The Contributors

Noël William Cramer: Exploration of my Levantine roots and memories - version française

MY EARLY LIFE

Trabzon (1941 – 1951)

[“The breeze, having changed direction under the effect of the afternoon sun, once again brought back the scents of the sea and amplified the perception of the rhythmic beating of the waves. The gray dunes of ferrous sand hid from my eyes the city of Trebizond, a few kilometres away. In my opinion, the “Black Sea” must have been so called because of the colour of its sand. While my parents were resting in the shade of a shrub, I headed for the station of white lilies, the perfume and elegance of which I had apprehended at the start of our Sunday excursion, but the flowering, which was exuberant during our last visit, had wilted and the sand was sprinkled with large seeds, black and light as charcoal, heavily laden with memory...”.

Behind this simple memory of a moment experienced by a four-year-old child lie the principles that govern the movements of the wind, the sea, the radiation of the Sun, the plurality of chemical elements and their properties, the phenomenon of life and its reproductive cycles, the perception of our environment, as well as the interpretation that everyone can make of it according to their experience, and of “information”, a term widely used in contemporary thought, a difficult notion, inevitably placing those who persist in using it, at some point, in front of a mirror. But however banal the lived experience, its links with the Cosmos can be tangible, sensed intuitively by the one who seeks to look….]

These first lines of an essay written (in French: “L’Univers, le Naïf et la mémoire des graines”, dans La Différence, GHK, éds. 1995, Neuchâtel: Musée d’ethnographie) for JACQUES HAINARD of the Ethnographic Museum of Neuchâtel (Switzerland) summarize what was for me the beginning, and later the culmination of a way of seeing and understanding the world in which I had to live.

A few days before the beach was sown with my favourite flowers, my father had returned from his office with the newspaper which headlined the use of a terrifying bomb in the war between the United States and Japan. I can still see the scene where he was reading the article, in the small room adjoining the dining room which still let in the late afternoon sun, and commenting on the event. I couldn’t understand the meaning of what had happened, but I perceived its gravity through his attitude.

Understanding the World is essential to giving meaning to life - but can also serve to destroy it.

The gray sands of the Black Sea

These preoccupations did not concern me at the time - moreover I did not have many of them if my memories are correct - in my native town of Trebizond which then had only 30,000 inhabitants. Populated by descendants of the Greek colony founded in 756 BC, various passing sailors, Anatolian tribes such as the Laz, a few Armenians - and two European families: ours and that of the English consul, Mr. and Mrs. BREEN with their child whose name I forget. The latter had not started its second year, and was therefore devoid of interest for me.

Shortly after, Mrs. BREEN succumbed to the charms of a visiting Australian, Mr. MANNING, an adventurous but rather unscrupulous man who drove his Jeep recovered from the American army with immoderate speed on the stony roads. She flew with him to the antipodes. He must have had some hidden virtues because I watched my mother, horrified while nevertheless being fascinated by the character - detestable to my still objective child’s gaze.

The HARRIS couple then took over in 1949 and stayed there until the consulate closed in 1956. I liked them because they served me an excellent “Lime Juice”, which my parents were allowed to taste with an additive. My father often visited the Consul and held VORLEY HARRIS in high regard. His son, CHRISTOPHER, published in 2005 an excellent and very informative book on this last British consular mission in Trabzon: (The Reports of the last British Consul in Trabzon, 1949-1956 – a foreigner’s perspective on a region in transformation (edited by Christopher Harris), 2005, The Isis Press, Istanbul).

I briefly knew the last consul of France, the CAILHAUDs, and their son BERTRAND who was my age and with whom I remember having played. We spoke in Turkish, because I didn’t speak French yet. They left Trabzon in 1945.

Another Swiss family, the HAEGLERs, had left the city for Istanbul where their commercial activity was more profitable. Their son ROLF, the only other Westerner of my generation born in Trebizond to my knowledge, was four years older than me - so I saw him very little. We met recently and were able to compare more than six decades of parallel evolution. His sister GISELA was born in Istanbul and we met as friends in Zürich in the 1960s where she came with her family.

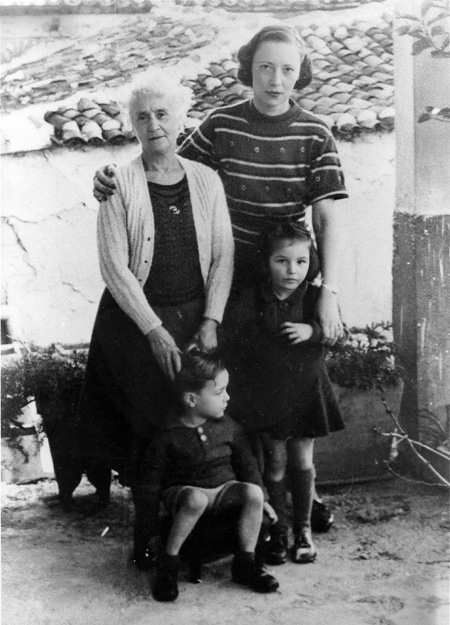

The HAEGLER family, with my mother (centre) and “ROLFI” (left) on their way to Istanbul. I wasn’t there yet.

Izmir (Smyrna)

In 1805, HANS RUDOLF CRAMER of Zurich married ERNESTINE WILHELMINE VON GONZENBACH, heiress of the Gonzenbach estate in Hauptwil in Thurgau. The family legend says that HANS was a great lover of “gambling” and financial speculation, and that his passion ended up seriously denting the resources available locally. But the in-laws, who had made their fortune in spinning, owned cotton plantations in Turkey and Egypt as well as spinning facilities in Izmir. This is how their son JACOB CHRISTOPH (my great-grandfather, 1816-1874) found himself comfortably established as a textile merchant in Izmir in Turkey around the 1840s.

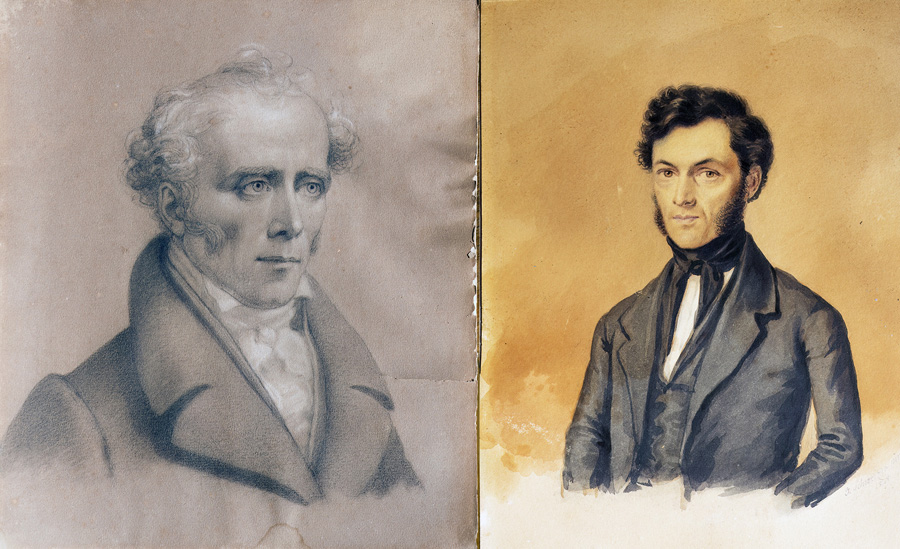

Mystery ancestors: These two drawings were on the wall of my grandmother Anna’s sitting room in Bornova. I remember them distinctly at that place. One of them can be even distinguished on the photograph on the wall of the Dip Sahrinch home when my father was working for the emery mine. I cannot unfortunately identify them. My grandmother used to say that the older person to the left had been “a mathematician”.

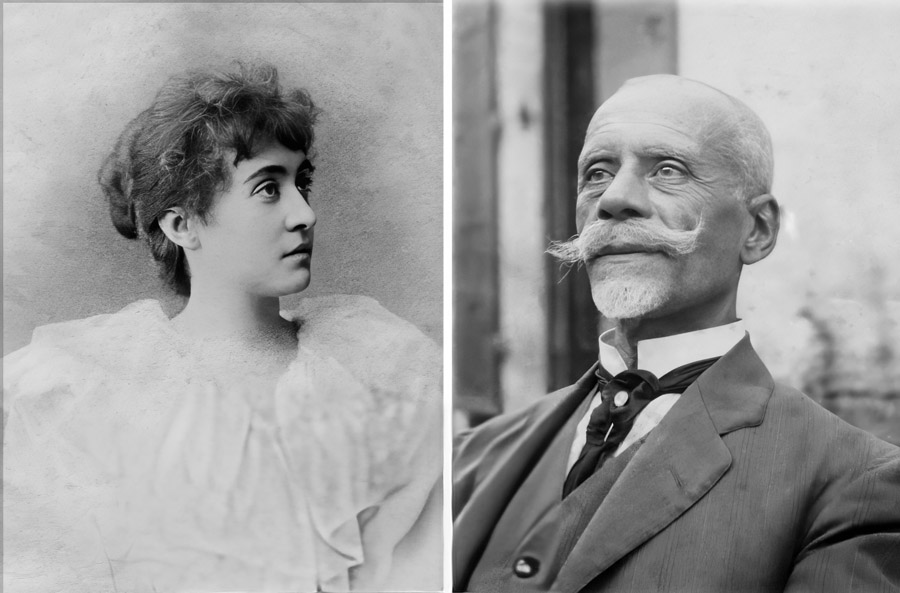

My grandparents ANNE MARIE born CHASSEAUD (images of her ‘Forget me not Autograph Album’) and HERMANN RUDOLF CRAMER

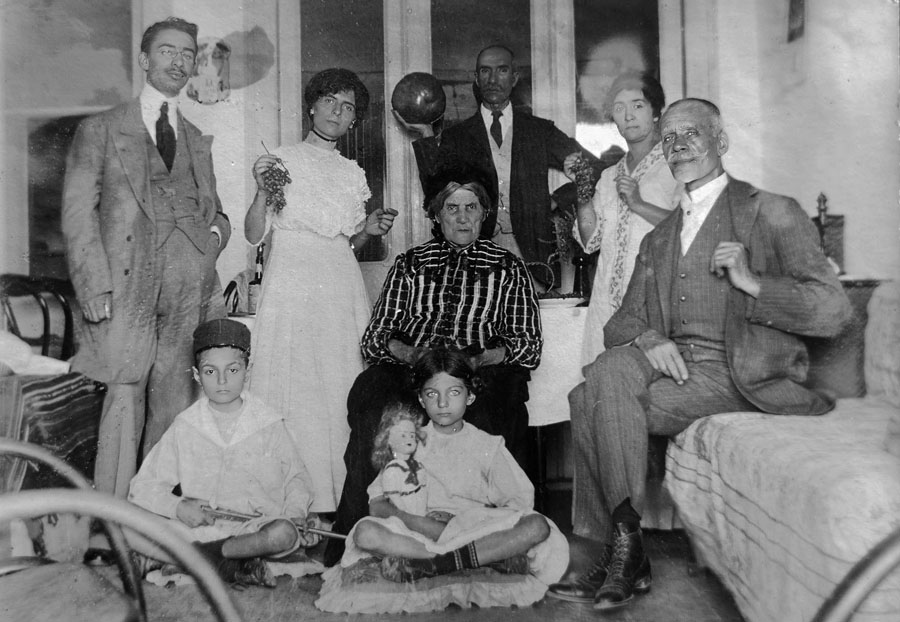

My grandfather and grandmother with their respective brother and sister in 1890-1900. To the right is Hermann Rudolf (my grandfather) and behind him Anne Marie (my grandmother, holding grapes). The man holding the watermelon is his brother Hyppolite Robert and Anna’s sister Sylvie Chasseaud (also holding grapes). Two brothers who married two sisters!. I unfortunately can’t identify with any certainty the old lady or the other person and the children, the location most probably being grandfather’s house in Bornova.

