The Interviewees

Interview with George Galdies - December 2022

1- When did you decide on embarking on this book of ‘Smyrna on my Mind’?

In March 2017, George Poulimenos my co-writer of our Smyrneika Lexicon, asked me if I had finished going through my late father’s ‘memoires’. My answer was that I had not really done much, especially as we’d been recently blessed with two new grand-daughters from each of our girls.

Effectively however, Poulimenos’ question reminded me that Smyrna Levantines of my generation were rapidly fading away and that I should put down on paper all memories of Izmir in my mind. Craig, you were of the same opinion too, and provided much encouragement.

But there were a couple of more years of being busy with other matters such as business and several email exchanges between myself, the LHF, Poulimenos, and Achilleas Chatziconstantinou on various queries from former Smyrniot families, buildings, and events, before I could assiduously sit and decipher my father manuscripts.

Around that time too, I was (still am) very keen on the idea of reconstructing a church within the Parthenon of Athens, to be dedicated to the Parthenia par excellence: Virgin Mary, Mother of Jesus-Christ. After all, there had been a church there from early Christianity until the 6thh Century AD when Athens was assaulted by hostile forces once again!

There followed much correspondence between Church authorities of various denominations and myself, and even a visit to the Orthodox Patriarch of Athens. As expected, this idea led nowhere with the religious. There were too many other preoccupations to be dealing with apparently. Too many new movements that were emerging in America were also taking root in Europe and around the rest of the world. The status quo should not be disturbed I thought.

My project of a multidenominational Christian worship centre within the currently void interior of the temple structure would have created jobs and splendid opportunities for architects, designers, and artists to shine. Although stunningly beautiful and historic as it may be, with my project this site would be transformed to regain the purpose for which it had been originally erected, and regain a new dynamism instead of the pedestrian photo opportunities it now offers to tourists.

Christian Church authorities were politely declining to tackle my suggestion. I guess they probably thought I was a foolish, if not a deluded eccentric. The Parthenon had therefore to remain an antique (and in my opinion, a passive) symbol of European civilisation. All this kept me quite busy.

By 2019 we saw the arrival of Covid 19 and what I considered the irrational lock-downs as imposed by panicking authorities. Such lockdowns made travel impossible and as a consequence I had to close my company. On the positive side however, these forced home confinements afforded me the time to concentrate on my father’s writings and merge them with my own.

By October 2020 Poulimenos started his “1922 Smyrna Fire project” and requested any material I could provide on the subject.

I now had a sense of urgency if my book was to be released to commemorate the 1922 Smyrna events. I chose to use the title as Smyrna On My Mind. Publishers were duly contacted with the abstract. By September 2021, most replies were positive towards the text but, in their opinion the subject matter was not deemed to be of wide enough interest to make the project viable for them. On the suggestions of friends and colleagues I decided to follow the self-publishing route.

2- A good section of your book is from the notes and diaries of your father Peter Galdies, who clearly was a good observer and recorder. Did you have access to the writings of any other relatives of earlier times? How did you decide what to put in and what to leave out of your father’s clearly extensive writings?

Sadly, there are no writings of other relatives of earlier times. From them I retain only what I had been told or conversations that I might have heard at an early age.

Of my father’s own writings, I included the quasi totality of these, except for a very few elaborate details which I judged my grandchildren would not comprehend. After all, I was writing this book for their benefit.

3- There are a number of group photos such as Carnival photos in Izmir where you have identified a number of people. Would you welcome input from readers to help identify the other faces or other facts you have covered in this book?

Yes, I would welcome such input.

I am adding the photo below (1955?), inviting readers of this interview to identify individuals they might recognise. The third boy bottom right is me, still holding a chou a la crème in a white wrapper that I was presented with by HE Mgr Descuffi our archbishop (centre) for reciting a small poem dedicated to him and with the final teasing phrase: “but all I desire is only a little chou a la crème!” - here is a link to excellent photos of St Joseph’s on LHF:

4- There is a section of the book covering the burnt areas of Izmir from the catastrophic 1922 fire called Ta Kamena. When you were a child to what extent was this area still barren and was it seen as a place to avoid at night? Do you think the Fair site it has become was the best use of this barren land?

