The Ottoman Period

The Ottomans, following the conquest of Istanbul (1453), did not encourage the export of goods. Sea routes were not safe yet and trade stil used the caravan routes. The few luxury goods reaching Izmir were directed from the Port of Cesme to the Island of Chios.

At the beginning of the XVI Century, Izmir was taking part in a stable and great empire but the port was not commercially important yet. In the 1500, cereals, fruits, beans and wax were shipped with Ottoman, Venetian and Genovese ships. The Venetians were quite strong in the Mediterranean in this period.

According to Elena Frangakis-Syrett (the Commerce of Smyrna), the growth of Izmir (Smyrna) as an important mercantile centre dates from the early sixteen century. This is owed to the establishment of the European Consulates in the city, and according to Daniel Goffman (Izmir and the Levantine World 1550 – 1650) was also due to the search of Dutch, English, French merchants for a new port in the Mediterranean. Izmir was preferred as it was not subject to the many rules and regulations that long established ports such as Aleppo were burdened with. Besides, cotton, an Izmir hinterland product, and by 1630, the Persian silk were the most important commodities available in Izmir.

In the middle of the XVII century, the Sublime Porte (the Ottoman government) put into an effect a policy of promoting Izmir as the exclusive port of the Western Anatolia to trade with the international market and accordingly went about to improve its infrastructures, docks, warehouses and customs houses.

The port that suffered due the Izmir’s rise was Chios and many Chiot merchant families which had considerable experience and excellent organization in the sea trade from the 1700’s began to install themselves in Izmir. These Chiots traders, shipowners, charterers with their own commercial houses in the most important Mediterranean ports, will, according to Gelina Harlaftis (the Chiot phases), attain by the end of the XVIIIth century, the number of 500 Chiot firms active in Izmir.

Due to its strong links with Western Europe, the port of Izmir having a return cargo had lower freight rates in comparison of other ports which could be even in nearest distance to the Syrian and Persian markets, such as the ports of Beirut and Iskenderun (Alexandretta).

Until the late 1700’s the Muslim and non-Muslim local merchants controlled the internal trade, while the Europeans monopolized to a large extent the import-export from the port of Izmir. The dominating countries were France and Great Britain followed by Holland. These countries created systems through their governments, chambers and consuls to enhance the conditions for their own trade, i.e. the famous Levant Company shadow of the Great Queen Elisabeth I of England and the powerful Chamber of Commerce of Marseille.

However a degree of cooperation with the local merchants was always necessary and the Ottoman merchants, the Chiots, the Greeks and the first Levantines1 were smart enough to cope with them. Their expert knowledge of the Ottoman market and their many contacts in the region gave them a versatility that the European merchants could not match writes the expert, Elena Frangakis-Syrett. In 1782, thirty Chiot merchants formed a league in order to strengthen their bargaining position with the Dutch importers of cloth, a commodity on which the Chiots were second to anyone. We see then in “the list of the merchants who took part in the trade of Smyrna with Holland carried out in Dutch ships 22 August 1786 to 26 February 1787”, a clear Chiot majority, comprising, those of Italian origin, Giustiniani, Negroponte, Baltazzi and of Byzantine-Greek origin, Mavrogordato, Schilizzi, Petrocochino, Ralli and many others.

By the end of the XVIII Century the French also found it profitable to cooperate instead of competing with the local merchants. The British also followed these examples and in 1797 the Ottomans obtained from the British government a reciprocal trade agreement.

Around the same period J. B. Giraud as merchant/ ship owner is trading with Marseille. In addition, rich Turks and Jews operated the custom house of Izmir. These custom officials were very influential men.

The Turks played their most important role as landowners and producers of cotton and wheat. Karaosmanoglu and Araboglu were producers of these important products and as well, local ayans, multezims (those who obtained the right for the collection of taxes) and administrators. I know from my family records that the Baltazzi’s were very close to the Karaosmanoglu’s from whom they also bought a lot of land.

By 1812, the world’s two major Merchant navies, the British and the Americans, controlled the Mediterranean Cargo Trade.