He had five children by his wife MARIA MORARY; two girls and 3 boys. The last two sons concern me more directly. HERMANN RUDOLF (my grandfather) and HYPPOLITE ROBERT, both traders in Izmir. The two brothers must have agreed to court the two daughters of the English doctor WILLIAM PIERRE CHASSEAUD, ANNE MARIE (my grandmother) and SYLVIE. Two half-sisters separated by widowhood.

Of all these people, I only knew my grandmother ANNE. My paternal grandfather had died, and his brother had left in the 1920s with his family for Egypt where the trade was practiced in less turbulent conditions than in the young Turkish republic of MUSTAFA KEMAL

My “Granny Anna” gave me a lot of love during our short stays in Bornova, a village near Izmir where the western Smyrniot Diaspora resided - and I hope to have returned it enough, in the expeditious way of children. In the middle of her small living room was the “tandoor” surrounded by four chairs. The mild climate of Izmir made it possible to spend the winter without heating. The tandoor was a table under which was placed a brazier which was lit when the weather was too cold. The downy table-cloth hung to the ground and could be pulled up over the legs to warm up. Greek friends sometimes came to play “bezique” around this table and counted the points on curious wooden tablets (called Goodall’s counters by historians) the keys of which were lifted. I spent evenings drawing and leafing through illustrated magazines while listening with one ear to the incomprehensible arithmetic operations of the game in progress, spoken in Greek, before I was sent to bed. The focal point of the furniture was a “rocking chair” mounted on a wooden base and equipped with springs. I spent hours trying to destroy it. Prominent on the wall was a document that commemorated the Swiss 1291 pact and two 18th century drawings of ancestors

In the garden grew a large fig tree which always bore tasty fruit. A Greek neighbour made delectable “kulurakias”, ring-shaped butter cookies covered in sesame and “kourabiedes” sprinkled with fine sugar. I admit that these three highlights figured prominently in my thoughts during the “more or less long” trip that took us from Trebizond to Izmir.

The two cities are separated by almost 2000 km, and were accessible at the time by sea to Istanbul and then by train. There was no road yet along the wild and steep coast of the eastern Black Sea. You could also come from the interior of the country by crossing the passes of the “Transit Yolu” (transit road, in Turkish) that my father was building up to Erzurum, and then by train to Ankara and Izmir (Smyrna). The trip lasted between one and three weeks depending on the snow conditions of the passes or the state of the sea. The ports of the Black Sea were not yet sheltered by harbours and in rough seas the boats anchored offshore and waited for everything to calm down enough to tranship cargo and passengers. I have very bad memories of a week of seasickness in view of the mainland of the city of Samsun!

So I rarely saw my “favourite” grandmother. She was small, but made up for her size with her temperament. She noted with wonder and enthusiasm my “progress” on each of our spaced visits and showered me with praise. I thought she was definitely overdoing it and kidding herself about me - but I let it go. She still spoke to my father as one addresses a child - and I found it very strange that this man, so impeccable and omnipotent in my still naive eyes, should be treated in this way. She was fiercely Protestant and defended her place among the Orthodox, Catholics and Muslims around her. The Anglicans, however, were acceptable. Her surname CHASSEAUD was from a French Huguenot family which settled in England when the Edict of Nantes was revoked. It was enough to mention Louis XIV to make her explode in violent anger - as if this accursed king had personally hunted her down and banished her from his lands.

The elderly lady seated is my grandmother “Anna” - Anne Marie née Chasseaud. My father is standing behind her to the right. I don’t know any of the other people. As it was in Rize (as written on the back of the photo by my grandmother - postcard view) which is located far from Izmir at the east of the Black Sea, I doubt that it could be close members of our family. The writing on the back also indicated the time as Christmas 1928 (hence the fancy paper hats) is about the time my father undertook the construction of the new Transit Road and could explain why he was there.

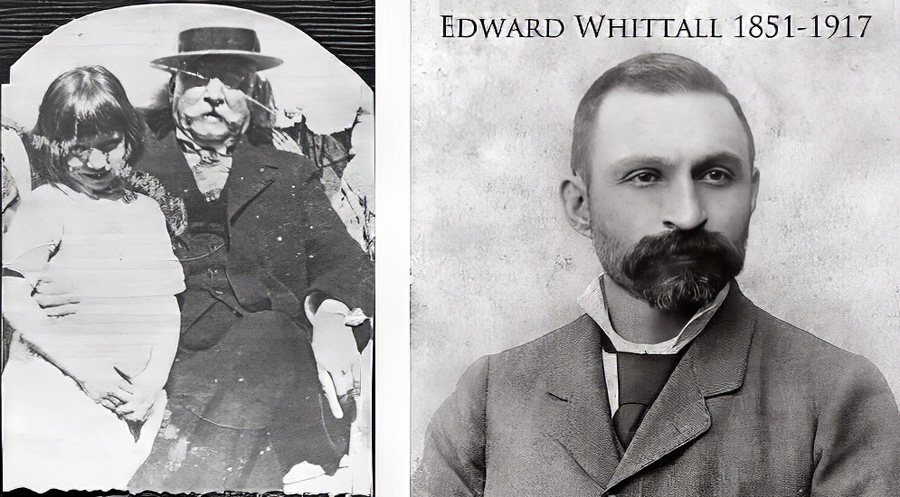

When we were in Bornova we stayed with my maternal grandparents, ÉMILE RAYMOND AIMÉ CAMILLE MARIE (..!) TISSOT (1882-1954) and RACHEL née WHITTALL (1881-1955). My greatgrandfather, AIMÉ JOSEPH TISSOT (1850-1935), had been director of the Izmir tramway company. RACHEL’s father, EDWARD WHITTALL, a recognized botanist, exporter of figs and currants at Izmir, owned a magnificent property in Bornova with a botanical garden. You entered the big house like a church with an organ at the end of the hall. On the right side of the hall, an exhibition room contained botanical collections, shells, stuffed animals and archaeological remains. I particularly remember the collection of multicoloured eggs shown to me by my great aunt RUTH GIRAUD, daughter of EDWARD WHITTALL, and whose husband EDMUND had bought the property during the inheritance.

Two of my great-grandparents, AIMÉ JOSEPH TISSOT (1850-1935) and EDWARD WHITTALL

My grandparents had a house big enough to accommodate us all, and located a stone’s throw from my other grandmother. A pretty vegetable garden with aromatic herbs bordered a pleasant corner in the shade of the olive tree adjacent to the well. In the centre of the garden a hatch gave access to a dark and threatening cellar which was called “bomb shelter” (English was the usual family language). Turkey had remained neutral in the global conflict - but the war remained very much in the minds of English and French residents.

We reached the house by an alley that ended in a dead end (at No. 3 “Aralık sokak” in Bornova). It was an ideal place to herd and confine the camels on market days, and there was always a camel driver or two on hand to ease our way home through the herd of unpredictable and skittish beasts, when it was needed. After they left, my grandmother collected the droppings - balls the size of a large walnut - for compost in the garden. They had the size and appearance of the succulent meatballs that my grandmother occasionally served, and she made me believe for a long time that it was indeed pan-fried camel droppings that we were eating!...

Even today, one of my favourite recipes is “Izmir style camel droppings”.

My “Granny Ray” was an excellent cook, but had a harsh and vindictive nature. Her three daughters HELENE, DENISE (my mother) and MARGOT suffered from it during their childhood. Young, she had distinguished herself with her sister RUTH (1884- ) by playing football – an unusual activity for young girls from good families in the 19th century – and they were said to be feared on the pitch!

I was often in conflict with her and owed my salvation to my mother’s intervention when the situation escalated. I was insulted for the slightest stupidity, and one day she called me a “bloody fool” on I don’t know what occasion. Not knowing that swear word, I found this image of a “blood-dripping fool” quite original, and I brought the formula out to her the next time around - and it was my mother who saved me from the beating!

The most memorable incident was that of the needles. My grandmother “RAY” had her assigned armchair in a corner of the living room. One of those large, softly padded, deep Victorian English chairs into which she sank heavily when she was tired. Following I don’t know what annoyance, I took my revenge one day by sticking a few sewing needles pointing up in the chair. I still distinctly remember the eruptive way in which she got up with a cry perceptible throughout the neighbourhood. And it is once again thanks to my mother that I still have to be in this world!

She had her revenge a little later, when we went to Izmir to operate on my tonsils. The operation rendered me mute for two days, and she came to my room to make fun of me copiously without my being able to reply to her. But I finally ended up having the last word – by surviving her….

My relationship with my grandfather, “Papa Émile”, was very different. He had been an officer in the French intelligence services and had spent several years in the countries of the Persian Gulf and in India. I spent a lot of time listening to him recount his adventures. My favourite stories were those related to his ordinance DJEGESHA when he was based in Baghdad. He was sort of a “Ran-TanPlan”, if we refer to a well-known French comic strip, and who did everything with energy and dedication but always arrived at a result other than desired. He persisted, for example, in doing the laundry “the old fashioned way” by beating the laundry hard against rocks. So my grandfather had to buy a new uniform after every few washes.

The intelligence services also brought him to the Balkan countries. Albania was already a sensitive area where diplomacy was bogged down. Accompanied by his local agent, one day, the latter showed him a house and said “Do you see this house? This is where the family that has been enemies of mine for generations lives - and the worst insult they can do would be to shoot you, my friend, right now in front of me! - But don’t worry! If that were to be the case, I will go and shoot all the members of this family myself!”.

It was in Izmir that my grandfather met RACHEL WHITTALL, from a family of English merchants and bankers established in this colony - which was not one - within the Ottoman Empire which was also coming to the end of its role in world history. My mother and my two aunts were born there, and spent their childhood between Izmir and Marseille where their father was attached. I don’t know much about their Marseille period, except for the fact that my grandfather had been assigned by the French army a horse that had served at the head of a tram team on the left side, and who, once freed, trotted sideways pulling to the left - and couldn’t bear another horse in front of him.

Papa Émile was already old when I was born. He suffered from a cataract which obscured his sight and forced him to move around with a cane. The surgical operation was still dangerous at the time, without antibiotics, and in Turkey. When we were in Bornova he took advantage of hiring me as a guide and we took long walks in the surrounding countryside “to pick mushrooms”. We even found one on one occasion - which my grandfather declared inedible after hearing my description. These cryptogams no doubt served as a pretext for him to distance himself from boredom at home and to tell me adventure stories, real or imaginary, to which I listened with gratifying attention.

My mother’s older sister, my aunt HELENE would have seen me a few months old when we were in Izmir in 1942. But I don’t remember. She left shortly after for Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe today) to Salisbury (Harare today) with her English husband RALPH THEUMA (son of POLYCARP THEUMA and MARY VITALE), where they had three sons CEDRIC, DENYS and KENNETH. Unfortunately, I never met my “African” first cousins, but my aunt wrote to me and sent me books several times when I was in Lausanne in 1951 - 1953. She even invited me once for the holidays, but my parents did not accept, and I still regret it.

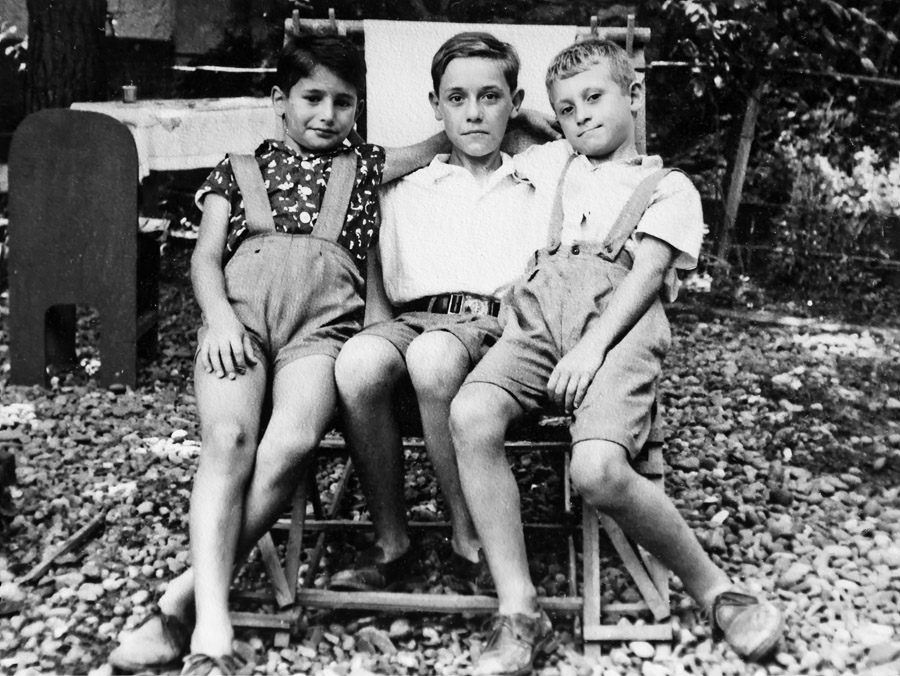

My other aunt, MARGOT, the youngest of the trio married the Englishman ELDON GIRAUD (my future godfather) and they had a daughter DENISE. My aunt MARGOT died before I knew her of heart disease. On the other hand, I often played with my first cousin when we were in Bornova. She was a year older than me, and always one step ahead of me in games. ELDON had remarried with JANINE (who became my godmother). She had a Greek father and a French mother and I liked her despite the fact that I didn’t understand either French or Greek at the time... Her father had been the architect of the last Sultan. Their family eventually settled in Istanbul.

In March 1940. From left to right: ELDON GIRAUD, aunt MARGOT, grandmother RACHEL, grandfather ÉMILE, my mother, grandmother ANNE.

My “African” family in Salisbury. From left to right Aunt HELENE, CEDRIC, KENNETH, Uncle RALPH, DENYS and his wife MARGARET.

My father explained to me that “godfather” and “godmother” were people who would roast in hell for my sins as long as I was not confirmed responsible by the church. I tried to imagine ELDON, in costume, with his tie, with his slicked back hairstyle and his serious expression, and JANINE with her intellectual bearing and her perfect appearance, sprawled on a brazier and bothered by imps equipped with three-pointed pitchforks, and I thought that the church must be making fun of us with that stuff.

They had, anchored on the Bosphorus, a raft reachable by motorboat which served as a platform for swimming. The current was quite strong, and I remember swimming back to the raft was sometimes worrying. My cousin Denise was doing better than me - leading the game as usual. Once, after a swim, she lured me into the bathhouse to initiate me into the game of anatomical comparison. But I was far too young to appreciate it at its fair value…

With my grandmother ANNE, my mother, my cousin DENISE. Approx. 1944.

DENISE was very beautiful when I saw her for the last time in 1958. I was 17 years old, I was on vacation in Turkey and was preparing to take the federal maturity exams that would allow me to enter University at the next session. She had married CHARLES WILKINSON, the son of the English consul in Izmir, and was carrying her baby ALAN, a few weeks old, in her arms. A few years later, my father wrote to me that my cousin had divorced and remarried EDWIN CROKER, vice president of administration at Robert College in Istanbul. I didn’t hear from her again until 2011, when my step-daughter BARBARA STRYJENSKI found her using Facebook! When Robert College was “nationalized” by Turkey, they moved to Beirut, and then moved on to Mills College in California before finally settling in Alexandria, VA, USA. ED joined the American Association of Medical Colleges in Washington, D.C. until his retirement. They have a daughter, FIONA, who has a son MICHAEL.

“Tea time” at Londra Oteli in Istanbul with DENISE. “... the photo of the Two of us sipping tea looked like an elder couple on a date!” – to quote DENISE in 2011…

Trabzon - Ortahisar (1941 - 1945)

By brushing the gray sand of the beach near the port under construction of Trebizond with a powerful magnet that my father had recovered from an electric meter, a “beard” of tiny particles of iron oxide - magnetite - formed little by little. I had collected enough to fill a thimble. I did not yet guess the close link that this black dust had with the Cosmos - the astrophysicists of the time did not understand it much better – nor did they know of its essential role in the appearance of life.

Poured onto a sheet of paper, this fine “cosmic dust” of delicate appearance formed mobile, harmonious and subtle designs when the magnet was moved under its support. A light breath was then enough to disperse all traces of it, and the dust fell gently to the ground. Billions of years old, however, this substance harboured a sinister past - guilty of the cataclysmic annihilation of countless stars - stars that had succeeded at their expense in making iron.

With my little enamelled iron bucket bearing the design of a duck, I learned to mould towers and ramparts with wet sand. My father directed from 1946 onward the construction works of the port of Trebizond. The company’s offices had been placed near the beach, which was to be sheltered from the waves once the 850 m long main jetty of the harbour basin had been built. Engineers used to take their families to the beach on their way to work when conditions were good, provide them with a picnic lunch, and then drive everyone home at the end of the day. I had plenty of time to get to know the sand in the years that followed. I’m not frustrated if we have to give up going on a beach vacation.

It is said that I was born on November 10, 1941 at the house we occupied in the Ortahisar district of Trebizond. It was around four o’clock in the morning - as if premeditated in order to further inconvenience my mother who had had to put up with me for many months - and make Dr. OSMAN ÜGÜREL who came to assist her lose half the night. The latter was our family doctor, and became a good friend of my parents. I last met him in 1966 in Istanbul where he ran a clinic. He was very nice to me; except when he was giving injections! His large steel syringe had a graduated glass cylinder, cracked and slightly yellowed by use, and which he put to boil in water in its stainless steel box on a small alcohol burner in order to sterilize it. Watching the preparations was more distressing than the injection itself.

One night (in 1945 or 46), I woke up to see my parents in the last stages of panic and Dr. OSMAN, worried, was holding his syringe fitted this time with a needle of formidable length. When I started saying I was fine and didn’t want one of those damn pricks - especially not with that needle! - I was told that my parents hadn’t been able to wake me up, that my pulse had disappeared, and that Dr. OSMAN had just given me an injection in the heart! I never knew what happened, but this time I escaped the torture of the preparations...

With Dr OSMAN in 1966 in Istanbul

We left the house in Ortahisar to live in a house in Taksim Sokak (street leading to Boztepe - the hill overlooking the town) in 1945. That was before August. The news of the bombing of Hiroshima came when we were living in our new house. This makes it easier for me to locate my oldest memories in time.

Which was the oldest of all? My birth surely, and I don’t remember!

Waking up in the dawn where I discovered at the foot of my bed a pale white balloon shimmering with mauve (coloured ones probably didn’t exist in wartime) and a few treats. My birthday, but which one?

Or: - the basket in which my mother had transported me to visit an acquaintance had been placed next to the cradle of another baby. This “being” was instinctively antipathetic and repulsive to me - I still feel this aversion without being able to explain it.

On the table, and within easy reach was a key. In my eyes at the time, and I distinctly keep the image of it, this “weapon” was indeed the length of a hussar captain’s sabre and had the thickness of a baseball bat. I grabbed it and hit “it” on its head. This is the memory associated with the first scolding received from my mother!

Or also: - The sleigh pulled by two horses advanced at a good pace at night in the snow - doubtless crossing one of the Erzurum road passes that my father was building. A lantern lit up the horses’ rumps and marked the fall of large snowflakes that landed on the rapidly passing path. Suddenly, one of the horses noisily dropped its load of smoking manure. A surprising image still etched in my memory.

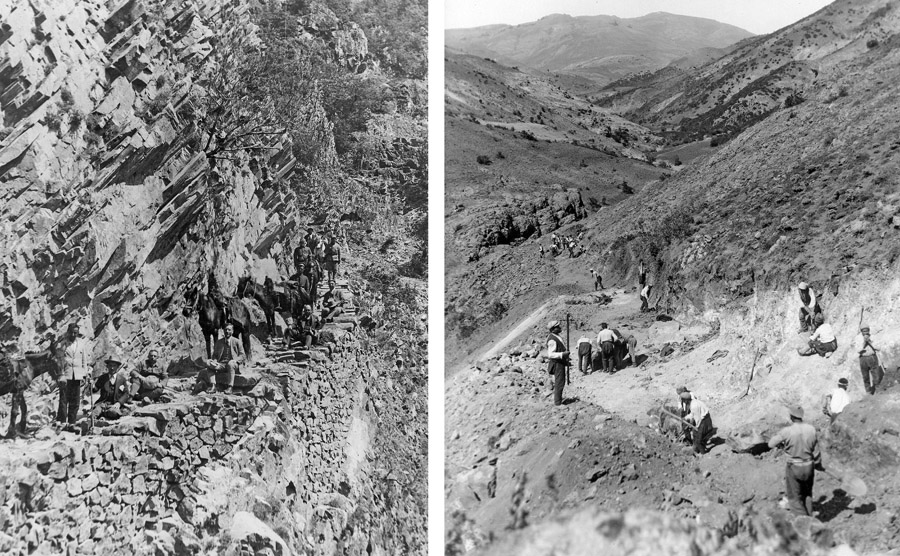

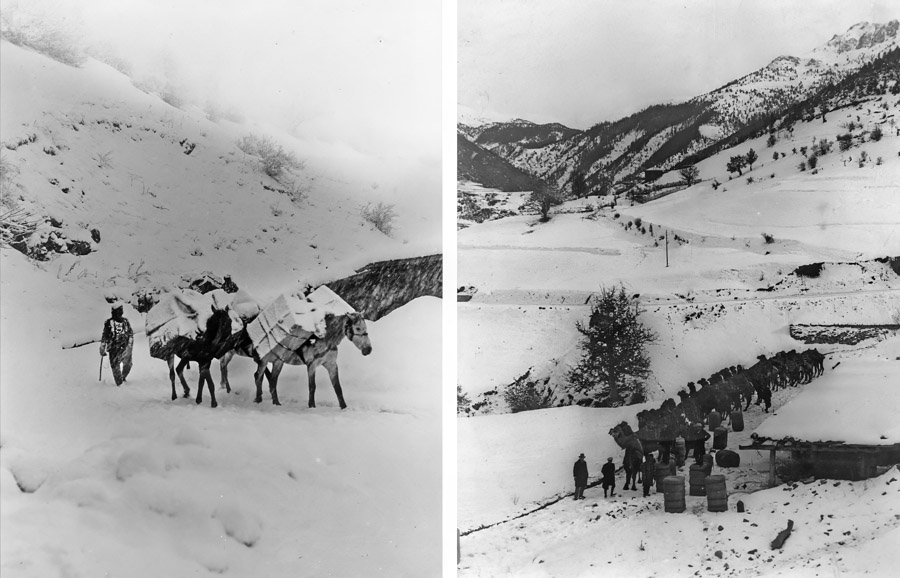

When the car could not pass, on the road to the Kop pass, on the way between Trabzon and Erzeroum. Abour 1940.

We were in Erzurum, and my parents were waiting on a railway quay. From a distance, then gradually and quickly becoming unbearable, this huge machine issued from a nightmare arrived whistling, creaking, panting and spitting steam everywhere! I fled from the din and my mother had to run to catch up with me on the station platform. We were going to Izmir by train, for the first time for me by going through the interior of the country.

There were also the planes which flew sporadically over the city. Some German bombers which had accomplished their mission in Russia preferred to return via Turkey, neutral in the conflict and whose air force and flak were much less of a deterrent. It was a bit of worry and apprehension when a plane was passing. We had received gas masks, in case a bomber got the wrong target. I once overheard my parents whispering to each other that it was a good idea in principle, but that these masks would not fit a child’s face. My mom put it on once to try it on - and it was terrifying to see! One day we drove to examine the wreckage of a German fighter bomber that had made a makeshift night landing on a nearby beach after being damaged by Russian flak. Not much remained except for its charred metal carcass with twisted propellers. I don’t know if the crew survived.

Our house overlooked a dirt road, furrowed with marks made by the wheels of carts and punctuated with the dung of horses and other passing cattle. The rain and the contents of the buckets of waste water poured by the neighbours formed brownish coloured puddles with iridescent reflections. I had a good friend in the house next door and together we played all sorts of more or less respectable games. One day, after watching his mother make rose water - an essential ingredient in Turkish lokoums - we decided to copy the recipe. We picked rose petals, crushed them in a matchbox, filled the box with water from one of the puddles on the road, stirred and drank the contents.

The taste was not up to our expectation. We added sugar in the next batch, but it still wasn’t great. His mother did much better.

The next day - we were both sick to death! Our respective parents, very worried, conferred. And it was finally Dr. OSMAN who got us back on our feet after a few days with the help of his pills - and his injections!

The Christmas tree had been placed next to the piano in the living room. I had received gifts, and among these was a sheet metal airplane which had the particularity of carrying lead bombs that could be dropped (we were in the middle of a war…). My parents having gone away for a while with neighbours, I was playing under the tree with my bomber when one of the bombs I had put in my mouth went down my throat.

The living room of the Ortahisar house seen from the dining room. The piano in the corner is my mother’s instrument. She was a rather good pianist - better than the pianist teaching at the Trabzon conservatory...

When they come back I tell them “I swallowed a bomb!”. The most funny was their terrified and simultaneous reaction “A Bomb??!!!” - as if it were a grenade that was going to explode any moment!

And Dr. OSMAN, called once again in the middle of the night, put me on a diet of bread soaked in milk until the end of the transit of the intestinal “bomb”.

My parents had invited friends for the evening. They had brought with them their daughter who was my age. Their conversation did not interest us much, so we were sent to play elsewhere. There was a room behind the kitchen that was used as a storage space and where some of my toys were also placed. On the way, I took a box of matches to show my girlfriend how well I knew how to make a fire. An old, empty tin can and a large bag of rubber bands were found in my father’s office stock. Placed on the raw wooden floor and the rubber lit, the brazier blazed cheerfully, giving off a wonderfully revolting smell with thick black smoke - and we were having a great time. Not very long unfortunately because our parents came running in a state of great excitement and put an end to this early physical chemistry experiment!

It was also in Ortahisar that I learned to count. Numbers were simpler than letters. For starters, there were fewer. And, then, the play that we could make with them was simpler and without subtleties. Numbers were easier to understand. They were not “abstract”, like certain words with a veiled meaning which only take on meaning when one has “experienced” them. (I still have a problem with abstract words…).

My mother taught me very early to do multiplication mentally. Multiplying by two was simple. By four it was twice twice, and so on. By three, a little more annoying, but we managed twice, plus once. By nine? That ! It was annoying! My mother showed me how to do it. To me at the time, a real revelation. Multiplying by ten is trivial. We put a zero at the end! Calculating by adding a “nothing” seemed less strange to me then than now, with my greater experience of “reality”… To multiply by nine, we multiply by ten and subtract once. I was sitting on my mother’s lap, in front of the living room window, and the light was coming from the right - when I realized!

I still use this method to multiply by nine. To multiply by seven?… That’s another story!

Seen from the living room, the dining room which had only one window on the right was quite dark and austere. I remember having loved pan-fried “hamsis” - anchovies - at the end of autumn in this room. These fish migrated in incredibly dense shoals in the Black Sea at that season, and the miraculous fishing was done with a net, and I even saw men taking off their shirts, tying up their sleeves, and scooping up anchovies with the improvised net. While swimming, we felt like we were in a living soup that tickled everywhere.

My parents were very surprised at how glad I was to eat these strong-tasting fish, arranged radially in the pan and fried without further preparation, because they were too small to be gutted and scaled - children usually hated it - and I asked to be re-served!

In this same dining room, one day, my father had invited the “Vali” - the prefect - of the prefecture of Trebizond for the evening meal. My mother had gone to great lengths to present the notable with a memorable meal. She had even prepared an English “Jelly” for dessert to introduce him to a Western specialty. Everything happened in a friendly way, and the host was entitled to the tasting of the dessert. With impeccable aplomb he congratulated my mother on the delicacy of the dish - until the moment when my parents tasted it in turn and discovered that my mother had confused the salt with the sugar...

The window of the room overlooked the neighbouring house separated by a narrow alley. In the summer, when the windows were mostly open, you could hear the neighbourhood activity. My mother sometimes commented on what she heard. And sometimes what she claimed to have perceived did not correspond at all with what I had heard. When I pointed this out to her, she said “they” were slandering her. I found it very odd - I hadn’t heard anything that corresponded and didn’t know what “they” it could be. I couldn’t know it, but it was the beginning of her illness that would later transform our lives.

In the house of Ortahisar I slept in a room which gave without door on the bedroom of my parents. The window was covered with a thick green and beige curtain decorated with irregular and intricate patterns that could let the imagination wander. At dawn, while waiting for my parents to wake up, I watched the fantastic landscapes come to life on the curtain, which gradually lit up with the onset of daylight. Animals and men constantly changed shape and moved through shifting mountains and living forests in unpredictable ways. Every morning I had my cinema session, and it was almost with regret that I heard my parents get up.

The first two or three years of existence are also those where one begins to test the limits of the permissible and to seek the “why” of things. My mother sometimes spoke to me of a strange thing which she called “GOD”, and which was to be feared because he had the power over everything. I had pictured him as an old bearded man with a stern look who hid his wickedness behind the clouds - and that was why we never saw him. One day I was sitting with my mother who was sewing in front of the living room window which overlooked a vacant lot and the river, a little further.

Beautiful cumulus clouds were building over the nearby hill towards the setting sun. The idea suddenly took me to shout to my mother “Look Mom! - over the clouds! - there is GOD who has come out and I see him!”. My mother told me to stop talking nonsense, and that if GOD got angry he would punish me. And at that moment I saw descending from the sky a kind of comet preceded by a brilliant five-pointed star - as the star of the Magi is depicted on Christmas greeting cards - and which exploded blindingly above the wasteland. I had the scares of my life, and my tears were all the more frustrated because my mother who was trying to console me hadn’t seen anything...

On another occasion, we were coming out of an invitation and waiting for the taxi on the sidewalk. I had a score to settle with this GOD who dared not show himself and frightened little children. I don’t know what challenge I threw at him, but immediately afterwards a dazzling flash - zigzagging like the warning symbols on electrical panels - sank into the ground at my feet. I had lost some of my naivety and said nothing, and my parents didn’t see anything...

It was my last dialogue with Him. Years later, seeing around me people who “believed” and who thus seemed to go through life’s frustrations and bitterness with much more serenity than I did, I diligently sought enlightenment. But I met only night and silence. On the other hand, I think I better understand the vagaries of perception in a person who contemplates the play of light for a long time in the darkness of a cave - or in someone who withdraws into the desert and the intense silence that reigns there makes his own thoughts deafening.

We are at peace when the darkness remains black and the desert keeps its silence.

Intermezzo 1 - Trees

My parents were both born in Izmir. My father in 1896 and my mother in 1909. I know very little about their childhood. When I was sent to Switzerland in 1951 to finally begin my formal schooling, I was too young to be interested in these aspects of family life.

My mother and her two sisters spent their childhood and early adolescence between Izmir and Marseille. Their family then settled in Izmir where my grandfather ÉMILE TISSOT opened a small soldering lamp business after being retired by the French army.

On my father’s side, my grandfather had become deputy director of the Ottoman Tobacco Board. He died in 1919 following a riding accident. My father had in the meantime been sent to England for his secondary studies and then to the Department of Civil Engineering at the University of London - City and Guilds (now Imperial College of Science and Technology).

My parents were married on October 5, 1935 in Istanbul.

Everything seemed very simple to me until 1977. But you had to reckon with family secrets - or rather of unspoken family stories!

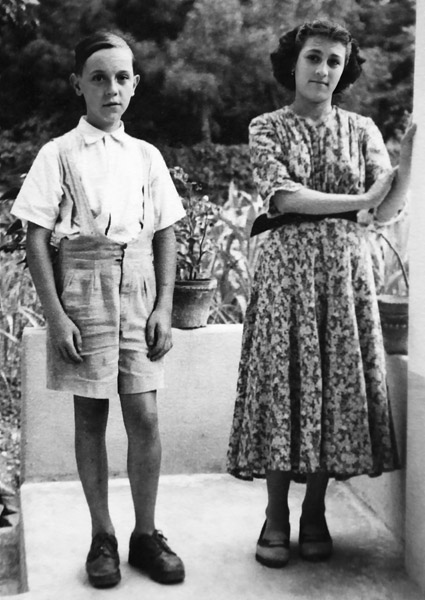

My father WILLIAM RUDOLF CRAMER at about 13 years old (around 1909) in England.

My parents in 1938, presumably taken close to Izmir.

My father had a “Levantine cousin” in Küsnacht near Zürich whom we often visited. In the Levantine community everyone was considered to be “cousin” of someone or other…

LORNA VAN HEEMSTRA was from a Dutch family established in Izmir (her own cousin AUDREY, daughter of ELLA VAN HEEMSTRA adopted the name of HEPBURN from which her father’s family descended and distinguished herself as an actress). LORNA had married the Zurich banker MARIO HODLER.

After the death of my father (in 1975) and my return from a first stay of two years in Chile at the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in the Southern Hemisphere, LORNA told me during a visit “I don’t know if I should tell you - but…”

In fact, I learned that my mother had already been married to a certain FRIEDRICH DE CRAMER, an English citizen despite his first name - without any connection with my family despite his surname - and divorced him on May 2, 1935 in Vienna. The couple had a reputation for leading a turbulent and eccentric life in Izmir and elsewhere in Europe, and everyone was very surprised to see my mother fall under the spell of a serious and modest man who lived in the austere and wild provinces of Eastern Anatolia.

Knowing my mother and her unpredictable sense of humour, I think she must have found it very amusing to go on an adventure while keeping her alliance name but throwing the particle away!

For me, it was good to hear this news. And it took me another ten years to discover the other two secrets.

In 1986, I had written to ROBERT CRAMER - a cousin from a parallel branch of the family who was a biochemist at the Institut Pasteur in Paris - and who spent his free time reconstructing the family genealogy until the middle of the 14th century in Zürich. I had spotted three “ROBERT CRAMER” in the Geneva telephone directory, and asked him if these people had anything to do with me.

Unquestionably, the family tree bore many fruits named ROBERT!

They were indeed all of my close family… My great-uncle and first cousin of my father ROBERT WILLIAM (born in Izmir), his son and my cousin ROBERT FRANÇOIS (born in Alexandria) and his first son ROBERT (born in Amsterdam) who had already started a political career with “The Greens” in Geneva…. And nobody told me about it until 1986!

And - the letter from “ROBERT in Paris” ended with “P.S. your father had a half-brother CHRISTOPH CRAMER who lived in Chile where you are working….” - The fresh icing on a very old cake!

I learned that my grandfather had been married for the first time to MARIA TYPALDO, daughter of a Greek lawyer at Izmir! They had a son CHRISTOPH in 1890, but his mother died in 1894. It was in 1895 that my grandfather married ANNE MARIE CHASSEAUD, and my father was born the following year. My dad must have frequented his half-brother who was six years older than him - and he never told me about it!

CHRISTOPH married in 1961 RAQUEL MALVINA PEREZ (born in 1896) in Santiago de Chile. They had no children given their ages. I did some research during my various visits to Chile, but did not manage to get more information.

Once again, it was good to know how things actually turned out to be!

In genealogy, the trees hide dead and broken branches beneath their luminous and glossy foliage.

Intermezzo 2- Brigandage

[The hot wind blowing from the North East had died away with the fall of evening. The musical tinkle of the ore laden buckets travelling along the aerial ropeway cable, followed by the clatter of their entry into the terminal station and the rumble of the ore discharging through the chutes had been stilled. Men and women workers drawing water from the single deep well for their ablutions before the evening prayer had retired to their quarters to cook the evening meal. Over the village, brooding in the sweltering heat of approaching night, a great stillness prevailed, now broken by the chirping and whirring of countless insects.

I had just lighted the oil lamp in the little office giving on to the garden when the door opened and a short, stockily built man in his thirties, clothed in the grey and black gaiters, short trunks and waistcoat peculiar to the peasant of the locality, walked into the room. After the prescribed greeting of Aksham Sherifler Hayır Olsun (may the sacredness of the evening be beneficial to you) had been exchanged and the ceremonial cup of coffee had been drunk to the accompaniment of an exchange of news on such banalities as the state of the crops and the weather, the visitor straightened up and said: “I bring you the compliments of Kutchuk Huseyin”.

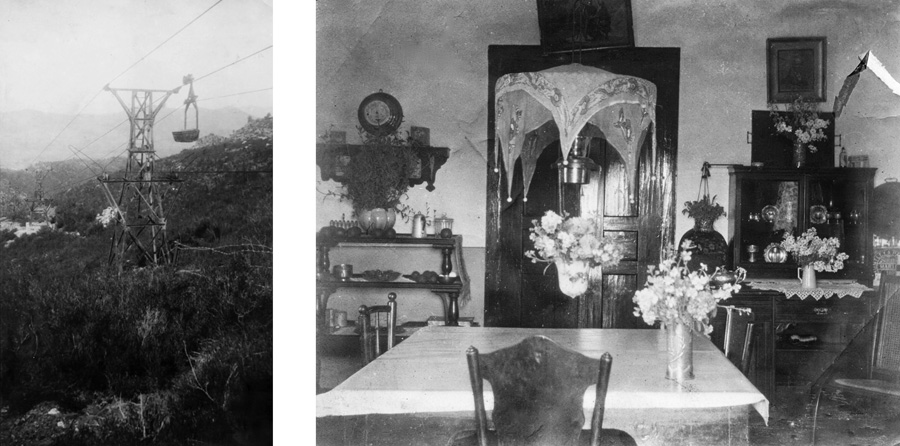

Dip Sahrinj in 1926.

Some years after the first world war, having graduated in Civil Engineering in London, I had accepted an offer of employment by a firm holding concessions for the extraction and transport of emery ore in South Western Turkey in Asia. An aerial ropeway, 12 kilometres in length and linking the nearest mineral deposits to the terminal station at the little village of Dip Sahrinj, near the small town of Milas, already existed. Small residential and office buildings together with stores, stables and outhouses were located at this point and since payments to personnel and workers were effected here, moderately large sums of money were usually available. It was my first job and I had gone to some pains to study the Turkish language.

The end of the decade preceding the year 1930 found the country not yet settled down completely after the bitter struggle of the War of Independence. Widely spaced villages served by narrow and precipitous tracks, arid limestone peaks, rugged gorges and dense pine forests where the wolf, the panther and the wild boar still roamed unmolested presented opportunities for the practice of outlawry and brigandage.

The aerial ropeway / The dining room at Dip Sahrinj in 1926.

Warned, shortly after my arrival, that a brigand band, captained by one Kutchuk Huseyin (little Huseyin) by name, was operating in the neighbourhood I had decided to engage two night watchmen whose services in the event of a raid would be limited to giving timely warning. It was with a feeling of apprehension therefore that I heard my visitor say: “I bring you the compliments of Kutchuk Huseyin”. “Return my compliments and convey my thanks to Kutchuk Huseyin, what are his wishes?” I asked. “Kutchuk Huseyin has heard that you have engaged two night watchmen and that you have done this thing for fear that he might molest you. Does he not often see you riding alone on horse back along the lonely forest paths and could he not capture you and hold you to ransome if his intentions were evil? But he hears nothing but good of your Company, how that the workers are well and regularly paid, are provided with comfortable lodgings and are treated with justice and kindness. He has sent me to ask you to dismiss the night watchmen and to assure you that you and yours are under his protection and when this has been made known (here he leaned forward and his black eyes flashed) none will dare to trouble you.” He left as unobtrusively as he had come. Enquiries carried out later convinced me that my guest had been none other than Kutchuk Huseyin himself.

Many years have elapsed since occurred the incident related above and during this period of over thirty years, lived mostly in the less developed parts of the country, I have been a witness to countless examples of the kindness, the loyalty and the hospitality of its people. But, clear and unforgettable through the fog of the years, stands out in my memory this act of generosity of Kutchuk Huseyin, one of the last of the Turkish brigands with honour.]

This account of an event of “brigandage” experienced by my father towards the end of the 1920s, and which he wrote after I repeatedly urged him to do so, is unfortunately the only one he wrote. But the “agreement” with certain brigands had started much earlier in the family, with my paternal grandfather. Hostage-taking and ransoming of wealthy families, especially foreign ones, was actively practiced at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century in Turkey. My grandparents told me about more or less serious cases. That of the son of a family of English bankers in Izmir whose family was reluctant to pay the ransom, and the package that one day arrived at home and contained a first ear, with the promise that the second one would come soon if the ransom was not paid...

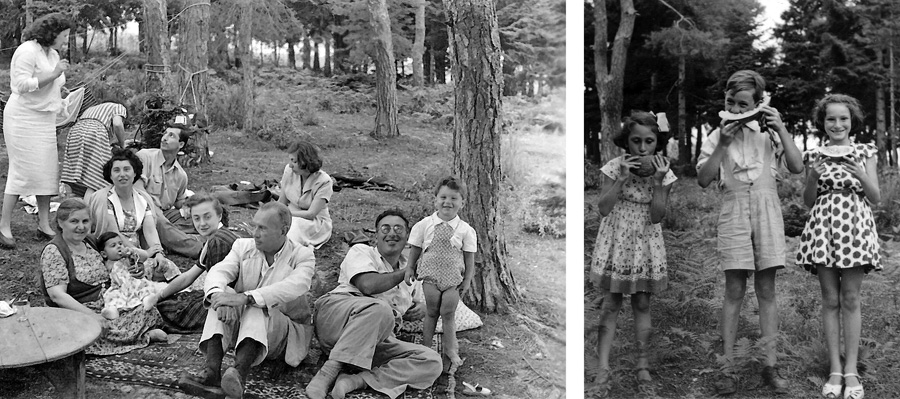

My grandparents liked to go with their family on weekends to spend a day in the countryside and have a picnic. But the conditions were also ideal for being ambushed while moving and being ransomed. For reasons unknown to me - perhaps related to his position in the Ottoman Tobacco Board - my grandfather had won the friendship of CHAKIJI MEHMET (Mehmet the knife-man), the leader of a band of notorious bandits of the region. Thus, before each excursion, a message was sent to him and he organized a discreet escort to ensure the safety of the family.

My father later used this strategy when he undertook the construction of the Transit Road (Trabzon - Erzurum) in the 1930s - 40s. As the construction progressed, he inquired about the main local gang leader and “sat down” with him to gain his trust and protection. At that time, the young Kemalist republic did not yet have adequate control of the east of the country where the often corrupt provincial authorities established during the decline of the sultanate felt their autonomy threatened. For some villages, the only way to get enough resources was to resort to banditry. Band leaders were often men in conflict with authority, who invested themselves in their village, and were highly esteemed and protected by the local population.

The Turkish public works department hired my father to make this old caravan track belonging to the “silk” network passable. XENOPHON, during his retreat from Mesopotamia during the winter of 401 BCE, followed this same trail, and it was in view of the Black Sea at Trebizond that the famous “θάλασσα! θάλασσα! / thalassa! thalassa! !” was uttered.

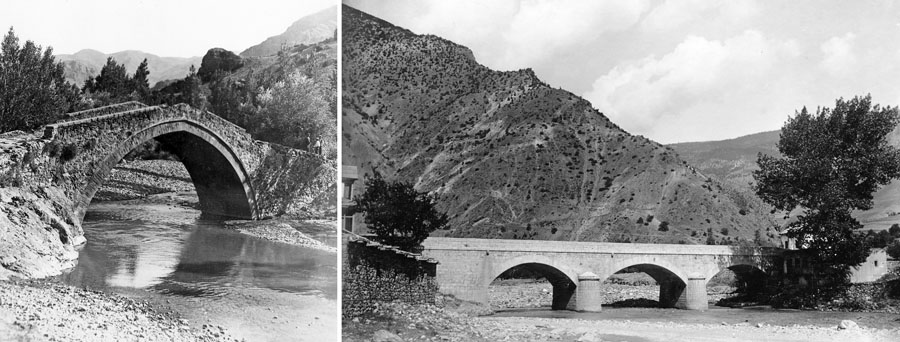

Villages near the projected road were sometimes hostile to the central government. But my father and his group of engineers managed to win their cooperation by employing local workers, paying them well and above all by ensuring that they were well treated. Small public utility works - repairing a village road, repairing a bridge in poor condition, stabilizing a river bank - not provided for in the specifications of the main project and carried out free of charge greatly helped to establish trust.

It was essential, however, to get on good terms with the most important man in the area - the local leader of the band of brigands!

My father told me several other stories in connection with the brigands. But he didn’t put them in writing.

At the beginning of the construction of the road, the trail was not even passable by motorcycle in some places and travel had to be done on horseback. On one occasion, my father had received a beautiful, immaculate white horse which was the admiration of the neighbouring villagers.

One day, a delegation from a village a few kilometres from the engineers’ camp came to find my father. A prominent family in the village married one of their daughters to the son of another prominent family in a neighbouring village. The event was useful for the good understanding between the two communities. According to tradition, the family had to arrive at the future son-inlaw’s house ceremonially with the dowry, to the sound of the “zurna” (a straight flute with a nasal tone) and the “davul” (a large monotonous and sonorous drum) and the bride mounted on a horse.

For the marriage to be successful, it was auspicious if the girl showed up on a white horse. Now, the only white horse of sufficient beauty in the country was my father’s! So the family begged him to lend them his mount for the occasion - and begged him to be their host and take part in the ceremony and festivities.

The festivities that followed weddings of this importance could last several days or even a week, and alcohol was consumed in abundance - “raki” (aniseed drink, similar to Greek ouzo) not being specifically prohibited by the Koran. An “ethnological experience” which did not please my father too much because he had other things to do, but he accepted the invitation to maintain the benevolence of the population vis-à-vis the company.

In the village, they took care to lodge him in the safest house in the place, and that was with the local brigand. A very courteous and helpful man who offered to put his bed on the balcony, because it was very hot at night. The party became very animated, and my father found himself obliged on several occasions, to respect customs and honour the newlyweds by discharging his revolver in the air in order to signify his enthusiasm during the revelry. When night came, his host suggested to him that it might be more prudent, given the circumstances, to retire inside the room during his sleep. After a few days of celebration, he thought the time was right to get his horse back and discreetly return to his work without hurting too many susceptibilities...

Banditry was still practiced in 1968, when I travelled to eastern Turkey to visit those regions of the country, Lake Van and Mount Ararat. The bus driver who took me to Tatvan told me that a week earlier a bus had been stopped and held to ransom by a band of bandits on the same route. After having stripped all the passengers of all their belongings, the brigands had given each person the sum of ten pounds, so that they could have enough to pay for a decent meal once they arrived at Tatvan. A simple gesture of humanity!

Mount Ararat and its two peaks: Great Ararat (5137m) and Small Ararat (3896m).

Transit Road - Some pictures

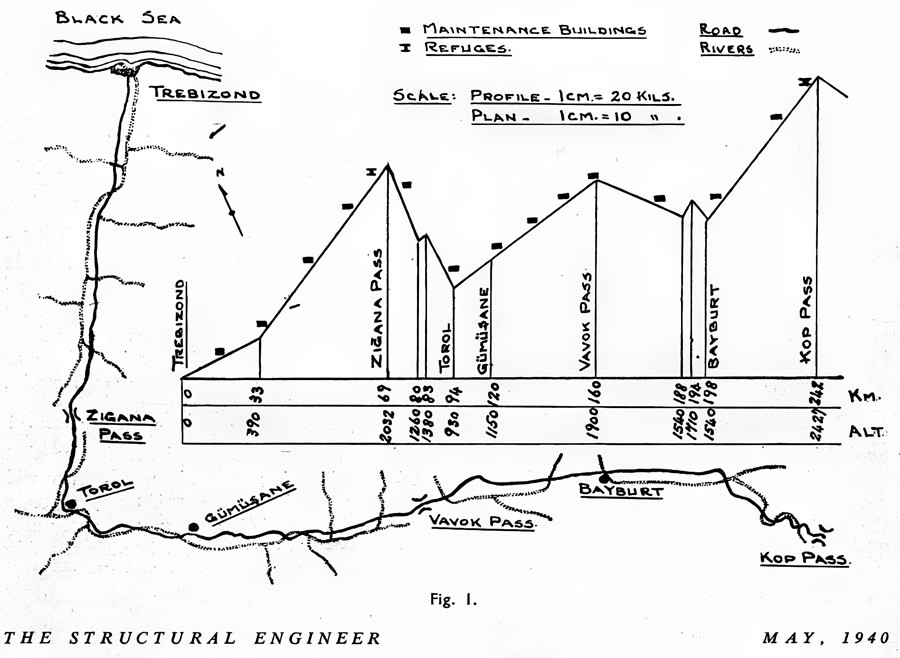

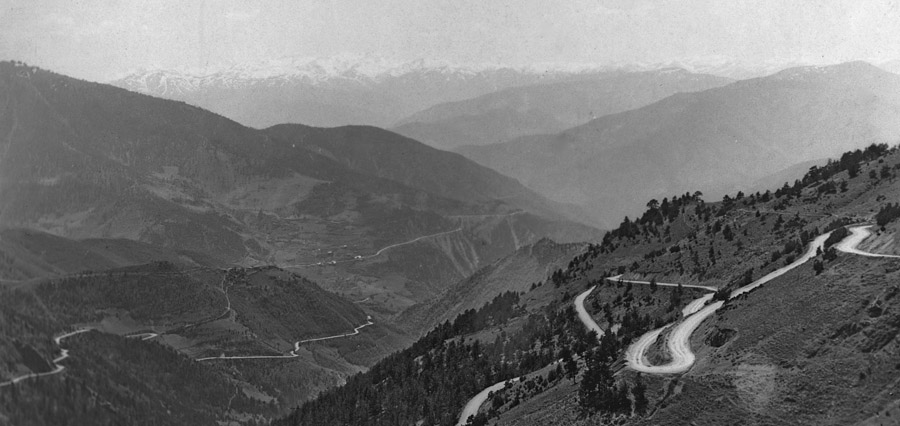

Profile and route of the first part of the Transit Road (Transit Yolu) taken from a publication by my father

View full account of the construction of the “Transit Yolu” my father published in 1940 in the “Structural Engineer”.

The path to be made passable by car / Preparation of the road

The engineers’ camp / The “office” (my father 2nd from the left) and the work team leaders.

Caravans

Caravan of the “arabas” (horse drawn carts)

Old road / New road

My mother, at the Kop Pass. / The Anatolian Sheepdog puppy “BALOU” given by a construction worker to my parents, had grown up well...

Ascent to Zigana Pass

Refuge near Zigana Pass, and its storm bell.

The transit road had been completed in 1940 - 41, and the work that still concerned my father was limited to the implementation of the maintenance of the section going to the Kop pass which culminates at 2427 m at 250 km from the sea. This unpaved mountain road was subject to harsh winter conditions. Its maintenance and the guarantee of passenger safety required the presence of teams of workers approximately every 10 km. In case of snowfall, all clearing was done by hand - with shovel and pickaxe - there were no machines at the time. Each team was responsible for a shelter that could accommodate travellers in difficulty. At higher altitude, these refuges were equipped with a bell that was rung during snowstorms to guide the traveller. Conditions were sometimes difficult - but the through traffic was kept that way throughout the winter.

My father was therefore often on the road to supervise the proper functioning of the system. My mother accompanied him most of the time. And, when I entered the scene, I was now part of the baggage.

Blurred visions of sleigh rides, of cold weather, of the windscreen wiper sweeping the rain off the windshield of the car, of staying in shelters where the small window lets a dim light into the dark room - waiting for the storm to calm down. Time which stands still - which does not pass. The gasoline lamp placed on the table and which must be pumped from time to time to supply vapour to its woven asbestos sleeve, and which gives just enough light to illuminate part of the room. These are my first memories as “accompanied baggage”... Dark memories - clouded perhaps by the “fog of years” - images that do not always feel good when brought out of the oldest recesses of memory. I can understand why some have chosen to practice “forgetting”.

But also of the car slowly descending from the snowy pass. The regular rattling of the chains mounted on the wheels. The sun dazzling a white landscape wrapped in a pure blue sky. It is very cold and I am wrapped in blankets. Each breath produces a puff of smoke - I’m blowing clouds! Water vapour condenses on the glass and marvellous ice crystals form and grow visibly - drawing a landscape that evolves in a chaotic but orderly way according to a subtle symmetry.

All is not gloomy in old memories. Budding recollections still lurk there.

We had arrived by train in Erzurum after an autumn visit to Izmir to see family. The company car had come from Trebizond to take us home. The Kop pass was crossed without incident, with a greying sky. On the way up to the Zigana pass, a short but violent snowstorm got us stuck in snowdrifts near the top of the pass. A night spent in the car - fortunately well provided with blankets and provisions. Hearing that “their” engineer and his family were being held up on the pass, about twenty villagers and a maintenance team arrived in the morning with their horses. While clearing what they could of the snow, the men carried the car with their bare hands over the few hundred meters of impassable road. The driver and my father had the right to get off and follow on foot, but no way would his wife and son do the same!

An example of the loyalty that men accustomed to being mistreated can have towards those who have respected them.

Trabzon - Boztepe (1945 - 1951)

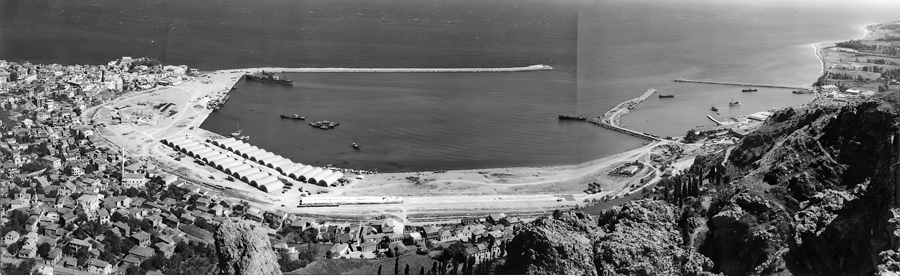

“The Turkish coast of the Black Sea provides, with the exception of Sinop, few, if any, natural harbours. Storms, if seldom of long duration, are sudden and violent.

The produce of the coast district, consisting chiefly of coal, tobacco, filberts, mineral ores, timber and potatoes, together with the ingoing and outgoing trade of the hinterland, gives rise to a considerable medium sized and small craft coastwise traffic.

It is not then surprising that when the government decided to adopt a harbour construction policy and drew up a building programme, two harbours, Trabzon and Ereğli, situated at the Eastern and Western end of the Black Sea respectably, should have been at the head of the list.

Trabzon (Trebizond) now has a population of over thirty thousand inhabitants. It is a town with a considerable historical background, having first received mention in 756 B.C., some years earlier than Rome. It is supposed to owe its name to the flat topped hill (now Boztepe) dominating it, likened to a table (Trapeza) and owed much of its prosperity to the fact that the Romans conducted their military campaigns against Persia from this port. Traces of the harbour built by the Roman empreor Hadrian are still extant as are the walls and fortifications of the later Genoese and local Byzantine occupants.

In comparatively recent times much of the town’s prosperity was due to the Persian transit trade and that of the Turkish provinces served by the Transit road whose terminus is Trabzon.”

This excerpt from my father’s report (read full report - summary of technical photos 1, 2, 3) on the acceptance of the construction works for the port of Trebizond, addressed to the Turkish public works department and to the two English and American development aid agencies, in 1957, situates the city in history.

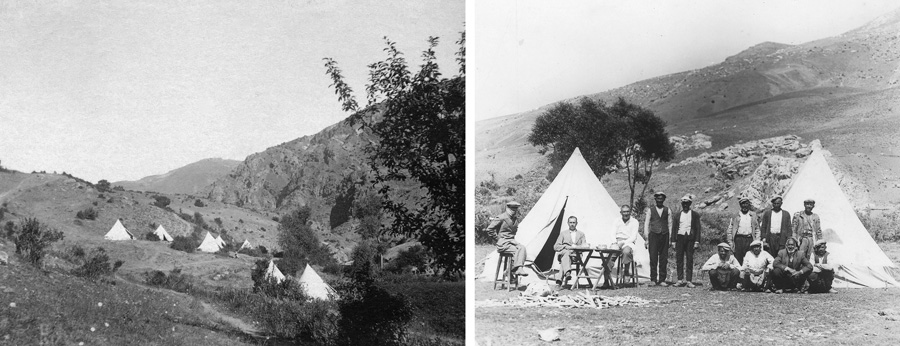

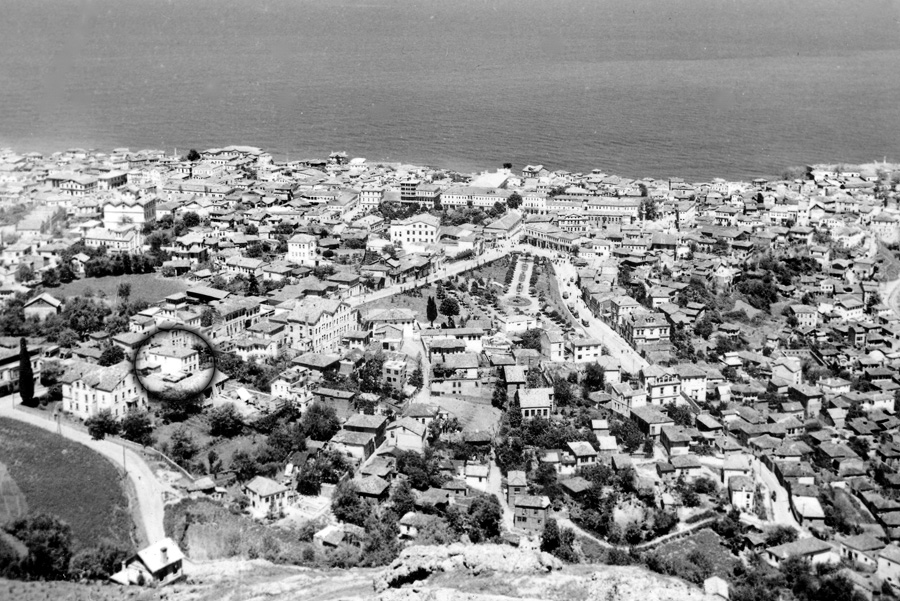

The construction of the port of Trabzon had been put out to tender by the Turkish government, and the project presented by my father and supported by three Turkish financiers from Istanbul had won. The company was now called “RAR”, after the names of the offices that financed the company. To be closer to the construction site in preparation, our family had moved to a house with a garden in Taksim Sokak, at the beginning of the year 1945. An old house in the local style with a pretty garden including two orange trees which were each bearing fruit every second year, a lemon tree, a “Japan-apple tree” with not very tasty fruits, an apple tree, an olive tree and a large vegetable patch where the main vegetables, and even corn, were grown. It was called the “Boztepe house”.

Remains of the port built by Emperor Hadrian west of the city of Trebizond.

The centrepiece of the garden was a date palm at the centre of a small rose garden, in front of the main entrance to the house. The tree must have felt a bit miserable in this climate of hot, humid summers and cold, snowy winters. Dates never grew larger than cherry pits, and were inedible. Fallen to the ground, they nevertheless germinated, and I had fun doing transplants – which were rarely successful.

A good friend of mine from that time (ARAS PERIKLI, who later became a mathematician and computer scientist at the Technical University of Trabzon) found me on the Internet in 2005, and sent me pictures of the neighbourhood. The house no longer exists. A building complex has invaded everything and the small public park below has been transformed. Everything has become unrecognizable. But the palm tree is still there! And the city presently has more than 300,000 inhabitants...

The neighbourhood around Taksim Sokak, with our house (surrounded by a circle) on the left. View from Boztepe (modern view) - the location of the former Cramer house indicated:

It was necessary to eliminate vermin from this old house of wood and plaster before moving in definitively. A thorough fumigation was organized with sulphur vapours and I don’t know what other harmful substances. Then we took the boat to Istanbul where my father was to meet his financiers to discuss the project, and let the fumes work for a few weeks.

Sea travel was not without perils towards the end of the war. Floating sea mines laid by the Germans and Russians still drifted offshore and were occasionally in the path of a ship. Russian warships, which had to negotiate transit through the Bosphorus with Turkey each time they passed, were not always very cooperative. We were once followed by a submarine of which we could only see the periscope - and without knowing what nationality it was, nor of its intentions. Then, at the entrance to the Bosphorus, the ships grouped together while waiting for the Turkish navy to move aside the anti-submarine nets to let them pass. And it is presumably on this occasion that the submarines took advantage of passing in their turn.

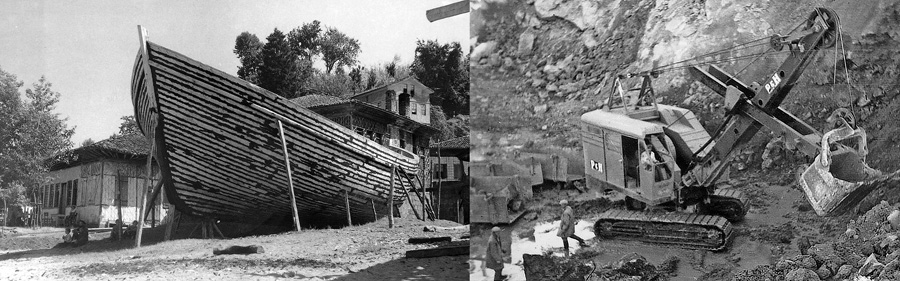

The main pier of the port of Trabzon was planned to protect an open natural bay at the eastern edge of the city. A rudimentary breakwater of a few tens of meters already existed a little further at the eastern end of the bay, and it was planned to make it a secondary port for the small boats and the navigation equipment necessary for the worksite. It was in very poor condition, and when the Russian occupation withdrew after the 1st World War, a few abandoned ships were laden with rocks and sunk close to it to serve as a breakwater. You could still see their carcasses emerging from the water like the bones of a dead fish. The construction of the jetty of the “small port” began immediately with workers gathering rocks from a nearby quarry wielding pickaxes, and using horse-drawn carts as well as a few trucks to bring them to the dike. Heavy construction machinery was not immediately available immediately after the war.

With my good friends SABRI SHAHMURAT (left) and ARAS PERIKLI (right) in 1954. SABRI was the son of the company’s technical draftsman and had a laconic, dry humor that I greatly appreciated. ARAS was the son of the driver - ŞEVKET PERIKLI - of the company. I frequented him and his brother NECMI a lot during my summer vacations in Trabzon. ŞEVKET EFFENDI was highly esteemed by my father

The “little port” in its primitive state / The first quarry, without construction machinery.

Despite the laborious reconstruction of countries emerging from the world conflict, England - and later the United States - continued their plans to help underdeveloped countries. England provided for the port of Trabzon railway equipment and cranes and made available the collaboration of a construction company, the Mitchell Engineering Group. The United States provided a bulldozer and a large self-propelled excavator. But this equipment was in Istanbul, and it was necessary to organize its transportation to Trabzon.

So was it that my father once again took us in the fall to Istanbul where my mother enjoyed browsing the stores for a fur coat while he negotiated to arrange transportation. The official shipping companies charged prohibitive sums to make the deliveries. He then turned to a flotilla of small private boats that made a much better offer. But, seeing the condition of the ships - where rust-perforated plates at the waterline had been repaired by riveting another plate, itself badly rusted, on top - and knowing that violent storms could occur in November that would most likely sink some of these heavily laden and uninsured boats, he had serious doubts.

Having gathered the captains to explain the situation to them, he asked them about the risk of encountering a storm east of the Black Sea this season - and the consequences. He was told that the storms might well be violent enough to sink ships, but if ALLAH meant well - nothing would happen. When he persisted in expressing his reservations, the chief of the captains got angry and spoke up, saying to him in a stern tone: “Do you have no confidence in ALLAH?!”

The argument was unstoppable - and he bowed and accepted the contract…. The transport went smoothly - and, a few days after landing in Trabzon, one of the most memorable storms took place, which carried away part of the pier of the small port under construction...

The company gradually equipped itself in this way over the years with other cranes, rolling stock, construction machinery, pyrotechnics, maintenance workshops - and everything necessary to carry out work on such a large scale. The only element that posed a problem at the very beginning of the work was the large “P&H” mechanical excavator mounted on tracks. No transhipment boat available was large enough to carry it. The problem was solved by building a boat adapted to the machine. Once the loading was done and transported to its destination, everything was pulled onto the beach, the boat then sawed in two, and the machine rolled out on its own...

Boats wait for the storm to abide.

A Black Sea “Kayık” being assembled / The P&H mechanical shovel.

The crane for transporting 50-ton blocks, and a derrick / The big breakwater completed.

The port completed in 1955.

In summary:

Construction of Trabzon Port:

Excavation, transport and placement of stone in the dykes with a length of 1250 m: 1,400,000 tons.

Concrete and Masonry: 150,000 m3.

Backfill: 250,000 m3.

Dredging: 1,200,000 m3.

Cost: 23,000,000 Turkish liras (approx. CHF 35,000,000) of the time.

Duration: 7 years. Firms Mitchell EnG. Group and RAR.

Below the house at Boztepe was a large house that belonged to the NEMLIZADE family and was used at the time as a warehouse for goods. The family had built up a huge fortune through trade with Iran and controlled the import-export transiting through Trabzon. The region was also at that time the largest producer of hazelnuts in the world. The cultivation of hazelnuts and tobacco was in the hands of the MURATHANOGLU family. The two families shared most of the town’s commercial income.

