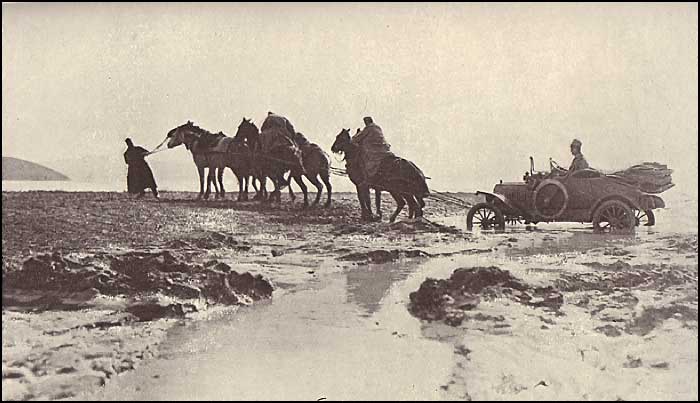

Macedonian mud: Serbian Artillery horses rescuing a Ford car.

Segment:

Chapter XVI.

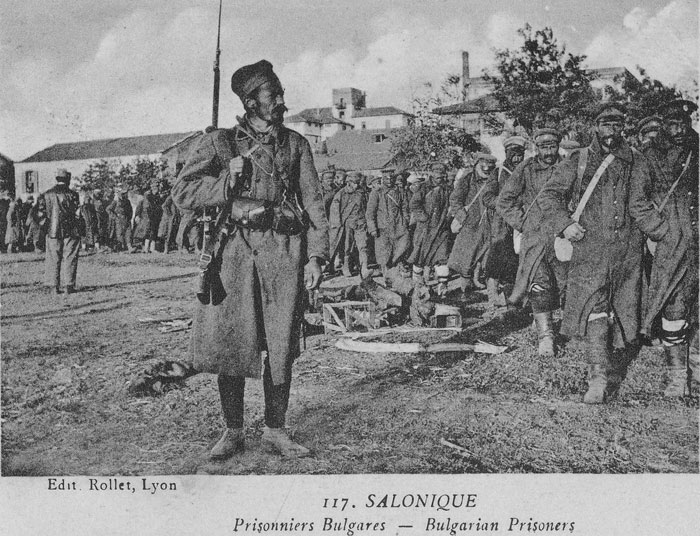

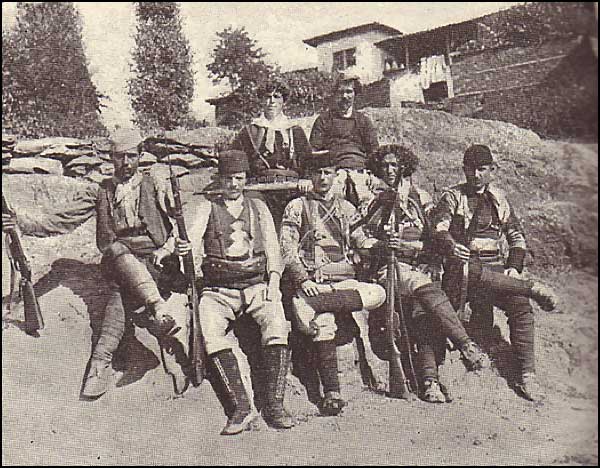

The Allied Operations.Though during the long three-years campaign in the Balkans there were many periods of enforced comparative inactivity during which only the regular growling of the artillery and the work of the patrols and the Allied aviators kept up the offensive spirit, there was far more fighting in the aggregate than most people in the outside world realised, and amongst them the various Allies—Serbians, French, British, Italians, even Russians, and, finally, the Greeks—laid down many thousands of lives on the barren mountains that mark the frontiers of Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria.

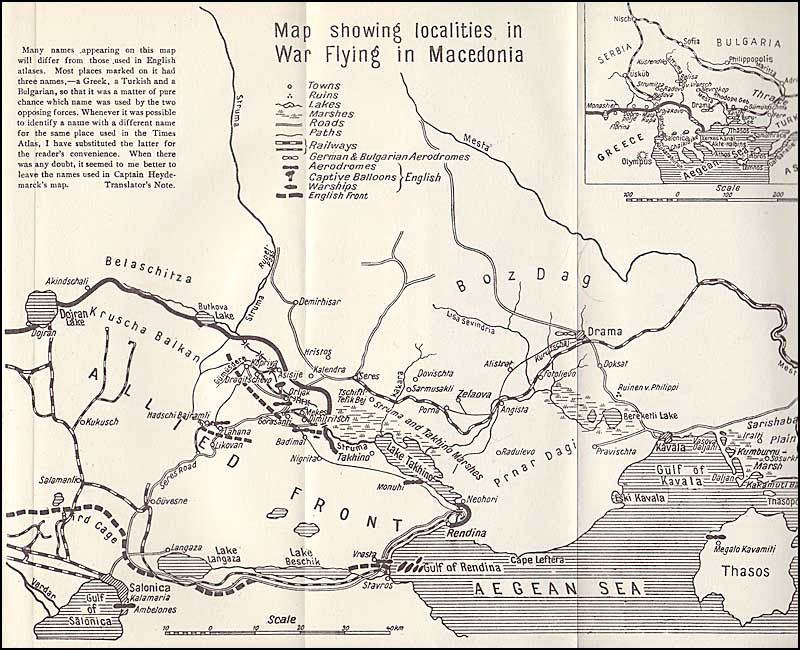

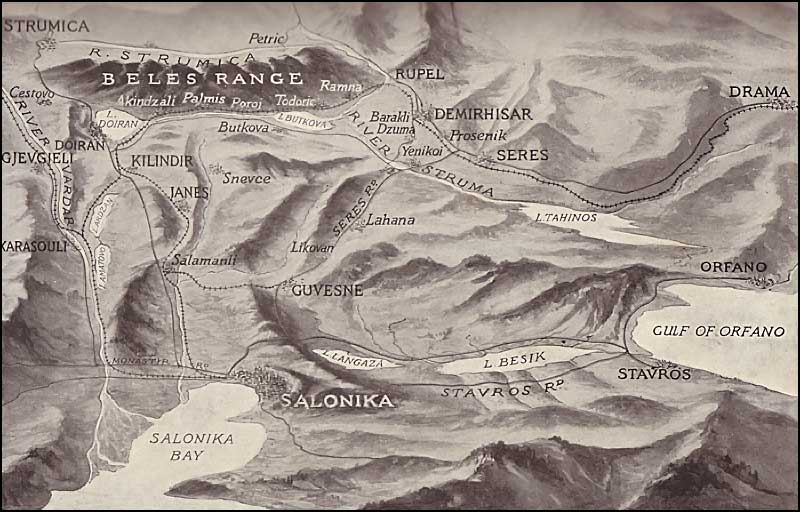

The Allied move out of the “Birdcage” in the spring and early summer months of 1916 to take up positions along the Greek frontier where the enemy—Bulgars, Germans, Austrians and Turks—had now entrenched themselves on most formidable positions, was followed by a long period during which change, re-arrangement, marching and counter-marching seemed to go on interminably. This was due to various causes; to “bluff” on both sides; to a proposed Allied Offensive along the Vardar, which had to be abandoned because the Bulgars got in first with their own attack on the left of the Allied line, against the Serbs; and also because of the fact that at first, owing to a number of reasons, British and French Divisions were mixed up in rather higgledy-piggledy fashion. The troops, who knew nothing of any of the reasons dictating these changes, found themselves committed to a good deal of hard and exasperating marching and counter-marching in exhausting heat, which seemed to lead to nothing in particular. Then the Italians who in September took up a twenty-five mile line on the Krusha-Balkan sector, between Lake Doiran and the Struma Valley, came as another dividing wedge between the two wings of the British front. It was not until towards the end of 1916 that the British finally settled down on the line running from the Vardar to Doiran, round the elbow made by the Krusha-Balkan range and so down the long Struma Valley to the sea—a distance of about ninety miles. This very extended front was held for two and a half years. Along its whole length we were dominated by enemy positions which were always markedly superior in strength—and height—and as a rule immensely superior. It was a crazy front, like the whole of the Balkan front, and zig-zagged up and down steep hills, in and out of ravines, ran along the tops of high ridges and finally brought us up on the Struma with its odd mixture of open and position warfare. To hold this very long front, always against superior forces, we had as a maximum four Divisions, much weakened by sickness and casualties. The 10th Division, after its gallantry and hardships in the retreat down from the Bulgarian frontier in 1915, took part in some stiff and successful fighting in the Struma Valley in 1916, and went to Palestine in September, 1917, there to win fresh laurels. The 60th Division, which only arrived in the Balkans in December, 1916, also went to Palestine in June, 1917, and saw comparatively little service in the Balkans, although it was to see plenty under General Allenby later on and to play a big part in his victories. At about the same time the 7th and 8th Mounted Brigades also went to Palestine . . .

|