Elena Frangaki Syrett in her already mentioned book writes that by 1820 there were five Dutch commercial concerns that had enough capital to allow them to wait to intervene in the market at the best moment were trading in Smyrna. P. Vansanen, A. Slaars, D. Sponte, G. Hoeting & Co., the Van Lennep’s as well as Jacques Dutilh and his son Daniel. - [copy of the constitution of the Dutch Levant Company].

According to an anonymous American author, in the 1820’s, the chief U.S. imports from Smyrna were opium and drugs, madder, raw and manufactured silks and carpets.

Prof. Çinar Atay, in the book “Izmir”, mentions that the first regular commercial fleet from Europe to Izmir started in 1829 with the Aynard brothers.

During the year 1831, U.S. trade with Izmir had involved 27 ships with an import value of USD 3,5 million and export value of USD 8,0 million.

Some statistics of the period 1818-1839 shows that the main ports with which Izmir was trading were still the Mediterranean ones. However as the first ports start to be those of the U.K. with 23,66 % share, Trieste with 19,42 % second and Marseille with 12,95 % third, fourth the American ones with 8,96 % and Livorno with 5,47 % fifth. (Küçükkalay A.M.). It has to be considered that the ports of Trieste and Livorno were used also as entrepots for the European seatrade and were home of many Chiot families commercial houses.

The financial transactions, regarding to the seatrade were quite complexed and merit some thoughts. The European merchants in Izmir were dealing with bills of exchange and as the Ottoman piastre (kurus) was falling in relation to European currencies and banking was on informal basis, leading to speculation in bills of exchange that could be profitable but also risky. It is known that a merchant of this period in the sea trade had to take into account all possible venues of activity, speculative monetary and commodity trading.

It is related by some authors that many merchants of Izmir2 had so much capital that they involved themselves in the banking of Galata (the financial center of the Empire) and even granted credit to the Ottoman Government. I am not sure that this could apply to many in as far as cash flow is concerned, as the market of Izmir often ran short of money but had always credit and confidence from Europe.

Possibly in order to remediate to these uneasy financial conditions, the local British merchants in 1842 attempt to launch a bank in Izmir. “The Bank of Smyrna” under the protection of the Swedish Consul. However, as per the British Consulate records, there was the suspicion that the Galata Bankers and particularly the Baltazzi brothers opposed it and permission was not granted (1843). This information annoyed me, as I know that my ancestors, of whom many members stayed permanently since 1746 in Izmir and had a lot of interests, were very fond of this city as I am. I was therefore happy when I discovered what exactly happened related by the historian Hüseyin Al (Toplumsal Tarih, July 2000) who found in the Ottoman archives that a secret (the secrecy was I believe necessary to avoid further speculation) agreement was made in the same year of 1843 between the Ottoman government and Galata Bankers Jacques Alleon and Izmir born Emanuele Baltazzi for the stabilisation of the exchange rate to £1 = 110 Kuruş (piastres). With this agreement of a validity of 2 years the state also undertook to prevent during this time the establishment of any new bank by foreigners.

The agreement was successful and extended until 1849 when the first bank of the Empire, the Banque Constantinople, was officially opened with the same partners Baltazzi – Alleon. Without doubt this stabilisation was profitable to all the Empire’s economy including of course to the important sea trade of Izmir.

As from 1856, the banks of Istanbul starting with the Ottoman Bank and the main foreign banks which followed, opened branches in Izmir. They were also private credit institutions, bankers from members of the various communities, with the exception of the Muslim one as that religion did not permit such activity.

As it is mentioned by many economists, such as Aktar and Kıray, as from the second half of the XIX Century, the progresses made by the Ottoman Empire on the production of raw materials and manufactured goods influences principally the Port cities and the extension of their trade strengthens their position in the region as important trade centers. As raw materials Izmir was mainly exporting silk, mohair, yarn cotton and wool and as manufactured goods cloth and locally woven carpets which manufactured and exported in considerably increasing volumes. Furthermore with the increase of their population (In 1857, Izmir had about 180,000 inhabitants) these cities took a pre-eminent place in the Ottoman administrative structure.

