The memoirs of George Miniotis

George Poulimenos, 2009

Prologue:

The memoirs I have edited are about the adventures of a relative of mine, recently deceased, who was member of a resistance organization based in the area of Çeşme in the period 1941-1944. Head of this organization, a department of MI9, was Noel Rees, of the Smyrna family, who was at the time also the British Vice-Consul in Smyrna. The Giraud family of Smyrna is also mentioned in the memoirs.

The War

On the dawn of October 28, 1940 the Italians attacked Greece from their bases in Albania. After some initial successes, a Greek counter-offensive pushed them back into Albania, while some Italian prisoners were transferred to Chios Island, making a great impression on the local population.

There, in a village called Nenita, some 10 miles south of Chios Town, lived at this time George Miniotis together with his family, his father, Capt. Stamatis, his mother Aphrodite and his three younger brothers. In the same village resided one maternal and three paternal uncles.

Capt. Stamatis Miniotis was a seaman who out of necessity had taken up fishing to feed his family. On his small boat he took along George, then 15, and his younger brother Nikolis, as helpers.

After many months of fierce battles in the snow, the Greco-Italian war had come to a stalemate. Finally, in April 1941, the Germans came to the Italians’ aid and invaded Greece through Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. Three weeks later, Greece capitulated. The Germans occupied Chios on May 4, 1941, and the rest of Greece was split up into Italian, German and Bulgarian zones of occupation.

The Vice-Consul

Three months later, in August, Capt. Stamatis, along with his two sons, ostensibly went out for fishing, but instead rowed to Çeşme, a harbour in Turkey 13 miles from Chios. At the Çeşme lighthouse they were apprehended by Turkish soldiers, but on producing a mysterious document Capt. Stamatis was led to the military commander of Çeşme, where he met Nikos Diamantaras.

Diamantaras, a native of Oinousai, a group of minor Greek islands between Chios and Turkey, had escaped to Turkey just before the German occupation of Chios, in two yachts belonging to the Giraud family of Smyrna, which at the time were moored at Chios harbour (external site on the story of Capt. Doxis, captain of “Lillias”, one of the two Giraud yachts).

Hours before the British Consul of Chios, Noel Rees1, had also escaped to Turkey in a small caique named “Taxiarchis”. Rees was appointed British Vice-Consul in Smyrna and, as head of British Intelligence (MI9) in the area, was now trying to set up an escape network for the British who were stranded in occupied Greece. Diamantaras had become his right-hand man.

Noel Rees had known Capt. Stamatis as a fish supplier during his stay in Chios. He arranged to send him a note to visit him in Çeşme, through a double agent who had permission to trade with Turkey. The mysterious document Capt. Stamatis had with him was a license to enter Turkey, issued by the military commander of Çeşme. Soon Noel Rees arrived from Smyrna. He consulted with Diamantaras and Capt. Stamatis and they agreed to set up a resistance organization, with the object to gather information from Chios and nearby islands and send it to Çeşme.

After that, laden with provisions and narrowly avoiding an encounter with a German patrol boat, Capt. Stamatis and his sons rowed back to Chios.

Samos Island

Once back, Capt. Stamatis engaged two cousins living in the nearby seaside village of Katarrhaktis as informers. He then traveled to Chios Town and spoke to a friend named Kassiotis, a coffeehouse owner who was also an interpreter to the Germans, inducing him to cooperate. Finally he enlisted his brother, Capt. Michalis Miniotis, who after some thought was persuaded to become a member of the espionage group.

After some days Capt. Stamatis rowed again to Çeşme, where he met the British Vice-Consul and handed him any information he had gathered. He then asked for a better boat, as his boat was too small for such purposes. Noel Rees agreed and provided him with the necessary funds.

Capt. Stamatis had to go to the Italian-occupied Island of Samos to buy a new boat, as Chios had no shipyards. For this he needed a permit, so he went to Chios Town and requested one from the German harbor-master, ostensibly to barter mastic-gum with ceramic vessels.

Surprisingly, the permit was granted and Capt. Stamatis, his son George and his brother Michalis sailed to the Samian harbour of Karlovassi in the latter’s motor-driven boat. There they let the permit be approved by the Italian harbour-master, so they now had gathered all relevant seals and signatures and could let them be counterfeited by British Intelligence.

In Karlovassi Capt. Stamatis contacted an old friend and persuaded him, with the help of some provisions, especially potatoes, to enter the espionage group. The food situation in the islands was quickly becoming desperate, and it was very dangerous to be seen with such foodstuff, as it was obvious that it had originated in Turkey. The next day the brothers bought a 6-meter boat, recompensing mostly in food, did some trade for diversion and returned to Chios, towing with them the new vessel.

The Cretan

The Miniotis trio, Captains Stamatis and Michalis, and Stamatis’ young son George, rowed again with the new boat to Çeşme to report their actions.

Capt. Stamatis told the British Vice-Consul that the Chian organization had been expanded, including persons in key positions such as Dr. Zymaris and the Telephone Company director John Papastefanou.

Noel Rees in turn informed them of the general, bad, war situation and they discussed the Turkish attitude towards the Allies, which was cautious to downright hostile. Noel Rees asked Capt. Stamatis to extend the espionage network to the Dodecanese islands, which had been annexed by Italy since 1913. For the longer voyage he offered them the caique he had used to escape to Turkey, together with its crew. Capt. Stamatis accepted, and they then returned to Chios.

Back in the ‘30s, Capt. Stamatis had done some trading and smuggling in the southern Aegean, traveling to the Turkish port of Bodrum, the ancient Halicarnassus. During these journeys he often stopped at the small Arki Island, where he had a close friend, a refugee from Crete. It was Arki Island he now planned to visit.

He again asked for a permit, this time ostensibly to bring back a vessel he had left there some years ago, but he was only allowed to travel to Samos Island, and that only after the intervention of Kassiotis, the harbour-master’s Greek interpreter. There he was to ask for a new permit to Arki from the Italian harbour-master.

The Miniotis team sailed to Vathy harbor in Samos, where they fortunately obtained the permission to visit Arki Island, owing to a letter of introduction the German harbor-master had provided.

In Arki they met Capt. Stamatis’ old friend, the Cretan, who readily accepted to join their organization. He had very good relations with the Italians, could visit all of the Dodecanese and would provide them with information from this area, especially the Italian strongholds of Rhodes and Leros islands.

After pretending to repair the boat they had come to bring back, which was in bad condition, they left for Chios with some interesting information about the disposition of the Italian troops of the Dodecanese.

They made a rendezvous for their next meeting, only this time they would come secretly and by night.

The patrol

Capt. Stamatis and his two sons, George and Nikolis, visited Çeşme again to notify the British Vice-Consul. On leaving they filled their small boat with provisions, and it was then towed to a beach near their village in Chios by a motor-driven caique.

There they unloaded the foodstuff, left it in care of two relatives, and proceeded to the boat’s place of anchorage.

Unfortunately it was late by now, and before they had time to tug the boat to the shore, as was the Germans’ order, they heard footsteps. They just had time to secure the anchor and let some bow rope, so that the boat was now 5 metres from the shore, in 1 metre depth of water.

Soon they heard the footsteps come closer, and a dog started barking. It was the German patrol, which kept watch of the shoreline between the villages of Katarrhaktis and Nenita. They quickly hid in the bottom of the boat.

The Germans came and started shouting “Raus!” [out]. They tried to pull the boat by the rope to the shore, but the rope ring gave and the boat moved away from the shore. After some terrifying moments, where everybody held their breath, the Germans left, unable to do anything.

After some more minutes, Capt. Stamatis decided to go ashore, to try to warn his two relatives who had waited for them by the provisions, because the Germans were heading in their direction.

He quickly ran through the woods to them, and the three men succeeded just in time to load a donkey and themselves with the food and vanish out of sight, just as the Germans arrived at the scene.

The two children also left the boat after some more time and ran to the village. Capt. Stamatis hid all the provisions in a nearby monastery, and he also moved all the foodstuff from all the family’s houses there, afraid that the Germans would find out whose boat this was and search their houses.

During the next days Capt. Stamatis and his associates all lied low, as he was sure that the Germans had them under surveillance.

