The Interviewees

Interview with Dr Sercan Sağlam, March 2019

1- Many port cities along the Mediterranean had a similar geographic outlook to Genoa and Venice, but those two city states were clearly far more successful than other rivals ranging from Pisa to Barcelona. What do you think were the ingredients for these cities to look outwards way early in their medieval development and create these merchant empires way bigger than their own territory?

Because Venice and Genoa were both surrounded by impassable geographical barriers as well as stronger states, therefore the seas were the only possibility for their survival. As a result, they have needed to rely on their naval skills more than any other state but it is also true that these maritime republics both had deep rooted naval traditions, which was the beginning of everything. The rivalry between Venice and Genoa was proverbial during those ages. Genoa itself was limited by the mighty Ligurian Alps to the north and also the many kingdoms that lay beyond, therefore the nation was almost trapped into a narrow strip of land. Correspondingly, they have benefitted from their seamanship, expanded through the inter-connecting seas and then established a large commercial network.

2- Officially Catholics were barred by the Papacy from trading with Moslems as they were seen as the biggest threat to the ‘Holy Lands’ and Eastern Europe during the Middle Ages. Did Genoa and others fudge this distinction or did they feel trade over-rode moral and theological considerations?

I think the Genoese were a truly clever and pragmatic nation. As naval trade was the only option for their survival, perhaps they have needed to set their own secular balance between religion and business in order to keep a thriving economy. It can be argued that on some occasions, foreign traders were helping Genoa more than the Papacy, therefore the Genoese have most probably needed to make a pragmatic choice. Nevertheless, they always kept a strong Catholic identity in spite of being away from their home. It was also visible on the colonial heritage other than churches, as they have often placed crosses above their fortifications and dedicated towers to saints, demonstrating the everlasting motivation of the Genoese above some professional decisions.

3- When dealing with Galata / Istanbul is it clear how to define and separate Genoese buildings as clearly this community must have also adapted and modified buildings from the Byzantine urban fabric they entered?

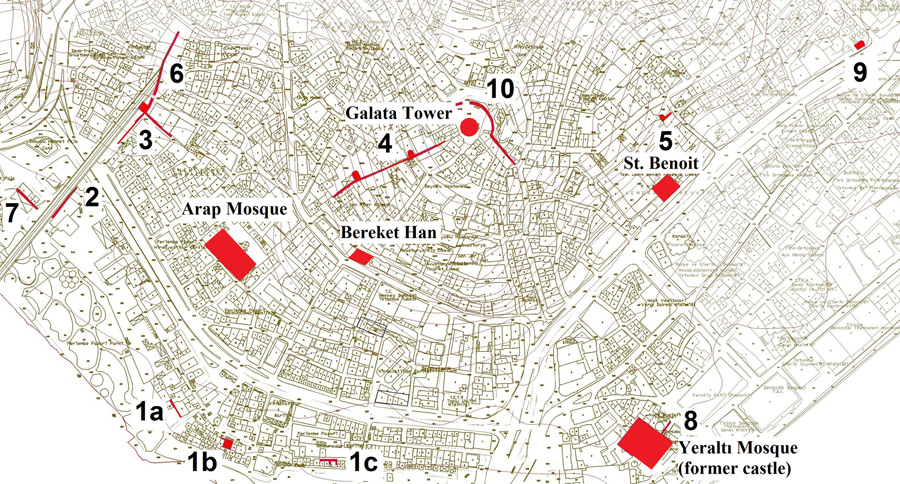

There are few Early Byzantine remnants in Galata also utilized during the Genoese period. The easternmost part of Arap Mosque (the former San Domenico church) and Yeraltı Mosque (the former Galata Castle) are examples of this issue. With regard to a comparative point of view, the supposed Genoese built heritage in the area follows the masonry tradition of the Late Byzantine period in the capital. However, some very significant stylistic, historical and epigraphic evidence, as well as the incapability of the Palaiologian Byzantine Empire to finance and execute such massive monumental constructions in this peripheral suburb, provide strong clues to the Genoese buildings. In any case, it must be stated that there is a clear synthesis between the western and eastern architectural traditions of that time as a result of this cultural encounter in Galata, as the Genoese brought neither construction materials nor workers from Genoa.

4- How well have the original Galata Genoese records survived and how accessible are they? Can we trace individual families and merchant houses in these records, trade disputes, building permits etc.?

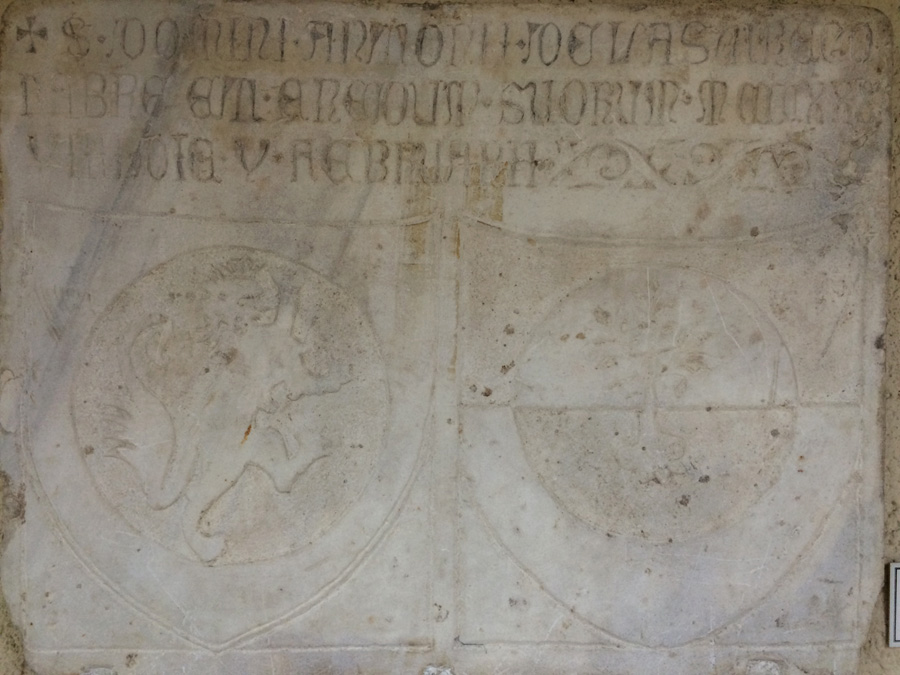

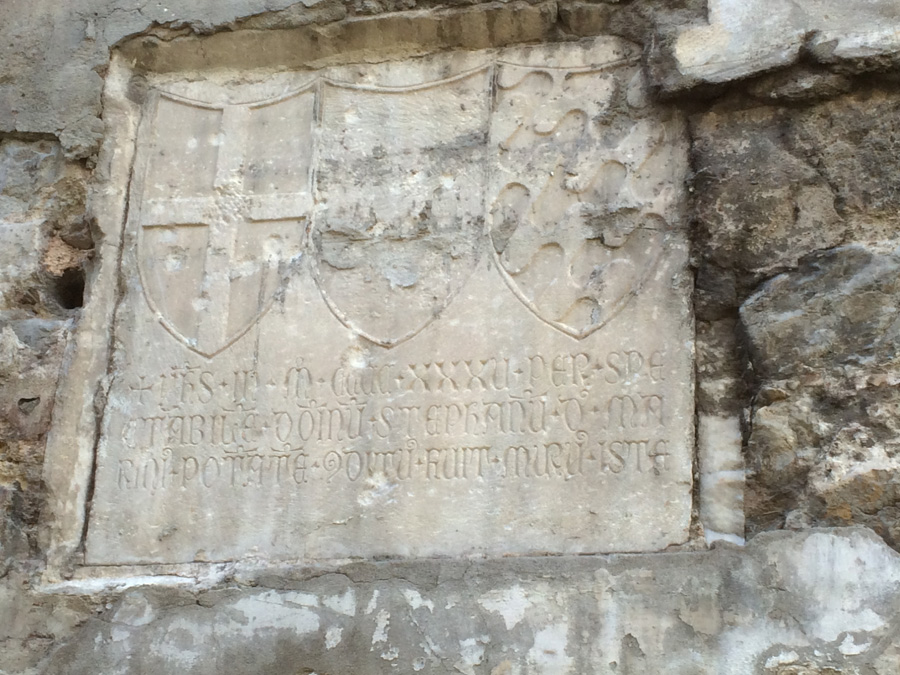

Very few records from the Genoese Galata have survived among the estimated whole archive from 1267 onwards. Other than a series of notary registries from some very separated periods also reaching to the late 15th century into the Ottoman rule there, the most significant documents could be given as the expenditures mentioned in Massaria registries of 1390-92, where precise details of various constructions in Galata were listed in a well organized manner. Almost all of the aforementioned documents are now located in the State Archive of Genoa and are accessible to everyone. A large group of them were also digitalized, therefore much easier to consult. In addition, a group of modern studies include transcribed versions of the aforementioned series, which is even more helpful to researchers for further interpretation. It is possible to trace many of the noble Genoese families in those documents where especially the notary registries contain valuable information. For instance, the coat of arms belonging to the noble family of De Merude is still located on a mural slab above Harip Gate in a remaining section of the Galata Walls. With the help of those notary documents, we can trace business activities of this family in Galata and precisely to which member of them the concerned coat of arms was representing, with regard to the supposed date of that slab.

5- The Genoese played no real part in the recapture of Constantinople from the Latins in 1261 nor were they very successful in defending the city from Venetian attacks during 1262-1264 and only in 1267 were allowed to return to their former quarter of Galata. Why did the Byzantines need them and provide them with such generous trade privileges?

After the Fourth Crusade, the Empire of Nicaea, being the main successor state of the Byzantine Empire after this catastrophe was largely a terrestrial entity in terms of military power, therefore very weak at seas. After the fluctuating diplomatic relations with the Genoese between 1262-1264, the recovered Byzantines even tried to reconcile with the Venetians through a suggested agreement in spite of their major role during the Latin domination in Constantinople. However, that treaty with many promised concessions was rejected by the Venetians in 1265. The second agreement with the Genoese was cemented through the reapproved Treaty of Nymphaeum (1261) in 1275 but within this negotiation and normalization process, the Genoese already found the chance of settling in Galata in 1267. All of these concessions were a kind of last resort for the Byzantines in order to have a naval shield. Without such an ally, the Byzantines would be even more vulnerable in case of a naval attack from any belligerent and might have faced immediate and irrecoverable losses once they have miraculously restored Constantinople. All in all, the Byzantines needed to give many concessions with the hope of receiving a bit.

6- The Genoese expanded their initial (1320-30s) quarter and secured it with walls both legally and illegally and this clearly shows that the Byzantines were powerless in imposing their full authority. Or is this an over-simplification?

It is true that the Byzantines were not strong enough to dictate strict rules to the Genoese after a while but on the other side, the Genoese simply tried to protect their colony and to expand its commercial capacity instead of terrestrial conquests to have a larger colony by land. In any case, whatever the true motivation behind the Genoese expansions, the Byzantines were capable to prevent this process for the final time in 1336 and then they lost the authority against the Genoese in Galata with a mostly a self-ordained manner. This decline was also symbolized with the disappearance of the Byzantine coat of arms on the Genoese mural slabs, which appeared together with the earliest examples with the last recorded one was from 1349.

7- What are the principal Genoese built buildings standing today and which do you think have been badly restored or are in urgent need of restoration?

The main Genoese period buildings standing today could be given as the diverse remnants of Galata Walls, the Arap Mosque and Bereket Han, being the former communal palace. Almost all parts of Galata Walls and especially Bereket Han are in an urgent need of conservation interventions due to long standing neglect and damages. Arap Mosque is in a good condition but it was inappropriately restored between 2010-2012, whereby the rich identity of the building was covered. As not all the remaining parts of the Galata Walls are under legal protection, a new listing process is necessary in the first place instead of a hasty restoration. In addition, there are some more minor remnants from the Genoese period but the ones mentioned above are undoubtedly the most characteristic ones of the former colony, therefore having a priority in this case.

8- How diverse was the population of Genoese Galata during its later period? Did the colony function like an autonomous state within the Byzantine Empire or was its first loyalty to Genoa?

The most detailed and earliest survey for the demographics of Galata in general was the Ottoman tax survey of 1455 which provides valuable information about the colony during its final years. Apart from the Muslim community which started to settle in following 1453, the demographics of Galata was already diverse: Jews, Greeks, Armenians and of course predominantly a Genoese Latin population... As there were members of various Roman Catholic sects like the Dominicans, Franciscans and Benedictines in Galata, the ethnic backgrounds of those people could also be different. The colony was subjected to Genoa in general terms but during some affairs with the Byzantines, there were some examples where the colony was having the chance of acting like an autonomous state. For example, a letter from Genoa dated 1317 warned Galata to obey the Byzantine regulations but it did not happen all the time and the Genoese inhabitants there broke the rules by expanding their territories especially through to the north, until 1348.

9- There is a whole collection of ‘Genoese castles’ situated in coastal locations in Turkey and beyond, such as Crimea. Do we know just how Genoese these were as there is clearly confusion on attribution. Were outposts such as Amasra on the Black Sea administratively controlled by Galata during that period? Was transfer of these castles to the Ottomans always agreed in peaceful terms as clearly the Genoese were in no position to challenge the growing might of the Ottomans during the 15-16th centuries?

Most of the attribution of the ‘Genoese’ castles all along the Anatolian coasts are largely based on popular folk traditions. Few of them were backed by inter-disciplinary approaches like primary historical resources and detailed onsite surveys. Thus, it is necessary to have a sceptical point of view to almost all of those castles. There was a hierarchical order between Genoa and its colonies of different sizes. For instance, Samastri (Amasra) was initially subjected to Caffa (Feodosia) but then connected to Pera (Galata) during its last years, where Pera was under the direct rule of Genoa, as a colony of it. The Genoese mostly preferred to negotiate and surrender in front of the enlarging Ottoman threat. By doing so, and due to being a pragmatic nation as previously mentioned, they have most probably intended to protect their commercial dominance by surrendering full independence in their various colonies.

10- There has been ‘heavy’ restorations of former Genoese castles such as at Şile (2015) and Hisarönü / Filyos Castle (2013). In your view are these necessary or could they be doing more damage than good in some cases?

The so called ‘Genoese’ castles of Şile and Filyos are both renowned in this way. Actually their restorations do have a scientific base but the concept of ‘restoration’ is in a huge evolution nowadays and the rather classical approaches were often criticized by some other schools of thoughts, which was also agreed by the wider society to some extent. This latter approach favours consolidation instead of a full restoration through securing the heritage from sustaining further damage. Accordingly, it is natural to expected that those recent restorations of Şile and Filyos castles created a huge controversy. In this case, it can be argued that the biggest damage was done to the identity of those monuments by giving this heavily altered impression, which was perceived by many people.

11- Do we know the population flows of Genoese post the capture of Galata by the Ottoman Turks in 1453? Was there net emigration of this community or did merchants still arrive as ‘Levantines’?

Some Genoese archival documents demonstrate that a certain number of the Genoese population of Galata emigrated to Chios (another famous Genoese colony) as well as Genoa despite the promise of Mehmed II (also known as ‘the Conqueror’) to protect their lives and commodities through the imperial edict dated 1 June 1453. Then, it was also announced that whoever fled would have their properties back in case of returning within 40 days, otherwise they were going to be expropriated. However, statements of the last podestà (chief executive) of Galata, Angelo Giovanni Lomellino written in a letter to his brother and dated later in the year of the Ottoman takeover did not depict a very bright situation for the former colony, which could be the reason behind the aforementioned departures. Yet the Ottoman tax survey of 1455 revealed the area contained a significant Latin population, it is clear that a certain number of the former colonists remained in Galata and most probably formed the ancestral roots of the Levantine minority of the modern Istanbul.

12- Through the Tentative List of UNESCO termed ‘Trading Posts and Fortifications on Genoese Trade Routes from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea’ which covers seven fortifications within the country (UNESCO, 2013) does not includes Enez Castle despite its strong Genoese (Gattilusio) identity, yet castles with relatively vague Genoese identities and usages like Yoros, Akçakoca and Çandarlı castles were included that even their Genoese period names are unclear. Moreover, the castles of Güzelhisar (Trabzon) and Çeşme were excluded despite their commercial importance during the related periods by the Genoese and also significant architecture, which cannot be counted after the aforementioned ones in terms of priority. Do you think this programme didn’t consult historians and archaeologists sufficiently and by excluding Galata Walls etc. difficult decisions such as demolition of later alterations were done for political expediency?

Indeed, it is almost certain that the committee responsible of the submission of that tentative listing proposal as well as the assessment commission did not consult to experts of the related subject from other disciplines. Otherwise, there would certainly be a different and actually a more accurate selection for that tentative listing. The inappropriateness of this selection is not negotiable. Superficial efforts in order to build a ‘Genoese’ identity for Akçakoca Castle were especially a pity in such a prestigious candidateship. The identity of Yoros and Çandarlı castles remain very complex and multifaceted when compared with the ones of Çeşme and Enez. Secondly, in my opinion, there is a selective understanding of heritage conservation in terms of being profitable in the long term; in which the remnants of Galata Walls were mostly considered problematic for the government officials rather than helpful, when considering the rapid urban evolution of Galata nowadays. Hence, the rather slowed down and mostly insufficient conservation measures for the related heritage were the possibly results of this selective point of view. Nevertheless, for political correctness, minimum measures were still taken such as listing procedures, removal of modern additions and official documentation available to everyone.

13- Clearly state and municipal authorities have paid little attention the Genoese Galata heritage and most recently one of the few remaining land wall sections was damaged by the M2 metro-line and the widening of the nearby Harib Gate which was unnecessary as it is no longer for vehicular access. Do you think stronger legislation is the answer? Is the Council for Monuments not doing its job properly, perhaps prioritising monuments it considers more ‘Ottoman Turkish’, or is ownership also an issue?

Absolutely. Nevertheless, the legislation is already strong enough but its implementation is mostly insufficient, therefore this problem now reaches a different address. Complex ownership statuses are an issue preventing quick solutions in Galata, as walls were formerly sold through auctioning either by building or by plot after massive demolitions starting from 1864. Yet, a limited budget for expropriation also prevents the authority from further action, when also considering prioritized monuments. Actually having an Ottoman Turkish identity is not truly necessary in this case, as in Istanbul we see numerous monuments of any kind in a neglected and ruined state despite their identity. Especially hammams, fountains and small mosques ruined long ago come first in this case. I think it is also a matter of profit and propaganda, therefore monuments which lack of this potential are likely to be eliminated and certainly under greater risk when in the face of a mega project.

14- The Arab Mosque (former San Domenico Church) still has an information panel in Turkish and English giving an incorrect history of the building claiming it to be built by besieging Arabs (Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik) and it has covered its rare frescoes in plaster post the 1999 earthquake that revealed parts of it. Do you think the policy of deliberate misinformation is to allow a free-hand in future alteration and preventing criticism of insensitive architectural alterations of the past? Do you think a compromise can be reached in the future?

I think authorities have been afraid of Arap Mosque being designated a second Ayasofya (St Sophia) because of its unique heritage value coming from the rich architectural history and priceless frescoes where the majority are hidden behind the brick cover above the former belfry. The building also has a strong contemporary Islamic identity based on a false folk tradition, therefore the possibility of it being converted into a museum would probably be an undesired situation by the state and it would create another huge controversy as well. Nowadays, it is possible to detect three series of information panels on the building where the written knowledge slowly evolves from very inaccurate to rather accurate, which is a kind of a tragi-comic summary of the situation. Nevertheless, the mosque identity of this former church is already a fact since its conversion in the late 15th century and certainly very valuable without the need of any legend.

15- Which do you think are the most significant finds of your research concerning the slabs and other elements of Galata’s past?

I consider the most significant discovery of my PhD research to be the precise continuation of the sacred space through the Byzantine period of Hagioi Anargyroi and Hagios Nikolaos, the Genoese period of Sant’Anna and San Francesco, and the Ottoman period of Yeni Mosque, where San Sebastiano and Bereketzade Medresesi Mosque are also an example to this issue. This discovery also proved that the characteristic grid urban layout of Galata certainly goes back before the start of the Genoese period there.

16- What are you researching currently?

As a part of my postdoctoral fellowship, I still continue my research on Galata. Other than new interpretations about the spatial enlargement of the colony, I have also discovered at least five parts of Galata Walls still remaining and not documented before. The Genoese presence in the North Aegean is another research subject of mine nowadays.

Interview conducted by Craig Encer

Biography

Born in 1990 Dr. Hasan Sercan Sağlam completed his BSc on Urban and Regional Planning at the Istanbul Technical University (2007-2011). He did his MA on Conservation and Regeneration in the University of Sheffield (2012-2013). He received his PhD degree in Politecnico di Milano (2014-2018) on Preservation of the Architectural Heritage.

Bibliography

Belgrano, L. T., (1877). Documenti riguardanti la colonia Genovese di Pera (“Prima serie di documenti riguardanti la colonia Genovese di Pera”, pp. 99-417, “Seconda serie di documenti riguardanti la colonia di Pera”, pp. 932-1003), Atti della Società Ligure di Storia Patria (Vol. XIII, 1877-1884), Genoa.

Eyice, S., (1969). Galata ve Kulesi - Galata and Its Tower, Türkiye Turing ve Otomobil Kurumu, Istanbul.

Hasluck (1905). Dr. Covel's Notes on Galata, The Annual of the British School at Athens (Vol. 11, 1904/1905, pp. 50-62), British School at Athens, Athens.

Palazzo, B., (1946). L’Arap Djami ou Eglise Saint Paul à Galata, Hachette, Istanbul.

Sağlam, H. S., (2018). Urban Palimpsest at Galata & An Architectural Inventory Study for the Genoese Colonial Territories in Asia Minor, Unpublished PhD Thesis, Politecnico di Milano, Milan.

Photo showing the damaging proximity of the M2 metro-line crossing the Golden Horn, emerging from a tunnel that pierced the Galata walls, built between 2009-2014.

The enlarged and damaged Harip Gate by the metro bridge whose frontage is now used as a car park.

The altered bell tower of the former San Domenico Church / Arab Mosque.

The altered interior of the former San Domenico Church / Arab Mosque with no frescoes visible.

The neglected Bereket Han (former Palazzo Comunale) in Galata.

The neglected frontage of Saint Pierre Han in Galata.

The coat of arms of Andre Chenier who was born in 1762 in the former house before Saint Pierre Han was built on the same plot by the French.

The French royal coat of arms of fleur-de-lys on the exterior wall of the same han.

A remaining section of the old Genoese walls near the Golden Horn.

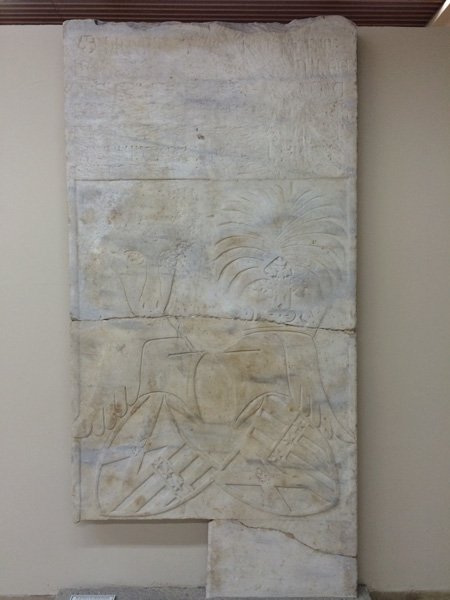

Another section of remaining Genoese walls displaying on the right with a slab with the coat of arms of Genoa and Podestà Stefano De Marini and dated 1435 - detail below:

A fragment of a tombstone with the French coat of arms now part of the flooring within Arap Mosque.