As I tried to describe it in the book, my earliest memories are ones of uninterrupted views from our house all the way to the ‘Çatalkaya’ hills called ‘The Two Brothers’ in the westerly direction. The land in that direction was still barren with a few exceptions of one or two houses still there in the proximity of the compound housing the French Hospital and School which were also still standing. My father’s sister Aunt Maria Consolo and her family lived in one such house. Another house was that of Joe Serra, the hunter, and a very few others.

Beyond the French Hospital there stood the Gazi İlk Okulu elementary school dedicated to the ‘Gazi’ (Ataturk) i.e., The Martyr’s Elementary School that had been built in 1933 (?). The school stood as if rising amongst the devastation to its North, but to its East and West there was the new quarter of European Art Nouveau style two story dwellings quarter being developed. These new ‘apartment’ buildings were all surrounded each by their own little gardens.

My aunt Bero and her first husband teacher John Caldwell, lived on the first floor of such a building, facing the school. By the time I started nursery school, Talat Paşa boulevard had been laid cutting through the Kamena (Yanıklar in Turkish) from our house all the way to the sea- front meeting the Cumhuriyet Bulvarı (the former Rue Parallele).

The view from our house to the South was the substantial building of Turkish State Monopoly called the Tekel. This used to be illuminated with myriads of electric bulb lights on every state occasion. Almost next to it was the former English Seamen’s hospital which had become a Turkish state school for deaf children. From there on there was the Ziya Gökalp Bulvarı leading past the Namık Kemal High School and unto the Kültür Park. All this area was being developed for housing by the Vakıflar Bank.

What I describe above was effectively an open play ground for us as children. In Lent we used to graze our sheep, the rest of the year we were free to roam and watch the routines of the construction workers, from digging of foundations to seeing the new homes emerge.

Facing North and Northwest, i.e., the quarter at the back of our street and all the way to the Punta proper, this area formerly also known as the Italian quarter, had been spared, and the streets were the very same as during the Ottoman, pre-1922 days.

At night the vast area of the Kamena as well as the Punta were patrolled by night watchmen called Bekçi. In our Levantine parlance we had retained the name “Pasvanti” which was derived from the Italian ‘passa avanti’: pass forward. During Ottoman times the Turkish word was Pazvant, later changed to bekçi or watchman.

There was a bekçi for every two or three streets, and they would communicate with each other by way of whistles. These were mostly Acme Thunderers. They used different tones according to circumstances. The bekçi were our friends and would receive presents at holidays. These watchmen would challenge anyone on the street past midnight. In any case, there was very little street lighting and there was practically no reason for anyone to be out and about with the exception of Carnival time and Ramadan.

I may add here that in some but rare divorce cases the bekçi were invited to witness any cases of adultery being committed in order for the husband or wife to obtain a rapid divorce!

Regarding your question on the Izmir Fair site aka, the Kültür Park. This in my view is the best monument that the municipality could have created as a remembrance to the peoples, and their homes, businesses, and churches on those grounds had been erased for ever. I wish a commemorative plaque could have been laid there this year, to mark the centennial anniversary of the fire.

This formerly barren land as you call it, was transformed into a treasured oasis of greenery amidst an ever-growing city. Long may it remain so, and avoid falling into the trap of this beautiful spot becoming a concrete jungle. As mentioned in the book the annual international fair and the valuable museums sited in the Kültür Park were in my childhood the most important windows unto the world for us. Here is a link to pre-and post-1922 photos of Alsancak.

5- You were keen on amateur dramatics with friends at the college of St Joseph you were a student at in the 1950s. Were you also involved or in the audience of the ‘Playgroup’ theatre group that took place at the Anglican Church of St John in Alsancak and who were the main movers in that gathering?

In the early seventies I was a member of the board of the ‘play reading group’. Notice that this was a casual social group of friends who, as amateurs, would produce, direct, and perform stage plays according to the perceptions and fashions of the time.