The MURATHANOGLU family (about 1948). My parents and JEMAL BEY in the center. Me on the right and my friend ZIYA, 3rd from the left. I forgot the names of his older brother, on the left, and his mother. ZIYA came to Zurich for epilepsy treatment at the end of the 1960s. He died in an accident a few years later.

IHSAN NEMLIZADE had been sent to study in Switzerland, at the international school Le Rosey, where he stayed between Rolle and Gstaad depending on the season. There, he had learned French and the practice of hunting, golf, tennis, skiing and to discern good vintages of wines and other worldliness befitting his social stature. Returned to Trabzon, he only had hunting left, which he assiduously practiced to kill the boredom of idleness, and Raki to face time.

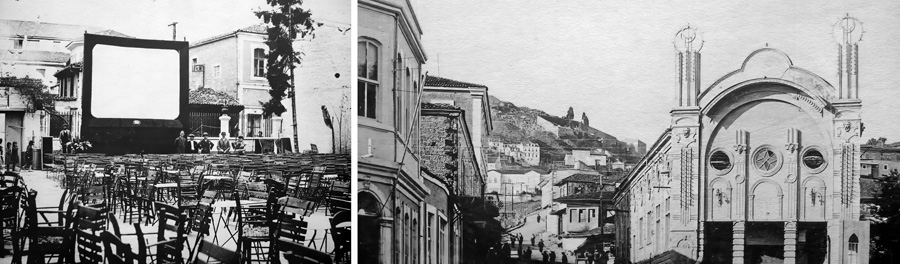

IHSAN BEY frequently sought out our company to speak French (which I didn’t understand yet) and reminisce about good times spent in Europe. He invited us to his residence to taste the products of his last hunt - and which my father dreaded because he was thinking of the poor beast that had been slaughtered in full joy of life - and to show us 16 mm films that he had brought from Istanbul. These films were not sublime in my eyes: for example - a stupid young woman who squirms naked in a giant glass of champagne for a quarter of an hour - boring to death! There would, however, have been much funnier Charlie Chaplins and Buster Keatons to vision!...

Just beyond the NEMLIZADE warehouse and dominating the public park was the English Consulate. A beautiful house with a large terraced garden and a large shaded pergola ideal for enjoying Lime Juice in summer with a view of the sea. My mother often took me there when visiting Mrs. BREEN, the consul’s wife. She was a fine, gentle woman, of very good family, with a choice language and impeccable English manners. I don’t have a precise recollection of the consul. He had incipient baldness, a flushed face, spoke little, and was generally unattractive when he did. His wife must have been very vulnerable to passing predators.

IHSAN BEY was a big consumer of Raki - or other similar spirits when he found them - and very often “under the influence” when we met him (he died in his nineties...). My parents also wondered how he was able to bring back so much game from his hunting trips - and that he didn’t have an accident. When the Australian trainee MANNING arrived at the English consulate, he found there an ideal companion to celebrate. One night in the wee hours of the morning - MANNING’s jeep honking under the window and the two drunken friends looking to invite my parents for a ride... all the better if it was only my mother who would come... The situation continued thus one summer - until the moment when MANNING focused his attention on Mrs BREEN and left with his Jeep, and her, for his country and an unknown but hazardous future - especially for her...

When we lived in the Boztepe house, my parents had hired “JULA” to take care of the kitchen. She was a Polish – Ukrainian woman who had been brought back from her country at a very young age by a Turk from Trabzon after the first war. A nice lady whom I liked, and who served us meals that included cabbage and potatoes a little too often - but of whom I have fond memories. She spoke a fairly rough Turkish mixed with the Laz dialect and with the addition of Slavic-style “ni” endings to adverbs. So, for example, the word “burada” (“here” - in Turkish) became “burdani” and my mother had a lot of fun composing sentences in Turkish in this way.

For housework, we periodically had the visit of the “BADJI”, a taciturn lady of pure Laz ethnicity with a marginally understandable language, and who had immutable principles concerning cleaning and tidying up which she practiced in an expeditious manner. My mother quickly learned to let her do and to restore the situation after she had left.

JULA had a daughter, MUALA, with whom I sometimes played. She was a little older than me and sometimes served as a “babysitter” when my parents were away in the evenings. She was of a very serious nature and did not easily understand a joke. So, I could tell her the most incredible stories before she started to suspect my game. I claimed to know how to play the piano (my mother had given up on teaching me after a few unconvincing lessons…) listened to me hitting random keys rapidly, dubiously, perplexed. I also have very fond memories of that honest and kind girl.

In 1953, my father rented a beautiful house recently built by IHSAN BEY in the Gazipaşa district. We had remained good friends. I last met him in 1966.

We visited Istanbul more frequently than usual during the port construction period. My father had to submit reports on the progress of the work and settle the various administrative points with the RAR Company. Istanbul was then a much more cosmopolitan city than it is today - comparable in many ways to other European capitals. There was a strong Greek community, followed by French and English. The Jews were numerous but kept, as often, a low profile while dominating certain sectors of commerce. Even the Armenians were present - some had however moderated their visibility by removing the “ian” from their name. We met descendants of the “white” Russian Diaspora, faithful to their stereotype with their Slavic accent and all claiming to be from the nobility. The “Russian countess” was not only a topic discussed in literature, but met in person at every somewhat social gathering. French was the dominant foreign language and the city still had more than 20% Christians - compared to just about one percent today.

With KAHRUMAN, a friend in Gazipaşa in 1953.

The Gazipaşa house, in 1953.

During those excursions, we used to stay at the “Büyük Londra Oteli” (Grand Hotel de Londres - modern view). A beautiful end-of-century hotel (from the 19th century) run by a Greek family. On our arrival, Mrs. KAFATOS received us with dignity and assigned us one of the most beautiful rooms - generally the one on the 2nd floor which had a balcony flanked by columns sculpted in the shape of caryatids. From the street, one reached the reception by a ramp of stairs. To the left was a fairly dark dining room. Behind the reception, a complicated and capricious elevator whose swinging, sliding, grille and concertina doors had to be closed very carefully if you wanted to avoid being stuck between two floors. Arrived at the floor, it was necessary to close everything and press on the dismissal button of the elevator. Otherwise, an employee had to take the stairs and arrange for the next passengers.

The “Londra Oteli” in 1993. Nothing has changed in 50 years.

We used to have dinner at the hotel. The Italian headwaiter, EMILIO, a short, stocky man in his white official jacket, had taken a liking to the child that I was, and each time had a plate of Italian “risibisi” abundantly garnished with peas which he knew I loved specially prepared for me. I pay tribute to his memory!

There were also the guests who resided at the hotel.

A former English officer in India, MAJOR BRADLEY, who eat with dignity at a nearby table in his two-tone brown tweed suit, and who exchanged a few words through his large moustache with my parents. His military retirement pension was insufficient to survive in England, but he could still afford the Londra Oteli in Istanbul.

More mysterious was MONSIEUR MALZAC. A middle-aged Frenchman in a gray suit who sat a little further away. My parents had tried several times to strike up a conversation, without much success. This taciturn man wore a large gray beard cut into a rectangle that he held two millimetres above his soup - and never wet it. As his baldness was advanced, my parents often speculated in low voices about the authenticity of this beard. One day, to get to the bottom of it, I got up and grabbed his beard with both hands and pulled with all my might! It was real!

I don’t have a clear recollection of what happened next - but there was a lot of commotion…

Breakfasts were served in the room. Relatively minimalist considering the class of the hotel. My father then looked out for the passage of the “simitji” - the seller of “simits” in the street. Simits are delicious buns shaped like a thin ring and covered with sesame seeds before baking. Roasted, they become absolutely tasty. The man used to sell his wares strung on a stick and paced the sidewalk. Cut lengthwise, buttered and spread with jam, these mini sandwiches were a wonderful addition to the usual breakfast.

The risi-bisi and simits were for me exotic delicacies - not found in Trabzon. Another gastronomic treasure could be tasted at the Swiss Club’s restaurant. It was located not far from the hotel on a shopping street. A relatively large place, but where we were often the only customers when we went there. They only lit the lamp above our table and the meal took place in an oasis of light surrounded by darkness. It was only much later that I understood that this practice illustrated Swiss economic pragmatism.

But they served “vol-au-vents” and Viennese sausages! What a delight!

The return to Trabzon was by sea, the cabin full of goods not found in those wild lands - canned food, clothes, a toy or two for me and my friends, specific orders placed by neighbours or colleagues of my father and gifts. I liked coming home, away from the noise and the hustle and bustle of the big city. And to be able to have fun again with the gang of children my age in the street without being constantly in the company of adults who frequented off-putting places and talked about things without any interest!

The group of friends, and some girlfriends, with whom I played were the children of the families of the district. Modest families, sometimes poor. I was often the only one wearing shoes. They knew I was the son of “CRAMER BEY” who was building the port, and some had their father who worked for the company. But they were straightforward and loyal - there was no sense of hierarchy between us. We met in a vacant lot a little higher on the Taksim Sokak to play ball, fly hexagonal kites that we assembled with three sticks, string and tissue paper that we glued with wet flour, we practiced throwing stones and making slingshots with strips of rubber salvaged from old inner tubes, a forked stick and a piece of leather to hold the pebble. This last discipline, where I had acquired some proficiency, earned me some trouble years later, with the Lausanne police in Switzerland...

I am grateful to my parents for giving me so much freedom as a child, and for not locking me up in a western golden prison. They were both born in the country and knew the moral uprightness of those who some people occasionally described with cynicism and contempt as “low-class people”. I now recognise how my father proceeded, treating the simplest of his workers as an equal, and with fairness, and thus gathering together a team willing to sacrifice themselves to get the job done no matter how difficult it was.

There was the worker named YASAR - which in Turkish means “he lives”. Turkish first names are very colourful. For example, the common female name AYSEL means “moon that lights up the flooded river”, or KEMAL which means “immaculate white”.

YASAR was a simple man but appreciated by all for his gentle character and was endowed with exceptional physical strength. He worked in the quarry where the rocks were taken to build the harbour dykes. After each blasting there remained rocks in unstable balance that had to be dislodged to secure the site. YASAR was then sent there, he placed himself under the rock, and with his crowbar gradually cleared its base. At a moment that only he could determine, he would step aside and remove the last stone that would make everything crumble.

One day, he learned that a man was paying too much attention to his wife who had remained in his village. He then let it be known that on his next leave, he would go up to the village to settle the account with this individual. The lover had meanwhile gathered seven of his friends to defend him when the time came. YASAR came up a week later and very seriously beat up the eight men who were waiting for him. So much so that they filed a complaint with the criminal court of Trabzon…

My father invested himself considerably during several sessions of the trial to defend him, and YASAR was finally exonerated. He then gave us unconditional gratitude, and one day, in return from his village, he brought us a sheep as a gift.

I remember that good beast with a white coat and a black head who assiduously browsed all day long on the wisteria, roses, camellias, hydrangeas, gladioli and everything it still found in the vegetable garden. One day, my father had it taken to a vacant lot near the construction site where the animal would be “more at ease” and where, to everyone’s regret, it “disappeared”.