The trap

About a month later Capt. Stamatis and his 3 brothers were summoned to appear the next day at the police station of Kalamoti, a nearby village. The community secretary, who was pro-German, told them that all fishermen of Nenita and Katarrhaktis had received the same invitation.

The next day Capt. Stamatis and his brother Michalis went on foot to Kalamoti, while the other two brothers, who were not members of the resistance group, would follow later.

The police corporal who was recording the fishermen’s names, a true patriot, warned Capt. Stamatis that this invitation was a trap. The Germans wanted just the Miniotis brothers, and all the other fishers had been called to mislead them. He advised them to disappear at the first opportunity.

Indeed, after some time the two brothers pretended having to urinate and were accompanied outside for this purpose. Once there they quickly ran away, leaving the guard screaming he would shoot them when he got them.

The brothers hid in the bushes to wait for the other two brothers who were to come later. When they arrived, all four Miniotis brothers cautiously proceeded to the place they had left the new boat, entered it and rowed through a devious route to Turkey. Back at the police station, the corporal, after sufficient delay, called his commander, the police sergeant Vassiliadis, a collaborator of the Germans, who was outraged. He ordered a search for the Miniotis brothers, and released all the other fishermen.

The whole police force then went to Nenita and searched the Miniotis family houses, not finding the fugitives. They then ordered the mayor, also a pro-German, to search the whole village, which he did to no avail.

In Çeşme, the Miniotis brothers were safe, but very worried about the families they had left behind.

Captivity

Sergeant Vassiliadis informed his German superior of the situation, and the German ordered the arrest of all the remaining Miniotis family members, in case the four brothers could not be found.

Two days after the four brothers disappeared, the Miniotis houses were surrounded at dawn and all the Miniotis family members were captured, 21 persons overall, including women, small children and old people. Only George Miniotis, the eldest son of Capt. Stamatis, managed to escape by jumping out of the window and hiding in the woods.

The captives were led to Kalamoti, where Capt. Stamatis’ wife Aphrodite was interrogated. They then were locked in a shed for the night.

The next day the captives started on foot for Chios Town, 22 kilometers away, where they arrived on nightfall. They were afraid their final destination would be Thessaloniki, to a concentration camp, or even Germany.

After a two-week stay in prison and more interrogations, the family was moved to Vrontadhos, just north of Chios Town, and detained at the local police station. Back at Nenita, George Miniotis left his hideout and contacted his maternal uncle, who fortunately had been not arrested. He then went to the beach and saw with relief that the new boat was missing, meaning that the four brothers had succeeded in escaping. There he also witnessed some villagers looting the family’s storehouse. He considered escaping himself with the smaller boat to bring the news to his father, but his uncle dissuaded him, afraid that the Germans had left the boat there as bait.

In Çeşme, Capt. Stamatis was preparing to return to learn about his family, but then John Papastefanou, the telephone company director, succeeded in connecting the Zymaris clinic phone with Çeşme to tell them the news.

While waiting for an opportunity to liberate his family, Cap. Stamatis resumed his voyages to the Dodecanese, visiting his friend the Cretan in Arki Island and coming back with information. He now used a new route, passing between Samos Island and Turkey and making an intermediate stop at cape Canapitsa, where there was a Turkish outpost.

Two days before Christmas 1941 the police sergeant of Vrontadhos surprisingly announced to the detained Miniotis family that they were free to go. The German commander had just set the condition that they had to appear twice a week at the Vrontadhos police station, to sign at the station book. It was unbelievable. Immediately, the family returned to their village Nenita, just in time for Christmas. The family continued their trips to Vrontadhos police station till the middle of March, only towards the end it was just once a week, and the children and older people were exempted.

Then, one night, there was a knock at the door. The Miniotis family understood that they had come to rescue them.

Indeed, it was Capt. Michalis Miniotis. Quickly, all family members were gathered and proceeded to a secluded beach, where they were picked up by a caique. After some suspense, when the caique’s motor suddenly stopped, they succeeded in starting it up again to finally reach Çeşme.

There the Miniotis family was safe. They were of course worried of the possibility that Turkey could enter the war at the side of the Axis, but for such an occasion they had one of the Giraud yachts, the “Lady May” ready, to carry them all to Cyprus.

The refugees

By June 1942 many people were escaping from Greece, especially seamen with their vessels, and most of them were ending up in Çeşme. The British Vice-Consul enlisted the most daring, and a small fleet was assembled.

Noel Rees rented Kioste, a small protected cove north of Çeşme, ostensibly for recreation purposes, and the fleet of caiques was relocated there.

Rees let Capt. Stamatis choose a better boat for his trips to the southern Aegean, and he selected the Vice-Consul’s own yacht, “Serena”, a petrol-engine vessel which had formerly belonged to the American Consul in Volos.

Capt. Stamatis and his crew of four, including his son George, was responsible for the Dodecanese, while other boats traveled all around the Aegean, to Piraeus, Thessaloniki, Volos, Lesbos Island etc.

The base at Kioste was set up to include machine repair facilities, a shipyard and storage areas. There was even a British pigeon trainer there, for the carrier pigeons most vessels had with them while on a mission.

The refugee stream to Turkey was steadily increasing, so that Çeşme had become a huge refugee camp. Able men were selected and sent to Egypt, to enlist in Greek regiments and fight for the Allies.

Cap. Stamatis continued his frequent voyages to Arki Island, now with the new ship whose trip was shorter. While at Çeşme, he was active at the refugee reception committee.

In the meantime, while the conditions in Greece deteriorated further, the general war situation gradually improved.

In January 1943, every day 100 to 200 refugees were arriving at Çeşme. One of these was the former police corporal of Kalamoti, Capt. Stamatis’ savior, who stayed for a while at Çeşme before moving on to Egypt.

One month later, the Turks informed Nikos Diamantaras, the British Vice-Consul’s second-in-command, that a load of refugees were stranded on Makri, a small Turkish island close to the mainland.

Capt. Stamatis undertook the task of rescuing them. He approached the island with the bigger of the two Giraud yachts the “Lady May”, towing two boats along. After some initial havoc, as the refugees had been on the island for 3-4 days without provisions and were already desperate, Capt. Stamatis succeeded in picking up all 345 of them on the yacht and the two small boats.

They had been left there because the seamen who carried them to Turkey were afraid to land on the Turkish mainland, and they had misled the refugees by not telling them they were being left on an island.

This situation continued till the end of the war. Twice a week, a boat from Çeşme traveled to Makri and collected any refugees left there.

The police sergeant

One day, during the registration of refugees in Çeşme, a familiar name cropped up: Vassiliadis. He was the police sergeant responsible for the trap set up to capture the Miniotis brothers.

At his interrogation by Nikos Diamantaras and Capt. Stamatis he recounted his story. After the disappearance of the rest of the Miniotis family, he was threatened by the German deputy commander, a cruel Nazi, that he and his family would suffer if he didn’t find out where they were hiding. Then, his own deputy, the patriotic corporal, disappeared. The sergeant realized that he would be in grave danger if this would become known.

So he arranged to escape, together with his wife. They, together with 20 others, boarded a small caique and tried to cross the sea to Turkey. Unfortunately the caique was an old wreck. Soon a hole appeared at its bottom and the boat started to sink. The police sergeant managed to grab a piece of wood, and soon afterwards he located his wife. Together they stayed afloat, while all the others were drowning. After a while they saw the light of the lighthouse on Paspargos, the small Turkish island at the Chios straits. Swimming the whole night they managed to reach the island. There they were later found by a Turco-Cretan, a resident of the village of Çiftlik, the former Kato Panaghia, the place of origin of the Miniotis family when they were still living in Asia Minor before 1922.

The couple was rescued and brought to Çeşme. After a while they were transferred to Egypt, where they were kept under surveillance.

Meanwhile, in Chios, the Germans suspected Papastefanou, the telephone company director, and two other of the resistance group members. On learning this, Capt. Stamatis arranged to pick them up and bring them to Çeşme.

After a while, a second naval base was established in Agrelia bay, south of Çeşme. The caique fleet was split in two, with most of the vessels moving to the bigger new base.

Capt. Stamatis also moved to Agrelia, and continued from there with the yacht “Serena” and his crew the trips to Arki Island in the Dodecanese.

Cape Canapitsa

In May 1943, on the return leg of one of the trips to Arki Island, the “Serena” had a mechanical problem. Capt. Stamatis, unsure if they could repair the engine, let free two carrier pigeons, informing their base they were near Cape Canapitsa. After a while the crew succeeded in repairing the engine and they continued to Canapitsa, where they paused as usually. Unfortunately, the sergeant of the Turkish outpost there had been changed, and the new sergeant, a German sympathizer, wanted trouble.

He ignored the voyage permit shown to him and ordered to empty the boat of all things it contained. That was of course impossible, because the ship was heavily armed. It carried machine guns, Tommy-guns, hand grenades, dynamite sticks, magnetic mines etc., all stuffed away in inconspicuous-looking places.

After Capt. Stamatis denied they had anything on board, the sergeant brought an adz and a saw and started searching. When he found nothing but some containers full of sand, he phoned his superior, the military commander of Kuşadası, and then ordered the boat to sail there under custody.

Once in Kuşadası Capt. Stamatis was summoned for interrogation by the pro-German commander, a captain, while the other crew members were locked up in a room. Capt. Stamatis declared he was an agent of Turkish Security, showing the captain a document to demonstrate it. Nonetheless the Turkish captain had him stripped naked and found a sealed envelope addressed to the head of Turkish Security in Smyrna, and containing information about the Dodecanese.

Fortunately, while the captain contemplated if he should open the envelope, Nikos Myristis, a Greek responsible for refugee relief in Kuşadası, arrived. Having seen the yacht “Serena” in the harbor, he was worried and rushed to the commander’s building, having first informed Nikos Diamantaras in Çeşme.

Some hours later, the British Vice-Consul arrived in Kuşadası, bringing with him Selahattin, the head of Turkish Security. The pro-German captain was reprimanded, and the “Serena” crew released.

After this event, Capt. Stamatis changed their route to Arki Island, passing between Samos and Ikaria Islands instead of Cape Canapitsa. Later, they heard that the two pro-German Turks, the sergeant and the captain, were sent to Ankara and sentenced to prison for disobedience and not acknowledging official documents.

Arki Island

In the summer of 1943, Capt. Stamatis continued his visits to Arki Island. Once, they arrived there in the middle of the night, in the secluded cove where they usually met the Cretan, but he was not present. They decided to go to his home, just over a hill, to find out what was happening.

Capt. Stamatis took with him the other two crew members, but left his son George, fully armed, by the hidden ship. He told him to wait for half an hour and leave if they did not return. Should an Italian patrol appear, he was to shoot them, board the ship, which could be operated but just one man, and return to their base. George waited in anguish in the dark of the night, looking around with his night-vision glasses and hearing the bells of the sheep, which were in the vicinity. In the meantime, Capt. Stamatis reached the Cretan’s house and found out why he hadn’t come to the rendezvous. Some Italians had visited him, and they were still in his house drinking and singing.

The “Serena” crew waited till the Italians left and then, together with the Cretan, his son and his older daughter, started to walk towards the ship. George expected to see three people returning, but suddenly he saw six shadows descending the hill. Thinking they were an Italian patrol, he was ready to shoot them. Only in the last moment did he hear them speaking in Greek to each other, and the tragedy was averted.

They returned safely to the base in Agrelia. More than 20 ships were now there, and at the shore there was a mini-market, a cafe for the seamen and two big storehouses, one for ammunition and supplies, the other for diesel fuel. The petrol was stored in a vessel in the middle of Agrelia bay.

On the return leg of another trip to Arki Island, George Miniotis with his glasses saw on the stern side of the ship a small red light. The crew maneuvered the boat to avoid a collision, because the light belonged to a large enemy destroyer on collision course. After a little while, they saw more red lights. They now were in the middle of an enemy convoy heading north. Capt. Stamatis quickly ordered his crew to also put on a red light, and in this way they succeeded in fooling the enemy ships that they also belonged to the convoy. Some time after they were left behind and they then made a sharp turn and vanished.

In July 1943 the Allies had invaded Sicily, which they quickly conquered. In September Italy capitulated, and after that some important Italian-held South Aegean islands, Kos, Leros and Samos among them, were occupied by British forces.

Fireworks

As Italy had capitulated, there was now no need to continue the usual information-collecting trips to Arki Island. Capt. Stamatis undertook a new mission, to regularly carry two British officers to British-held Samos Island and back.

In the late afternoon before one of the trips to Samos Island, the “Serena” crew waited for a new engineer, as their regular one had been ill. When he arrived, he tried to start the engine in order to approach the fuel ship in the middle of the bay, to load some petrol.

Unfortunately, the engine would not start. George Miniotis, who was on board with his younger brother Nikolis, told him to unscrew the spark plugs and warm them in the small kitchen stove, a common trick employed at the time with such primitive engines.

The engineer would not take advice from a 17-year old boy, so he told George to bring a petroleum lamp in order to see better, as the flashlight’s battery was exhausted. George protested vehemently, because it was too dangerous to bring an open flame in the vicinity of the petrol engine.

The engineer seemed to agree, and told George to go under the deck and check the fuel leads for leakage. George did it, but before he could come out, he heard an explosion.

In the meantime, the engineer had done what he originally intended, he brought the petroleum lamp near the engine and the petrol had caught fire. Soon the fuel tank exploded, with George trapped under the deck, and his hands, soaked with petrol, caught fire.

Until he succeeded coming up, he was all on fire. He at once jumped overboard, while screaming to his brother to do likewise. He heard three splashes, the engineer and the two crew members jumping into the sea.

On board was also the captain of the fuel supply ship. He calmly pulled the rope that had bound a smaller boat behind “Serena” and together with Nikolis, George’s brother, they entered the smaller boat and rowed to the shore. The “Serena” crew also safely swam to the shore, and only George had some scalds on his hands. “Serena” was now burning like a torch, and from time to time there where explosions, as the ammunition on board caught fire. For two hours, Agrelia bay was like hell. The next day there was nothing left of the yacht. Only its burned hull could be discerned at the bottom of the sea.

Capt. Stamatis received another yacht, “Nereia”, and with it he resumed carrying the two British officers to Samos Island. On the return trip they found and arrested on a small island just outside Samian port Vathy two German spies, posing as British soldiers.

Adrias

Capt. Stamatis next carried the same two British officers with a caique to Gümüşlük, a small bay near Bodrum in Turkey. There the crew saw the Greek destroyer “Adrias” stranded on the beach. What had happened?

George Miniotis, curious to know, rowed in a small boat near the ship, where he was called on board by an acquaintance of his he had known from Çeşme. His friend recounted to George the story of “Adrias”.

The destroyer patrolled near Kalymnos Island, when it was struck by a mine. The ship’s bow broke away and sunk, but the watertight wall was not punctured and “Adrias” managed to stay afloat. The companion ship, the British destroyer “HMS Hurworth”, came near to help, but it was also struck by a mine and sunk quickly, while hundreds of sailors drowned (the story of this twin disaster).

After collecting many British from the sea, including the ship’s captain, the bowless “Adrias” managed to reach this small Turkish bay, where it was stranded awaiting developments.

Capt. Stamatis and crew slept there for the night, but they were suddenly awakened. A small British transport ship had sunk near a reef to the south, and they quickly sailed there to collect any survivors.

It was a dangerous operation to approach the reef during the night, but they succeeded in collecting some 30 sailors, who had been holding on the half-sunk transporter. Fortunately before sinking they had managed to inform via wireless the base at Bodrum of their accident.

The Miniotis team carried the shipwrecked sailors back to Gümüşlük and awaited new orders.

The dogfight

The next day Capt. Stamatis had to forward the two officers to British-held Leros Island. Leros had been the main Italian bastion in the Dodecanese before Italy’s capitulation.

When they arrived at Aghia Marina bay the guard at the outpost recommended them to move to the opposite side of the bay, secure the vessel and go ashore, because the area would soon be bombarded by German aircraft (eyewitness account). They followed the advice and rowed with the small boat to the beach, where a jeep picked up the two officers to drive them to the British headquarters.

Capt. Stamatis and crew waited in a small coffeehouse. After a few minutes a siren sounded and all quickly ran to a small cave nearby. From there they witnessed the action in the air. They heard the buzzing of the airplanes, then the machine guns, and then they saw bombs falling from the sky.

Then a British airplane was shot down, and they saw its pilot, who had managed to survive, slowly descending to the water with his parachute. Capt. Stamatis ran to the small boat and quickly rowed to the vicinity of the Miniotis caique, where the pilot had fallen into the sea. He picked him up and rapidly returned to the cave, where the pilot was given first aid.

Soon after that, when the battle had moved to the other side of the island, the same jeep came and carried the British pilot and Capt. Stamatis to the headquarters, where he was congratulated for his bravery in saving the pilot.

After a while the two British officers and Capt. Stamatis returned. They all rowed to their boat and quickly left the island, because the bombardments would soon start again. From afar they witnessed the battle starting again, while the sky was being painted in all colors from yellow to red.

On the return trip they encountered a small boat, with no people on it, but full of blood. They could not imagine what had happened.

The Miniotis caique went to Bodrum, where they passed the night on a British transporter ship, and the following day they returned to their base near Çeşme.

The partisans

During the last months the British Vice-Consul Noel Rees had tried to establish contact with the partisans of Euboea Island, just across the Aegean from Chios and very close to the Greek mainland. Unfortunately the partisans were very suspicious, and they had sent all the boats back, keeping the boat captains as hostages.

Now the Vice-Consul tried to persuade Capt. Stamatis to undertake this task. After some thought Capt. Stamatis accepted, on the condition that he would be provided with plenty of guns, ammunition and food, which he planned to offer to the partisans. After crossing the Aegean during the day, because at night the area was full of British submarines torpedoing every suspicious boat, they arrived at their destination in Euboea in the early afternoon. Soon four partisans appeared and ordered the captain to follow them.

Capt. Stamatis was led to a cave and presented to an Orthodox priest, who was the partisan captain. Capt. Stamatis told him they had come to cooperate with them, but the priest said he had heard all this before, and he probably would be detained, just like the other captains before him.

Then Capt. Stamatis showed him the list of the provisions he had in his boat and asked to speak to his superior. The priest could not believe they had brought all this stuff to them, and agreed to summon his superior, Colonel Charis.

The partisans proceeded to move the provisions from the boat to hiding places, and in the meantime Colonel Charis arrived. He was also astounded by the quantity and quality of the provisions Capt. Stamatis had brought them.

After that, the partisans became very friendly. They invited Capt. Stamatis for dinner and, while drinking some wine, he succeeded in obtaining their promise that the next time he came they would deliver the captive boat captains to him.

Capt. Stamatis then returned to his crew on “Nereia” and they got back to Çeşme, where Noel Rees congratulated them for their strategy and their success. Some days later “Nereia” returned with more provisions to Euboea, and they left taking the boat captains with them, 19 in all. On the return trip the weather became very bad and Capt. Stamatis had to change route and stay for two nights in a safe, hidden cove on the south side of Chios.

When they finally reached Çeşme there was a big party, organized by the captains’ families. The Turks wondered why they feasted, while their fatherland was under enemy occupation. To this the Greeks replied, “We go to war with songs!”

Transports

The general war situation was improving for the Allies, but the south Aegean islands on the contrary were being re-conquered by the Germans in a sea and airborne operation, one of the last series of German victories in the war.

Capt. Stamatis made a last trip to Samos Island, which at the time was being bombarded and would soon fall to the Germans. On the return leg, “Nereia” encountered two small boats in the middle of the sea. In them were Capt. Stamatis’ brother Aristophanes and his family, escaping from Leros Island, where they had been living for many years. They took them on board and towed the boats to Çeşme.

In December 1943 the Greek destroyer “Adrias”, still missing its prow, managed to sail from Gümüşlük to Alexandria in Egypt, to the great applause of the Allied forces stationed there.

Capt. Stamatis continued the voyages to Euboea Island to bring provisions and allied agents to the partisans. On the return trips he transported people escaping from mainland Greece to Turkey. On each trip ca. 120 people were carried to Turkey, half of them Jews, who after a short stop in Çeşme continued to the Middle East. Up to March 1944, ca. 1.500 persons had been transported to Çeşme.

In the last trip, Capt. Stamatis took 78 persons with him, most of them army officers and politicians. Just 8 miles out of Euboea, they saw a German patrol boat approaching. The Germans came to within 40 meters close and asked using a megaphone who they were. The “Nereia”, although a speedy motor yacht, was camouflaged so as to look like a derelict caique. Its crew answered they were merchants, carrying potatoes and coal from Volos to Chios Island.

Fortunately the German boat could not come any closer, because the weather was very bad. If the weather was better they could come near and search the ship, and they would find the fugitives, or a battle would ensue. So, after a while, the German patrol continued its course and “Nereia” picked up speed and sailed for Çeşme, traveling during the night when the voyages were most dangerous.

Tenedos Island

Now the Vice-Consul summoned Capt. Stamatis and told him to cease the trips to Euboea. He was to organize an observation mission instead. One or two boats would be positioned in appropriate spots to detect enemy vessels and inform headquarters of their movement, or even try to capture them.

Capt. Stamatis decided to send two caiques on this mission, one to Mavria Islet, north of Tenedos Island and very near to the shore of Troy and the entrance to the Dardanelles, and the other to Ayazmat, a place opposite Mytilene harbor overlooking the strait. Since a member of the second caique had fallen ill, his son George replaced him.

A few miles north of Çeşme the two caiques encountered another boat, sailing slowly to Mytilene, with white smoke coming out of its chimney. They approached and found out it was manned by Greeks and was carrying a cargo of sugar for the Germans. The crew had sold the diesel provided by the Germans to buy much needed food, and they were now traveling by burning olive oil.

The enemy vessel was captured and escorted back to their base by the first caique, while the second, “Taxiarchis”, continued to Ayazmat. There they stayed for three weeks observing ship movements, and were then ordered to relocate to Mavria Islet, where they stayed for another two weeks.

Every Saturday they went to Tenedos to buy provisions and attend the church, since Tenedos, although Turkish, was inhabited mainly by Greeks. The third Saturday they saw a big caique moored at Tenedos harbor. They inquired discretely and found out the ship was Chian and transported potatoes and eggs for the Germans in Mytilene. It was immobilized due to a machine problem.

The “Taxiarchis” captain offered to tow the ship to its destination, and the big caique’s captain, Capt. Triantafyllos, accepted.

After rounding the Troad cape, the “Taxiarchis” crew captured the enemy caique and they left George Miniotis, armed with a machine gun, as a guard. George constrained the crew to its cabins and waited for the night to pass by.

After staying awake the whole night and the whole next day, George Miniotis saw the sun set again. They had four more hours to arrive at their base, but the weather was now worsening.

Just after dark George saw a shadow moving on the deck in the direction of the toilette. He was Capt. Triantafyllos. Suddenly, he stumbled and fell into the sea. George at once went to the stern, where the captured caique was towing a small boat. He pulled the rope and entered the boat, and, looking around, he saw Capt. Triantafyllos just two meters from the boat. He pulled him by the collar and, after much effort, succeeded in bringing him into the boat and in climbing back into the caique. Capt. Triantafyllos was saved. Finally, “Taxiarchis” reached their base at Kioste, from where the captured ship and its crew was escorted to Cyprus.

Interlude

At the end of April 1944 Dr. Zymaris, the resistance organization head in Chios, was arrested by the Germans. Soon he was sent to a concentration camp in Thessaloniki, but there he was defended by the former Chios Secret Police chief, who had been transferred to Thessaloniki, and thus he avoided being sent to Germany.

Back in Çeşme, all naval operations in both bases had been suspended. The crews now just waited, and all they did was to listen to the news.

In Egypt a new Greek government had been formed, in Italy the Allies were advancing, and on the eastern front the Russians did the same. But the most important event was due to happen in France.

Finally, at the beginning of June, the Allies landed with tremendous forces in Normandy. After initial difficulties, they succeeded in establishing a bridgehead. In the course of the following two months, nearly all of France, including Paris, “the European capital”, would be liberated.

In Egypt, the Greek army had in the meantime revolted, refusing to fight in Italy. Just a brigade remained faithful to the Greek government and fought at Rimini, the others rebelled and were put into concentration camps, the “wires”, by the British. Some said the communists were behind it, but others suspected the British themselves, that they wanted to discredit the Greek army, so that after the war Greece would not put forward any demands for union with Greece of Northern Epirus (southern Albania), Cyprus and the Dodecanese.

Yeni Liman

Capt. Michalis, Capt. Stamatis’ brother, decided to leave for Egypt because of health problems, but before that he was assigned a last mission. He had to carry provisions to a detachment of the Greek Sacred Regiment, which at the time was stationed at Port Ajano, opposite Lesbos Island. He took George, his nephew, with him.

After completing the mission they made course to return to their base, but in the late afternoon the weather was so bad, that they could not continue. While searching for a safe anchorage, they saw some faint lights near Cape Karaburnu.

They approached the spot, which unfortunately could not protect them from the bad weather, but it was sandy enough, so they could come very close to the beach. While anchoring the boat, they heard someone asking them who they were. George answered they were from Çesme and that they had authorization papers. The Turk left and returned with another three men, telling them to come nearer to the shore. They did that and, because the weather was worsening, they decided to beach the boat in order to save it, as the shore was all sand. One of the Turks, a corporal in military uniform, said they were Greek infidels, made a move to draw his pistol and demanded to see their papers, while the two Miniotes were trying to save the ship.

Only after promising them 100 Turkish liras did the Turks condescend to help beach the ship. One of them ran to a small coffeehouse nearby and brought 20 men for help. After beaching the ship the corporal examined their papers, and then they all relaxed at the coffeehouse. The mood had now improved.

The small harbour was called Yeni Liman (“new harbor”), but it was hardly a harbour. That night the Miniotes slept in the boat, one of them always on guard with the machine-gun. The next day the Turks helped them push the boat back into the sea, the Miniotes giving them one lira each, and they returned to Çeşme.

In the following days Capt. Stamatis tried to intercept a German patrol boat but failed, as the boat didn’t appear due to mechanical problems. Some time later the patrol boat was sabotaged by its Greek engineer and it sunk.

The Liberation

In the morning of September 10th, big explosions were heard in Çeşme, coming from the direction of Chios harbour. It was the Germans, destroying their ammunition depots, as they were leaving. Chios was the first Greek island to be liberated! The British Vice-Consul now called all Greek boat crews and told them they should wait for a while and not return at once to their homes. Indeed, one month later the Vice-Consul called them up again, and after giving British discharge papers to each, released them from service.

This was the end of the Miniotis family collaboration with Noel Rees.

Capt. Stamatis now loaded the “Nereia” with 4 tons of provisions and sailed to his home village, Nenita, where he handed it out to the local population. He himself and his family did not return to the village, but opted to settle in Chios town instead. As Chios was now liberated, while the Greek mainland was not, Chios became a base of Allied forces, Australians, New Zealanders, Indians etc. Even the Greek “Sacred Band” set up their headquarters in Chios, from where they operated to liberate the Greek islands that still remained in German hands.

After a while Athens was emptied of Germans, and the exile Greek government arrived there, backed up by the British. Large parts of the countryside were at this time occupied by communist resistance fighters. In December 1944 large demonstrations were organized by them in Athens, having as a banner the words “Power to the people”. For a month, the loyal Greek troops and the British fought against the communists in the streets of Athens, and they finally succeeded in ousting them of the Greek capital.

In Europe the war had been going on, but now inside Germany. In the Far East the Allies had liberated many countries and they began encircling Japan itself. In the spring of 1945 the Americans met the Russian army at the Elbe River, and soon Berlin itself was seized. The Japanese on the contrary continued to fight, and only after two atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, could they be persuaded to surrender. Thus World War II had finally come to an end.

Greece, according to the agreements, was to come under the influence of Great Britain, but the communists would not accept it. Aided by Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, they rebelled again. While the whole world was recovering from the destructions caused by the war, in Greece a new civil war started, which would last till 1949.

3 later incidents

1st incident:

After the war, Capt. Stamatis and his sons started back from the humble beginnings in Chios town. At first they had only one small boat, but soon they acquired two bigger caiques, with which they did trade, mainly with the Dodecanese.

One day, when George Miniotis was at their harbor office, an old man entered and asked him if he was really George Miniotis. After George affirmed, the old man told him he was Capt. Triantafyllos, the man George had saved by fishing him out of the sea when returning from Tenedos.

Capt. Triantafyllos thanked George for saving him and told him the story of his captivity in Cyprus, where he had stayed for two years. He also thanked George for the foodstuff sent to his family during his absence. It turned out that it was a relative of the Miniotis family who was providing them with food during this period.

2nd incident:

On February 1947 Capt. Stamatis and his son George arrived at the still British-held Rhodes. There they had been buying machinery and other stuff from the Italian depots to sell them at home in Chios.

While waiting at the customs for their pass, they heard an elderly gentleman, a foreigner, ask the customs officer if he knew Capt. Stamatis Miniotis. The officer naturally had not known him, but George, with his limited knowledge of English, anticipated him and answered, pointing at his father, “This is Capt. Stamatis Miniotis”.

It turned out the foreigner was an industrialist from Liverpool, and had come with his wife to Greece in order to meet Capt. Stamatis. He was the father of the airman Capt. Stamatis had saved during his short stay in Leros Island. Why he ended up in Rhodes instead of Chios remains a mystery.

After the Englishman was sure he had found the right person, he profoundly thanked Capt. Stamatis for rescuing his son. He had had two sons, both with the R.A.F., but one of them had been killed over the English Channel.

The Englishman introduced Capt. Stamatis and George to his wife and entertained them for several days. Before leaving, he invited them to visit them in Liverpool whenever they wanted.

3rd incident:

Ten days after that, Capt. Stamatis Miniotis received an invitation from the British Embassy to appear at a ceremony in Athens where he, along with 36 others, would be decorated in recognition for his services. He could take along three relatives. Accordingly, his brother Michalis, his wife Aphrodite and his son George accompanied him.

After a moving speech by the Ambassador, the 37 persons, 9 of them from the Noel Rees organization, received the King’s Medal for Courage in the Cause of Freedom. What impressed George Miniotis was that among the decorated persons there was a 5-year old boy. The child’s grandfather recounted his story and resolved their wonder.

The boy was now an orphan. His father, an officer, escaped during the war to Egypt and joined the Greek navy, while his mother, the grandfather’s daughter, also worked for a resistance organization in Athens. The father was killed in 1943, when his ship, the destroyer “Adrias”, was struck by a mine.

At this time, George and the rest of the Miniotis family burst into tears, as they remembered their own encounter with the “Adrias” at Gümüşlük. Then the grandfather continued his story.

The child’s mother had a nervous breakdown when she heard of her husband’s death, but some months later she resumed her job for the resistance with renewed zeal. One night, while she was transporting some documents, and carrying the baby with her to divert suspicion, she was entrapped by the Germans. Fortunately she succeeded unnoticed to leave the child with the documents on a doorstep before being captured and transferred to Secret Police headquarters.

There she was interrogated under torture for one month and then she died. Her parents could do nothing to save her.

The baby was found by a retired officer of the army. The documents were forwarded to their recipient and the boy given to the retired officer’s childless granddaughter to care for it.

After much searching, the grandfather located the baby and retrieved it. He was now alone, as his wife had died of a stroke when she had first seen her abused daughter during her captivity.

This was the story of the decorated 5-year old boy, forever to remain in George Miniotis’ memory.

Wish

George Miniotis, the author, contemplates the events of the war and asks himself if such a war could happen again. He hopes not, as he doesn’t think such monsters as the Nazis could ever exist again.

He could never believe that the war would someday end, without a disaster happening to him or his family. It was certainly a miracle that, with the help of God, all survived the war unscathed.

All the more so because Capt. Stamatis Miniotis was first on the Germans’ wanted list, as the British Vice-Consul had confided to him just after the end of the war.

George Miniotis concludes his story with a wish:

“Let there never be another war”.

|

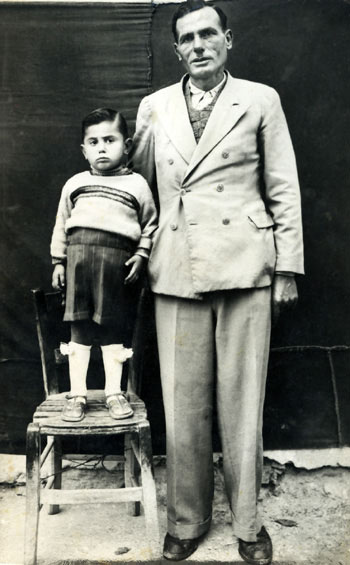

George Miniotis while serving his term

at the Greek navy

Prologue:

The memoirs I have edited are about the adventures of a relative of mine, recently deceased, who was member of a resistance organization based in the area of Çeşme in the period 1941-1944. Head of this organization, a department of MI9, was Noel Rees, of the Smyrna family, who was at the time also the British Vice-Consul in Smyrna. The Giraud family of Smyrna is also mentioned in the memoirs.

The War

On the dawn of October 28, 1940 the Italians attacked Greece from their bases in Albania. After some initial successes, a Greek counter-offensive pushed them back into Albania, while some Italian prisoners were transferred to Chios Island, making a great impression on the local population.

There, in a village called Nenita, some 10 miles south of Chios Town, lived at this time George Miniotis together with his family, his father, Capt. Stamatis, his mother Aphrodite and his three younger brothers. In the same village resided one maternal and three paternal uncles.

Capt. Stamatis Miniotis was a seaman who out of necessity had taken up fishing to feed his family. On his small boat he took along George, then 15, and his younger brother Nikolis, as helpers.

After many months of fierce battles in the snow, the Greco-Italian war had come to a stalemate. Finally, in April 1941, the Germans came to the Italians’ aid and invaded Greece through Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. Three weeks later, Greece capitulated. The Germans occupied Chios on May 4, 1941, and the rest of Greece was split up into Italian, German and Bulgarian zones of occupation.

The Vice-Consul

Three months later, in August, Capt. Stamatis, along with his two sons, ostensibly went out for fishing, but instead rowed to Çeşme, a harbour in Turkey 13 miles from Chios. At the Çeşme lighthouse they were apprehended by Turkish soldiers, but on producing a mysterious document Capt. Stamatis was led to the military commander of Çeşme, where he met Nikos Diamantaras.

Diamantaras, a native of Oinousai, a group of minor Greek islands between Chios and Turkey, had escaped to Turkey just before the German occupation of Chios, in two yachts belonging to the Giraud family of Smyrna, which at the time were moored at Chios harbour (external site on the story of Capt. Doxis, captain of “Lillias”, one of the two Giraud yachts).

Hours before the British Consul of Chios, Noel Rees1, had also escaped to Turkey in a small caique named “Taxiarchis”. Rees was appointed British Vice-Consul in Smyrna and, as head of British Intelligence (MI9) in the area, was now trying to set up an escape network for the British who were stranded in occupied Greece. Diamantaras had become his right-hand man.

Noel Rees had known Capt. Stamatis as a fish supplier during his stay in Chios. He arranged to send him a note to visit him in Çeşme, through a double agent who had permission to trade with Turkey. The mysterious document Capt. Stamatis had with him was a license to enter Turkey, issued by the military commander of Çeşme. Soon Noel Rees arrived from Smyrna. He consulted with Diamantaras and Capt. Stamatis and they agreed to set up a resistance organization, with the object to gather information from Chios and nearby islands and send it to Çeşme.

After that, laden with provisions and narrowly avoiding an encounter with a German patrol boat, Capt. Stamatis and his sons rowed back to Chios.

Samos Island

Once back, Capt. Stamatis engaged two cousins living in the nearby seaside village of Katarrhaktis as informers. He then traveled to Chios Town and spoke to a friend named Kassiotis, a coffeehouse owner who was also an interpreter to the Germans, inducing him to cooperate. Finally he enlisted his brother, Capt. Michalis Miniotis, who after some thought was persuaded to become a member of the espionage group.

After some days Capt. Stamatis rowed again to Çeşme, where he met the British Vice-Consul and handed him any information he had gathered. He then asked for a better boat, as his boat was too small for such purposes. Noel Rees agreed and provided him with the necessary funds.

Capt. Stamatis had to go to the Italian-occupied Island of Samos to buy a new boat, as Chios had no shipyards. For this he needed a permit, so he went to Chios Town and requested one from the German harbor-master, ostensibly to barter mastic-gum with ceramic vessels.

Surprisingly, the permit was granted and Capt. Stamatis, his son George and his brother Michalis sailed to the Samian harbour of Karlovassi in the latter’s motor-driven boat. There they let the permit be approved by the Italian harbour-master, so they now had gathered all relevant seals and signatures and could let them be counterfeited by British Intelligence.

In Karlovassi Capt. Stamatis contacted an old friend and persuaded him, with the help of some provisions, especially potatoes, to enter the espionage group. The food situation in the islands was quickly becoming desperate, and it was very dangerous to be seen with such foodstuff, as it was obvious that it had originated in Turkey. The next day the brothers bought a 6-meter boat, recompensing mostly in food, did some trade for diversion and returned to Chios, towing with them the new vessel.

The Cretan

The Miniotis trio, Captains Stamatis and Michalis, and Stamatis’ young son George, rowed again with the new boat to Çeşme to report their actions.

Capt. Stamatis told the British Vice-Consul that the Chian organization had been expanded, including persons in key positions such as Dr. Zymaris and the Telephone Company director John Papastefanou.

Noel Rees in turn informed them of the general, bad, war situation and they discussed the Turkish attitude towards the Allies, which was cautious to downright hostile. Noel Rees asked Capt. Stamatis to extend the espionage network to the Dodecanese islands, which had been annexed by Italy since 1913. For the longer voyage he offered them the caique he had used to escape to Turkey, together with its crew. Capt. Stamatis accepted, and they then returned to Chios.

Back in the ‘30s, Capt. Stamatis had done some trading and smuggling in the southern Aegean, traveling to the Turkish port of Bodrum, the ancient Halicarnassus. During these journeys he often stopped at the small Arki Island, where he had a close friend, a refugee from Crete. It was Arki Island he now planned to visit.

He again asked for a permit, this time ostensibly to bring back a vessel he had left there some years ago, but he was only allowed to travel to Samos Island, and that only after the intervention of Kassiotis, the harbour-master’s Greek interpreter. There he was to ask for a new permit to Arki from the Italian harbour-master.

The Miniotis team sailed to Vathy harbor in Samos, where they fortunately obtained the permission to visit Arki Island, owing to a letter of introduction the German harbor-master had provided.

In Arki they met Capt. Stamatis’ old friend, the Cretan, who readily accepted to join their organization. He had very good relations with the Italians, could visit all of the Dodecanese and would provide them with information from this area, especially the Italian strongholds of Rhodes and Leros islands.

After pretending to repair the boat they had come to bring back, which was in bad condition, they left for Chios with some interesting information about the disposition of the Italian troops of the Dodecanese.

They made a rendezvous for their next meeting, only this time they would come secretly and by night.

The patrol

Capt. Stamatis and his two sons, George and Nikolis, visited Çeşme again to notify the British Vice-Consul. On leaving they filled their small boat with provisions, and it was then towed to a beach near their village in Chios by a motor-driven caique.

There they unloaded the foodstuff, left it in care of two relatives, and proceeded to the boat’s place of anchorage.

Unfortunately it was late by now, and before they had time to tug the boat to the shore, as was the Germans’ order, they heard footsteps. They just had time to secure the anchor and let some bow rope, so that the boat was now 5 metres from the shore, in 1 metre depth of water.

Soon they heard the footsteps come closer, and a dog started barking. It was the German patrol, which kept watch of the shoreline between the villages of Katarrhaktis and Nenita. They quickly hid in the bottom of the boat.

The Germans came and started shouting “Raus!” [out]. They tried to pull the boat by the rope to the shore, but the rope ring gave and the boat moved away from the shore. After some terrifying moments, where everybody held their breath, the Germans left, unable to do anything.

After some more minutes, Capt. Stamatis decided to go ashore, to try to warn his two relatives who had waited for them by the provisions, because the Germans were heading in their direction.

He quickly ran through the woods to them, and the three men succeeded just in time to load a donkey and themselves with the food and vanish out of sight, just as the Germans arrived at the scene.

The two children also left the boat after some more time and ran to the village. Capt. Stamatis hid all the provisions in a nearby monastery, and he also moved all the foodstuff from all the family’s houses there, afraid that the Germans would find out whose boat this was and search their houses.

During the next days Capt. Stamatis and his associates all lied low, as he was sure that the Germans had them under surveillance.

The trap

About a month later Capt. Stamatis and his 3 brothers were summoned to appear the next day at the police station of Kalamoti, a nearby village. The community secretary, who was pro-German, told them that all fishermen of Nenita and Katarrhaktis had received the same invitation.

The next day Capt. Stamatis and his brother Michalis went on foot to Kalamoti, while the other two brothers, who were not members of the resistance group, would follow later.

The police corporal who was recording the fishermen’s names, a true patriot, warned Capt. Stamatis that this invitation was a trap. The Germans wanted just the Miniotis brothers, and all the other fishers had been called to mislead them. He advised them to disappear at the first opportunity.

Indeed, after some time the two brothers pretended having to urinate and were accompanied outside for this purpose. Once there they quickly ran away, leaving the guard screaming he would shoot them when he got them.

The brothers hid in the bushes to wait for the other two brothers who were to come later. When they arrived, all four Miniotis brothers cautiously proceeded to the place they had left the new boat, entered it and rowed through a devious route to Turkey. Back at the police station, the corporal, after sufficient delay, called his commander, the police sergeant Vassiliadis, a collaborator of the Germans, who was outraged. He ordered a search for the Miniotis brothers, and released all the other fishermen.

The whole police force then went to Nenita and searched the Miniotis family houses, not finding the fugitives. They then ordered the mayor, also a pro-German, to search the whole village, which he did to no avail.

In Çeşme, the Miniotis brothers were safe, but very worried about the families they had left behind.

Captivity

Sergeant Vassiliadis informed his German superior of the situation, and the German ordered the arrest of all the remaining Miniotis family members, in case the four brothers could not be found.

Two days after the four brothers disappeared, the Miniotis houses were surrounded at dawn and all the Miniotis family members were captured, 21 persons overall, including women, small children and old people. Only George Miniotis, the eldest son of Capt. Stamatis, managed to escape by jumping out of the window and hiding in the woods.

The captives were led to Kalamoti, where Capt. Stamatis’ wife Aphrodite was interrogated. They then were locked in a shed for the night.

The next day the captives started on foot for Chios Town, 22 kilometers away, where they arrived on nightfall. They were afraid their final destination would be Thessaloniki, to a concentration camp, or even Germany.

After a two-week stay in prison and more interrogations, the family was moved to Vrontadhos, just north of Chios Town, and detained at the local police station. Back at Nenita, George Miniotis left his hideout and contacted his maternal uncle, who fortunately had been not arrested. He then went to the beach and saw with relief that the new boat was missing, meaning that the four brothers had succeeded in escaping. There he also witnessed some villagers looting the family’s storehouse. He considered escaping himself with the smaller boat to bring the news to his father, but his uncle dissuaded him, afraid that the Germans had left the boat there as bait.

In Çeşme, Capt. Stamatis was preparing to return to learn about his family, but then John Papastefanou, the telephone company director, succeeded in connecting the Zymaris clinic phone with Çeşme to tell them the news.

While waiting for an opportunity to liberate his family, Cap. Stamatis resumed his voyages to the Dodecanese, visiting his friend the Cretan in Arki Island and coming back with information. He now used a new route, passing between Samos Island and Turkey and making an intermediate stop at cape Canapitsa, where there was a Turkish outpost.

Two days before Christmas 1941 the police sergeant of Vrontadhos surprisingly announced to the detained Miniotis family that they were free to go. The German commander had just set the condition that they had to appear twice a week at the Vrontadhos police station, to sign at the station book. It was unbelievable. Immediately, the family returned to their village Nenita, just in time for Christmas. The family continued their trips to Vrontadhos police station till the middle of March, only towards the end it was just once a week, and the children and older people were exempted.

Then, one night, there was a knock at the door. The Miniotis family understood that they had come to rescue them.

Indeed, it was Capt. Michalis Miniotis. Quickly, all family members were gathered and proceeded to a secluded beach, where they were picked up by a caique. After some suspense, when the caique’s motor suddenly stopped, they succeeded in starting it up again to finally reach Çeşme.

There the Miniotis family was safe. They were of course worried of the possibility that Turkey could enter the war at the side of the Axis, but for such an occasion they had one of the Giraud yachts, the “Lady May” ready, to carry them all to Cyprus.

The refugees

By June 1942 many people were escaping from Greece, especially seamen with their vessels, and most of them were ending up in Çeşme. The British Vice-Consul enlisted the most daring, and a small fleet was assembled.

Noel Rees rented Kioste, a small protected cove north of Çeşme, ostensibly for recreation purposes, and the fleet of caiques was relocated there.

Rees let Capt. Stamatis choose a better boat for his trips to the southern Aegean, and he selected the Vice-Consul’s own yacht, “Serena”, a petrol-engine vessel which had formerly belonged to the American Consul in Volos.

Capt. Stamatis and his crew of four, including his son George, was responsible for the Dodecanese, while other boats traveled all around the Aegean, to Piraeus, Thessaloniki, Volos, Lesbos Island etc.

The base at Kioste was set up to include machine repair facilities, a shipyard and storage areas. There was even a British pigeon trainer there, for the carrier pigeons most vessels had with them while on a mission.

The refugee stream to Turkey was steadily increasing, so that Çeşme had become a huge refugee camp. Able men were selected and sent to Egypt, to enlist in Greek regiments and fight for the Allies.

Cap. Stamatis continued his frequent voyages to Arki Island, now with the new ship whose trip was shorter. While at Çeşme, he was active at the refugee reception committee.

In the meantime, while the conditions in Greece deteriorated further, the general war situation gradually improved.

In January 1943, every day 100 to 200 refugees were arriving at Çeşme. One of these was the former police corporal of Kalamoti, Capt. Stamatis’ savior, who stayed for a while at Çeşme before moving on to Egypt.

One month later, the Turks informed Nikos Diamantaras, the British Vice-Consul’s second-in-command, that a load of refugees were stranded on Makri, a small Turkish island close to the mainland.

Capt. Stamatis undertook the task of rescuing them. He approached the island with the bigger of the two Giraud yachts the “Lady May”, towing two boats along. After some initial havoc, as the refugees had been on the island for 3-4 days without provisions and were already desperate, Capt. Stamatis succeeded in picking up all 345 of them on the yacht and the two small boats.

They had been left there because the seamen who carried them to Turkey were afraid to land on the Turkish mainland, and they had misled the refugees by not telling them they were being left on an island.

This situation continued till the end of the war. Twice a week, a boat from Çeşme traveled to Makri and collected any refugees left there.

The police sergeant

One day, during the registration of refugees in Çeşme, a familiar name cropped up: Vassiliadis. He was the police sergeant responsible for the trap set up to capture the Miniotis brothers.

At his interrogation by Nikos Diamantaras and Capt. Stamatis he recounted his story. After the disappearance of the rest of the Miniotis family, he was threatened by the German deputy commander, a cruel Nazi, that he and his family would suffer if he didn’t find out where they were hiding. Then, his own deputy, the patriotic corporal, disappeared. The sergeant realized that he would be in grave danger if this would become known.

So he arranged to escape, together with his wife. They, together with 20 others, boarded a small caique and tried to cross the sea to Turkey. Unfortunately the caique was an old wreck. Soon a hole appeared at its bottom and the boat started to sink. The police sergeant managed to grab a piece of wood, and soon afterwards he located his wife. Together they stayed afloat, while all the others were drowning. After a while they saw the light of the lighthouse on Paspargos, the small Turkish island at the Chios straits. Swimming the whole night they managed to reach the island. There they were later found by a Turco-Cretan, a resident of the village of Çiftlik, the former Kato Panaghia, the place of origin of the Miniotis family when they were still living in Asia Minor before 1922.

The couple was rescued and brought to Çeşme. After a while they were transferred to Egypt, where they were kept under surveillance.

Meanwhile, in Chios, the Germans suspected Papastefanou, the telephone company director, and two other of the resistance group members. On learning this, Capt. Stamatis arranged to pick them up and bring them to Çeşme.

After a while, a second naval base was established in Agrelia bay, south of Çeşme. The caique fleet was split in two, with most of the vessels moving to the bigger new base.

Capt. Stamatis also moved to Agrelia, and continued from there with the yacht “Serena” and his crew the trips to Arki Island in the Dodecanese.

Cape Canapitsa

In May 1943, on the return leg of one of the trips to Arki Island, the “Serena” had a mechanical problem. Capt. Stamatis, unsure if they could repair the engine, let free two carrier pigeons, informing their base they were near Cape Canapitsa. After a while the crew succeeded in repairing the engine and they continued to Canapitsa, where they paused as usually. Unfortunately, the sergeant of the Turkish outpost there had been changed, and the new sergeant, a German sympathizer, wanted trouble.

He ignored the voyage permit shown to him and ordered to empty the boat of all things it contained. That was of course impossible, because the ship was heavily armed. It carried machine guns, Tommy-guns, hand grenades, dynamite sticks, magnetic mines etc., all stuffed away in inconspicuous-looking places.

After Capt. Stamatis denied they had anything on board, the sergeant brought an adz and a saw and started searching. When he found nothing but some containers full of sand, he phoned his superior, the military commander of Kuşadası, and then ordered the boat to sail there under custody.

Once in Kuşadası Capt. Stamatis was summoned for interrogation by the pro-German commander, a captain, while the other crew members were locked up in a room. Capt. Stamatis declared he was an agent of Turkish Security, showing the captain a document to demonstrate it. Nonetheless the Turkish captain had him stripped naked and found a sealed envelope addressed to the head of Turkish Security in Smyrna, and containing information about the Dodecanese.

Fortunately, while the captain contemplated if he should open the envelope, Nikos Myristis, a Greek responsible for refugee relief in Kuşadası, arrived. Having seen the yacht “Serena” in the harbor, he was worried and rushed to the commander’s building, having first informed Nikos Diamantaras in Çeşme.

Some hours later, the British Vice-Consul arrived in Kuşadası, bringing with him Selahattin, the head of Turkish Security. The pro-German captain was reprimanded, and the “Serena” crew released.

After this event, Capt. Stamatis changed their route to Arki Island, passing between Samos and Ikaria Islands instead of Cape Canapitsa. Later, they heard that the two pro-German Turks, the sergeant and the captain, were sent to Ankara and sentenced to prison for disobedience and not acknowledging official documents.

Arki Island

In the summer of 1943, Capt. Stamatis continued his visits to Arki Island. Once, they arrived there in the middle of the night, in the secluded cove where they usually met the Cretan, but he was not present. They decided to go to his home, just over a hill, to find out what was happening.

Capt. Stamatis took with him the other two crew members, but left his son George, fully armed, by the hidden ship. He told him to wait for half an hour and leave if they did not return. Should an Italian patrol appear, he was to shoot them, board the ship, which could be operated but just one man, and return to their base. George waited in anguish in the dark of the night, looking around with his night-vision glasses and hearing the bells of the sheep, which were in the vicinity. In the meantime, Capt. Stamatis reached the Cretan’s house and found out why he hadn’t come to the rendezvous. Some Italians had visited him, and they were still in his house drinking and singing.

The “Serena” crew waited till the Italians left and then, together with the Cretan, his son and his older daughter, started to walk towards the ship. George expected to see three people returning, but suddenly he saw six shadows descending the hill. Thinking they were an Italian patrol, he was ready to shoot them. Only in the last moment did he hear them speaking in Greek to each other, and the tragedy was averted.

They returned safely to the base in Agrelia. More than 20 ships were now there, and at the shore there was a mini-market, a cafe for the seamen and two big storehouses, one for ammunition and supplies, the other for diesel fuel. The petrol was stored in a vessel in the middle of Agrelia bay.

On the return leg of another trip to Arki Island, George Miniotis with his glasses saw on the stern side of the ship a small red light. The crew maneuvered the boat to avoid a collision, because the light belonged to a large enemy destroyer on collision course. After a little while, they saw more red lights. They now were in the middle of an enemy convoy heading north. Capt. Stamatis quickly ordered his crew to also put on a red light, and in this way they succeeded in fooling the enemy ships that they also belonged to the convoy. Some time after they were left behind and they then made a sharp turn and vanished.

In July 1943 the Allies had invaded Sicily, which they quickly conquered. In September Italy capitulated, and after that some important Italian-held South Aegean islands, Kos, Leros and Samos among them, were occupied by British forces.

Fireworks

As Italy had capitulated, there was now no need to continue the usual information-collecting trips to Arki Island. Capt. Stamatis undertook a new mission, to regularly carry two British officers to British-held Samos Island and back.

In the late afternoon before one of the trips to Samos Island, the “Serena” crew waited for a new engineer, as their regular one had been ill. When he arrived, he tried to start the engine in order to approach the fuel ship in the middle of the bay, to load some petrol.

Unfortunately, the engine would not start. George Miniotis, who was on board with his younger brother Nikolis, told him to unscrew the spark plugs and warm them in the small kitchen stove, a common trick employed at the time with such primitive engines.

The engineer would not take advice from a 17-year old boy, so he told George to bring a petroleum lamp in order to see better, as the flashlight’s battery was exhausted. George protested vehemently, because it was too dangerous to bring an open flame in the vicinity of the petrol engine.

The engineer seemed to agree, and told George to go under the deck and check the fuel leads for leakage. George did it, but before he could come out, he heard an explosion.

In the meantime, the engineer had done what he originally intended, he brought the petroleum lamp near the engine and the petrol had caught fire. Soon the fuel tank exploded, with George trapped under the deck, and his hands, soaked with petrol, caught fire.

Until he succeeded coming up, he was all on fire. He at once jumped overboard, while screaming to his brother to do likewise. He heard three splashes, the engineer and the two crew members jumping into the sea.

On board was also the captain of the fuel supply ship. He calmly pulled the rope that had bound a smaller boat behind “Serena” and together with Nikolis, George’s brother, they entered the smaller boat and rowed to the shore. The “Serena” crew also safely swam to the shore, and only George had some scalds on his hands. “Serena” was now burning like a torch, and from time to time there where explosions, as the ammunition on board caught fire. For two hours, Agrelia bay was like hell. The next day there was nothing left of the yacht. Only its burned hull could be discerned at the bottom of the sea.

Capt. Stamatis received another yacht, “Nereia”, and with it he resumed carrying the two British officers to Samos Island. On the return trip they found and arrested on a small island just outside Samian port Vathy two German spies, posing as British soldiers.

Adrias

Capt. Stamatis next carried the same two British officers with a caique to Gümüşlük, a small bay near Bodrum in Turkey. There the crew saw the Greek destroyer “Adrias” stranded on the beach. What had happened?

George Miniotis, curious to know, rowed in a small boat near the ship, where he was called on board by an acquaintance of his he had known from Çeşme. His friend recounted to George the story of “Adrias”.

The destroyer patrolled near Kalymnos Island, when it was struck by a mine. The ship’s bow broke away and sunk, but the watertight wall was not punctured and “Adrias” managed to stay afloat. The companion ship, the British destroyer “HMS Hurworth”, came near to help, but it was also struck by a mine and sunk quickly, while hundreds of sailors drowned (the story of this twin disaster).

After collecting many British from the sea, including the ship’s captain, the bowless “Adrias” managed to reach this small Turkish bay, where it was stranded awaiting developments.

Capt. Stamatis and crew slept there for the night, but they were suddenly awakened. A small British transport ship had sunk near a reef to the south, and they quickly sailed there to collect any survivors.

It was a dangerous operation to approach the reef during the night, but they succeeded in collecting some 30 sailors, who had been holding on the half-sunk transporter. Fortunately before sinking they had managed to inform via wireless the base at Bodrum of their accident.

The Miniotis team carried the shipwrecked sailors back to Gümüşlük and awaited new orders.

The dogfight

The next day Capt. Stamatis had to forward the two officers to British-held Leros Island. Leros had been the main Italian bastion in the Dodecanese before Italy’s capitulation.

When they arrived at Aghia Marina bay the guard at the outpost recommended them to move to the opposite side of the bay, secure the vessel and go ashore, because the area would soon be bombarded by German aircraft (eyewitness account). They followed the advice and rowed with the small boat to the beach, where a jeep picked up the two officers to drive them to the British headquarters.