. In this way, Giuseppe joined the ranks of the Smyrna notables. They included Michele d’Andria’s sons, his namesakes who had previously been Austrian protégés, and the only d’Andrias to appear in the 1826 census, the first conducted by the new Sardinian consulate.

In September 1832, Giuseppe obtained from the Chios diocese the affidavit that established Pantaleone as his ancestor. Unlike most affidavits, this one lists him as the only recipient, which seems to confirm that his numerous siblings had not joined him in Smyrna. The document allowed him both to prove his Genoese origin and to become a Sardinian citizen. This was unlike many Genoese families who opted for keeping French nationality, automatically granted when the Napoleonic Empire briefly annexed Genoa (1805-1814). |

Giuseppe’s signature |

Consequently Giuseppe is listed with his wife and children in the second Sardinian census of 1842, as a sensal [broker]. After that, his signature appears alongside those of one or another son on the many petitions, subscriptions and attestations drawn up by Sardinian, Italian or Levantine notables. He is specifically listed on the registers of the Brotherhood of Our Lady of Mount Carmel (together with Giovanni Battista, his second son, nicknamed Gigibi or J.J.B.). In 1853, along with his eldest and third sons, Marius and Stefano Alessandro (‘Et. Al.’ on the document), he signed an attestation supporting Isaac Missir. In 1855, he helped found ‘l’Associazione sarda per soccorso a nazionali indigenti’ (again with Gio. Batt.); and in 1856, the whole family contributed to a fund to purchase 100 cannons for the motherland, at the request of the Sardinian Consul.

The first names Giuseppe, Jean-Baptiste, Etienne Alexandre, and finally, Pietro are also found on a subscription for the impoverished families of mobilized troops in the War of Italian Independence (1860). |

Etienne Alexandre’s signature |

|

The then-recently formed kingdom of Italia rewarded the family’s loyalty by bestowing the title of cavaliere to Giovanni Battista (1819-1900)7. Between 1842 and 1847 the family took formal steps to replace the ‘d’ with ‘de’, in order to avoid the frequent loss of the apostrophe. In a letter from 1927, Marius de Andria reminded his cousin, our grandfather John, that Giuseppe –their common grandfather– exhibited in his dining room “two charts showing our kinship to the Grimaldis”. This is the type of document that likely encouraged the family to make more or less well-founded claims to nobility, at a time when Smyrna’s leading Italian families - Aliotti, Castelli, Solari– all competed for that status.

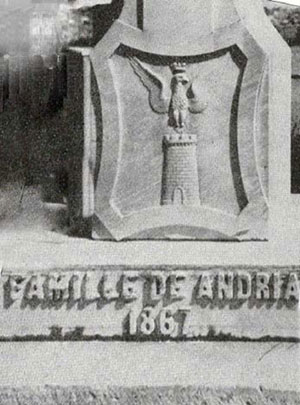

The coat of arms above our ancestors’ family tomb (after Livio Missir). The Kemer cemetery in Smyrna no longer exists. |

I do not know whether these charts still exist, or where they might be found, but we do know the coat of arms the family was bearing. While the other branches, following the example of other Smyrna families, took up the Chios Giustinianis’ arms, themselves derived from the Zaccarias’, the ‘de’ Andrias transformed the three-tower castle into a single tower and added a (count’s?) crown. Note that this single tower is already visible on the right side of the seal of the Giuseppe’s passport. “Gigibi” became “a very large property owner in Smyrna, and held shares in many commercial firms and companies in the city”8. He was one of three “foreigners” who, in 1868, had a seat on the short-lived Smyrna town council. The negotiations between the Ottoman authorities and the European consuls on upgrading the land tax on European properties in Smyrna led, in 1874, to the development of a joint committee of European and Ottoman property owners, whose Italian representatives included Pierre and Ange Aliotti and Jean Baptiste d’Andria. They were chosen because of the size of their properties and their prominence in the Italian “colony”. Gigibi married Anne Esther de Portu9, 17 years his junior. They had four children. One son, Ilario Luigi, would run one of Smyrna’s main Italian commercial firms at the beginning of the 20th century. The other, Alcide Théodore (1864-1946), emigrated early to the United States. He performed as a baritone, published French songs (especially Christmas carols) and, in 1919, taught French at Boston University. |

