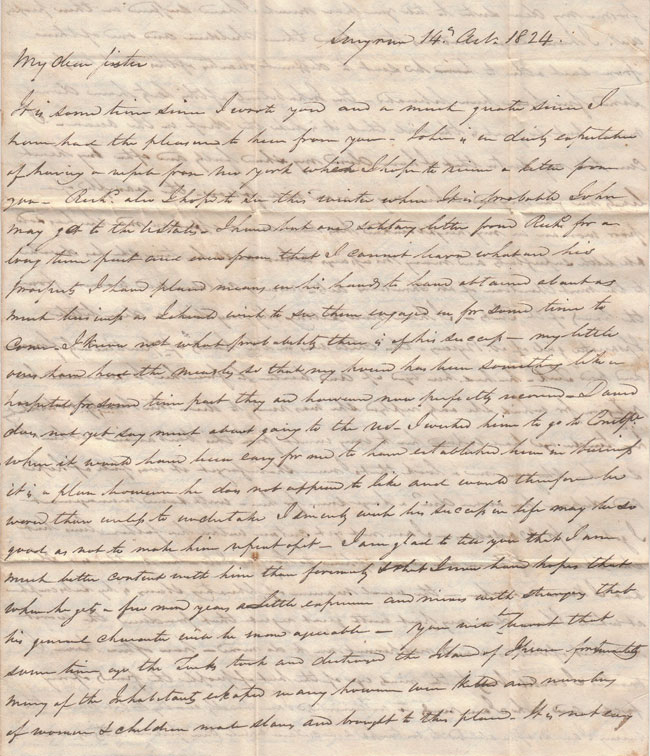

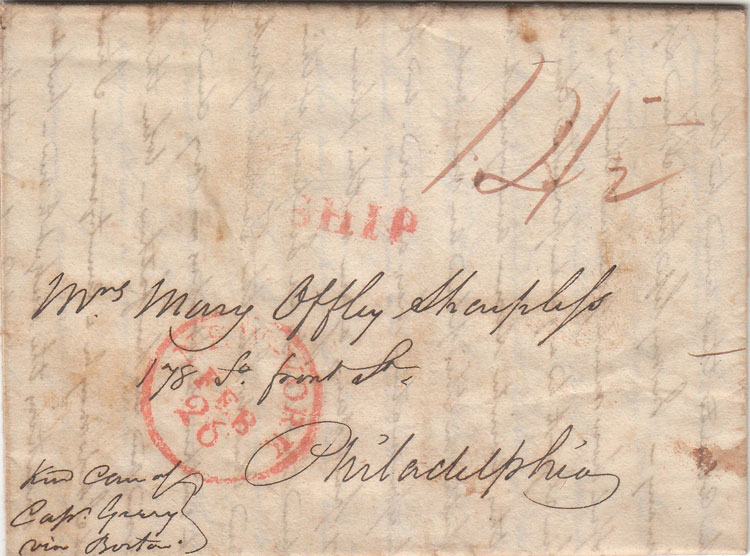

Letter dated at Smyrna, Turkey, October 14, 1824, from David Offley, to his sister, Mrs. Mary Offley Sharpless, at Philadelphia, Pa.

Folded letter has red “NEW-YORK” cds, red “SHIP” handstamp, and manuscript “14-1/2” rate. The NYC postmark is dated Feb. 26th, indicating that the letter took nearly 4-1/2 months reach the U.S.

The content concerns the atrocities committed by the Turks in capturing the Aegean Island of Ispara (now called Psara), killing many inhabitants, and enslaving many of the Greek Christian women and children. He writes how he bought the freedom (ransomed) of a 12 year old Greek girl, who had been tortured in an attempt by her Turkish master to force her to convert to Islam, and she is now living with him. Much more great content on this subject, and his hopes that Quakers in Philadelphia may contribute money for the ransoming of these Christian slaves. He also writes of the war between the Turks and the Greeks, of how naval battles often take place in view of Smyrna, and how the Greeks in Smyrna are better treated than previously.

Includes:

“You will have learnt that some time ago, the Turks took and destroyed the Island of Ipsara. Fortunately many of the inhabitants escaped. Many however, were killed, and numbers of women & children made slaves, and brought to this place. It is not easy for me, my dear Sister, to tell you how much I have suffered on these peoples’ account. I have seen Mothers torn from their children, and one of them from each other, to be sent to different quarters of this vast empire. Some few have been liberated. The inhabitants of this City have done much, but so great is the evil, that it is like the drop in the ocean. I can tell my sister that I have done my share fully, and often my heart leads me far beyond where my reason will follow.

The example of a poor woman in my neighbourhood has had much effect on me. She has sold all little superflueties and many necessaries, which with her time, she has devoted to the most Christian of all Christian acts - rescuing children and women from the hands of the Turks. I have now sitting by my side a dear little Ipsariater girl of about 12 years. This child was in the hands of a particularly ferocious and bad Turk. He had her tied up and beaten to force her to renounce her religion, for which she only replied she was ready to die. Her beauty notwithstanding, her tender age had exposed her to every insult from this barbarian. When I saw her, she gave me a look that I never shall forget. It was full of hope and despair. Her owner demanded a large sum for her. With some management, I got her for 320 dollars. I am not yet certain whether her father lives, but she shall never know the want of him so long as I do. Her mother is a slave, but I know not where.

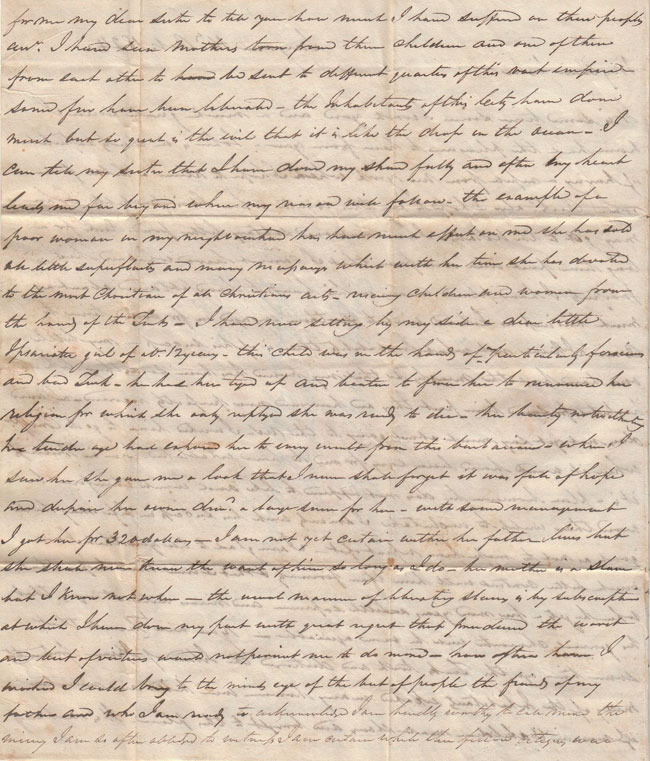

The usual manner of liberating slaves is by subscription, at which I have done my part with great regret that prudence, the worst and best of virtues, would not permit me to do more. How often have I wished I could bring to the mind’s eye of the best of people, the friends of my father, [his father was a Quaker minister], and who I am ready to acknowledge I am hardly worthy to call mine, the misery I am so often obliged to witness. I am certain... the friends of Philadelphia would readily afford their help to restore children to their parents, and rescue Christians from Mohametans. A warm hearted countryman of mine, whose warm and youthful feelings I am sometimes obliged to... after we had each expended in this work of charity, more than prudence would justify, proposed we should advance 2000 Sp. dollars, and purchase the amount of slaves for account of the friends of Philadelphia, and his heart, he said, told him our agency would not be denied, but that double the money would be sent me, and that if we were disappointed, to divide the loss between us. At his age, I should have agreed to this proposal. I do, however, believe with some influential friends to undertake the business, a sum might be collected that would be the means of relieving misery, and making glad the hearts of many. In my lifetime, I have spent much money in pleasure, but did mankind know & feel how much pleasure there was in doing good, how much of it there would be done. When I get to be a Quaker preacher, this should be my task.

I am much in hopes that this winter some arrangement will be made between the Turks and Greeks. The latter in this place are now well treated, and it is many months that no instance of assassination has occurred. We flatter ourselves with the hopes that all danger of witnessing past scenes again in this place will not occur. It is really astonishing to see the confidence that exists. All Europeans at this Country knows the roads & streets full of Greeks, and that which the Turkish & Greek fleets these days past have been fighting almost within sight of us...

You will of course read this letter to your Husband. May he be tempted to try if anything is to be done for the poor Christian slaves...”

|

|

|

|

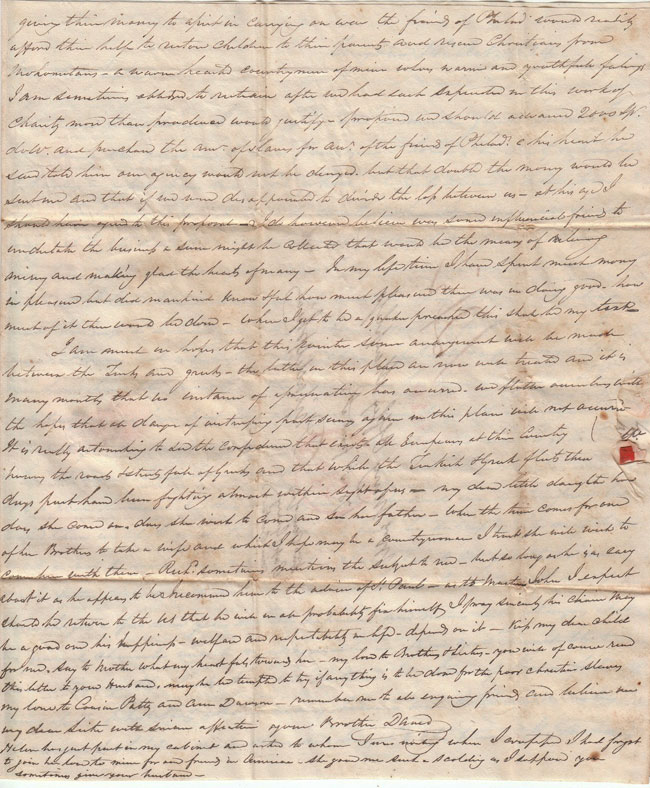

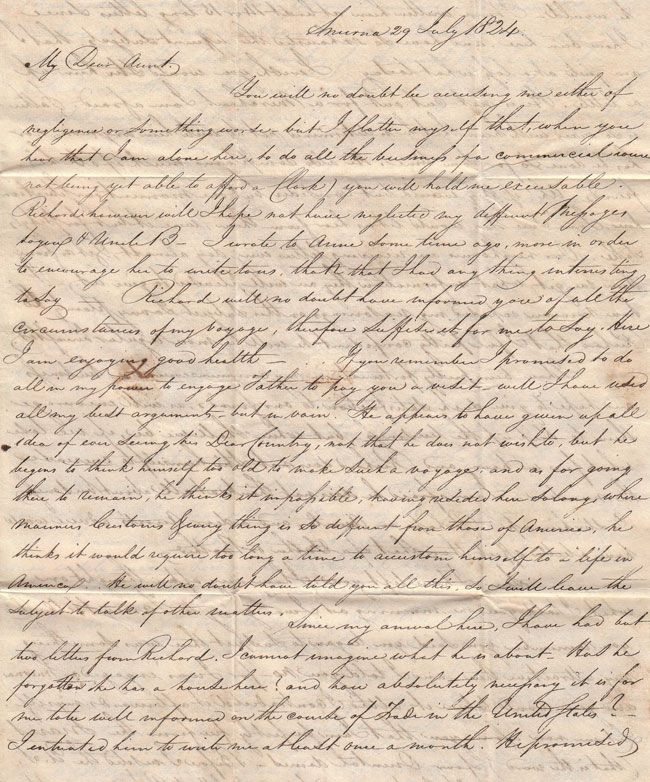

Below, letter dated at Smyrna, Turkey, July 29, 1824, from John Holmes Offley, to his Aunt, Mary Offley Sharpless, at Philadelphia, Pa. John Holmes Offley (1802-1845), was born in Virginia, and died in Georgetown, D.C. As a youth, he came to Turkey to live with his Father, David Offley (1779-1838).

He writes that he tried to persuade his father to visit the U.S., but his father feels that he is too old to make the voyage, and as for residing once more in the U.S., feels that he has been too long in Turkey and its customs, to be able to live in America again. Much more interesting content.

Includes:

“My Dear Aunt, You will no doubt be accusing me either of negligence or something worse, but I flatter myself that, when you hear that I am alone here, to do all the business of a commercial house not being yet able to afford a Clerk, you will hold me excusable. Richard [his brother, who also lived with their father in Turkey, and was at this time on a visit to the U.S.], however, will, I hope, not have neglected my different messages to you & Uncle B. [Blakey Sharpless, husband of his Aunt Mary]. Richard will no doubt have informed you of all the circumstances of my voyage... Here I am enjoying good health.

If you remember, I promised to do all in my power to engage Father to pay you a visit. Well, I have used all my best arguments, but in vain. He appears to have given up all idea of ever seeing his Dear Country; not that he does not wish to, but he begins to think himself too old to make such a voyage, and as for going there to remain, he thinks it impossible, having resided here so long, where manners, customs, & every thing is so different from those of America. He thinks it would require too long a time to accustom himself to life in America. He will no doubt have told you all this, so I will leave the subject to talk of other matters.

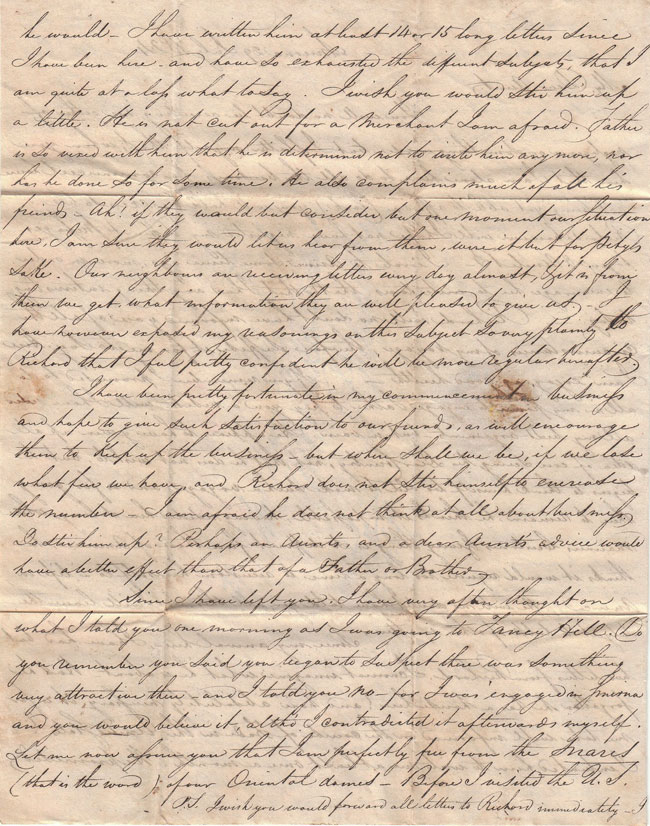

Since my arrival here, I have had but two letters from Richard. I cannot imagine what he is about. Has he forgotten he has a house here?, and how absolutely necessary it is for me to be well informed on the course of Trade in the United States? I entreated him to write me at least once a month. He promised he would. I have written him at least 14 or 15 long letters since I have been here, and have so exhausted the different subjects, that I am quite at a loss what to say. I wish you would stir him up a little. He is not cut out for a Merchant, I am afraid. Father is so vexed with him that he is determined not to write him anymore, nor has he done so for a long time. He also complains much of all his friends. Ah! if they would but consider but one moment our situation here, I am sure they would let us hear from them, were it but for pity’s sake. Our neighbours are receiving letters every day almost, & it is from them we get what information they are well pleased to give us. I have, however, exposed my reasonings on this subject so very plainly to Richard, that I feel pretty confident he will be more regular hereafter.

I have been pretty fortunate in my commencement in business, and hope to give such satisfaction to our friends, as will encourage them to keep up the business. But where shall we be, if we lose what few we have, and Richard does not stir himself to increase the number. I am afraid he does not think at all about business. Do stir him up. Perhaps an Aunt’s, and a dear Aunt’s advice would have a better effect than that of a Father or Brother.

Since I have left you, I have very often thought on what I told you one morning as I was going to Fancy Hill. Do you remember you said you began to suspect there was something very attractive there, and I told you no - for I was engaged in Smyrna, and you would believe it, altho’ I contradicted it afterwards myself. Let me now assure you that I am perfectly free from the snares (that is the word) of our Oriental dames. Before I visited the U.S., I had a different opinion from the one I now have. But now I see they can bear no comparison with our dear, dear Countrywomen. Ah! how differerent. Our fair ladies of Turkey, for the most part, have only pretentions without reality; are mere shadows without substance. I must however confess there are some very pretty, but what is beauty without the other qualities so necessary to make a man happy in the matrimonial life. When that is gone, there you are buried alive, with a lump of clay. Ah! give me the Yankee Girls - who join to beauty; talents, grace, good manners, and love. Here, they can easily talk of love, but I think they never feel it. Excuse me, my dear Aunt, for you know this is my favorite subject. Perhaps you might think it more adapted for the ear of an unmarried lady. I wonder if Richard ever got in love; he always told me it was great foolishness. How little he knows about it.

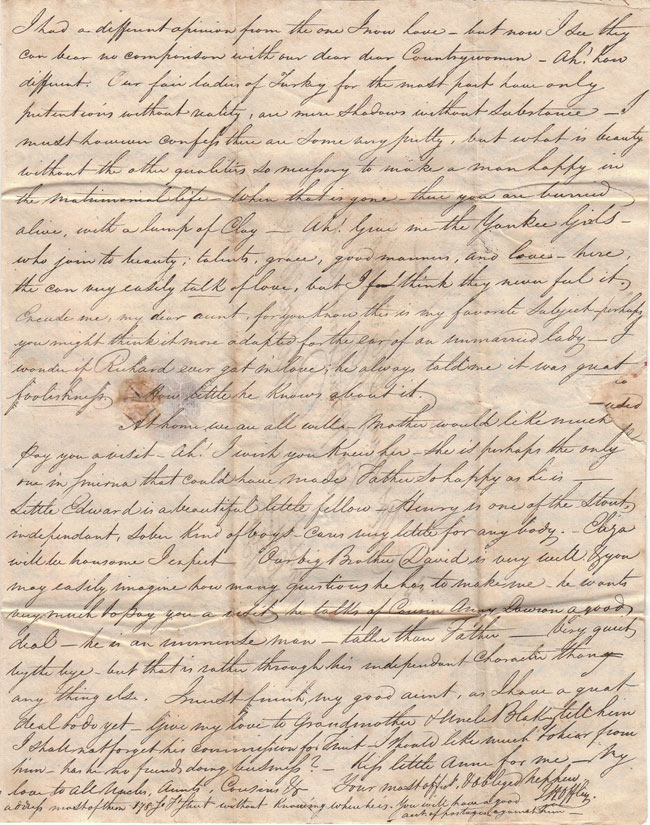

At home, we are all well. Mother would like much to pay you a visit. [“Mother” is not his birth mother, Mary Ann Greer, who his father divorced, but his father’s second wife, Helena Curtevich, a Greek woman he married in Smyrna in 1820]. Ah! I wish you knew her. She is perhaps the only one in Smyrna that could have made Father so happy as he is. Little Edward [a child born to his father & his 2nd wife] is a beautiful little fellow. Henry [another son of the 2nd marriage] is one of the stout, independent, sober kind of boys - cares very little for anybody. Eliza [a baby daughter born to them that year] will be handsome I expect. Our big Brother David, [his real brother, who also came to Turkey to live with their father - he is really a younger brother, the term “big” refers to his size for his age] is very well, & you may easily imagine how many questions he has to make me. He wants very much to pay you a visit. He talks of Cousin Anny Dawson a good deal. He is an immense man - taller than Father - very quiet by the bye, but that is rather through his independant character than any thing else...”

|

|

|

|