As I remember, before I left Izmir; my fellow board members were: Dennis Hallam (RN?), Richard (Dickie) Pariente Keith Stokes (RN), Gloria Smith (US Consulate), Ann Freeman, Anne Hayes (?) … previously there had been Suzie Whittall, Reggie Gallia, Helen Borg,… This is a link to photos of the “play reading group” in the 1960s and 70s.

All in all, there would have been over 150 members or regular attendees. These were mostly English-speaking Levantines, with a sprinkling of UK and US Forces personnel, an equal sprinkling of UK ex-patriate mostly tobacco buyers, teachers, and, well known Turkish anglophiles such as the Mücahit Büktaş family, Mr & Mrs Çobanli, Mr & Mrs İstemi Gürel…

I was glad to see a few years ago that this group was reborn in 2008 as the “İzmir Amatör Levanten Tiyatrosu” and is apparently still going strong. Long may it thrive.

I don’t wish to close this section of theatrical plays by Levantines. Here are a few photos of performances at the Italian Ivrea Sisters’. Most photos date from early 1950s.

On this picture below left of picture to right: Polino Mille(?), Mafalda Consolo, Maria Sponza, a Miss Russo(?), Centre: Eda Tornaviti, Silvio Sponza, Knelling down Evelina Sponza, second from right: Lea Missir.

Circled in red: Maria Sponza, in green: Evelina Sponza, orange: Elena Consolo, in white top centre: Eda Tornaviti.

6- You were also instrumental with the late Alex Baltazzi, and Athens based George Poulimenos in drawing up and publishing a ‘Smyrneika’ Greek dialect of Izmir booklet, a language clearly under danger of being lost within a generation. Was the main drive to publish this work its vulnerability?

When I generated the idea for the creation of “A Smyrneika Lexicon”, my main concern was, and remains, that future generations should have access to materials that best depict the social history of Smyrna of that period. The idea was to keep alive as much as possible, the language of the ordinary people as spoken in the streets and markets, and Port.

Having said that, both Alex but especially George P, were each in their own way, instrumental to make this 170-page book in the original Turkish publication, (and a 211 pages American hardback version,) a valuable testimonial to Smyrna’s richness of expression which is bound to disappear due to lack of usage.

I need to stress that this work would not have been realized without George’s most arduous and dedicated technical help, the support of the Izmir Chamber of Commerce, and the backing of the History Foundation of Turkey and its visionary Director Dr Fikret Yilmaz.

As a final note on the subject of dialects; Cypriot Greek in London, as with Rum/Romeika Greek in Greece and Istanbul, are all gradually also sadly losing their usages for obvious reasons of dilution.

7- You include a section in the book of the now non-existent Kalabaka summer colony for the Christian children of Izmir run by Padre Giulio, and presumably you were also one to experience this vacation and immersion in Christian focus. Do you think this was one of the important elements of inculcating amongst the children the Levantine and Catholic identity and therefore its loss is a blow to the future viability of the community?

Padre Giulio involved me at arm’s length in his ‘la Colonia’ project whilst I was in my mid-teens as an accident of the fact that we were friends. We seldom talked about religion, especially our Catholic faith. He was a good mentor about life in general and had confided that his dream was to set up a summer colony, of the type that still exist in Italy, France, etc where they are usually ran by municipal authorities.

Up to that time, many who did not go to stay at beach resorts during our long summer holidays, had to rely on their parents for day trips. Photo below is of Mr Andrea Sponza with daughters Maria on his right, and Evelina on the landing jetty of İnciraltı bathing resort (circa 1940s).

However, the Italian Ivrea Sisters used to organise coach and ferry-boat twice weekly parties mainly to Izmir’s city beaches of İnciraltı.

Such outings were quite appreciated as we enjoyed the collegiality and the strict discipline of the Nuns, especially Suora Valentina who would keep an eagle eye especially on the boys, and stop any misdemeanours. They would allow us to hire rowing and sailing boats however provided the boatman would keep an eye. But by the time Padre Giulio arrived in Alsancak, the good Sisters were already getting on in age, and no longer had the energy to control little crowds of sometimes unruly kids.

The purpose of the Summer Camp of Kalabaka was to provide buys and girls of Izmir parishes an enjoyable experience of summer holidays on the beach. By the time the project had reached its maturity I had lost complete interest, and busy with work and other activities. From what I know Miss Donata was in charge of Kalabaka, and not being of any religious order, nor for that matter a Levantine, would not have been qualify to ‘inculcate’ any reckonable Levantine identity.

I expect she would have conducted morning and bedtime prayers, and said Grace at mealtimes. There would have been Mass on Sundays. I am sure the language spoken at Kalabaka colony was Turkish, and to a minor extent Italian. In my view any sense of a Levantine identity as such was already fading away, mixed marriages with non-Christians were no longer unusual.

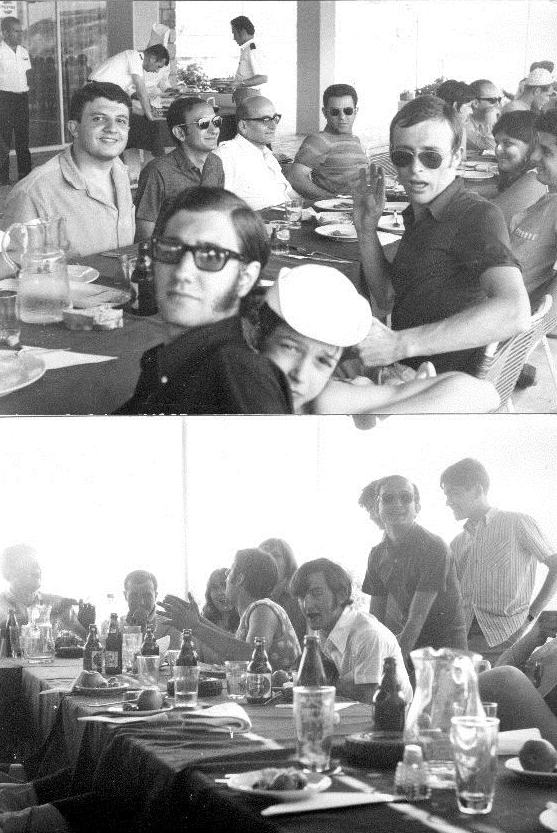

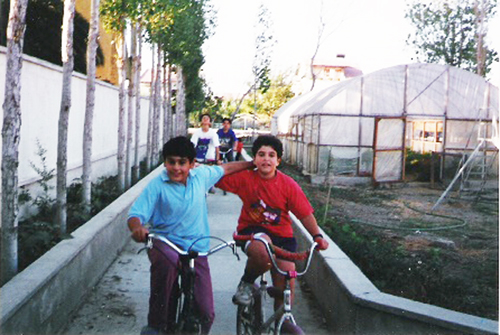

By the early 1960s our Levantine youth were well past the Kalabaka days. By now we used to attend weekly Mass on Saturday evenings at the Santa Maria church, and this service was immediately followed by a kind of disco held in the little church hall. The whole thing was under the supervision of the Franciscan curate in charge. Sadly, his name escapes me. We also used to organise outings to the newly emerging resorts such as Gümüldür. The attached photos depict one such outing. top photo left to right: Renato Sponza, myself in sunglasses, the curate, Polino Bioni RIP, and facing us I recognize Cedric’s brother Erol Hale in specs, and a Frenchman Michel Imbert? who eventually married our friend Chantal Dermond. Sadly, I cannot recognise the people in the lower photo, except for myself standing.

I also attach below some photos of Kalabaka which you had previously provided me with. They probably originated from the Dominican church archives. I start with this picture of late 1950s? showing left to right; the Fathers Salvatore, Vincenzo, Giulio, and Sebastiano.

Vincenzo Baptized me, Sebastiano was my confessor for a while, Giulio was a good friend and mentor, and Salvatore; a new arrival from Italy, was great fun. As I remember, he admired beauty and used to say something like: ‘a priest can admire but should never desire!’

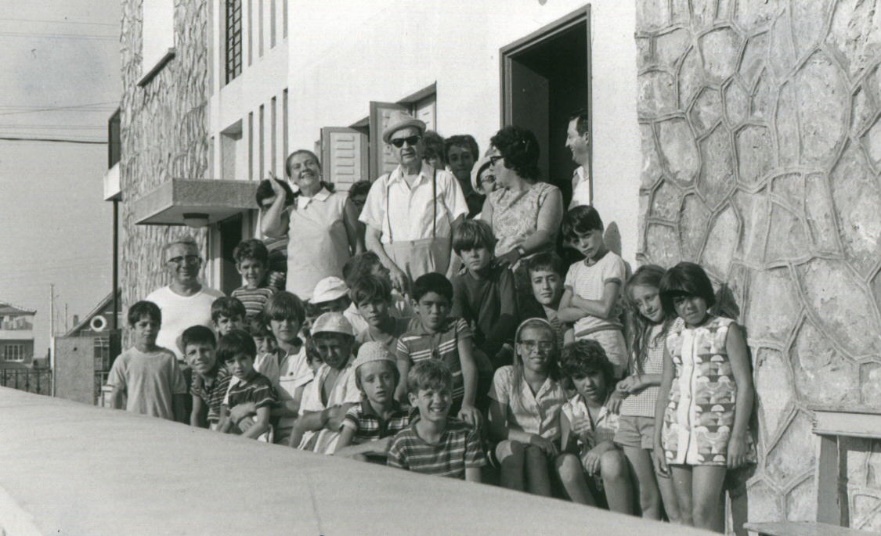

Colonia nearly built.

A visit by Archbishop Boccelli.

Below:

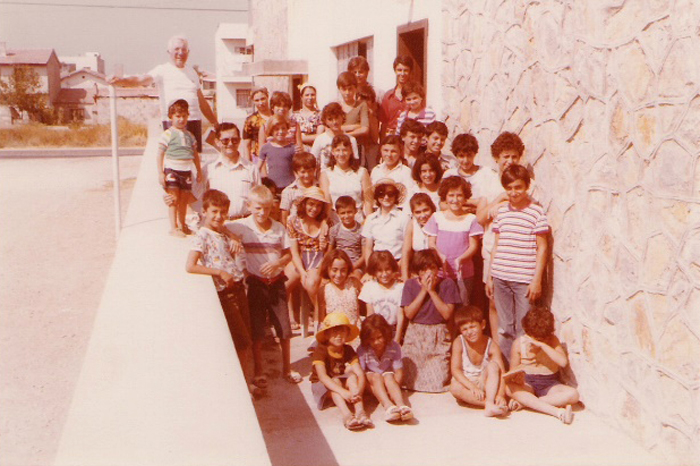

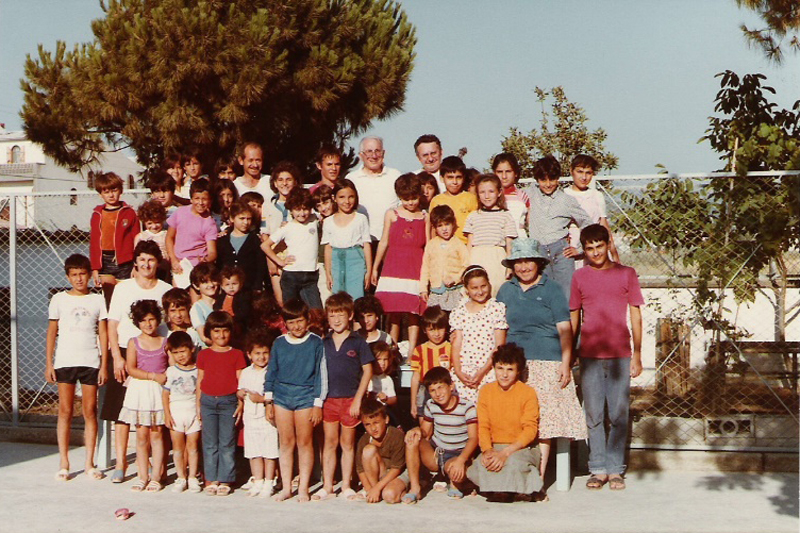

Group photos at Kalabaka,

Constructions in the background depict the rapid development of urbanisation.

8- Have you received feedback from family and friends on this book and from this has new material or corrections have come about? Could there be a future revised or expanded edition from this outcome?

My children loved the book, especially as they grew up being very close to my parents and could quite relate to the narrative. They even suggested that it warrants being made into a movie! Other members found it harder to follow the sequence of events and would have preferred a chronological account as opposed to my chosen alphabetical presentation.

As for friends, those acquainted with the Smyrna story found it very useful to have such a first- hand account, others said it was a true representation of Smyrna of the times. Other readers, for whom even the name of Smyrna was unknown told me they were fascinated to find out that such history had existed and expressed frustration that, let alone their school days of the 1950s and 60s, they had never encountered such accounts even in their adult lives.

Others told me that they’re surprised that my book had not been published, especially in Turkey, Greece, nor even Malta as the latter takes a prominent place in my story.

I’ve received no corrections as yet, but remain open to such, as I am indeed considering a future and expanded edition.

9- Would you characterise the 1950-60s as the ‘golden age’ of Izmir when prosperity finally flowed with influences such as the NATO presence, new night-clubs and an increasing taste for the art of living?

That is probably a fair assessment for the period, certainly for as far as I am concerned. Although in the preceding 1930s-40s the ‘Levantine’ community of Izmir was still possibly larger than it had ever been, and this community was still the mainstay of clerical work in the all-important export activities of the Aegean.

Judging from photos of 1930s to the pre-Second World War years of 1940s our community had ample opportunities to enjoy themselves with serenades, pleasure trips to the countryside, pilgrimages to ancient Christian sites, balls, and endless religious feast days. This is a photo depicting one such occasion, probably at Meryem Ana sanctuary, or possibly at the then popular excursions site of ‘Nymphio’- Kemal Paşa. In here I only recognise my father in the middle row, lefthand side, and my uncle Anthony middle of second row up.

Being more or less fully employed, and in spite of being subjected to restrictive and discriminatory laws causing much apprehension, there was a certain well-being among the Levantines. Reading my book, one can correctly deduce that even after the 1922 fire, Izmir could still be outlined as a conurbation of four basic groups living generally inside each their own defined areas, but in reasonably good harmony albeit within unwritten, or perceived boundaries. Broadly speaking these were:

The previously Ottoman Turkish families predating 1922, together with Turks from Crete; these were all still amiable to Smyrnaean cosmopolitanism, or what is called today pluralism, and Western ideas. On the whole these were senior civil servants, military or large land-owners, some of whom are descendants of the tribes first to conquer Asia Minor over some seven hundred years ago.

Then, a second group of ‘neophytes’ i.e., refugee Turks from the Balkan wars and devoted to Islam, perceptively provincial, and largely anti-Western. This group would take a long time to mix with the others. I would add to this group Kurds from the east, and Lazes from the Black Sea areas.

A third group comprising Ashkenaz Jews that had fled the Bolsheviks and Sephardim Jews that had arrived from Spain in 1492. Both groups sociable, especially the Ashkenazim whom I feel were to inspire many socialites, even amongst Turks and Christians.

And finally: Western expatriates and local Christian Levantines, the latter being a mix of European origins, plus a very few Armenians and Greeks who had acquired European nationalities. I believe this fourth group of citizens enjoyed the most prominent profile. They were not shy of coming forward in adopting the latest Western ideas of creativity, sponsoring trade, shipping, industry, leisure, travel, and banking. But all within the restraints of the republican laws applicable to foreign residents.

As the years went by, this joie de vivre of the Levantines was gradually being matched and surpassed by the emerging and rapidly prospering modern and visibly secular Turks who had enthusiastically embraced Kemalist reforms.

However, it is my opinion that this wave of secularism that was generating overall well-being has been also responsible for the slow demise of the Franco-Levantine community. Religious practice which had been keeping the community together, was now gradually being eroded. As elsewhere too.