|

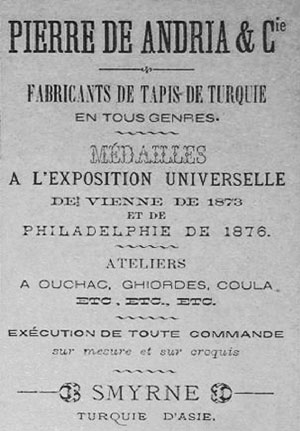

Advertisement of P. de Andria & Co. in the Annuaire de Smyrne. |

By the 1850s, Gigibi’s brother, Stefano Alessandro de Andria, was listed in the archives as an important Sardinian banker. In 1856, he held the Directorship of the E. A. de Andria and Sons Bank. He “Frenchified” his name to Etienne Alexandre, and used ‘de’, as noted above in his signature of 1853, which held a mortgage on a distillery belonging to a French merchant, B. Carle10. By the turn of the century, he would own a steam mill (for which he would be listed as “associate owner”) in Karatach, in the Southern part of Smyrna. Undoubtedly trustworthy, he was named executor by his first cousin Stefano d’Andria, Battestina’s son, Gilbert’s father and Bernard d’Andria’s grandfather (see Stefano’s will and testament) and by his brother-in-law Antoine Giraud (see below). Another of Gigibi’s brothers, Pietro or ‘Petrakaki’ –little Peter in Greek– lent his name to the ‘P. de Andria & Company’, even though he was only nine years old when it was apparently founded in 1836. According to A. Frangini, his partner was Antoine Giraud, who was only five years older (and would become his brother-in-law when he married Peter’s sister Elisabetta). The 1891 Ottoman Business Index shows that Petrakaki’s older brothers, Mario (born 1817) and Etienne Alexandre (Stefano Alessandro, born 1821) had been involved in founding the firm, but abandoned it in 1868. From 1881 on, Petrakaki had his sons join the company, causing A. Giraud’s departure11. |

|

The company may have started on shaky ground, but it specialised in manufacturing and selling oriental rugs, for which by the middle of the 19th century, the market was quickly developing. This article of decor, which until then had been considered a high-end luxury item, became all the rage among the increasingly wealthy Western bourgeoisie in Great Britain, the Netherlands and, later on, America. To meet the soaring demand, Turkish production increased. Most of it came from Anatolia and especially Uşak in the Smyrna countryside. Using semi-industrial techniques, yet maintaining traditional quality, the firm (whose warehouse was next to the Greek church of St. Photini) outdid its competition. The World’s Fairs began to display rugs and present awards. ‘P. de Andria & Co’, registered with the Marseilles Chamber of Commerce and Industry, received several awards in 1873 (Vienna), 1876 (Philadelphia12), 1893 (Gold Medal, Chicago) and 1906 (Milan). It prided itself on being the oldest carpet company in Smyrna and had branches in Constantinople, Paris, London and Tehran. |

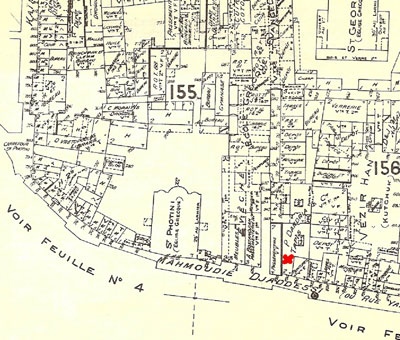

Location of the P. de Andria & Co warehouse on the map of insurance firms (ca. 1904). |

|

It was the official supplier to Paris’s Bon Marché department store, and assured its clients that it was able to fulfil all orders, including custom-made rugs; and, finally, it was the “only firm with its own dyeing factory (‘In-House dyeing in Ouchac’), which would ensure stable colours.” This last boast was aimed at the competition, which was industrialising the manufacturing process, mainly by using chemical rather than natural dye. By 1900, six companies controlled 80% of the Turkish rug exports in Izmir, Petrakaki’s being the second largest. Upon falling ill, as early as in 1882, he passed the management, first, to Nelson, who had studied in Lyons, eventually to all the other sons. This injection of fresh blood into the firm brought about vigorous development, especially internationally. Thanks to his success, Petrakaki was considered a veritable patriarch: he appears on the parish registers, often with his second wife Caroline, née Romano, as best man for most of his children, then as godfather to his grandchildren. He was said to have designed some of the carpet patterns himself. He also ensured that his less well-off or attractive nieces married well. Thus, he created a clan of sorts around him, which set itself apart from the other Andrias by its noble particle. |

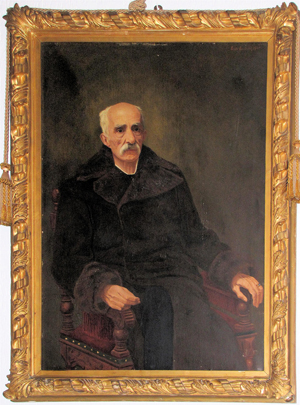

Pietro de Andria, aka Petrakaki by Ovide Curtovich. |

|

Advertisement of P. de Andria & Co. in the Annuaire de Smyrne. |

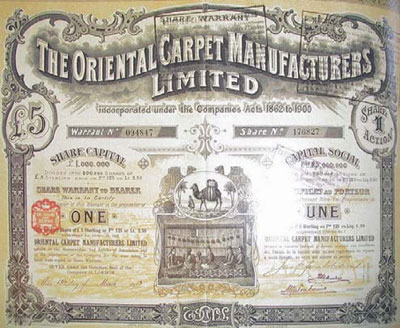

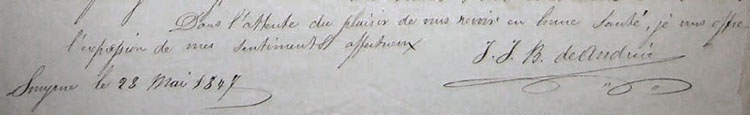

One can reasonably assume that the Andrias spoke French. The proof lies in the spelling of their first names, the firm’s advertisements, the commercial letter in perfect French by J.J.B. (Gigibi) in 1847, and the engravings on their tomb at the Kemer cemetery as recorded by Livio Missir. Yet they were still Italian and practiced some form of endogamy, marrying only into other Levantine families of varying origins but of the same social standing. Most were Chians of Italian descent, with the family names Aliotti, Castelli, Dracopoli, de Portu, Giudici, Giustiniani. “Persian” families – Balladur, Caraman, Issaverdens, Micridis, Missir– were also well represented, as were the French – Bon, Caporal, Guys, Michel, Roboly. Finally, British and Dutch families were also represented: Edwards, van der Zee. As for Pietro, he was fond of giving his children English names: Nelson, Herman, and John instead of Giovanni. Immediately after Petrakaki’s death in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, in 1907, his company merged with several competitors in Smyrna and became “Oriental Carpets Manufacturers Ltd.” The carpet manufacturing and trading corporation, first chaired by Nelson, the eldest, then by the third son, Herman13, was listed on the Constantinople and London stock exchanges; then at the formal request of Raymond Poincaré, on Paris’s exchange. The company had offices in those capitals. Purchasing inventory in Turkey and Persia, the firm occupied a dominant position in the profitable rug market: it was reputed to control 75% of production, and, by 1911, it employed 46,000 people, the vast majority of whom were women and girls in workshops of various sizes in country towns. After an impressive beginning -the stock price had increased fivefold just before the Great War- the corporation was faced with a number of setbacks. Having barely recovered from the wartime interruptions, it saw its middle class clients diminished by the Great Depression. |

Then too, decision-making was split among London, Paris and Smyrna –not to mention the relatively autonomous American branch, so the managers often delayed taking necessary measures, and as a result, were forced into a lengthy process of successive restructurings. Nevertheless, the business managed to stay afloat until the 1980s.

