The Interviewees

Interview with Reem Haddad - July 2023

1- This book project started with the discovery of boxes left over from Smyrna (20/25 boxes originally) that you found after a great search of 2 or 3 boxes. What exactly was in these boxes that you were able to rescue in the nick of time? Do they include group photos of teachers and students, internal correspondence, student name listings, account breakdowns, sporting achievements etc.?

The first three boxes I discovered contained numerous documents and letters from our time in Smyrna. I didn’t dare to open them all because some were so brittle. Some of them were speeches. There were also dozens of brochures dating back to the 1890s that showed the school’s various names and explained the latest curriculum. Most important were the dozens of photographs, many of which were in good condition, that showed us what life was like at IC in Smyrna. What I did not mention in the presentation was that I found another box later on in the basement of another building. No pictures, but it contained the original flag of IC in Smyrna.

2- After interviewing the grandson of the first founder of the International College of Smyrna you were able to track down the diary of Alexander MacLachlan at the American University of Beirut archives and discovered it ‘untouched’. Could there be other gems in this or other Lebanon based archives where presumably other pressing concerns over decades may have discouraged the work of researchers?

I don’t know for sure, of course, but it is highly likely that there are indeed more gems like the MacLachlan diary. I can now think of several archives: the Near School of Theology (NEST). This has a wealth of publications from missionaries and, incidentally, is where I found some Turkish (translated) newspapers harassing IC in Smyrna. There are also the American University of Beirut, Lebanese American University, and Jesuit University archives. There must be more, but these are the top libraries in the country.

3- International College was one of a network of Protestant Schools established by Boston based missionaries active across the area of the Ottoman Empire. Do we know how they went about seeking permission from the various Sultans for these schools and was one of the conditions not to educate and therefore not influence the Moslem populations? Do we know if these institutions were facing an uphill struggle to prove themselves against the already established France backed Catholic schools, so they paid great attention at providing a high quality education to encourage parents of the Christian minorities to choose them instead?

Capitulations allowed Levantines to attend separate schools in the Ottoman Empire. Until the Young Turk revolution in 1908, Moslems were not permitted to send their children to these foreign schools. However, some Turks could send their children to IC before that. Although the Karakol (police station) was just across the street, Turkish students could enter IC quietly through the back door. One student even fooled MacLachlan himself by taking on an Armenian surname.

IC had little competition from the French schools in Smyrna and was friendly with them. The liberal curriculum vastly differed from the French, Catholic, or Greek Orthodox schools. The school systems were very different, and it was up to parents to decide which system to put their children through. IC attracted many students because it also provided college-level courses and numerous extracurricular activities that other schools did not. Because the standard was so high, universities waived entrance exams for IC students who applied. Another draw was that IC was Smyrna’s first institution to have electricity. Except for the stressful times during the war, the school had to turn students away due to a lack of space.

4- To what extent were you able to obtain information and images from alumni of International College?

The pictures in the book from Smyrna were all taken from the boxes. I doubt any alumni are still alive today. But the Beirut photos came from other boxes I discovered from the 1950s and 1960s. I discovered a large number of unprocessed negatives, so I didn’t need to ask the alumni for any more photos.

5- 18 British and Indian WWI prisoners who were housed humanely in the campus of the International College of Smyrna died there and are buried there. Are their graves still visible and do we know if the Commonwealth Graves Commission is responsible for their upkeep?

I believe that the graves are still there. The school is now the headquarters of the Allied Land Command (NATO). I am not sure if anyone is looking after the graves, though.

6- Did the International College of Smyrna also have an agricultural arm so was it also a school for that sector or was that side more like a market garden to provide food for their own kitchen?

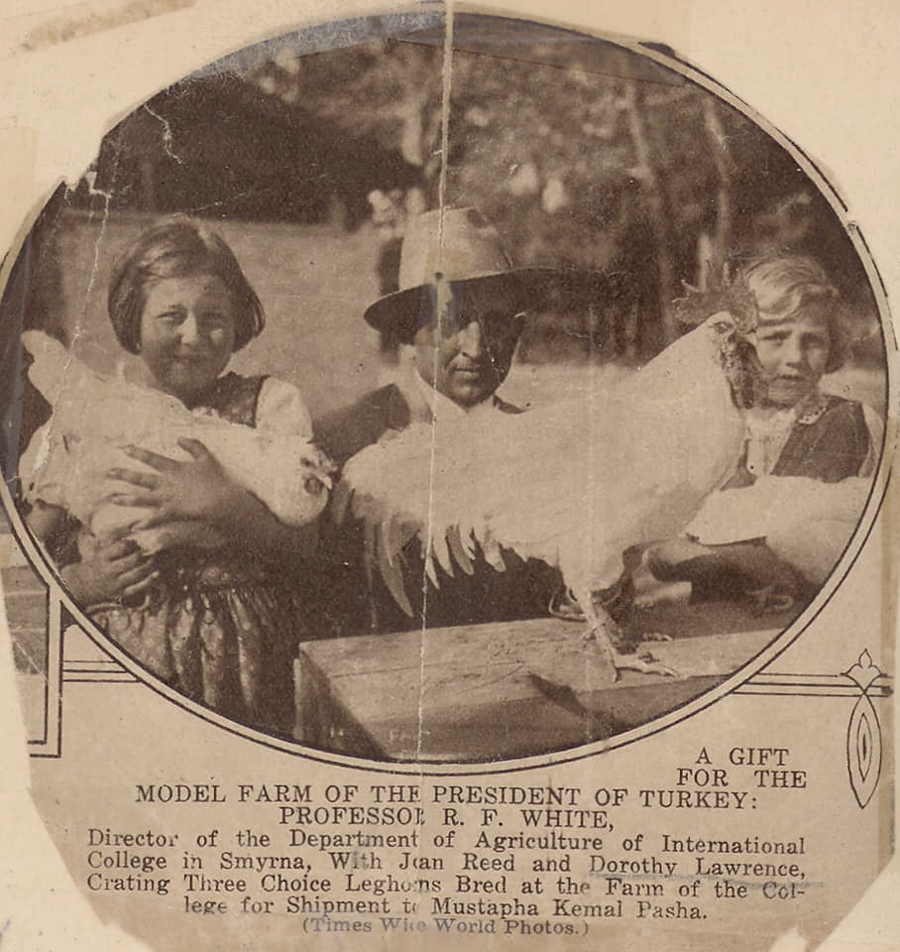

Rev. Alexander MacLachlan comes from a farming community in Canada, so he loved farming and thought that all students should learn farming – whether they become farmers or not. It was always his dream to turn some land near IC into farms. He imported dairy stock and poultry and Holstein cows. He developed a department that taught dairy, poultry, and bee farming as well as the traditional growing of fruits and vegetables.

A picture in one of the boxes shows students selling dairy products produced on the farm. There were also some pictures of the cows and a plow. So farming must have been very active. I assumed they supplemented the school’s food supply.

7- Did the International College of Smyrna provide refuge to minorities in the period of the Smyrna Fire and were there troubles with authorities because of that sanctuary it provided?

Every day, thousands of Greek and Armenian refugees arrived in Smyrna. IC accepted 1500 refugees. Except for those armed, anyone seeking refuge was taken in. Women and children were assigned sleeping spaces inside the buildings, while men and boys were assigned places outside, protected by the campus’s high south wall. American soldiers guarded the gates. During the ordeal, no refugees on campus were harmed. Most of the refugees, including Greek and Armenian IC students, were safely evacuated from the city.

Turkish authorities arrived at IC and separated the refugees into two groups: boys under the age of 18 and men over the age of 18. The men were allowed to stay at IC until late October before being taken as POWs. IC teachers, however, appealed strongly on their behalf, and they were finally released and sent to Greece.

8- The International College of Smyrna school curriculum had to change multiple times because of the massive changes happening around them such as when the Turkish Republic was established in 1925 and all education, excluding English language, had to be in Turkish as well as other restrictions such as no-religion. This clearly went against the original ethos of the school which was established along liberal protestant values so is it surprising for you that the professors agreed on these imposed changes and elected not to leave?

Despite the changes brought about by the new Republic in Turkey, IC remained convinced that it still had a role in the country and continued introducing new programs to the school. They were in denial about the potential impact these changes would have on their way of life. MacLachlan always enjoyed a great relationship with the Turkish authorities. He spoke Turkish fluently but did not really comprehend the changes that would take over the country. I don’t think it ever occurred to the school’s administrators and teachers that they would be targeted. It took them a while to realize that things had changed and that they were no longer wanted. The board sent a commission in 1933-34 to study the situation and concluded that not only was IC not wanted, but its raison d’être – teaching liberal protestant values – was no longer being fulfilled. It could not have been easy for IC administrators and teachers to leave the campus after putting in so much work. I found a letter in one of the boxes from Cass Arthur Reed. It was his last letter to his faculty and staff: “I think we are all intellectually satisfied that our work here as a College, was finished. With no apologies and no regrets for the years that have gone, we can all look forward to the next step in confidence and hope. We cannot keep as closely in touch as we could wish, but our paths will cross again from time to time and perhaps in a work together, we shall find a fuller life than we have ever known in the good days at Paradise.

