The Interviewees

Interview avec Ozden Mercan - février 2022

1- You received your PhD from the European University Institute in 2017. What was the title please?

The title of my PhD was “In the Shadow of Rivalry and Intrigues: Diplomatic Relations of Genoa and Florence with the Ottoman Empire during the Sixteenth-Century.” My current project on Ottoman presence in Tuscany is to some extent connected to my PhD thesis. In fact it was while I was writing the section of my dissertation on the economic and political relations of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany with the Ottoman Empire that I conceived the idea of a project on the migration of merchants/artisans from the Ottoman Empire to Tuscany in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

2- You focus on the Ottoman merchant presence in Tuscany and when did this presence start, so shall we say there was a toleration of this presence and when and how did it end?

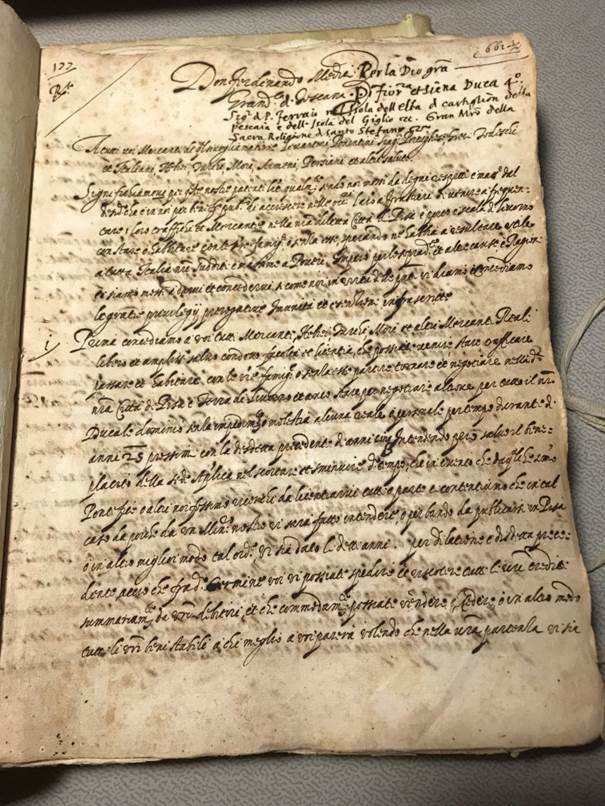

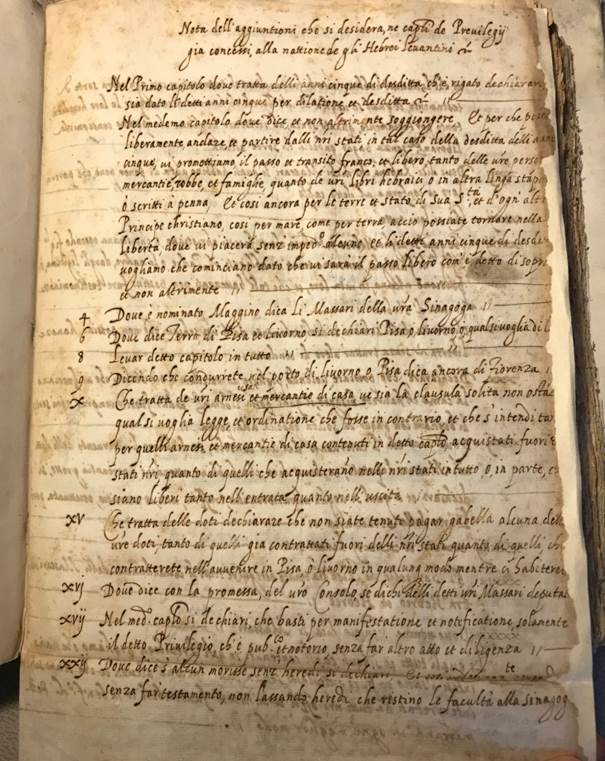

There were already attempts to attract merchants from the Ottoman Empire to come and trade in Tuscany during the time of Cosimo I (r. 1537-1574). In 1551 he granted residence permits, special privileges, and full protection to all merchants living in the Ottoman lands to come with their merchandise to trade in the city of Florence. In the 1560s and 1570s a number of Jewish merchants of Levantine and Ponentine (western-Portuguese and Spanish) origin settled in Tuscany thanks to these privileges; however, due to restrictions on Jews, even their expulsion and attempts to ghettoize them in Florence, Cosimo’s project did not have much success. It was during the time of Ferdinando I de’ Medici (r. 1587-1609) that some solid steps were taken to develop Livorno and Pisa. He released the edicts of 1591 and 1593, known also as the Livornine, which provided the legal framework for granting privileges and were regarded as important documents of tolerance since they assured the merchants that they could settle with their families in Pisa and Livorno without any impediment or molestation. These efforts seem to have attracted several Sephardic Jews from the Ottoman Empire to settle in Tuscan ports. In the seventeenth century there were also many Armenians from the Ottoman Empire conducting trade in Livorno. This port city maintained its importance as a significant trade entrepôt until Napoleon’s invasion in the late 18th century.

3- In 1534 the port of Ancona of the Papal States took the lead in opening its commerce to the Ottomans under the blessing of the Pope Paul III. Was there any resistance to this change of policy in terms of some cautioning against ‘trading with the enemy of Christiandom’?

In 1514, Ancona took the lead among the Italian cities, granting customs duty reductions to Greek merchants in the Ottoman Empire. Soon these privileges were extended to all Ottoman merchants. In 1534 Pope Paul III released a decree allowing all merchants from different nations and confessions to come with their families and commodities to trade in Ancona. Yet, Ancona lost its favored position in the 1560s due to the growing tension between the Ottoman administration and the papacy. The conflict between the two states was so great that in 1564 a sultanic decree stipulated that Ottoman merchants could trade only in Venice and Dubrovnik; they were not permitted to go to Ancona or anywhere else. Moreover, due to frequent papal interdicts, Ancona was subsequently no longer viewed as an attractive, welcoming city for Ottoman merchants. Thus, Venice became the main trade entrepôt for merchants from the Ottoman Empire during this period.

4- Clearly there was much rivalry between the various Italian states such as Venice and Florence and do you think the liberalising attitute in allowing privileges to foreign Jewish and Moslem traders was hastened by this desire to become the centre of trade with the Levant and do you think they also were open to the flow of ideas and innovations that this flow of people would allow?

By attracting foreign and local merchants and artisans to their cities by means of offering privileges, the Italian rulers sought to make their cities centers of international trade and exchange. In addition to reviving the economy and gaining prosperity, another important aim of these privileges was to import raw materials and to transfer the expertise necessary to develop certain industries more easily. Particularly in the case of Grand Duchy of Tuscany, it is possible to see that some merchants and artisans considered these privileges as an opportunity to further their own interests and they proposed to the grand duke and his officials that they would introduce new technologies such as production of new types of silk cloth and new techniques of dying cloth, glass production as well as leather production. Thus, these economic incentives enabled the Medici dukes to transfer technologies, expertise and skilled workers from everywhere, especially the Levant.

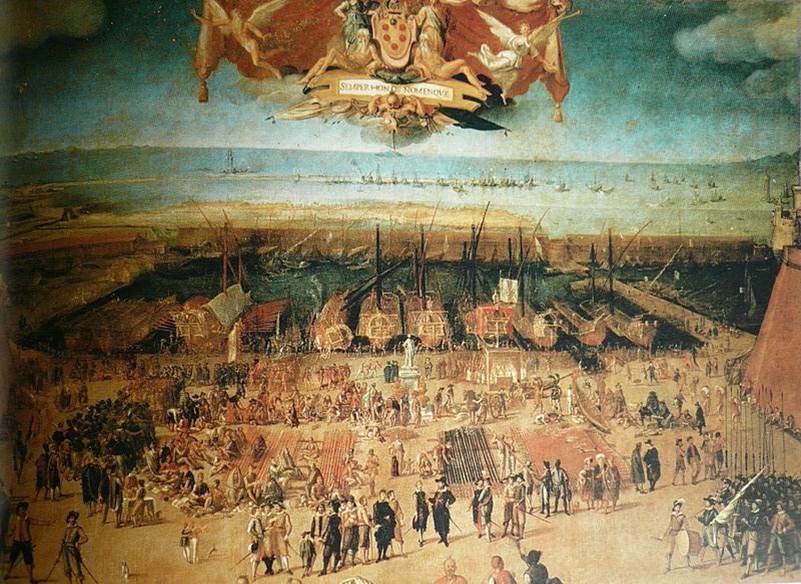

5- The Medici rulers of Tuscany invested over generations to developing Livorno both in terms of infrastructure and conditions yet they never restricted the activities the order of St Stefano tasked with defending the Tuscan domains against the Moslem raiders. Do you think the Medici project to rival Venice in the supremacy of this international trade was handicapped by its lack of experience and not being able to control the order of St Stefano?

Not really, it was a matter of choice for the grand duchy. The profit the grand duke gained from the activities of St Stefano was too good to give up. Moreover, this initiative was already a source of prestige and recognition for the grand duchy. On the other hand, it was highly desirable that Livorno become an international trade base and transit port that attracted merchants from everywhere. While the grand duchy was able to attract Sephardic Jewish merchants and other non-Muslim merchants from the Ottoman Empire to Tuscan ports thanks to extensive privileges, they also sold in Livorno the goods and people captured from the Ottoman Muslim ships by the galleys of St Stefano. It can be said that the Medici dukes straddled both projects since this served their interests best.

6- The decline in the textile industry through the 16th century seem to have again forced the hand of the Grand Duke of the Medici (Ferdinando) by publishing a new charter in 1591/93 of freedoms and priviliges for the foreign merchants in Pisa / Livorno. Clearly this was more successful than the earlier efforts as a significant number of Ottoman Jewish merchants starting settling in the region bringing with them new technologies and skills such as new methods of dying textiles and leather. Could we argue that by this stage Tuscany was able attain a similar position to Venice regarding its open-door policy leading to trade, leading to new innovations, which presumably was still a power to be reckoned with at this period?

Yes and Tuscany even attained a better position than Venice in attracting trade. While in Venice merchants from the Ottoman Empire were able to reside for a limited period of time in a segregated area and there were restrictions in terms of religious freedom, in the Tuscan free port Livorno they were offered better conditions for settlement such as tax benefits, freedom of trade, storage facilities, property rights and religious freedom. Moreover, due to its geographical location, Livorno became an important trade link between the Northern European markets and the Levant market, attracting merchants not only from the East but from the West as well.

7- Amongst the letters of safe conduct issued from Tuscan authorities to Ottoman merchants you have examined is an Armenian , Antonio Bogos from 1650. You referred to him as a very interesting figure. What was special about him?

Antonio Bogos, known also as Çelebi (1604-1674), settled permanently in Livorno in the mid-1650s and remained there until his death in 1674. He was the brother of a former Ottoman tax official, Hasan Agha, who had been executed and this was the reason for Bogos to flee the Ottoman Empire and came to Livorno. Bogos had already extensive mercantile networks when he was in Smyrna and during his stay in Livorno he maintained these networks and accumulated great wealth and status. He obtained Tuscan citizenship. One of the important aspects about him was that he acted as intermediary between the Medici officials and visiting Armenian and Ottoman Muslim merchants in the port. Through his economic and diplomatic connections, he conducted trade between Livorno, Smyrna, Tunis and Amsterdam. His Ottoman style palace is also noteworthy. My research on his life and activities in Livorno is still going on.

Vedute del Porto di Livorno, 18th c. - Museo dell’Opificio delle Pietre Dure, Florence

Livornina 1591

Livornina 1593

Galleys of the Order of St. Stephen, Livorno, 17th c. Museo di Santo Stefano, Pisa

Interview conducted by Craig Encer