The ease and feeling of security nurtured by the arrival of NATO, and the wealth generated by growing business opportunities and nascent industries, was indeed reflected by modern apartments, large American cars, new restaurants and international standard night clubs, and; by then, also frequent foreign holidays and travels by all to Europe and America. The city could not help but re-acquire its Western-like identity.

All four groups mentioned above were now being amalgamated. In my opinion, the need for the spiritual security/comfort blanket provided hitherto by the concept of a ‘Levantine community’ is henceforth all but sadly extinct, or on the way to extinction.

10- Your father’s memoirs which you extensively transcribe in the book include the events before, during and after the fire of Smyrna. Even though these events happened 100 years ago, was it difficult for you to process the horrific things this account recounted of the human drama and destruction? Do you think the ‘official’ story from both sides is still to be told and Levantine eye-witness writings as potentially being the most reliable in this highly politicised debate still going on in some circles today?

Surprisingly, it was not difficult to process the horrors of war, since parents, grandparents and friends had often depicted what they, and millions of other had gone through. However, it was an advantage to read in a linear way my father’s notes, as opposed to the sporadic references and comments he used to voice in certain circumstances.

I had honestly underestimated the degree of hardship in his early childhood before reading this.

My book depicts what in French used to be called “La petite histoire”, i.e. individual stories and details within ‘official’ History. Eyewitness accounts should very much be taken into account as first-hand illustrations to support the official story. I prefer that our world will continue to exist as a collection of diverse communities rather than the ‘beige’ mono-chrome open world that idealists pursue. The ‘little histories’ of communities, when duly promulgated, should continue to keep our world diverse and enriched by its past.

11- You have spent half of your life in England yet clearly you haven’t broken your friendly and emotional ties to Izmir. Are there particular dishes or other aspects of habits that you still carry with you?

I’ve actually spent three quarters of my life in England, having left Turkey for good near the age of 25. In the course of the fifty years of absence from the Aegean shores, I maintained an emotional link with Smyrna thanks to the many factors that had forged and enriched my early years there. Most of these are mentioned in the book, but as any romantic would be there is also the love of the land and its history that lingers.

In my early decades in the UK I’d been blessed to have both my parents living in close proximity, in the same village. My mother would hardly let a day go without insisting we collect and share some of her home cooking. Each Sunday we had afternoon tea with the extended family when Smyrna pastries and cakes provided made sure that no Smyrna specialty would be longed for.

One particular habit I’ve retained betrays my love for Turkish rugs and carpets. This habit is to reverse a rug to check the type of weave, knots, etc. also identify the country of origin. Please note I am absolutely no expert. Once in New England I was invited at a leading industrialist’s home, and apologising for my bad manners I could not resist checking the splendid carpet in my host’s study. Caught in the act I had to venture Keshan? as its origin, and thankfully it was indeed Keshan, much to my host’s relief and mine.

The story of the book covers I’d chosen is a demonstration of my love for carpets and of the metaphors that the carpet motifs display. In the book I also mention that I always have Smyrna rugs at the foot of our bed, so my feet touch Smyrna-ground when I first emerge in the morning, just like Onassis did, but without his fortune!

12- During the 1950s to the 1980s there were a whole collection of British and American tobacco buyers based in or regularly visiting Izmir, adding to the cosmopolitan mixture of the city. Did you and your family have much interaction with these expatriates and any names you remember?

My father’s social involvement had always been gas-oil and petrol related, and later US/UK military social interaction. As for myself except for the odd social occasion, and apart from my consular duties I had very little to do with leaf buyers, although some of my Levantine friends did. Thinking about it, I would have rubbed shoulders with some either at the ‘play reading group’, or some dinner party, or a charitable function. I suspect these tobacco dealer expatriates were responsible for coining the ‘Levantines’ epithet for us the permanent residents.

13- Clearly the rise of the internet / e-mail technology in the past 20 years has helped you fill gaps in knowledge in terms of distant cousins and former neighbours in Izmir. Is this process still ongoing?

I’ve been lucky that my cousins live or lived in easily accessible locations be it in the London area, or Lyons, parts of Italy, and we have been able to meet quite frequently, as well communicate via the internet.

But there still remain several descendants of my parents’ cousins yet to respond, or to be traced around the world.

14- Photos showing the visit of the late Queen Elisabeth visiting Izmir in 1971 show a healthy strong crowd presumably mostly Anglo/Maltese-Levantines and diplomatic staff. Can you remember some of the prominent names who were present there when your father was the acting Honorary British Consul?

At that time, my father was not the ‘acting’ Honorary British Consul, he was the Honorary British Consul for the Aegean Vilayets of Turkey. I was British Vice-Consul part of the staff of Consulate-General in Istanbul, and seconded to the British Consulate of Izmir. I reported to the Consul-General, Istanbul and on the dotted line to the Embassy at Ankara for business on the southern shores as Ankara had a rather small Consular section.

I shall endeavour to recall names amongst the guests, but there is hardly any diplomatic staff in that photo apart from my father. In fact, I cannot recall any Diplomatic staff specifically, apart from HM Ambassador and Lady Sarell during that visit.

Some names that come to mind which I append to the photo below. The well-wishers are members of the British community made up mainly of long-term British residents of English and Maltese origins and an equally good mix of some business expats, and a near dozen families of British Forces NATO personnel. I hope to produce a full description of that event in some future writing.

15- Were newspapers and their consumption an important element in your family’s daily routine in Izmir and were there particularly titles and columnists you or your father particularly followed?

Yes, newspapers were important. The official gazette and the Ticaret newspaper needed to be checked every day as they were publishers of new legislation and regulations. These had a bearing on how to conduct business, import quota allocations, public tenders, etc. it was equally important to gauge the trends of the day towards the politics with the West, and to put in bluntly to also gauge how safe were we in the face of extreme ill feelings from some quarters towards us, foreigners.

Apart from that the only daily of interest to us was the Yeni Asır, as mentioned in the book, which focused on our local, even community news, not to say gossip as in who danced with whom and where.

Our other interested focused in the British newspapers to be found at the Consulate, and subscriptions to French weekly magazines for my mother, Paris-Match and, The Readers Digest for the family. My Grandmother Eleni used to receive a Greek newspaper and a weekly “O Thysavros” by post from Athens. Finally, there was the French language Catholic monthly Presence from Istanbul and the Journal d’Orient also from Istanbul.

As for columnists favoured? I don’t think we had anyone in particular but Cemil Devrim, Haluk Cansın, Sukuti Tukel come to mind. Perhaps Selçuk Yaşar? But not so sure.

16- How often do you still go to Izmir and how would you characterise the surviving cultural elements of Levantine culture in that city?

I wish it was more often, I haven’t been there since 2018. Sadly, each of my previous visits there only revealed the decline of any cohesion that might have survived the 1970s period which I knew.

What I discovered during those relatively recent visits is that there seems to be a certain lassitude towards any community spirit. It seems to me that the vestiges of this community are made up of disparate and tiny clans made up by family, or seemingly close parochial bonds.

The commonality of Levantine-Smyrna Greek language has now given way to Turkish. Levantine-Smyrna cuisine together with a much-diminished Catholic practice seem to have remained as the weak elements of Levantine culture.

As everywhere else in the world here too the Levantines seem to have succumbed to the social engineering trappings of Internet social media, and TV adverts. Having said that, I was much heartened to see that our old English Play Reading group had somewhat survived under some new format, and had been producing by all accounts some great plays.

I live in hope that the Levantine Heritage Foundation’s branches in Istanbul and Izmir will grow to make up for the years that were lost during our cultural near-oblivion of the end of the last century.

Nevertheless, I believe that thanks to the arrival of migrants, be it temporary Western expatriates, or those seeking refuge from troubled areas of the world, this influx is showing that a Christian community, albeit not entirely Franco-Levantine, will continue to thrive in Izmir. I believe that we should consider the Syrian and Iraqi refugees as true Levantines in the original sense of the word, and welcome them as a fresh addition to Izmir’s rich and everlasting Melting Pot!

Interview conducted by Craig Encer

Sample pages of ‘Smyrna on my Mind’: