The Interviewees

Interview with Ozan Ozavci - December 2021

1- In your previous research, you investigated the idea of liberty in the Middle East and the Caucasus, which resulted in the publication of your first book ‘Intellectual Origins of the Republic: Ahmet Ağaoğlu and the Genealogy of Liberalism in Turkey’ (Brill, 2015). Ağaoğlu is somewhat forgotten figure in the modern Turkish world but perhaps this is why you focussed on him. He introduced himself as a Persian in the essays, defended the Iranian historical presence and importance in the Islamic world and blamed the Turkic peoples for the decline of the Islamic civilization. Yet later he also began embracing his Turkish identity while playing an important role in the prevention of ethnic clashes between Armenians and Azeris. Do you think his later influence on Ataturk has been downplayed by the official historiography because of his views on liberalism and female emancipation went further than was comfortable for subsequent political leaders such as İnönü?

Yes, it’s true that I started my academic career as an intellectual historian in the 2000s. There was a very different political situation in Turkey back then. The new Erdoğan regime was looking to further democratise the country, establishing cordial relations with both the European Union and Middle Eastern neighbours. They were showing eagerness to recognise and settle the Kurdish question, while at once looking to fix the long-devastated economy. It was in that context that I became interested in the Turkish idea of liberty and political and economic liberalism, and wrote articles and my doctoral thesis (which became my first book) on late Ottoman and early republican Turkish liberal thought. I was curious about the problematic relationship between Kemalism and liberalism, and the allergy to diversity in Turkish political culture back then. I chose Ağaoğlu as the sole focus of my analysis in my book because of his unique position as a leading liberal figure in the early republican context.

Ağaoğlu was originally from the Russian Caucasus. Born into a rich, Shi’ite family, he indeed associated himself with different ethnic identities in different times and places. When he went to Paris for education in the late 1880s, he introduced himself as a Persian mainly for pragmatic and opportunist reasons. This was largely because his mentors were interested in Persian history. He found it fitting to use the fact that he was a Shi’ite (even though it’s doubtful he practiced religion by this point) and that he could speak Persian to his scholarly advantage. But it worked. He did manage to get himself invited to study under James Darmesteter, and to the famous salon meetings in Paris, where he met several prominent intellectuals. Even though this lasted only a few years, the idea that the development of the moral faculties of the individual was the capital problem of modern times (an idea that he borrowed from Ernest Renan) stayed with Ağaoğlu always. After he returned to the Caucasus in 1894, he became an activist intellectual, pursuing a double struggle, on the one hand, against the Tsarist state, which had turned oppressive in the 1880s and limited Russian Muslim political and cultural rights, and on the other hand, against the Islamic mullahs, who, Ağaoğlu believed, morally weakened the Russian Muslim community. Only after he fled from Russia and came to Istanbul in 1908, after the Young Turk revolution, we find that he explicitly embraced Turkish identity. By 1911-2, he emerged as a pioneer of Turkish nationalism and a member of the Committee of Union and Progress though he never sat at its central committee.

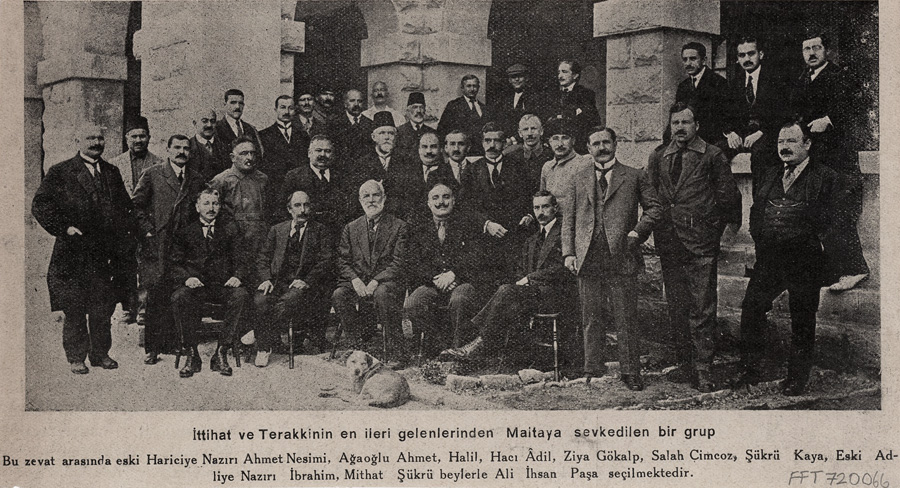

His Unionist-links and war-time propaganda was what prompted to his imprisonment in Malta after World War I. His nationalist propensities and personal connections (he was a close friend of Ziya Gökalp) was then what led him to receive invitation to Ankara after his release in 1921. He became the head of the Anatolian Agency, propagating for Mustafa Kemal’s cause. And for nearly a decade, he was among the few that sat at President Mustafa Kemal’s famous dinner meetings, discussing with him the future of the nascent republic. In the 1920s and 30s, the ruling party of Ataturk would call itself a liberal (in Turkish, liberal) party, and Ağaoğlu was particularly content with it. But this was a very nationalist liberalism, finding inspiration in French enlightenment thought with all its exclusionary undertones.

Ağaoğlu’s influence on Ataturk was arguably downplayed by the official historiography as the latter came to strip the term liberalism from Kemalist thought, disassociating the two, especially during the Cold War. Also, it’s true that there was a clear disliking between Ağaoğlu and İnönü, especially since Ağaoğlu criticised the rapid authoritarian turn under İnönü’s second Prime Ministry in the mid-1920s. Their hostility became even more evident during the short-lived Serbest Cumhuriyet Fırkası (Free Republican Party) experience in 1930, when Ağaoğlu joined the opposition party of Ali Fethi (Okyar) at the request of Ataturk. You can find traces of this disliking also in the writings of Ağaoğlu’s children, especially Süreyya Ağaoğlu, who became the first female lawyer in Turkey.

I think Ağaoğlu’s influence over the Kemalist regime’s future became very thin after the 1930 episode. He had to retreat from politics. He was not allowed to teach at university. And he did what many of the loyal opposition figures in Turkey did at the time. He greatly toned down his criticism to the regime, and focused more on his own intellectual activities, which included translation work and the organisation of salon meetings in his house every Monday evening. He invited prominent rightist and leftist figures from Peyami Safa to Nazim Hikmet to discuss contemporary political and philosophical issues of the time. The content of their discussions was published (I think after some self-censorship) in a journal called Kültür Haftası (The Culture Week) every week, as I discuss in my first book. As the term liberalism gained a pejorative connotation in Turkey during the Cold War, Ağaoğlu and his ideas, like many other liberals, received considerably less attention until the 2000s. This being said, his influence persisted through hundreds, maybe thousands, of students he taught at the at the law faculty in Ankara and Istanbul. These students became (Kemalist) bureaucrats and statesmen that ran the Turkish state for decades.

Venue of Ağaoğlu’s famous salon meetings in Tesvikiye, Istanbul (architect Sedad Hakkı Eldem), which was demolished around 1965.

Group photo of imprisoned Turkish nationalists in Malta after World War I.

2- Is the term ‘Great Power’ exclusively a label for Western nations, and can this ever be turned on its head, such as the Ottoman–Egyptian invasion of Mani in Southern Greece of 1826?

I think a short answer to this question would be a yes, the term Great Power was a label used largely for Western nations in the nineteenth century. It was made a legal category (as opposed to smaller powers of Europe) first with the Treaty of Chaumont and during the Vienna peace settlement in 1814-5. I think the idea arose during the talks among the leaders of the main European Powers, Austria, Britain, Prussia and Russia (later joined by France) at the Vienna apartment of the Austrian Chancellor Prince Klemens von Metternich. During the Congress of Vienna, the Powers wanted to involve the Ottoman Empire in the Final Act, guaranteeing the territorial integrity of Sultan Mahmud II’s European dominions. But it was not treated as an equal to the ‘Great Powers’. It was one reason as to why the Ottoman ministers rejected the proposal. Though I remember seeing in some correspondence of the time, especially in the writings of Friedrich von Gentz, the confidant of Metternich and the Secretary of the Congress, that the Ottoman Empire was also informally labelled as a great power. I believe it was merely an incidental practice.

3- You place the beginning of the Western imperialistic meddling in the Middle East with the French campaign in Egypt and Syria of 1798, ending in their defeat by Great Britain, allowing the latter to make a long-term foothold in the former Ottoman domain of Egypt. Clearly this was a vain-glorious affair of Napoleon imagining of ultimately joining the forces of Indian ruler Tipu Sultan and drive away the British from the Indian subcontinent and thus weaken the British Empire and make the Mediterranean into a ‘French lake’. Clearly this would antagonise the population of Egypt and the Ottoman Empire and thus destroy a long period of peace with the latter power. Was that consideration ‘brushed aside’ by the arrogance of Napoleon?

Foreign interventions, and especially western interventions in the Middle East did not begin in 1798. There were many other precedents that can be traced perhaps back to the first crusades. What makes 1798 of a novel nature is that it epitomised a new discursive practice, as I wrote in Dangerous Gifts, whereby the self-defined Great Powers of the time came to assume the right to supply security in the Middle East for the benefit of the locals, be it Muslim or Christian, or any other ethno-religious group. This discursive practice found inspiration in the enlightenment thought, in the belief that once acquired, truth can be taught to others, others can be civilised. Of course, there was a long list of political, strategic, financial, and economic reasons behind the French invasion of Egypt at the time. It goes beyond cutting the jugular vein of the British Empire by capturing its transportation and communication lines with India. But Napoleon and, as importantly, French Foreign Minister Charles Maurice Talleyrand considered or framed the invasion as a “grand service” to the Ottomans and the Egyptians, a service to both Sultan Selim III and the Egyptian population. They did expect that it would antagonise the population of the Ottoman Empire and Egypt, and to soften to blow, they released the Muslim prisoners in Malta, and Bonaparte was even styled as a Muslim leader after he landed in Egypt. Talleyrand planned a visit to Istanbul to persuade the Sultan that the real reason for the invasion was to eliminate the Mamluk beys who had menaced both the Ottoman rule and the French trade in the Levant for decades. They wanted to benefit from Selim III’s admiration for France.

But theirs was a hefty miscalculation. Yes, one can bluntly say that it stemmed from a hubristic arrogance, but a more elegant way of putting it would entail borrowing from Ann Kaplan that term, the ‘imperial gaze’. Bonaparte and Talleyrand gazed at the Levant but failed to look or see the local realities, emotions and complex religious and cultural dynamics. Especially the French pillaging after the invasion of Cairo and the brutal suppression of the Cairene uprising in October 1798 proved that the French hardly had popular support on the ground. The intervention was doomed to fail from the start. Even more ironic is that after the French fleet was destroyed by the British Admiral Nelson and British and Ottoman imperial armies arrived in Egypt, the French generals even looked to form an alliance with the former Mamluk rulers for whose elimination they had invaded Egypt in the first place.

Jean-Leon Gerome painting ‘General Bonaparte with his Military Staff in Egypt’, 1863.

Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, Napoleon’s chief diplomat, painting by François Gérard, 1808.

4- You draw many parallels with this Imperial intervention history with the more recent American invasion of Iraq post 9-11 for regime change and there were a few Arab intellectuals who welcomed this ‘gift’ from the West, like Fouad Ajami. Ajami published his first book, The Arab Predicament, which analysed what Ajami described as an intellectual and political crisis that swept the Arab world following its defeat by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War. Do you think the Arab crisis in identity following catastrophic defeats is a repeating pattern, perhaps going right back to the Mongol sack of Baghdad of 1258, so there is perhaps an enduring sense of victimhood when dealing with outsiders? Or do you think Western interventions post 1798 are of a different nature to the earlier humiliations as what the West wants is more than temporary bounty or is perceived as such?

I think it would be anachronistic to speak of a monolithic Arab world and patterns in their social psychology from the thirteenth century to present day. It’s not only because what’s at hand here is an immensely diverse group of people especially when we think of the Arab world stretching from Algeria to Yemen or Iraq. It’s also because I doubt there ever was a full-fledged ‘Arab identity’ at least before the late nineteenth century.

Even though in Dangerous Gifts I give great value to uncovering the local reception of western interventionism in the late 18th and 19th centuries and no longer discussing it or the Eastern Question from a purely west-centric lens, what I tell in the book is a very different story. As I said before, post-1798 interventions were truly of a different nature; they were indeed more than religious wars for the holy lands though many European writers of the time liked to frame the 19th c. interventions as ‘new crusades’ to galvanise public sentiments. The post-19th c. interventions looked to benefit from the alleged and arguable weakness of the Ottoman Empire in the Levant, and to establish new transimperial networks with both Arab and non-Arab, Christian and non-Christian populations of the Levant in an attempt to further the intervening power’s economic, political, strategic and eventually financial interests. The collective intervention of Austria, Britain, Russia, Prussia and the Ottoman Empire in Syria in 1840 can be viewed as a humiliation to Mehmed Ali Pașa of Egypt, whose forces were driven out Syria. France supported the cause of Mehmed Ali until the last minute and in the end the intervention proved to be a humiliation also for Paris. But, at the same time, it was a cause of jubilance for the Maronite peasants of Lebanon that revolted against the Egyptians with the material support of the Powers. From 1798 onward, the military, political, economic, and technological power gaps between the leading-edge European empires and Levantine polities like the Ottoman Empire and later Mehmed Ali’s Egypt became more and more clear to both European and Levantine actors. The Eastern Question became a speech act on its own right, a trope manipulated by the Great Powers to authorise their cycle of military interventions to different ends. But it was manipulated also by the Levantines, i.e. the inhabitants of the Ottoman world in the Eastern Mediterranean coasts, both the Ottoman imperial elites and subjects, whatever their ethno-religious origins were. The Levantines were not as passive as has usually been narrated in the literature. They looked to use Great Power involvement in the Levant to further their own interest and more often than not succeeded in this. Figures like Mustafa Resid Pașa, one of the architects of the Gülhane Edict, explicitly wrote how the 1840 intervention in Syria ought to take place, “not in the name of liberty, … but in the name of security”, and not by a single power as it would carry the risk of a permanent invasion, but collectively, with the involvement of more than one Great Power. He wanted to bind the intervention with international law, and it was another example of how 19th c. interventions differed from earlier accounts. The cycle of interventions in Greece, the wider Ottoman world during the Ottoman-Egyptian civil war in 1831-41, in Syria between 1840 and 1864 were all legally bound. They all ensued conventions that limited the size of the armies that would be involved in the intervention and the duration of interventions, and mostly ensured their multilateral nature. Even though this was not the case in the French invasion of Egypt in 1798, it provided the Powers and the Levantines with an important learning experience with respect to the global power gaps and imbalance as well as how international law could inform interventionism. Though I must underscore that while non-intervention in each other’s affairs became a principle among the Powers in Europe, international law even enabled imperial expansionism and colonialism outside Europe.

As for the Ottoman imperial subjects, observing the ever more apparent power differentials as of the late eighteenth century, they began to seek the aid of one or more Great Power against rival pashas or the draining rule of their Ottoman overlords, but along the way, their ties of friendship with each other were disrupted, and the magnitude of the conflicts among them were heightened by Great Power involvement, resulting in a security paradox: an ever increasing demand for security in the Middle East despite its allegedly increasing supply.

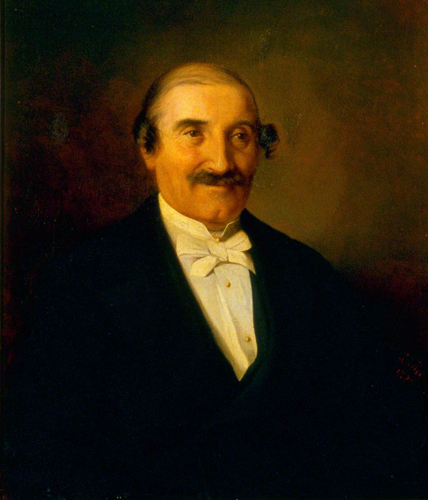

Mehmed Ali Pașa of Egypt, painting by David Wilkie, 1841.

5- Your book covers the period from 1798 to 1864, but also clearly making references to the more modern conflicts. Why did you choose 1864 as an end point?

Because I believe that the period between 1798 and 1864 was a unique learning curve, which resulted in the spontaneous configuration of a new culture of interventionism or a transimperial security culture, after decades of armed interventions, surrogate wars to sustain imperial interests, pacific blockades, and the introduction of Great-Power mediated administrative structures as well as many other recurring practices that constituted this culture. The experience amassed in this period served as a model or blueprint for generations of statesmen and diplomats. The semi-autonomous administrative model implemented in Mount Lebanon in 1864 inspired the administrative model introduced in Crete by 1869 through the mediation of Great Powers. Fast forward to the 1910s, when a civil war broke out between the Armenians and the Kurds in eastern Anatolia, the Powers again intervened, though diplomatically this time, and they again looked back to the Lebanese experience. Moreover, the integration of the Ottoman economy with global finance capitalism was made complete not with the 1838 Treaty of Baltalimani, as is usually argued in the literature. I try to show in the book how the commercial agreements signed between the Ottoman Sublime Porte and European powers as of the 1790s gained a new character from 1861 with the Treaty of Kanlica with France and other European powers. By late 1855-6, the Ottoman Empire became financially dependent on European banks and syndicates. The history of the financial colonisation of the Middle East began then, not in the post-World War II Middle East after the independence of various colonies, but with the financial turn of the Eastern Question. Through holistic perspective I argue that the aggregate of military, political, economic and financial interventionism constitutes the genealogy of our current culture of interventionism. If I may promote the book, it’s what makes Dangerous Gifts the first truly genealogical analyses of contemporary western interventionism in the region. As I argue in the epilogue of the book, we share this culture with our nineteenth-century forebears.

6- The ‘Eastern Question’ is a controversial and multi-layered issue surrounding the Great Powers jostling to fill in vacuums lefts by a shrinking Empire occupying and increasingly strategic region of the world. Were the intellectuals of the Ottoman realm conflicted on many levels between seeing the predatory approach of the foreign powers on their domains, yet also realising the weakness of the Ottoman system was partly a result of it not being inclusive enough (or perceived as such) for the various communities of the Levant. So were the seeds of dissent and civil war already there in that community diversity yet sense of alienation from the distant capital that was Constantinople? Did the Ottoman authorities try their best to bring representative governance to places like Mount Lebanon and provide them with a sense of autonomy to counter-act these rebellious tendencies?

Yes, the Eastern Question was truly a multi-layered or what I prefer to call an inter-sectoral process. Without looking into how domestic political, economic, financial, religious or cultural considerations informed diplomatic decision-making processes (and vice versa), we can have only a limited grasp of it. But I must remind you that the Eastern Question meant different things in different moments of the nineteenth- and twentieth centuries after the term was coined. The term itself was a discursive practice or a speech act that served as an enabling force for interventionism, enabling inter-imperial cooperation and competition, as well as expansionism and colonial control.

Yet none of this is to say that imperial foreign interventionism was, or has been, the sole cause of conflicts and civil wars in the Middle East. It would be a gross exaggeration to argue so. Egypt had already been in turmoil and suffering persistent civil wars before the French invasion. 1798 only heightened existing hostilities. The Ottoman elites had already been in dissidence when Mehmed Ali Pașa rose against Istanbul in 1831-2. The Russian intervention in 1833 made the situation even more complex as it engendered the involvement of the other powers, France supporting Cairo, and the rest Istanbul. As for the causes of civil war and sectarianism in Mount Lebanon, I argue in the book that sectarian violence preceded the 1840 intervention. In this respect, I differ with Usama Makdisi, who, in my view, is the most authoritative scholar on violence in the 19th century-Ottoman Lebanon. I admire Makdisi’s writing style and the analytical power of his arguments. In fact, when I began to work on interventionism, my plan was to write an in-depth historical analysis of the 1860 intervention in Mount Lebanon, drawing from his widely accepted argument that sectarian disaggregation was a post-1840 phenomenon, that came with modernity, and resulted from the reform process in the Ottoman Empire with the introduction of the Tanzimat era in 1839 and the Great Powers’ intervention in Syria in 1840, after both of which local people were categorised along sectarian lines. Sectarianism was then instrumentalised for political ends and institutionalised. But archival findings led me to a very different direction.

If we define sectarianism as Makdisi does, i.e. ‘deliberate mobilization of religious identities for political and social purposes’, then we see that it was already an important aspect of inter-elite as well as class struggles before the Tanzimat and before the 1840 intervention. Already in the 1820s, religious identities were mobilised during the clash between Maronite and Druze leaders. Religious slogans were shouted during the confrontation of Bashir II and Bashir Jumblatt in 1825. Mehmed Ali Pașa and the Grand Amir of Lebanon did scheme for ridding the mountain of the Druze leaders in 1831 before the Pașa’s campaign. Already in the mid-1830s, bureaucratic roles were allocated in the city council and the main court as per the sects of each major local population. Sectarianism had been in gestation for a longer period and sectarian violence burst out from the 1820s onwards due to a variety of factors. These include the Maronite clergy’s alliance with the peasants in their quest for a more egalitarian society in the global age of revolutions. They were inspired by revolutionary ideas as early as the 1800s-1810s. Feeling threatened by the growth of communal consciousness among the Maronites, the Druze leaders desired to rule at least the Druze districts. Add to this inter-class and longer-lasting intra-elite rivalries and land (and other economic) disputes. The reform process and Great Power interventionism surely contributed to it, too, but considering them as the enabling context in which violence erupted and sectarian disaggregation emerged and became a culture would be to give too much agency to the imperial actors and too little to the locals, to their ideas, ideals, emotions and expectations that predated 1839-40.

Having said all these, we should never lose sight of the fact that class and sectarian violence took place at the time still within an (Ottoman) imperial system. There had hardly ever been an Ottoman peace (Pax Ottomana). It was a fantasy. The imposition of political hierarchies and economic exploitation that came with empire tended to serve as destabilising factors.

7- How did Mehmet Ali Pasha of Egypt become so powerful with an army at one stage able to even threaten Constantinople? Did this Pasha’s expansionist moves under the guise of a civil war provide the perfect cover for the 4 powers (Russia, Austria, Britain and Prussia) allied to the Ottomans to free Mount Lebanon from Egyptian control in 1840, leading ironically to further chaos and instability?

It might be better to start answering this question with why Mehmed Ali Pașa strove to be so powerful. He became the governor of Cairo in 1805 during a complex, tri-partite civil war that broke out in 1801, in which he defied the Ottoman overlords. But then he managed to get himself appointed as governor and remained in power mainly thanks to the popular support of the Cairenes. In his books, Khaled Fahmy explains this extremely well. But even after Mehmed Ali came to power, he knew that Istanbul was uneasy with this situation and would look to replace and then destroy him at the first opportunity. He was appointed to different provinces of the empire more than once in the second half of the 1800s but he persevered to stay in Egypt. Also, the fact that the empire was in war with Russia (and for a short while with Britain) at the time, and that Bonaparte and Tsar Alexander I were making concrete plans to partition the sultan’s dominions weakened the hand of the Topkapi Palace against Mehmed Ali.

Mehmed Ali made use of the Napoleonic Wars in at least three ways. Politically, he managed to remain in power. Economically, by selling grains and other agricultural products to warring European Powers, he made immense profits, which he then used for building his own New Order army and eventually a strong navy. And finally, he built on reforms introduced under the French rule in 1798-1801 while after the war he recruited former-French officers (from Bonaparte’s disbanded armies) to help him reform his own army, navy and bureaucracy. And with his more advanced army, he wanted to expand and control especially Syria because he considered the Taurus Mountains a natural defence line to his dominions.

As for your second question, the European Powers were initially only indifferent to Mehmed Ali’s expansionism. They did not want to intervene in Ottoman domestic affairs or ‘the civil war of Islamism’, as one French agent wrote at the time, even when the Pașa’s men defeated the Ottoman imperial army in Konya in December 1832. But in 1833, after the Russian intervention, and the establishment of a Russian dominant influence over Istanbul the situation changed. It became a grave concern for Britain and France, and eventually Austria, to end this dominant influence.

In seven years’ time, especially after the Russophobe camp among the Ottoman ministers gained power, Russia decided to act jointly with the other Powers and the Ottoman Sublime Porte. They then collectively pressured Mehmed Ali to evacuate Syria. But Mehmed Ali resisted, seeing that France was still supporting his cause and expecting that the Powers would not go to war because of differences between Istanbul and Cairo. But France backtracked in the end. The other four Powers and the Sublime Porte used a Lebanese uprising taking place against Mehmed Ali in Mount Lebanon to break French resistance and then as a cover to intervene, which they duly did in September 1840. In November, Mehmed Ali’s forces evacuated Syria.

8- In the 1830s Sultan Mahmut II gambled with the Russians for their support to stop the Egyptian armies from capturing Constantinople and it worked as that panicked Britain which feared Russian controlling the vital straights. Do you think Mahmut II was far sighted in this outcome or was he desperate and prepared to sign up with almost anybody to save his skin?

He was desperate. When Britain turned down his offer of an alliance against Mehmed Ali, especially with the insinuations of Husrev Pașa, an age-old personal enemy of Mehmed Ali, and the sultan’s serasker, the Ottoman equivalent of Minister of War, Mahmud II agreed the Russian offer of an alliance. But he did so reluctantly, since Russia was a traditional enemy that had embarrassed his military many times, the last being only 4-5 years earlier. It was more to save face. But shortly after he signed a defensive alliance treaty with Russia in the summer of 1833, he looked to emancipate his ministers from Russian dominant influence. For this, more than anyone, his young diplomat Mustafa Resid played a pivotal role.

9- In 1839 Mustafa Reshid Pasha following yet another Ottoman military defeat against the Egyptian forces, this time in Syria, invited the great powers as an alliance to intervene, which was perhaps another gamble, in the name of ‘security’. At the same time the same Pasha spearheaded the proclamation of the Gülhane edict that ushered in the Tanzimat reforms. But you argue this reform law was not a result of foreign pressure but a method by which Ottomans would demonstrate their liberal stripes and thus increase the likelihood of the Great Powers acting against the big enemies of Egypt and Russia. So do you think the Ottoman administration didn’t make a causal link between liberalisation and degree of loyalty of their far flung provinces? Or was the other cause the perceived French view that Egyptian rule was more benign and thus the Ottoman desire to show Constantinople as the real beacon of progress in the East?

The Gülhane Edict of November 1839 was prepared by a coalition of statesmen spearheaded by Foreign Minister Mustafa Resid Pașa and Grand Vizier Husrev Pașa. As you say, and it’s important to emphasize, the edict was promulgated about five months after a heavy defeat inflicted on the Ottoman imperial army by the Egyptian forces in Nizip in June 1839. The same week Sultan Mahmud II had passed away and succeeded by his 16-year old son Abdulmecid. And then, a few days after Husrev Pașa became Grand Vizier, the Grand Admiral, one of Husrev’s rivals, ran away from Istanbul and sought refuge in Mehmed Ali. Thus, in one week, the Ottoman Empire lost its sultan, fleet, and army. Mustafa Resid was in Europe when all these were transpiring, and he expected that the Powers would this time act collectively to protect Istanbul from the threat of Mehmed Ali. But he also saw in Paris that the French were supporting the cause of Mehmed Ali. In newspapers and journals the Pașa was depicted as the ‘Napoleon of the east’, or ‘the civilizer of the Orient’, which deeply disturbed the Ottoman Foreign Minister. He complained to Husrev in a letter that the Ottomans were “still called barbarians” in France, while Mehmed Ali’s expansionism and achievements (with the support of French officers under his service) were celebrated. The edict was drafted after Mustafa Resid’s return to Istanbul in the autumn within this context. Resid and Husrev had a double aim in preparing such a document. On the one hand, they addressed it to an Ottoman audience, heralding further liberties and security for the Ottoman subjects (and especially ministers). It was a promulgation of the rule of law, a pledge to protect the subjects, to an extent, from the Ottoman sultan’s arbitrary decisions, from which both Husrev and Mustafa had suffered in the past. The pledged reforms also had in view winning public support, especially in places like Syria whereby the peasants were already revolting against Mehmed Ali’s oppressive rule. The imperial regime sought to establish new ties of loyalty and certainly considered liberalisation as a means. On the other hand, with the 1839 edict, Mustafa Resid and Husrev strove to show that it was Istanbul, not Cairo, that was the civilised face of the Orient, as Resid explicitly wrote to European statesmen at the time. He looked to guarantee the support of the Powers to the Sublime Porte and against Mehmed Ali. The edict can be seen as a bold move to enable the Powers intervention. One year later, in the autumn of 1840, French agents would advise Mehmed Ali to promulgate a similar edict as the only means to keep Syria. But he was too late. So both points you make in the question are true. And they were not mutually exclusively. In fact, they were quite complimentary.

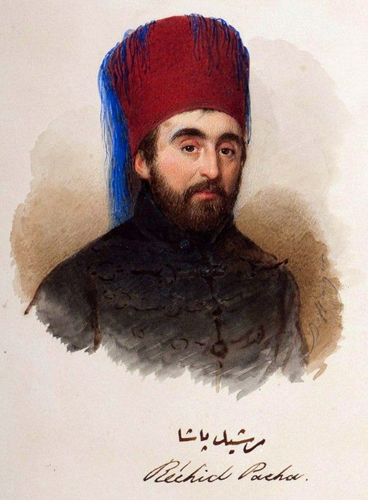

Mustafa Reşid Pasha (1800 – 1858) Ottoman statesman and diplomat, known best as the chief architect behind the Ottoman government reforms known as Tanzimat.

10- Richard Wood, the Ottoman/British agent arrived in Lebanon and distributed arms to the Christians of the region, who were traditionally under French protection. This was a clever move as the French public saw its ally, the Muslim leader of Egypt suppressing the Christians of Mount Lebanon and shortly afterwards the French Prime Minister Adolphe Thiers fell from office. Ottoman rule was renewed by Wood who also had an important part in the rule in that region. Do you think Richard Wood led 1840 intervention was a brilliant move by the British to achieve multiple aims, including driving the French from the region under the guise of liberating a region from tyranny?

I think Richard Wood was a fascinating figure and he played a very important role in the 1840 intervention, when he went to Syria and orchestrated the Lebanese revolt there. I’m currently working on an article about his time in Syria. It’s a pity that nothing in detail was published about his life and career before except the introduction by Cunningham in The Early Correspondence of Richard Wood.

In early 1840, Palmerston was uncertain about his policy on the Eastern Question. Even though he wanted the Powers to intervene in the civil war between Mehmed Ali and Istanbul, the Francophile members of his cabinet were obstructing him with the argument that the Eastern affairs were not worth jeopardising Britain’s relations with France. But the revolt of the Maronites, who were traditionally under French protectorate, and Mehmed Ali’s suppression of their revolt was a golden opportunity for Britain and the Ottoman Empire. This was how Mehmed Ali’s image as the Napoleon of the east could be upended. Palmerston admitted that until ‘this insurrection broke out I did not clearly see my way as to the means by which we could drive Mehemet [Ali] out of Syria.’ The fact that Thiers continued to support Mehmed Ali after the revolts and after the intervention of the four powers in September 1840 brought his time in office to an end. King Louis Philippe swallowed all his previous threats and decided not to escalate the tensions. By early 1841, when Mehmed Ali was driven out of Syria and the Ottoman commander and governor Izzet Pașa returned to Istanbul (after accidentally shooting himself in the leg), Richard Wood became the most influential man in Syria. In short, yes, pitting the Maronites against Mehmed Ali and the French was one of the most brilliant moves I’ve seen in the nineteenth-century diplomatic history. Though I’m not fully sure whose idea it was originally.

Lord Palmerston, twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century. Palmerston dominated British foreign policy during the period 1830 to 1865, when Britain stood at the height of its imperial power, painting by Francis Cruikshank, 1855 / Richard Wood (1806-1900), painting by Lieron Mayer, 1877.

Adolphe Thiers (1797 – 1877).

11- Richard Wood the following year was appointed as the British Consul in Damascus where he would play a key mediating role between local and Ottoman authorities during the Maronite-Druze wars in 1842 and 1845. Did the Ottoman authorities provide with Wood with much local power, such as hiring and firing local Emirs, because they trusted his personal abilities and knowledge and was this seriously curtailed when the Ottoman government changed in 1841 and Mustafa Rechid Pasa fell from power to be replaced by conservatives?

In late 1840 and early 1841, after the Ottoman rule was restored in Syria, for about six months, Wood was very influential. As the French agents there reported back to Paris, that the British dragoman was acting like a vizier and the ‘de facto governor general of Syria.’ But, as I explain in Dangerous Gifts, after the fall of Mustafa Resid in the spring of 1841, this changed. The appointment of a conservative Grand Vizier in spring 1841 not only changed the course of Euro-Ottoman relations for about four years. The new Grand Vizier Izzet Pașa and his ministers detested foreign interference in Ottoman domestic affairs. When two conservative pașas were appointed as the governor of Damascus and Sidon, Wood’s influence in Syria swiftly diminished. These pashas looked to undo many of the Tanzimat reforms. So it would be a mistake to consider the Tanzimat as a homogenous and monolithic process that lasted from 1839 to 1876. If anything, it was a discontinuous process and until the second half of the 1840s, its implementation in Syria was very limited.

12- These events came 70-80 years before these Arabic speaking lands were lost to the Ottomans with their participation in WWI on the Central Powers side and of course the region was carved up by French and British with the famous Sykes-Picot agreement. Do you think in the 1840s there was already in both camps a belief that eventually the region would fall out of the Ottoman grip and they were effectively jockeying into position to capture the prize when the situation was right?

Yes, the idea of partitioning the Ottoman Empire and founding new polities, satellite republics or colonies in its prized domains had long been entertained by Russian, French and British strategists. It was usually their differing interests and the risks that would come with such partition such as another total war in Europe that had prevented concrete actions. In 1807, Napoleon Bonaparte and Alexander I fell in a disagreement over Istanbul. Bonaparte refused to let Alexander control this key city. In the late 1820s, the French made explicit plans for erecting a Christian empire in Istanbul with an Orange king. But with the Treaty of Edirne in 1829, Russia already achieved its main objects in the south and was not sympathetic to the idea of partition. Lord Palmerston himself almost always opted for the preservation of the Ottoman Empire, and he was the first to defy the so-called ‘decline thesis’, the long-embraced belief that the Ottoman Empire was in decline and doomed to fall. He wrote in 1838 that “I must question that there is any process of decay going on in the Turkish Empire. [T]hose who say that the Turkish Empire is rapidly going from bad to worse ought rather to say that the other countries of Europe are year by year becoming better acquainted with the manifest and manifold defects of the organisation of Turkey…” But then, he also kept his options open when he wrote, ‘on the principle of “That I can do when all I have is gone” we can think of a confederation when unity [of the Ottoman Empire] shall have been proved to be impossible.’ In the mid-1840s, Russian and British ministers (in Robert Peel government) agreed that in the likely event of the fall of the Ottoman Empire, they would co-operate in its partition. In short, yes, the belief that Levant would one day fall out of the Ottoman grip was always there at the back of the minds of European strategists. Yet through until World War I, nobody could dare to make a move toward the empire’s total dismemberment. It would entail at least three powers within the Concert of Europe to cooperate and outnumber and outpower the others. Even though attempts were made for this (especially in 1858-9), they never succeeded. What happened instead was that the Powers nibble around the edges of the Ottoman Empire, starting with the invasion of Algiers, the Balkans, the Caucasus, Tunis, Egypt, Libya. The dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire proved to be a gradual process, just as its opening up to the global finance capitalism. But with Ottoman entry into the Great War along the side of the Central Powers, with the rise of Turkish and Arab nationalisms, and with the genocidal practices during the war, and the split of governance in Asia Minor between Istanbul and Ankara, the empire could longer survive. For the Middle East, the First World War ended in 1922-3, not in 1918, with the Lausanne Peace Treaty, which marked the end of the Eastern Question at least nominally, because the Ottoman Empire was no more.

13- Could you tell us about The Lausanne Project in which you are also involved?

Together with my colleague Jonathan Conlin, I’ve been running a project called the Lausanne Project since 2018. Even though there has been a raft of scholarship of post-World War I peace settlements, Lausanne has been the missing link in the literature especially in the English language. Aside from Sevtap Demirci’s book, no monograph has been published specifically on Lausanne Peace Conference and treaty in 1922-3 in English. Jonathan and I thought of co-authoring a monograph on the subject first. But since I was busy with finishing Dangerous Gifts, and Jonathan had other more immediate publication plans, to start with we decided to bring together young and more seasoned scholars, who specialise on different aspects of peace-making, and publish an edited volume provisionally titled, They All Made Peace – What is Peace? The Lausanne Conference and the New Middle East, 1922-3. I must say I’m very proud that a fantastic group of scholars have joined us for the edited volume. Thanks to funding from the Gingko Library and the Gulbenkian Foundation, we’ve managed to organise a series of writing workshops. In the volume, we aim to go beyond traditional diplomatic history that focuses on states and statesmen alone. We also look to re-introduce non-state transnational and transimperial actors, the financial undertones of humanitarian aid, the multinational companies’ quest for oil or the experience of the caricaturists such as Emery Kelen and Alois Derso, who met at Lausanne. We also aim to bring into attention the struggles of those groups that were not officially represented at the conference: Arabs, Armenians, Kurds, etc. In addition to the volume, the Lausanne Project is also organising a travelling exhibition around the caricatures of Derso and Kelen, and collaborating with Musée Historique Lausanne on a series of exhibitions in Lausanne itself. We also have a website (www.thelausanneproject.com), on which you can find information about the members of the project, and their recent publications. On the website, we publish a series of podcasts, interviews and blog posts on interwar relations between the Middle East and the rest of the world. In 2023, a bigger conference will be organised in London for the launch of the edited volume and with the participation of our members.

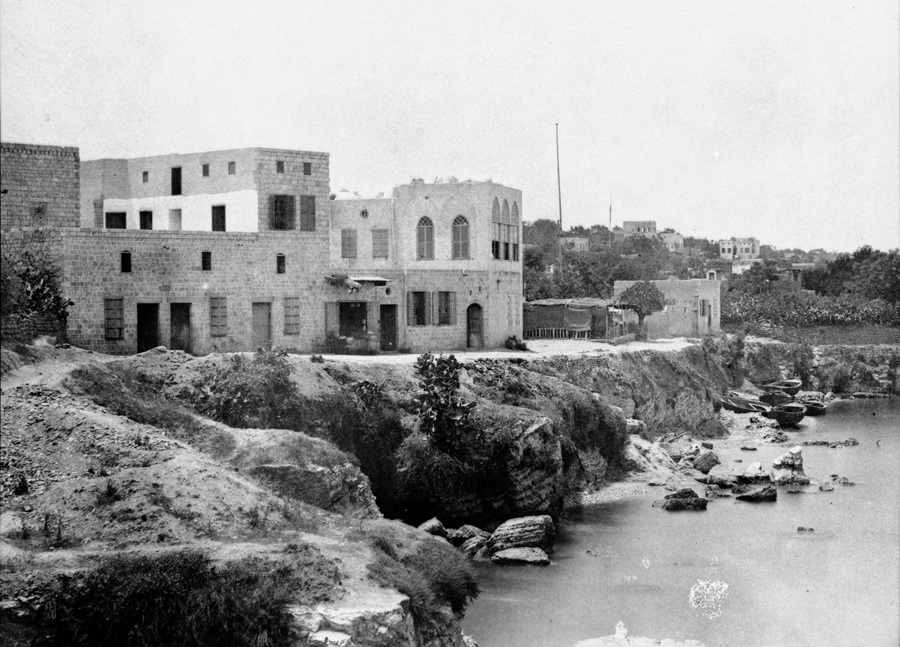

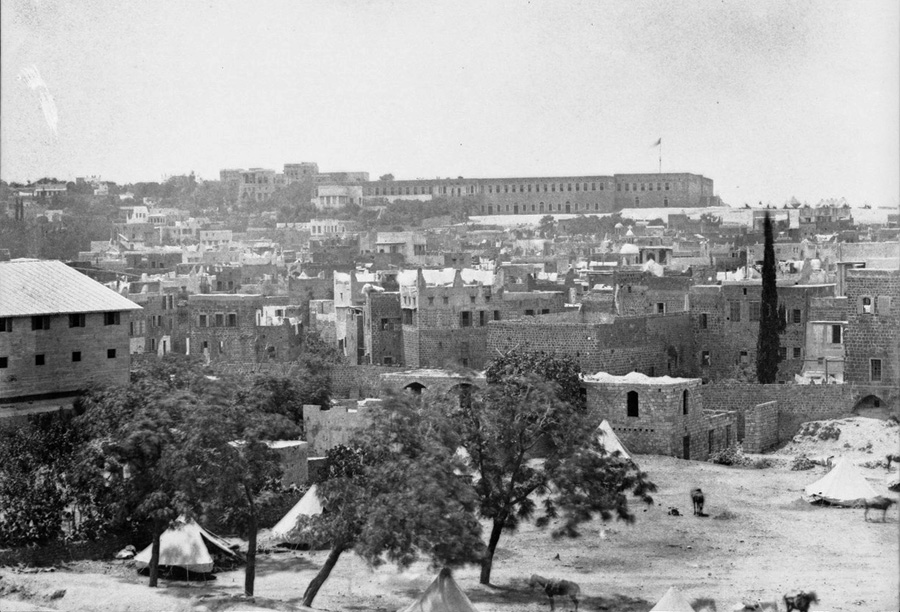

General views of Beirut in the 1860s.

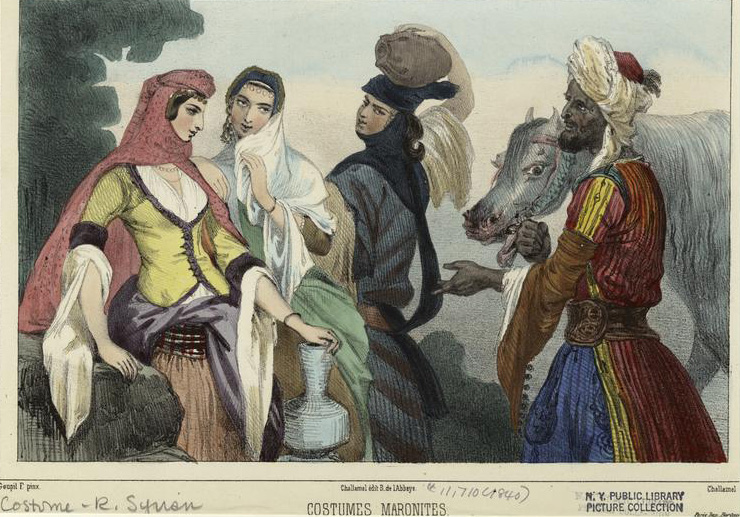

Depiction of Maronites in a French publication.

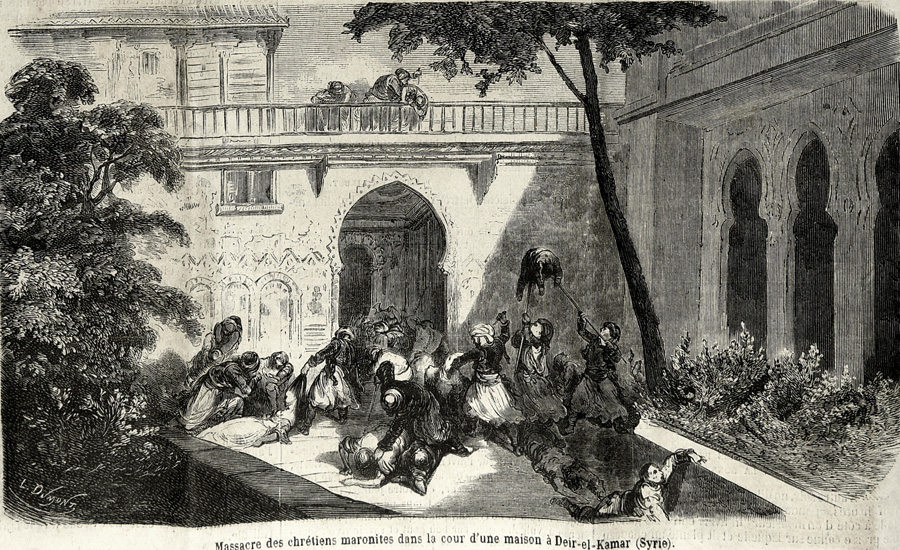

Depiction of a massacre of Maronites in a French publication.

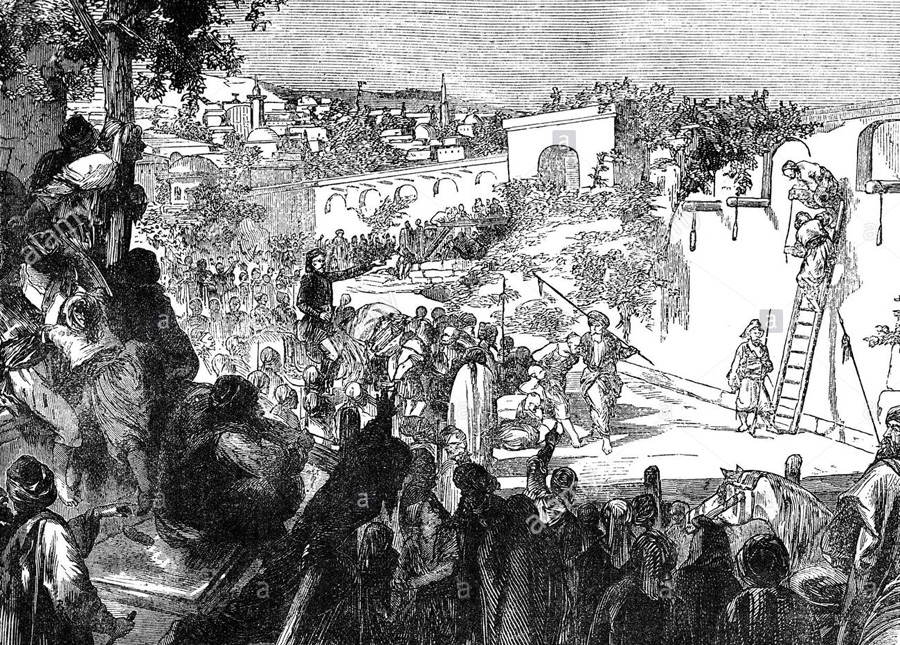

Depiction of the execution of Druze suspects during the 1860 civil war in Mount Lebanon.

Interview conducted by Craig Encer