The first railways of the Ottoman Empire, the Izmir – Aydın Railways (1860) and the Izmir-Kasaba (Turgutlu) Railways (1866) which the English had in concession were transferring the agricultural products of the hinterland to the port.

The famous camels caravans which were depicted in many engravings representing old Izmir were still in function servicing mainly from the hinterland to the railway stations and the port. The Quais tramways also assisted the transporting of merchandise in the evenings.

In 1875 Edward Baltazzi submitted a proposal to the Ottoman Government to operate vessels within and out the gulf creating a liaison with Karşıyaka, Menemen, Göztepe, Karataş, Urla, Foça, Çandarlı, Dikili, Ayvalık. The concession required was for 25 years and the flag would have been Ottoman. However as the Government was engaged to develop their Aziziye Company with similar projects, Baltazzi received a reply that a temporary permission without exclusive rights could be only granted and this until Aziziye starts its services. The two parts did not come then into an agreement and this project was not realized.

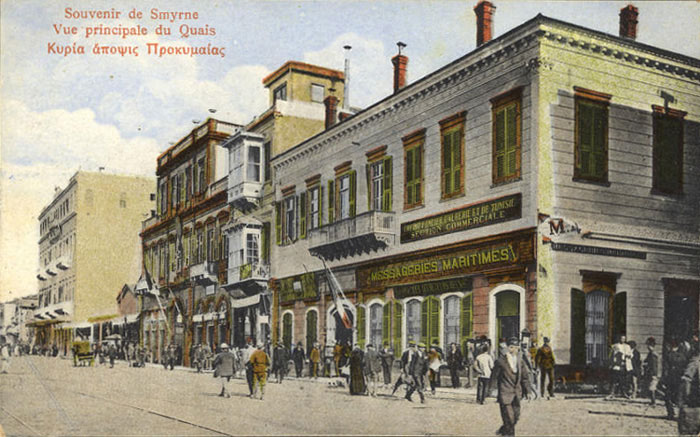

Finally the famous Quais of Izmir were terminated in 1876 by the French Dussault Brothers Company allowing high tonnage ships to dock.

Leon Kontente in his book “Smyrne et l’Occident” gives the following products statistics of 1881 for the port of Izmir. (Source: Georgiades Smyrne et l’Asie Mineure)

| Exports | Imports |

| Raisins 26,75 % | Cottons 26,42 % |

| Opium 14,31 % | Wool 8,23 % |

| Valonias 13,89 % | Cotton File 6,93 % |

| Figs 10,15 % | Coffee 5,49 % |

| Various 34,90 % | Various 52,83 % |

U.K. was holding the first place in Export as well as in Imports, followed by France.

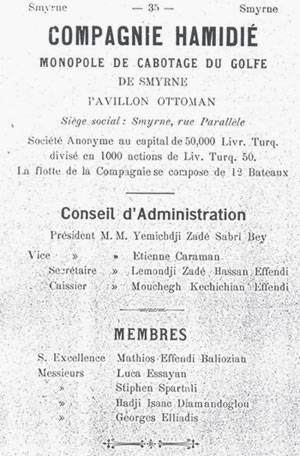

There were other proposals for the sea liaisons within the gulf, this of Uşakzade Sadik Bey and his partner Bergamalıyan as well as of Mahmut Celladedin Paşa, Zara Tahtayan and others. Finally Yahya Hayati Efendi obtained the concession and his Hamidiye Company starts in 1884 its services within the gulf. Jolly-Carmoly Company, which also had ships operating in the gulf, could not compete and sold its ships to Hamidiye.

I am indebted to my friend Bülent Şenocak (Levant’ın Yıldızı – Izmir) for the following information concerning the Izmir port traffic during this period.

| Inbound (number of ships) | Outbound (number of ships) | |||||

| Steamer | Sailing Ships | Steamer | Sailing Ships | Tonnage | ||

| 1863 | 592 | 956 | 590 | 1009 | 1862 | 302.771 |

| 1873 | 640 | 950 | 643 | 801 | 1863 | 507.800 |

| 1883 | 855 | 120 | 843 | 108 | 1886 | 1.340.000 |

| 1886 | 1299 | 102 | 1304 | 115 | 1887 | 1.537.812 |

| 1887 | 1316 | 282 | 1314 | 318 | 1888 | 1.581.001 |

| 1888 | 1385 | 373 | 1381 | 282 | ||

In the year 1890, there were 44 insurance companies in Izmir.

In 1893 the Belgians founded the Compagnie Ottomane des Eaux de Smyrne which improved the infrastructure of conveyance of water to the city and its neighbourhoods.

The Izmir – Aydin railways between the years 1897 – 1898 carried 299,000 tons of merchandise and 2.236,000 passengers and the Izmir – Kasaba (Turgutlu) line which became in 1893 a French concession was extended to Afyon in 1898.

As it is mentioned by Bülent Şenocak, all the above improvements including the telegraph lines put Izmir on a high level in as far as image and foreign relations are concerned and I may add influenced positively the sea trade and its components as well as the architectural and cultural physiognomy of the city with new types of hans, buildings, warehouses, bazaars, hotels, cafés, theatres, etc.

At the beginning of the XX Century in Izmir, the exportations attain 110.000,000 French francs in value. The importations were about half of this amount. Izmir secures 43% of all Ottoman exportations and 20% of all the importations. (Sources: Martal. A ve Kütükoğlu M.)

Gabriel J.B. Arcas established Arkas in 1902 as an import agency which later on began operations in the field of international transportation and shipping.

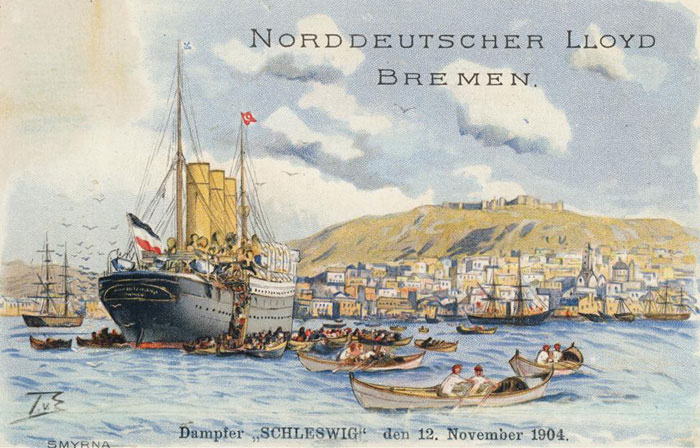

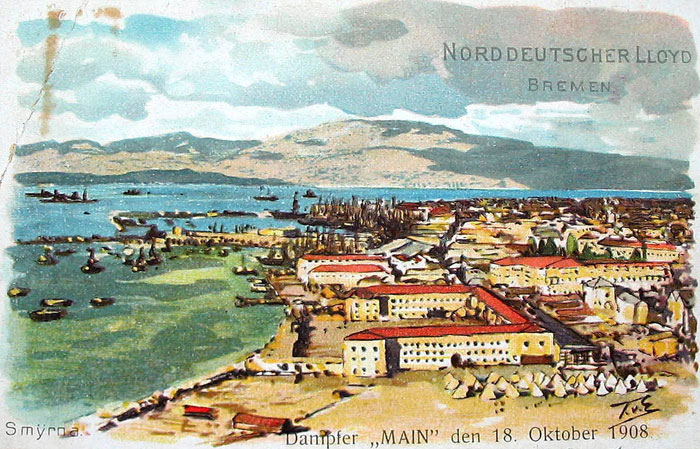

As relations with Germany intensified the German ships which in 1896, only accounted for 3,5% of the total tonnage in the Izmir maritime trade, reached 11,7% by 1908 and in sea trade Germany took, as far as tonnage is concerned, the fourth place behind UK, France, Greece.

According to the Izmir British Consulate records, in 1908, 2933 steamers with 2.743,823 tons and 4.347 sailing ships with 76.137 tons called at the Port of Izmir.

In the same year we see also in the import-export a growing interest from Italy which came third after U.K. and Austria-Hungary with the amount of 431.575 Lstg importations to Izmir and 313.079 Lstg exportations from our city.

In 1909 Izmir population was close to 300.000 inhabitants.

At the beginning of the XXth Century, there were 17 passenger lines, including the Hamidiye, already mentioned which owned 12 ships and also called to the distant ports of Urla, Foça, Karaburun, Ayvalık, Edremit and Mytilini.

Piers of Izmir

Rauf Beyru in his 19 Yüzyılda İzmir Kenti (The City of Izmir in the XIXth century) mentions in his article ‘Sea Transportation in Izmir’:

In the first half of the XIXth century before the introduction of steamers, Smyrna being a coastal city in close relation with the sea, sea transportation by tenders and kayıks had great importance. They were carrying goods from ships anchored in the gulf and many traders living and owning warehouses close the sea-front built private piers for this purpose.

In his research on the Frank Quarter Beyru lists the piers starting from the former St Pierre Castle (Liman Kalesi) going North as follows:

1- Saman İskelesi (Hay Pier)

2- Maltizlar İskelesi (Maltese pier)

3- Holland Pier

4- English Pier (close to the British consulate)

5- Baltazzi Pier

6- Fasoula Pier (close the French Consulate)

7- The New Pier (Yeni İskele) close to Gündoğdu

8 - Uzak İskele (the distant pier). Close the Punta.

However as from the very precious info from Bernadette Weiner we know that in 1864 the Baltazzi Pier was close to the old French Consulate and also had its own Café. The new French Consulate still standing was build in 1906 in its current location. We also know that Cafes were built-in to these Piers which would had been built as the later construction of quay and harbour facilities to cope with the increase of shipping traffic, made these piers somewhat redundant giving them new life as places of recreation and sometimes with tragic consequences when they collapsed (an example) and minimizing their importance as far as transport of goods is concerned.

|

|

|

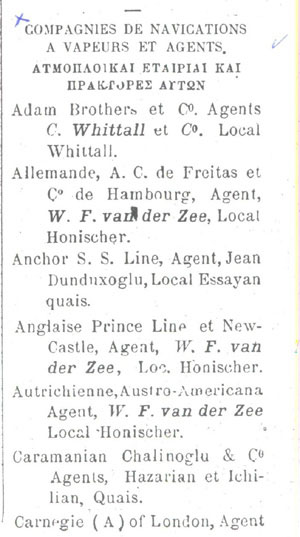

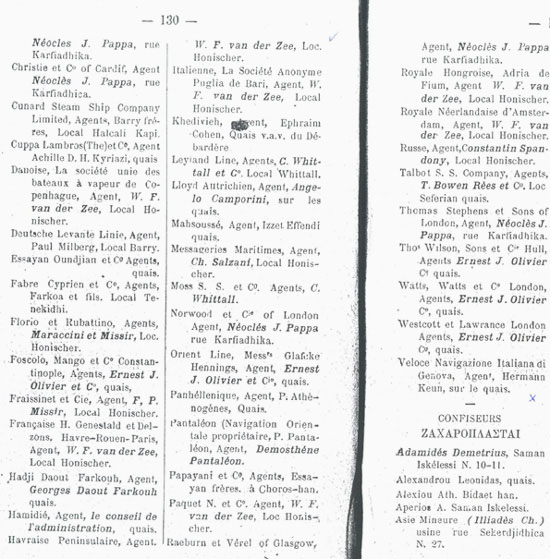

| PASSENGER LINES EX / TO IZMIR FROM EUROPE | |||

| Passenger Line | Flag | Izmir Agents | Source |

| Austrian Lloyd (until 1919) Lloyd Triestino (as from 1919) |

Austrian Italian |

Angelo Camporini Pier Dorsharmet |

Indicateur Commercial 1898-993 Commercial Guide 1920 |

| Navigazione Generale Italiana (Soc. Florio & Rubattino) | Italian | Maraccini & Missir | Indicateur Commercial 1898-99 |

| Deutsche Levante Line | German | Paul Milberg | Indicateur Commercial 1898-99 |

| A.C. de Freitas | German | W.F. Van Der Zee | Indicateur Commercial 1898-99 |

| Fraissinet and Co. | French | F.P. Missir | Indicateur Commercial 1898-99 |

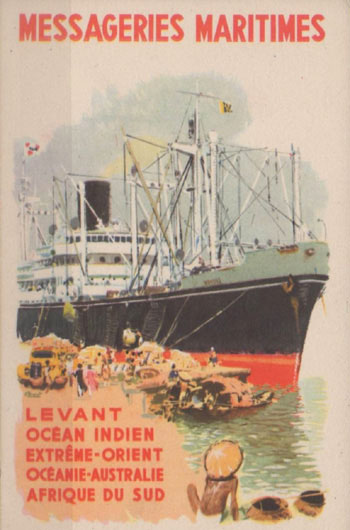

| Messageries Maritime | French | C.H. Salzani | Indicateur Commercial 1898-99 |

| Royal Netherlands Co. | Holland | W.F. Van Der Zee | Indicateur Commercial 1898-99 |

| Hadji Davut Farkouh Pass. Line (Syrian origin well-known shipowner) | Ottoman | George Davut Farkouh | Indicateur Commercial 1898-99 |

| Khediveh Egyptian Line | Egypt | Efraim Cohen | Indicateur Commercial 1898-99 |

| Russian Navigation | Russian | Constantin Spandony | Indicateur Commercial 1898-99 |

| Pan Hellenic Company | Greek | Athenogenis | Indicateur Commercial 1898-99 |

| Pantaleon Oriental Navigation | Greek | Demostene Pantaleon | Indicateur Commercial 1898-99 |

| Stamatiadi Company | Greek | Beginning XX Century - SmirniTa Nea Publ. 2002, Ref: A.M.A.E. | |

| Anatolia Company | Greek | ||

| Service Maritime Roumain | Romanian | ||

| Bulgarian Maritime | Bulgarian | ||

|

|

|

|

|

In 1913, the Izmir – Kasaba line carried 430,000 tons merchandise and 3,000,000 passengers (Issawi).

In this multiethnic and multicultural world of the port city of Izmir although communities were segregated with their inhabitations mostly in separate quarters, they had daily business relations between themselves. The Italo-Levantine writer Willy Sperco in his book “Turcs D’Hier et D’Aujourdhui” gives a colorful picture of this fact.

| The Turk Ali Ağa, producer was selling to Mr Whitemore, the English exporter, with the intermediary of Mr Cohen, an Ottoman Jew, cereals and raisins which were shipped by Sior Mifsod, a Maltese on Holland ships whose agent Sperco was Italian. The insurer Serafin was an Armenian and the banker who provided credit for this operation was Greek!! |

1 Levantine: Although it has been never been an official identity, we can consider Levantine, as many authors did, the second and subsequent generations of foreigners, who were born within the borders of the Ottoman Empire.

2 Families in both cities, Izmir & Istanbul, those I retraced as merchants in Izmir & bankers in Istanbul: the Chiots: Baltazzi, Negroponte, Pasquali, Mavrogordato, Schilizzi, Rodocanachi, Ralli, Vlasto. The English-Levantines: Edwards, Barker, Wilkin, Hanson. Others: Alberti, Caporal.

3 To view samples pages of the archive Smyrna trade registry, Indicateur Commercial of 1898-1899, click here.

4 A book published in 2000, ‘Négoce, ports et océans 16e-20e siècles [Trade, ports and oceans 16th-20th centuries], Silvia Marzagalli, Paul Butel, Hubert Bonin’, examines in detail the shipping networks of the Mediterranean, including those stretching from Marseille to Chios - Smyrna where the Baltazzis amongst others play key roles in their development - view details:

Alex Baltazzi, 2008