OCM and its predecessor had allowed the entire extended de Andria family as well as other eminent Smyrna families to live comfortably for years, at least until World War I. Herman continued as President of OCM into the 1930s. Our grandfather had more or less left the company in the early 1920s, but had retained company stock; our mother sold some in 1951 upon our father’s death.

Giuseppe’s sixth son, Petrakaki’s brother Jacob (1833-?), gained some renown in the 1890s when he took over Smyrna’s commercial listings, an important resource for analysing the city’s economic growth. His son Oswald followed in his father’s footsteps in Egypt where he established the commercial listing and carpet selling businesses that had made the family so successful in Smyrna. Giovanni, our grandfather, was the youngest of the nine children Petrakaki had with Maddalena Dracopoli, another Chian 8 years his junior.Giovanni never knew his mother, who died from a hemorrhage, one day after his birth, in January 1869. Caro line Romano (1831-1904) became his stepmother, although her name appears on official documents only beginning in 1882. Petrakaki’s second wife, also a widow was a mere three years younger than he was. Giovanni may have felt deprived of maternal affection. As far as we know, his relationships with his brothers, especially Herman, were cordial enough, but he was not very out-going and was quite prone to depression. |

Maddalena Dracopoli, Petrakaki’s first wife |

|

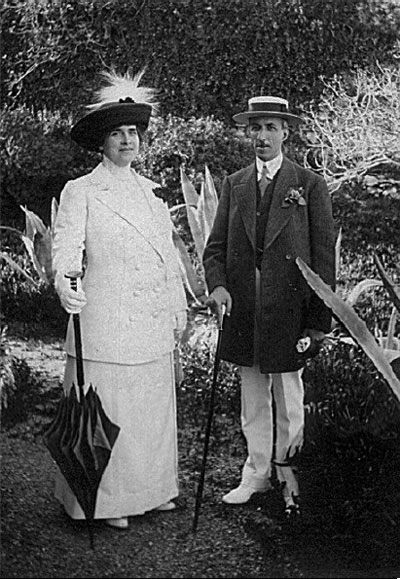

Giovanni (John) with Marie Guys. |

Like his brothers, Giovanni was active in his father’s business. As a young man, this took him to Iran (at the time, Persia), where his caravan once repelled a bandit attack. In 1896, he was married in the Smyrna’s new St. Jean cathedral to Marie Guys whose family of French merchants had been living there for over a century. Three years later, Giovanni and Marie joined Herman in Constantinople, who had moved there in 1893 to open a branch of P. de Andria & Co. They travelled with Herman’s wife, Helen née Edwards, and his daughter Margherita, called Rita, and their own two children, Marie-Jeanne and Mario Oscar, born in December 1896 and August 1898, respectively. The boy’s first name was specific to the branch, while his middle name was common among the Guys. A Giovanni and Marie’s third child, Stéphane Herman, was born in Constantinople in 1900. According to family tradition he was given the first name of Stevanachi/Marachi, and his middle name after his uncle and godfather’s, Herman. Uncle Herman eventually became one of the main managers of OCM and the administrator of Tombak, the Ottoman Tobacco Company. In the 1914 Ottoman business address list, Herman’s official address is on Misk street, in Pera, near Taxim; whereas, John (Giovanni) is not listed. Both names do appear, accompanied by the reference: de la maison P. de Andria et Cie [of the firm P. de Andria & Co.] and the company itself still appears at the Kutchuk Ismaïl Pacha address, on the other side of the Golden Horn, near the second bridge. Like Stéphane and a bit before him, Fred, Herman and Helen’s son, was born in Constantinople. The five children most probably grew up together and saw each other often. They would be reunited much later, in France14. |

|

Fred and Rita are Herman’s children. This picture was probably taken around 1907 in Constantinople.

The family travelled throughout Europe. The boys completed their education in Switzerland15. The Ottoman government’s decision in 1911 to deport Italian citizens following Italy’s attack on Tripolitania likely led, in 1913, to a prolonged stay in Ouchy, Switzerland, and Biarritz, France. Giovanni and his whole family were Italian, even though it seems they spoke French or English –and probably Greek to the domestic staff– rather than Italian, which the children hardly knew. They eventually returned to Turkey, and Giovanni was godfather at his niece Ignazia’s (Inès) christening on 13 August 1913 in Smyrna.

In 1915, the Ottomans and Greeks entered the First World War and took opposite sides in the conflict, the former allied with the Germans, the latter with England and France. I assume that, upon Italy’s entering the war that same year, also on the side of the Western Powers, the family left for France the region where their ancestors had lived for three and a half centuries, this time for good.

2 The “Corpi family is one of the oldest Latin families that made up the Genoese colony in Chios” (Episcopal attestation from April 6 1826).

3 Allotius (1587-1669) was a Chian Catholic clergyman of Greek origin, who was very knowledgeable about Greek and Latin, as well as Orthodox and Roman Catholic liturgies. Librarian at the Vatican, he bequeathed part of his inheritance to the Greek College.

4 The Marcopolis were one of the Genoese families residing in Chios. Considered to be among the most distinguished, esteemed and respectable, they married not only their peers but also the noblest families in Chios (Episcopal attestation from August 26 1826). Many Marcopolis were physicians.

5 A Smyrna family was bearing that name.

6 This caused erroneous interpretations, particularly concerning the age of the deceased.

7 I have not yet been able to specify the date on which this distinction was awarded. Its existence is proven by the ‘Cav.’ placed next to the mentions of Gio. Batt. in official documents. It might merely be the appointment to the rank of Knight in an honorary Sardinian order.

8 Marie-Carmen Smyrnelis, Une société hors de soi. He is listed for instance in the 1896 Smyrna directory as a partner in the Hamidiye ferry crossing company.

9 The de Portu family, settled in Chios since the beginnings of the Genoese colony, has produced a line of notaries and episcopal chancellors.

10 Nantes, Smyrna chancellery - Register 1856 N° 1.

11 Frangini writes “il padre liquidò e rimasto solo nella ditta” when Petrakaki’s sons start to join the company, meaning maybe that he had to liquidate his assets to push out A. Giraud, before starting a new company with the same name.

12 Where it was noted: “P. de Andria & Co – A splendid collection of Turkish carpets, excellent in style and quality”.

13 Herman was a key player in the building of this corporation, as can be seen in a letter of praise and thanks which arrived with a diamond brooch, a gift for his wife Helen, and was signed by the other members of the board. As early as 1913, Nelson asked to withdraw from the board of directors he had chaired. The arrival of Edmond Giraud, which coincided with Nelson’s departure, sealed the growing British influence in the company.

14 Herman’s children Rita and Fred kept in touch for a long time with their first cousins with whom they had spent their early childhood. Fred married Esther Donnet, daughter of the car (and hydroplane) maker who went brankrupt in the late 1930s after building the Nanterre factory eventually taken over by Simca.

15 Oral testimony from Stéphane.

Note: Mr D’Andria continues to research his family history and would appreciate any information to aid that project through: jfdeandria[at]sfr.fr.

A 5 and 6 generation alternative simplified charts showing how Jean François d’Andria is related to fellow contributor Bernard d’Andria.

A chart showing the ancestry of Jean François d’Andria going back 5 generations on both sides of his lineage.