As one author once wrote, any kind of reality is meaningful as long as there is a single person alive who is able to perceive it1. The same supposition can be valid for the notion of time, since time is also meaningful as long as it is perceived for what it is, and human perception of time tends to be shaped by the same practical and emotional needs that can be found anywhere regardless of the culture one is born into. One of those ‘needs’ is the need of commemorating a common past or belief of a certain group of people through a ceremonial celebration, and to pass it on to future generations. In that respect, ‘sessions of collective remembrance’ (e.g. religious holidays, carnivals etc.) that can be considered the means to measure ‘time’, also stand out as one of the most intrinsic elements of a traditional societal texture.

Assuming that the above statement is true, one can see a few reflections of a transition from traditionalism to modernity in our modern-day societies by looking at the fluctuations in observing the holy days and carnivals. Thus the fade away of Easter carnivals in Izmir leads us to further questions. Those who often remark, “Where are the (old) holy days today?” or “Where are the (old) carnivals today?” actually talk about the same thing. At a point where such complaints start to indicate something else, there unveils the unique and long-neglected socio-historical character of Izmir.

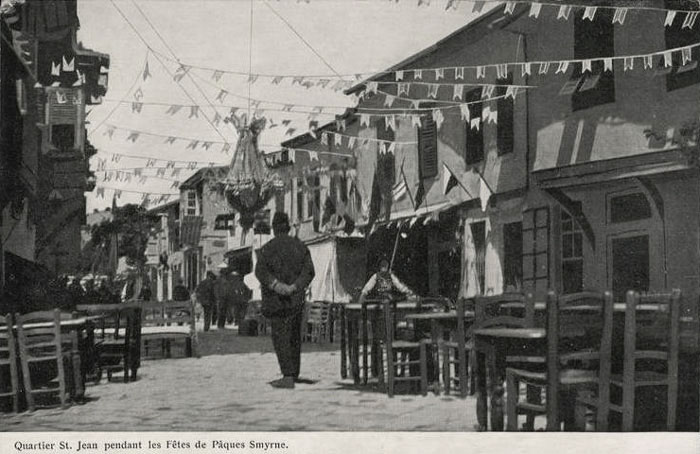

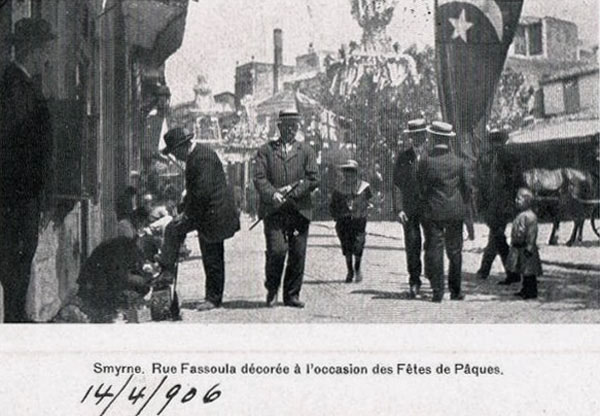

The carnivals of this once multi-language, multi-religion and multi-cultural city were not only a common entertainment for its inhabitants once but also had served as an insight into the life there for the visitors of the Levant through the 18th and 19th centuries. It would not be wrong to claim that the carnivals that were told either in an appreciating or disdaining manner (but never disregarded) by those travellers through the pages of their memoirs had started to materialise, as the demographic structure of the city went into a radical change. The impetus of this change without a doubt was related to the state the city had begun to enjoy as an economically growing port city and a flourishing place of attraction, starting from the late 16th century. It is no surprise that the improvement in the city encouraged traders from ‘72 different nations’ to surge into the city, and eventually caused the Western states to open their consulates there, accompanied by the arrival of monks in their robes2. The fact that the city had become the arena of competition firstly among the Catholic French and then Orthodox and Protestant missionaries can be seen as one of the indicators of such a progress in the city.

Relying much on the ideological and international conjuncture of the time and to the fact that there were upheavals due to epidemic diseases in the demographic structure of the city, the Jews, Latin Catholics, Armenian Gregorians3 as well as Armenian Catholics4, the Greek Orthodox; in fewer numbers English, American, Dutch and German Protestants, along with Muslims, had organised fundamentally as religious communities, forming a colourful societal composition in the city after all. Starting with the efforts of Mahmud II who was known as the gavur (infidel) sultan, and especially with the enactment of Hatt-i Sharif (Imperial Edict of Reorganisation) in 1839 which brought the non-Muslims of the Empire into equality with Muslims on common social and legal grounds, more and more reflections of the spiral evolution from traditionalism to modernity in the 19th Ottoman society started to get visible in many aspects and within each community - most prominently among the non-Muslims.

|

|

It would not be wrong to claim that the time of the year that spans from Christmas to the Resurrection Day in April (aka Easter), encompassing a series of holy days in-between, had a disuniting effect rather than unifying on the non-Muslim communities of Izmir. Because every community had its own calendar, meaning some used the Julian calendar and for the others, it was the Gregorian calendar; and the eleven day discrepancy between the (354-day) lunar year and the (365-day) solar year would cause overlapping of the carnival dates of respective communities each of which would correspond to a different time of the month. On the other hand, it is likely to think that the Roman Catholic Church could have initiated a new calendar configuration, bearing in mind that the Easter of all Christians (after the 40-day long fast that also followed the 3-day Carnival ‘Apokries’) could coincide with the Pesach (Passover)5 of the Jews.

Seemingly, one could easily observe the minor projection of a wider scale phenomenon of inter-religious or inter-denominational conflict that took place in Izmir during the carnivals, and that must be quite a dynamic scene. It is known that the ‘Carnival Season’ in Izmir used to cause serious concerns over security until the 1890s in the city, and the major reason behind that was the exuberances of Greeks and their ‘blood feud’ with Jews which would reach to its highest level during the Easter Carnival. Reportedly there used to take place various scenes among Greeks and Jews some of which eventuated in homicide, because of an assertion that a Greek boy was allegedly kidnapped by a Jew and the Jews added his blood into their matzo for Jesus Christ’s blood during their Passover which collided with the Greek Easter, and such incidents would happen over and over again every year. An observation by a German traveller Ernst Christophe Döbel written during his visit to Izmir in 1832 serves as a relevant evidence for the past existence of such incidents:

“…Even the slightest argument would be enough to get to feel the coldness of the Greek knife on your skin. Such events were so endemic during carnivals that you could find many dead or wounded men on the streets...”6

The fiercest of such conflicts it seems takes place in 1872 and the daily newspaper La Turquie reports: “It is an event that brought the Middle Ages back to our city,” - recalling the times of the Inquisition. According to the news article; two people died and twenty of them got wounded as a consequence of a quarrel between the Greek and Jews, fuelled by the Greek accusation of Jews of a drowned child found in the sea.7 Perhaps not as violent as that, but throwing away dry beans or pouring out boiling water over the people were among the frequently used methods that would cause serious injuries, if not death, and of course keep the security forces busy.8 Public security problems start to diminish with the founding of the municipality organisation in 18749, especially during when Midhat Pasha (1880-1881), Halil Rifat Pasha (1889-1891) and Hasan Fehmi Pasha (1893-1896) were in the office of governorship.10

Against all odds people never stop enjoying their time on the streets during the carnival time. Another traveller that witnessed the carnival in 1831 describes it with expressions of both admiration and disdain:

“...Carnival time happens to be a season of joy and delight to which various communities from Izmir contribute with the same degree of eagerness. Concerts, balls, theatrical shows come one after another rendering it impossible for the public to be indifferent to them... During the carnival time one can see the crowds in their absurd clothes rush toward somewhere, something to pay visits or just not to miss an amusing show. Even the seldom-speaking, sober-minded Turks seem to receive their share out of this collective ecstasy”.11

Not all the travellers shared such statements of admiration. For instance an English traveller, who made his way to Izmir between 1810 and 1817, describes a carnival he witnessed as following:

“…There is no such masquerade as the parade toward the end of the carnival. I saw an impersonated Bacchus seated on a wine barrel with several taps on it. On the same coach there was a crowd of miserable looking people with wilted leaves and flowers stuck on their bodies, playing and dancing to music, who looked like flesh coloured puppets to me.”12

Greek men generally preferred the zeybek costumes which allowed them to carry a gun or a dagger on their waist, making it no coincidence that they wore such outfit by the time of the Greek War of Independence. Greek and Armenian women, on the other hand, used to prefer wearing more ‘oriental’ looking clothes. A traveller named Ludwig Ross who visited Izmir in 1845 gives us detailed information on that:

“…Franks have the kind of parties in their houses that they were accustomed to back in their homelands... Associations like Casino Europeo, Casino Greco, Cercolo Levantino organise the festivities for them. There are a reading room where various local and foreign newspapers are provided, a ballroom for regular events and a couple of card game rooms in each casino. Young girls and ladies who wear their loveliest dresses and put on accessories keep the glory of the Ionian woman alive especially at the balls given during the carnival. Three or four lines of seats from the walls of the room are filled by Armenian ladies with their bright eyes and glittering skin, along with beautiful Greek ladies and the mixed-blooded Levantine ladies with Armenian or Greek descents originating usually from the mother’s side as of the last few generations. The main fashion inclination among young women is contemporary French fashion. Seemingly, Armenian and Greek ladies have not dropped the habit of wearing their short embroidered jackets with full sleeves -which is an oriental piece of garment- and the tiny fez with fringes on its side which is a characteristic Izmir garment, whereas men only prefer black tie. Only exceptions to their uniform approach are when the Turkish men or the naval officers enter the ball room. The most colourful and joyful balls are given by the Greeks and the Levantines. Ladies dance in all three of the casinos all night long. The balls normally start at 10 pm and last until 7 or 8 in the morning.”13

As stated above, customs of celebrating the carnival are quite different among the high life circles where the state of welfare is higher than the rest of society and that indicate a class distinction between certain groups of society. Levantines who consider themselves Europeans hold a bigger economic power and prefer enjoying the carnival time in eminent clubs and casinos unlike the Greek rowdy who takes up the streets instead. It is an ordinary scene though, to see the socioeconomically advancing Greeks and Armenians join Levantines in their clubs during the Western Easter, especially when the date of the Orthodox Easter coincided with the former. Such clubs and casinos used to function with the principle of membership until almost the last quarter of the 19th century, and enjoy a highly aristocratic quality. So it was not common before then to see people from lower classes being accepted in such places nor was it deemed respectful that the club owners do so. Similarly, a statement from the daily Stambul on the date of February, 1876 goes: “It seems like it is commonplace now for many to enter such places where very few people were allowed in the past.”14

Although Muslim (the ‘predominant group’ of the Empire) guests have been invited to the balls out of politeness ever since they were held, only toward the end of the 19th century did the modern and casual Muslim families start to attend the entertainments, and this tells gives us a clue about the loosening of the strict borders between communities. Around the same time, the governorship of Hasan Fehmi Pasha (1893-1896) sees the coming into effect of interesting implementations in Izmir like the ban of Muslim men’s wearing traditional baggy trousers – şalvar and a new dress code, as well as strict precautions being taken for a safer carnival time, and that way the ‘sober-minded’ part of society begins to escape its traditional attitudes little by little. Perhaps the biggest problem Muslims suffered during the days of Christmas, Easter and the Carnival was that the non-Muslim bakers did not used to open their shops on such days and the Muslims were being left with no bread to eat. The then chief secretary of Izmir governorship and subsequently a member of the Ottoman Assembly Kamil Dursun, writes to his journal that Muslims used to store bread to consume during the Christian holy days before they arrived.15 The reason why non-Muslim bakers abstained from opening their shop on holy days is that for both Greeks and the Jews it was regarded reprehensible to make bread on such days.

Another significant element of the Izmir society, Armenians, used to do more plain celebrations than Greeks did and the rituals of Armenian Catholics resembled to that of the Levantines. In the issue of the Stmabul newspaper dated February 7, 1876, a scene from that year’s carnival is portrayed as following:

“Unlike the Greeks who enjoy carrying guns a lot, Catholics, with their peaceful nature rarely wear zeybek costumes. They mostly like wearing clown costumes, putting on clown makeup, growing sideburns and putting up strange hats up on their heads that made them look like the Englishmen. There is a tendency among the Armenians in the last few years to masquerade as such at the carnival time.”16

The pomp and grandeur of the carnivals that catches the attention of even the newspapers from Istanbul owed undoubtedly to the socially more liberal and indulgent regime Tanzimat has secured, adding a distinctive dimension to the celebration of the holy days.17 However, it should still not be overlooked that though the ruling class approached such religious rituals as a means to harmonise in conjunction with the liberated, gratified and integrated individuals of the Ottoman society, the holy days and festivities also helped the subject communities to build their own ‘national’ identities. To evaluate better the journey of the carnival tradition across Izmir, I would like to focus on under what kind of circumstances the carnivals endured throughout the 20th century in the light of my personal accounts of the Levantines staying in Izmir.

As of the 19th century modernity has largely meant anything and everything related to the nation-state, within and beyond the borders of the Western world. So, the question is: what sort of sentiments non-Western societies were supposed to cling to at the time? When looked at the Ottoman society of the time, we instantly comprehend that Muslims were the dominant group and at ease in that respect -except the fact that they had to save their land from the foreign interventions which was not at all an easy job- meaning that they at least had a state, although it was not nation-state, that they felt belonging to. The problem was rather the sense of community amongst non-Muslims. The cases of non-Muslim communities like Greeks, Armenians and Jews who were considered the Ottoman subjects within the millet system, and that of the ‘foreigners’ (in this case, ‘aliens’) and of the Franks were incompatible with one another, in the sense that the latter two ones had not suffered from any sort of anxiety of belonging as they had initially organised as communities around the consulates of the Western states, whereas the Levantines who were estimated as ‘foreigners’, though some of them were Ottoman subject, had a complex status. Seemingly, there were serious competition and conflicts between those who had been living in Izmir for the last three generations when more Europeans entered the city roughly in the 1840s. ‘The anxiety of belonging’ became the case this time for the Levantines who were long based in Izmir with the wave of European influx into the city, because until then, veteran Levantines associated themselves with Europeans and now the new-coming Europeans were ‘despising’ them by calling them the ‘Hellenised Europeans’. Probably the reason for such a disdain was the fact that the Levantines had made substantial marriages with the local Greek and Armenian women.

Around the same time spread a new idea through the hybridised Levantine circles: building up a city-state under the control of Greek-speaking Catholics. Towards 1860, Levantines from Izmir, especially the ones who spoke primarily Greek, turned their back to the countries they traditionally depended on, i.e. France and Vatican City. In 1862 they declared their aim to build a city republic of their own, which actually meant the founding of an Aegean Federation. However, the European states, pre-eminently France, did not like the idea and suppressed the local initiation in collaboration with the Ottoman state.18

That way Levantines who could not attain their aim developed a double face identity: outwardly they pretended to fulfil anything required to look loyal to the European nation-states/authorities so as to guarantee the sustenance and preservation of the capitulations, and on the inside, harboured a faith-based post-national identity. Just in that way they managed to get perfectly integrated into the socio-political thinking of the Ottomans which classified the citizens according to their faith.19

Yet that double face identity of theirs started to cause them to get often caught between two fires, as much as it was an advantage for them: Major European powers in the age of intense nationalism were expecting full allegiance from their nationals around the world and the Ottoman leaders of the Progress and Union Party that took over the government in 1908 started to increase pressure on the ‘foreigners’ whom they saw solely as the benefiters of capitulations, which was a view in line with their future plans of abolishing the grants of trade privileges that the Levantines enjoyed and nationalising the economy.20

Levantines who owned Italian passport became the first in the community to face the tragedy of being the target of such political decisions. The Ottoman Empire went to war with Italy in 1911 and did not allow the Levantines who were Italian nationals to stay in the Ottoman country until the war ended. Smyrniots were no exception to that order. Most of the Levantines from Italian origin had to leave the city and took refuge in Italy, a place they did not really pertain to, whereas those who did not want to leave Izmir denied their nationalities and became Ottoman citizens. After Italy won the war, the ‘renegades’ who stayed in Izmir had hard times to explain the official at the Italian Consulate how they ‘lost’ their nationalities during the war.21

The life conditions in Izmir during the years of the Balkan Wars, World War I and the War of Independence which came one after another resulted in a gradual loss in the value of inter-communal relationships which were not handled very closely but at least side by side in peace for many years. For instance Muslims started to accuse their Greek Orthodox fellow townsmen of arrogance and betrayal for their actions during Easter only then, seeing them as the expressions of loyalty to the Greek state but not to the Ottoman one. As years passed, it got more and more obvious to Muslims’ eyes that the pauses in daily life on Christian’s holy days were proving the Greek and Armenian domination in city’s economic life and Muslims were not ignoring it as they once did.22 So much so that it has become the case that Muslim kids started disturbing the ‘gavur’ during their festivities. I would like to exemplify it with two testimonies from the oral history research we conducted in and around Izmir some time ago. Idris Karaduman, born in 1906, tells about an innocent molestation:

“They used to call it Easter then. Not sure if it was before our Hidirellez though, but anyway, they used to have an egg thing. That was when we used to stand at our doorways in order to scratch gavurs’ legs with a bunch of stringing nettle in our hands as they passed by our doors.”23

Şükriye Elham (b. 1910) gives a more ‘feminine’ account:

“…We used to live in a house across the police station in Çorakkapı (Basmane). I used to have Greek and Jewish friends. There was a girl called Judith. One day she said ‘The Turks are mad people’. I was in the 5th grade or something and I said: ‘I will show you the mad Turks’. It was the Passover time. Jews had cleaned up their houses. I called my cousin Hilmi to come to our place. I took a paper bag and filled it with crumbs of bread. I told Hilmi to go to Judith’s place -their door was usually unlocked- and spread the breadcrumbs into the house from the doorway. He did as I told him and made sure that their house was full of bread all over the place. They had to sweep around the house over again.”24

Yet the Muslim perception of the Levantines was never that negative, what is more, it tended to get better as they took side with the Ottoman government during the Greek occupation of Izmir. This time they were at the winners’ side. Let alone to be forced to leave the lands that they lived and worked on, -Armenians and Greeks were forced to- Levantines enjoyed the absence of the ‘palikars’25 whom they viewed lower-class competitors. However, that relief did not last much long, because the newly established republic was carrying along the same nationalist economic policies the previous governance did. As a result of both that and the Turkish-Italian tension in the 1930s, all the Levantines regardless of their nationalities as well as the Jews got excluded from certain fields of work so as to open the positions up for the Turks. At the expense of building a Turkish nation-state, authorities closed their eyes to the departure of many Levantine and Jewish families from Izmir, yet for some, Izmir was too special a place to leave, so they stayed. However, thenceforth lived as rather withdrawn communities whose members were tightly connected to their faith and their family bonds…

In the meantime the carnivals which used to help the community get together and regenerate the religious identity started to get celebrated indoors and to serve this time as ‘collective sessions of remembrance’. The three photographs, one being probably from the early 1930s, and the other two being from the year 1936 and the 1950s respectively, show that the carnival tradition was still vivid back those years.

We see Eugenie Kokini (b. 1906) and her husband together with their friends in the first photograph, probably taken in a photo studio in the early 1930s. The couple looks quite different among the others with their ‘oriental’ outfit. Eugenie’s husband is in a zeybek costume which was preferred mostly by the Greek rowdy in the old times, however misses a dagger on his waist and Eugenie looks rather like a typical ‘oriental’ lady than a Levantine in both the first and the second photographs with her red baggy trousers (the photograph is coloured later in the original style), a red bare-shoulders strappy bustier, ankle-strap peep-toe high-heel shoes, embroidered tulle headscarf, snake-bracelets on arms and two strings of pearl and wooden necklaces around her neck, while the others conformed to the Western wardrobe.

|

|

In the third photograph from the year 1936, we see Eugenie together with three of her women friends entirely in Western style clothes. The concept of this one is distinctly Spanish; that is why the skirts are longer and fluffier as they are worn over a crinoline, accompanied by a trendy headband or an artificial flower over the head. Unfortunately we do not have any information about whom these dresses might have been sewn by. It was probably themselves or a casual tailor who sewed them after studying the European fashion magazines of the time!

|

A photograph from 1948 shows a delighted ‘Spanish woman’ dancing with her cross-dressed partner and another photograph from 1952 depicts a 46 year old Eugenie Kokini posing like a little school girl with a ribbon on her head and her white socks.

Eugenie Kokini (1948)

|

Eugenie Kokini (1952)

|

The last carnival photo dating probably back to 1950 shows her in quite an aristocratic Parisian look with a monocle in her hand. The same photograph features some of her children next to her in their special costumes.

|

A similar photograph of the Kopri family from Karşıyaka dates back to either 1959 or 1960. This time all children are in carnival costumes: Japanese, Gypsy, Indian looks as well as mouse and rabbit mascot costumes are distinguishable. Interestingly, this carnival is said to be celebrated in Architect Abdullah Bey’s house located on a street called Blue Corner that is still known with the same name by many of the old residents of Karşıyaka. This photograph also gives us the impression that the tragic memories of September 6-7 are almost overcome and a Muslim fellow can have his non-Muslim friends celebrate their carnival at his house without taking a notice of the ‘nationalist’ fuss around. It may not be right to draw such a conclusion but this little piece of information that we know is worth being mentioned as a significant improvement of its time.

|

The photo album from the period of time between 1950 and 1980 by Pierre Murat who has entered the Kopri Family in 1948 as their groom covers as colourful scenes from the carnivals as the ones pictured above. We can see Pierre Murat in his photos from the 1950s in the looks of an English lord with his exceptional hat and of a beggar with canvas clothes, respectively.

|

|

It looks like it was almost impossible to challenge those costumes that the ‘Upholsterer’ Pierre Murat designed and tailored himself making use of the leftover stuff found in his workroom. Here is an important point: One of the most prominent characteristics of these carnivals is that the participants have to wear catchy and absurd costumes. Pierre Murat is absolutely one of those who did it quite rightly. He had competitors, though. For example we see Basil Kopri in cowboy clothes in one of the photographs from the late 1970s. Funny enough, the thing he put over his head for the cowboy hat looks like an upside down baby potty seat! In the same photograph, we see Pierre Murat having dressed like a woman in white clothing and smiling happily along with his childhood friend Ivan who is standing next to him and wearing a clown hat.

|

Apparently Pierre Murat and his friend Ivan were the wicked duo of the carnivals back in their youth. One of the tricks they once did to make the carnivals all the more memorable and enjoyable can give us an idea about how wicked they really were:

“My mate Ivan... We were childhood friends. We celebrated many carnivals together. We used to wear a different costume in each carnival... Costumes of ballerina, princess and so on... Everybody had to think of some costume and then wear it! Once we had a brainstorm thinking what to wear and decided on making a horse! We bought some sticks and made a square out of them to form the horse’s body. Next was its head. It suited my head... So we made two holes for the eyes, painted a nose... Not sure though, whether it looked like a horse or a mule! Anyway I put it on, and Ivan was supposed to wear its back... We found also a tail... All was done but something was missing... We had to something else. We bought a chocolate cake with cream in the middle. We cut it into two transverse pieces and put onion, pepper, garlic, and the other sour stuff we could find into it and closed it up. We made four or five cakes like that and put them in a carton box. Anyway, Ivan held the box behind me in our horse costume and put down the cakes on the ground one by one as if the horse was defecating! Prior to our show we have told a friend about our plan and warned him not to eat the cakes but hand them to the people around. So, we started to put away the cakes... People threw up as they ate them... We had died laughing! You must have seen how many people took a bite of the cake...We used to do things like that…”26

|

Sadly enough, the habit of celebrating the carnivals mostly at Pierre Murat’s place and more seldom at the Lili Marleen Casion once located across the Karsiyaka Pier on the way to Alaybey, stopped all of a sudden in the 1980s. It is unknown to what extent the military coup of 1980 had an effect on that, but it is for certain that Pierre Murat’s loss of his wife at the time played a huge role in its coming to an end. Pierre Murat loses not only his beloved wife Otilya but also his joy and passion in life with her death. He does not host any carnival celebration in the following 20 years. We do not have any information about whether the Levantine families of Izmir found the other ways of celebrating carnival in this time period. I am happy to announce that Pierre Murat resumed the tradition of hosting the carnival at his place in 2002, this time entertaining also Muslim guests like me. However, there remain two points that he complains about: firstly, the lack of enthusiasm among the participants of the carnival and secondly the fact that they do not wear special costumes as once everyone did. He is right. It is sad but true that one cannot help but yearn for the old carnivals after looking at the old photographs.

|

Despite the fact that there are different views on the etymology of the word27, it is widely believed that ‘carnival’ derived from the Latin phrase ‘Carne Levare’ meaning ‘taking away of flesh’.28 In other words, after 40 days of fasting and abstaining from eating meat and the other joys of life, people were supposed to recreate themselves during the carnival. There are various views on its origins but the general opinion is that carnivals dated back to pagan times and stood for celebrating the fertility of the harvest and the coming of spring. On the other hand, carnival also means the temporary suspension of conforming to the basic codes (e.g. laws, bans and legal limitations) that shaped the order of the official or hegemonic social life. That way people who were traditionally separate from one another in daily life due to the hierarchic obstacles that did not let heterogeneity expand much, could come together in the more independent and informal atmosphere of the carnivals.29

It is comprehensible that carnivals, just like holy days, can normally go into a transformation in time in terms of meaning, style and content. Yet it is completely a different and a tragic thing that a society loses its carnivals for good. And in our case, it is much more a tragic event if it happens in a part of the world like Izmir, where people almost have a genetic impulse to get together all the more freely and familiarly...

|

Dr. Pelin BÖKE, Ege University, Department of Atatürk’s Principles and History of Turkish Revolution

2. Though the presence of Christian missionaries in Izmir dated back to 15th century, its density increased mainly in the 19th century. (See Konstantinos Oikonomos-Bonaventure F. Slaars [2001], Destanlar Çağından 19. Yüzyıla İzmir [İzmir: from the Age of Legends to the 19th Century], Istanbul: İletişim Publishing, p. 229).

3. Armenian Apostolic Church is one of the early churches that traces its historical origins back to the times of Jesus Christ and asserts a status of ancientness. One of the basic customs of the church is that it credits Jude the Apostle (Thaddeus) and Saint Bartholomew who was the two of the Twelve Apostles as patron saints. Armenian claim is that they are the first nation on earth to adopt Christianity as their official religion. Historically, the first religious leader of this movement was Saint Gregory the Illuminator (Grigor Lusarovich) who was brought up in Caesarea (present day Kayseri in Turkey) as a Christian and then converted Armenia from paganism to Christianity. His followers to this day are known as Gregorians. (For further information see Prof. Dr. Abdurrahman Küçük, “Gregoryen Ermeni Kilisesi’nin Oluşması ve Konsil Kararları Karşısındaki Tutumu” [Founding of the Armenian Apostolic Church and Its Attitude towards the Council Decisions]. According to a population survey done in 1911, 9.656 Armenians and 523 Armenian Catholics lived in Izmir. Presumably, those who were not Armenian Catholics were Armenian Gregorians. (See Hüseyin Rıfat [Işıl] [1997], Izmir 1914, edited by Erkan Serçe, Izmir: Akademi Publishing).

4. After the conflicts between Armenian Gregorians and Armenian Catholics reached to an extreme level, Mahmud II issued an imperial order to deport the Armenian Catholics from Istanbul and Ankara to provincial Anatolia on 10 January 1828. During this migration, which is known as the first deportation of the Ottoman Armenians, it was probably the case that a number of Armenian Catholics had moved to Izmir. (For further information, see: Kemal Beydilli [1995], Recognition of the Armenian Catholic Community and the Church in the Reign of Mahmud II. (1830), Cambridge: Harvard University Press; Davut Kılıç [2006], Osmanlı Ermenileri Arasında Dini ve Siyasi Mücadeleler [Religious and Political Conflicts between the Ottoman Armenians], Ankara: Atatürk Research Centre).

5. The religious holiday that symbolises Israelites’ Exodus from Egypt and their emancipation from enslavement. (On how such special historic events are remembered by societies, see Paul Connerton (1999), Toplumlar Nasıl Anımsar [How Societies Remember] Istanbul: Ayrıntı Publishing, p.73).

6. İlhan Pınar (1994), Gezginlerin Gözüyle İzmir: XIX. Yüzyıl (19th Century Izmir through the Eyes of Travellers), Izmir: Akademi Publishing, p.19.

7. Rauf Beyru (2000), 19. Yüzyılda İzmir’de Yaşam (Life in Izmir in 19th Century), Istanbul: Literatür Publishing, p.151.

8. Henri Nahum (2008), “Bir Fotoğrafa Bakarken: 1900 Yılında Smyrna’da Bir Yahudi Ailesi” (“Looking at a Photograph: A Jewish Family in Smyrna in the Year 1900”) in İzmir Unutulmuş Bir Kent mi? (1830-1930) [Smyrna, the Forgotten City? (1830-1930)], Ed. Marie-Carmen Smyrnelis, Istanbul: İletişim Publishing, p.116.

9. Erkan Serçe (1998), Tanzimat’tan Cumhuriyet’e İzmir’de Belediye (1868-1945) [Municipal Government in Izmir from Tanzimat Era to the Republican Era (1868-1945)], Izmir: Dokuz Eylül Publishing, p.54-55.

10. Cana Bilsel (2008), “Modern Bir Akdeniz Metropolüne Doğru” (“Towards a Modern Mediterranian Metropolis”) in İzmir Unutulmuş Bir Kent mi? (1830-1930) [Smyrna, the Forgott City (1830-1930)], Ed. Marie-Carmen Smyrnelis, Istanbul: İletişim Publishing, p.158.

11. Beyru, ibid, p. 331.

12. Beyru, ibid, p. 331.

13. Pınar, ibid, p.96.

14. Beyru, ibid, p.334.

15. M. Kamil Dursun (1994), İzmir Hatıraları (İzmir Memoirs), Ed. Ünal Senel, Izmir: Akademi Publishing, p.3.

16. Beyru, ibid, p.333.

17. Sibel Zandi-Sayek (2008), “Bayramlar ve Tören Alayları: 19. Yüzyılın İkinci Yarısında Ritüel ve Politika” (“Holidays and Processions: Rituals and Politics in the Second Half of 19th Century”) in İzmir Unutulmuş Bir Kent mi? (1830-1930) [Smyrna, the Forgotten City? (1830-1930)], Ed. Marie-Carmen Smyrnelis, Istanbul: İletişim Publishing, p.185.

18. Oliver Jens Schmitt (2008), “Levantenler, Avrupalılar ve Kimlik Oyunları” (“Levantines, Europeans and the Games of Identity”) in İzmir Unutulmuş Bir Kent mi? (1830-1930) [Smyrna, the Forgotten City? (1830-1930)], Ed. Marie-Carmen Smyrnelis, Istanbul: İletişim Publishing, pp. 130-131.

19. Schmitt ibid, p.135.

20. Schmitt, ibid., p.136.

21. Schmitt, ibid, p.136.

22. Evangelia Achladi (2008), “Savaştan Yunan İdaresine; Kozmopolit Smyrna’nın Sonu” (“From World War I to the Greek Occupation: The End of Cosmopolitan Smyrna”) in İzmir Unutulmuş Bir Kent mi? (1830-1930) [Smyrna, the Forgotten City? (1830-1930)], Ed. Marie-Carmen Smyrnelis, Istanbul: İletişim Publishing, p.212.

23. İdris Karaduman (b.1906). Interviewed on January 26, 1999 in Karşıyaka/Izmir.

24. Sükriye Elham (b.1910). Interviewed on October 2, 1995 in Karşıyaka/İzmir. The aim of spreading breadcrumbs around refers here to the fact that Jews traditionally do not eat regular bread, but un unleavened bread called matzo, during their Passover and it is an act of ‘revenge’ on the part of Muslims in that respect. (More testimonies can be found published in a book by me. Pelin Böke [2006], İzmir 1919-1922: Tanıklıklar [Izmir 1919-1922: Testimonies], Istanbul: Tarih Vakfı Yurt Publishing).

25. Translator’s note: Greek militiaman who fought the Greek War of Independence (1821-28) against Ottoman Turks, or properly a lad who is a mix of a fighter, a patriot and a good-fellow.

26. Pierre Murat (b.1920). Interviewed on December 22, 1998 in Karşıyaka/Izmir.

27. There is another view claiming that the word ‘carnival’ derived from the Latin phrase ‘Carrus Navalist’ which literally means the ship or the chariot of God. (See: Metin And [1969], Geleneksel Türk Tiyatrosu [Traditional Turkish Theatre], Ankara: Bilgi Publishing).

28. Sevan Nişanyan (2002), Sözlerin Soyağacı; Çağdaş Türkçenin Etimolojik Sözlüğü (Geneology of Words: Modern Etymologic Dictionary of Turkish), Istanbul: Adam Publishing.

29. For further detail, see: Mikhail Bakhtin (2001), Karnavaldan Romana (From Carnival to Novel), Istanbul: Ayrıntı Publishing, p.238.

30. The above article is based on the submission by the author on the occassion of the Izmir Symposium ‘Körfezde Zaman: İzmir Araştırma Kongresi’ [Bay Times: Izmir Research Congress] held in December 2009 - flyer and translated (click to view original) here by Görkem Daşkan, 2011.