Ever sincerely yours,

Cass Arthur Reed”

9- After the International College made its move to Beirut again it was not easy going and again and again it was left with no building it could call its secure base. Are you surprised how resilient its staff have been over the decades, including the civil war of Lebanon, that it continues till today? Did IC ever consider during the civil war moving to another country?

Lebanese people, in general, are very resilient. This was repeatedly demonstrated during the country’s civil war and subsequent political crises. The school survived and continues to exist because its mission is much more than an excellent curriculum. The secret to IC’s success is the same as it was in Izmir: a liberal education that promotes democratic values and freedom of thought and speech. This was a first in the Arab world. Until the start of the civil war in 1975, Students came from all over the Arab and African regions, drawn by this new way of thinking and teaching. These same students returned to their homes as community leaders. As a result, IC’s influence was felt throughout the region.

IC’s board considered moving the school to another country at one point during the war. However, there was a huge outcry. IC and Beirut had fused. No one could imagine the city without IC. Such was its importance in the country. Despite battles and shootings outside the campus, teachers and staff refused to leave the school and continued to teach. There was an unspoken feeling that if IC died, Beirut would die. Its mission must continue.

10- In 2012, 12 students and 3 administrators, included yourself, visited Izmir, invited by the American Collegiate Institute, of which you are a part, to the site of the former IC school there. How emotional and special was that occasion for both sides?

I still can’t describe our emotions as we walked onto our old campus. The reception we received was very touching. And when our IC students from Beirut took the stage, you could hear a pin drop. So many people were in tears, and I assumed they had all heard of IC because they seemed too young to have been alive at the time. It was also very moving to see IC’s history displayed on one of the buildings’ walls. Everything appeared to be exactly as it had been. Not much has changed according to the photographs I found in the box. Even a plaque commemorating the Kennedys’ contributions was still in place. It was a truly unforgettable experience.

11- Is there an alumni newsletter or website on which you can appeal for old records, photos or mementos? For example, the missing silver cup? What is the story behind that?

Shortly after the war ended, Rev. Alexander MacLachlan received a special thank-you gift from the British and Indian POWs he housed at IC during WWII: a sterling Silver Challenge Cup. The cup depicted the main building of the College on one side. Figures of wounded British and Indian officers were on either side of the pedestal base. The inscription on the cup said: “I WAS IN PRISON AND YE CAME UNTO ME”. It also said: “Presented to the International College at Paradise, Smyrna, by the British officers who, with their men, enjoyed the hospitality of the College and experienced the splendid charity of the college staff, during the last and happiest weeks of their long captivity in Turkey, through the years of the Great War 1914-1918”.

Until this day, I am searching for the cup. I know it was in the move from Smyrna to Beirut. But I don’t know what happened to it. I looked everywhere. We have a newsletter, social media, and a website. I have advertised the cup previously but sadly received no response. I think too many years have passed now. I had promised MacLachlan’s grandson, Howard Reed (son of Cass Arthur Reed), that I would look for it before he died. A promise is a promise, so I continue to look…

Interview conducted by Craig Encer

1903 dated pair of photographs of Collegiate Institute for Boys (active from 1897 replacing in status the American School for boys, opened in 1891) in the Basmane quarter which burned down in the Great Fire of Smyrna 1922. In 1903 the name of the school was changed again to the International College of Smyrna offering 8 years of education. This building was bought from the prominent Armenian family of Spartali in 1892, and served as the boys school until 1913 when it moved to the bigger campus at ‘Little Paradise’ (Kızılçullu) on the outskirts of the city.

In 1937 after much pressure the Turkish Government bought the Paradise Campus for 62.600 TL (~$49,700) and from then it served as a ‘Village Institute’ operating until 1952 when these nationwide rural educational institutes were closed because of the political leanings of the Adnan Menderes Government (who was ironically one of the alumni). The site then served and still serves from 1952 as the regional NATO Headquarters for Land Forces (motor pool) - additional photos: