NAMIK KEMAL IN LONDON

Patriot, founder of the movement which became the Young Turks, poet, playwright, journalist, historian, novelist, exile, prisoner, four times provincial governor, Namık Kemal also crammed over two years’ residence in London into his short life. His great-great-grandson Osman Streater describes his stay, and sums up what makes him such a pivotal person in the development of modern Turkey.

From spring 1868 to summer 1870 my great-great-grandfather Namık Kemal lived in London. He rented a spacious apartment at 15 Fitzroy Square in Bloomsbury. From there, he was able to walk to 4 Rupert Street in Soho, where in June 1868 he began publication of the Young Ottoman newspaper Hürriyet.

Born in 1840, Namık Kemal only lived until 1888, but managed to pack a huge amount into those years by being an early starter in most things. He wrote his first beyt or rhyming couplet at 13. At 17 he married and entered the Translation Bureau of the Porte. In 1863 he became a journalist on Tasvir-I Efkâr, while keeping up his prolific writing elsewhere.

In the summer of 1865 he took part in an event took which was to affect the whole of the subsequent history of Turkey. The event in question cannot have looked particularly momentous to passers-by: it was a picnic in the Belgrade Forest near Istanbul. Taking part were six young intellectuals, some of whom, like Namık Kemal, worked in the Translation Bureau – and all of whom believed passionately that the Tanzimat or Reform movement started by the Imperial Rescripts of 1839 and 1856 had become bogged down. Two court officials, Âli Pasa and Fuad Pasa, were monopolising power, every now and then swapping the positions of Grand Vezir and Foreign Minister. What was needed, the picnickers decided, was real reform: constitutional reform, representational reform, reform carried out for Ottomans by Ottomans. During that picnic they founded a secret society. Originally called the Patriotic Alliance, it soon became known as the Young Ottomans. It rapidly set to work. In the judgment of the leading historian Şerif Mardin, ‘There is hardly a single area of modernisation in Turkey today, from the simplification of the written language to the idea of fundamental civil liberties, that does not take its roots in the pioneering work of the Young Ottomans.’

The Young Ottomans are usually regarded as Turkey’s first political party, even though they had no offices or branches, and published no manifesto. Nothing like them had ever happened before. The very concept of having an opinion had been unheard of. Once in their early days, when they were being rowed across the Bosphorus, a storm blew up. Namık Kemal looked worried. One of the Young Ottomans, Hikmet, said sarcastically to him: ‘So, Kemal, you look like you’re afraid of losing your precious life’. ‘It’s not my precious life I’m worried about,’ replied Namık Kemal. ‘If we drown, Ottoman public opinion drowns with us.’

The Young Ottomans were revolutionary for their times. However, they worked for reform along Islamic lines. By 1889, the year after Namık Kemal’s death, this was no longer enough. Thus it was that four young medical students – their less bookish background marks their different approach - founded the Young Turks. The Young Turks moved on from pan-Ottoman patriotism to overtly Turkish nationalism. They also watered down Islamic associations. After this came the final link in the chain leading to the present: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who brought the Empire to an end, created the Turkish Republic, and with his secular approach turned his back on Islam.

What was Namık Kemal’s role in all this? Has it any permanent historical significance? In the words of Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoglu, speaking of the legacy of other famous Ottoman poets: ‘If there hadn’t been a Şeyh Galib, or a Nedim, or even a Baki, or even a Fuzuli, Turkish literature today would be exactly the same. But without Namık Kemal we couldn’t had had modern Turkish literature, without Namık Kemal it is very hard to imagine how reforming Turkish thought could have got started.’

Namık Kemal introduced Turks to two concepts which were entirely new to them: freedom and patriotism. Before Namık Kemal wrote about it, the word ‘Hürriyet’ meant no more than technically not being a slave. After they had read his explanation of what freedom entailed, Turks realised for the first time that they had rights to fight for. Even more timely was his introduction of the concept of ‘Vatan’ or fatherland, where he did for Turkey very much what Renan did for France with the notion of la Patrie. Before Namık Kemal, the general assumption had been that Turkey was the personal property of the Sultan, and looking after it was his problem. After him, as Mustafa Kemal commented on being congratulated on his military victories in 1922: ‘the man who taught the young men of this generation that the independence and freedom of their fatherland are worth dying for was Namık Kemal’.

Back to 1865. The Young Ottomans were soon achieving a great deal of notice. By March 1867 Namık Kemal’s journalistic activities had begun seriously to annoy the administration. The fact that he was by now, aged 27, editing Tasvir-I Efkâr as well as writing revolutionary articles in it did not help. He was therefore appointed deputy governor of Erzurum. Therefore? Why therefore? There is an explanation.

The explanation is that Namık Kemal was of good family. His great-great-great-grandfather Topal Osman Pasa (1645-1735) had been Grand Vezir to Sultan Ahmed III. As a sign of favour, the Sultan had given one of his daughters, Küçük Ayşe Sultan, in marriage to Topal Osman’s son Ahmed Ratip Pasa. Namık Kemal was descended from their son Müderris Osman Pasa. His own father Mustafa Asım Bey was the Court Astrologer to Sultan Abdul Aziz, a man who rarely acted without consulting the runes. In those days, this kind of thing counted. Even amongst the Young Ottomans, revolutionary though they were, there were clear distinctions between those who were Bey and those who were merely Efendi.

This background flummoxed the authorities. Since the destruction of the Janissaries in 1826 they had enjoyed a life free of internal opposition. That is should now come from someone of good family, whose father the Sultan consulted on an almost daily basis, really threw them. This led to two totally opposite views on how to deal with Namık Kemal. Sometimes, the view prevailed that what he needed was punishment, and he was duly punished. But then the opposite view would arise, that he was ‘one of us’, and that all he needed to come to his senses was to be given a job with authority. On one occasion, he went from one extreme to the other in the same place: having been exiled to Mytilene in 1877, in 1879 he moved into the governor’s mansion on the island on being elevated to Mutasarrıf.

At any rate, early in 1867 he was in trouble in Istanbul. He had no intention of taking up his appointment in Erzurum. While he procrastinated, the invitation came from his patron Mustafa Fazıl Paşa to join him in Paris. Mustafa Fazıl had missed out on becoming Khedive of Egypt because another woman in the busy Khedivial harem had given birth to his half brother Ismail 40 days before him. He was rich and enjoyed making trouble. On May 17, Namık Kemal and his fellow Young Ottoman Ziya, the future famous Ziya Pasa, embarked secretly on a French vessel in the Golden Horn, meeting up en route with a third colleague, Ali Suavi Efendi. This was done with the help of the French ambassador in Istanbul, Bourrée. Within a few weeks, the French authorities were to take a very different attitude towards them.

By an extraordinary coincidence, on June 29 the Ottoman imperial yacht Sultaniye arrived in Toulon harbour carrying Sultan Abdul Aziz on the first ever state visit abroad by an Ottoman Sultan. His ambassador in Paris, Mehmed Cemil Pasa, had anticipated his arrival by having a quiet word with the French police. This resulted in their telling the Young Ottomans to leave France for the duration of the Sultan’s visit. Namık Kemal, together with three others, crossed the Channel and arrived in London.

Namık Kemal immediately took to London, even though, in common with all the other products of the Translation Bureau, he spoke French but no English. He felt at home in the Reading Room of the British Museum. He was impressed by the sheer modernity of the Britain of the day. He liked what he saw of British democracy, and in July 1867, with Parliament kept on at Westminster to pass the great Reform Bill, there was quite a lot to see. Best of all, he liked the atmosphere of freedom, of which he soon had personal evidence. For on July 10 Abdul Aziz was conveyed across the Channel on the French imperial yacht and started a state visit to Britain. But this time, there was no invitation from the British police to leave the country. Ziya decided to use the state visit secretly to send the Sultan a petition seeking to excuse his defection. Namık Kemal led the other two to have a look at Abdul Aziz when he went to Crystal Palace for a firework display in his honour. The Sultan, too, was curious. Noticing the three red fezzes amongst all the top hats, he whispered to his Foreign Minister Fuad Pasa: ‘Bunlar kim?’ – ‘Who are those people?’ Fuad, who knew Namık Kemal from the Translation Bureau, was able to enlighten him. The Sultan’s reaction is not recorded, but Namık Kemal’s is: he wrote that, having had to escape from Istanbul, and having been ordered out of France, that moment at Crystal Palace, when he was every bit as free as the Sultan, showed him for the first time the full meaning of freedom.

Abdul Aziz received the full treatment during his State Visit. Queen Victoria came out of the mourning she had been in since Prince Albert’s death in December 1861 for long enough to make him a Knight of the Garter at Windsor. She even kissed his eleven year old son Yusuf Izzeddin. But soon it was over, and Namık Kemal and his party went back to Paris, leaving Suavi in London to start publishing the first Young Ottoman overseas newspaper Muhbir. This soon started causing concern not just to the government in Istanbul but to the Young Ottomans in Paris because of its increasingly violent tone. In spring 1868, Mustafa Fazıl withdrew its funds and stopped publication, at the same time instructing Namık Kemal and Ziya to move to London to start a more moderate newspaper, Hürriyet.

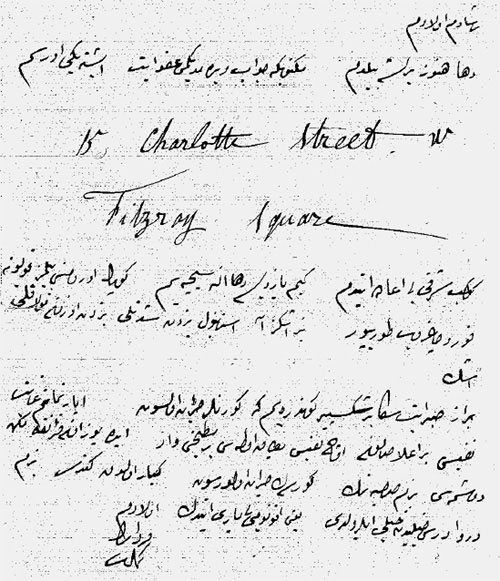

Soon Namık Kemal was writing to his friend Kayazâde Resad: ‘Here is my new address: Charlotte Street W., 15 Fitzroy Square. My apartment is magnificent. It has a fine drawing room, three splendid bedrooms and a kitchen. It costs one hundred and ten Francs a month, but the furniture belongs to the landlady. You would be impressed if you saw it. Haven’t we become genteel. My lessons in law are progressing.’

These lessons in law were in French – Namık Kemal wrote druva, an approximation to the French word droit. They came from a part journalist, part businessman Frenchman named H. (or A.) Fanton, who was secretary of the Société Français de Secours, with offices around the corner at 28 Grafton Street. We do not know how he met Fanton, but he proved to be a good friend and host as well as teacher. He would invite Namık Kemal to his house to see some of the family life he was missing – he must have left his wife in Istanbul just pregnant, for his son Ali Kemal was born at this time – and also some notable guests, among them the Pre-Raphaelite painter Holman Hunt. He also mentions a mysterious ‘companion of the soul’ with whom he would walk in Hyde Park. That seems to be as far as it went: ‘London is a big garden,’ he wrote to his father, ‘full of fruit. But its very abundance makes it less desirable, at least to me. My friends will confirm this. I live like an angel. A very chaste, very constant chap is what I am.’

The first edition of Hürriyet came off the Rupert Street printing press on June 29 1868. It soon led to dissension amongst the Young Ottomans, with some finding it too critical of the government and others not critical enough. But it was not slow to make an impact in Turkey, with issues being smuggled in and changing hands for high prices. While articles by other Young Ottomans, notably Ziya, were more personal in their attacks on government figures, Namık Kemal’s writings became the main attraction because they addressed more fundamental issues. Niyazi Berkes, in his classic work The Development of Secularism in Turkey, has described Namık Kemal’s eight Letters on the Constitutional System published in Hürriyet during September-November 1868 as ‘the first attempt to explain to Turkish readers the theory underlying liberalism and constitutionalism’.

Meanwhile, the Sublime Porte had come up with an interesting offer: it would itself take two thousand copies of each issue from London, provided that the paper toned down its criticism. Ziya immediately rushed out an article with the headline ‘Yaşasın Sultan Aziz, Bravo Bâb-I Âli!’ (‘Long live Sultan Aziz, Bravo Sublime Porte!’ Perhaps this made the Porte suspicious of being taken seriously, for no money ever arrived. However, Ziya eventually accepted a subsidy from the Khedive of Egypt, Ismail, who wished the paper to use the opening of the Suez Canal to emphasise his independence from Istanbul. Namık Kemal disagreed with this, and gave up his involvement with Hürriyet on September 6 1869, leaving Ziya to carry on as sole editor. The paper became increasingly polemical, finally going too far when Ziya published an article by Suavi suggested that the simplest way of removing the Grand Vezir Âli Pasa would be to assassinate him. When the Porte protested to the British government, which then started a law suit, both Ziya and Hürriyet fled to Geneva. The paper did not last long. However, the name lingered in folk memory, and Sedat Semavi did well to call the now very successful newspaper which he started in May 1951 Hürriyet.

Namık Kemal stayed on at Fitzroy Square for several months. With the help of his friend Fanton, he was supervising the printing of a special edition of the Koran for Mustafa Fazıl Pasa. In July 1870, on the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, he moved to Belgium. Here he received, in what must have been a concerted action, letters urging him to return to Istanbul and assuring him of his safety. They came from the chief of police Hüseyin Hüsnü Paşa, the private secretary to the Grand Vezir Âli Pasa, and Halil Şerif Paşa, ambassador in Vienna and son-in-law of Mustafa Fazıl. Halil Serif added an invitation to stay with him in Vienna on the way. It took another three months to persuade him, but in October Namık Kemal was in Vienna. On November 22, he finally arrived back in Istanbul. His family were at Sirkeci station to greet him.

His life soon resumed its extraordinary mixture of activities. While turning increasingly to writing plays, he also resumed his journalism. In July 1872 he became editor of the newspaper İbret, only to find himself appointed governor of Gallipoli three months later. Dismissed from his governorship in March 1873, he arrived back in Istanbul just in time for the first performance of his defining patriotic play Vatan Yahut Silistre (The Fatherland or Silistria). The enthusiastic applause brought the house down, but also brought down on his head the wrath of the authorities, who imprisoned him in Cyprus in the prison which is still preserved as a museum dedicated to him. Released, and then again exiled, he made a speciality of the Greek islands. First exiled to and then governor of Mytilene, he then moved to Rhodes as governor. It was there that he gave his blessing to the marriage of my great-grandparents: Menemenlizâde Rifat Bey, a civil servant, had been sent to keep an eye on him, but had instead fallen under Namık Kemal’s spell and in love with his daughter Feride. Increasingly unwell, he turned in his last period of life to writing a history of the Ottoman Empire. He died in the governor’s mansion on Chios of a lung disease on December 2 1888.

Osman Streater

Patriot, founder of the movement which became the Young Turks, poet, playwright, journalist, historian, novelist, exile, prisoner, four times provincial governor, Namık Kemal also crammed over two years’ residence in London into his short life. His great-great-grandson Osman Streater describes his stay, and sums up what makes him such a pivotal person in the development of modern Turkey.

From spring 1868 to summer 1870 my great-great-grandfather Namık Kemal lived in London. He rented a spacious apartment at 15 Fitzroy Square in Bloomsbury. From there, he was able to walk to 4 Rupert Street in Soho, where in June 1868 he began publication of the Young Ottoman newspaper Hürriyet.

Born in 1840, Namık Kemal only lived until 1888, but managed to pack a huge amount into those years by being an early starter in most things. He wrote his first beyt or rhyming couplet at 13. At 17 he married and entered the Translation Bureau of the Porte. In 1863 he became a journalist on Tasvir-I Efkâr, while keeping up his prolific writing elsewhere.

In the summer of 1865 he took part in an event took which was to affect the whole of the subsequent history of Turkey. The event in question cannot have looked particularly momentous to passers-by: it was a picnic in the Belgrade Forest near Istanbul. Taking part were six young intellectuals, some of whom, like Namık Kemal, worked in the Translation Bureau – and all of whom believed passionately that the Tanzimat or Reform movement started by the Imperial Rescripts of 1839 and 1856 had become bogged down. Two court officials, Âli Pasa and Fuad Pasa, were monopolising power, every now and then swapping the positions of Grand Vezir and Foreign Minister. What was needed, the picnickers decided, was real reform: constitutional reform, representational reform, reform carried out for Ottomans by Ottomans. During that picnic they founded a secret society. Originally called the Patriotic Alliance, it soon became known as the Young Ottomans. It rapidly set to work. In the judgment of the leading historian Şerif Mardin, ‘There is hardly a single area of modernisation in Turkey today, from the simplification of the written language to the idea of fundamental civil liberties, that does not take its roots in the pioneering work of the Young Ottomans.’

The Young Ottomans are usually regarded as Turkey’s first political party, even though they had no offices or branches, and published no manifesto. Nothing like them had ever happened before. The very concept of having an opinion had been unheard of. Once in their early days, when they were being rowed across the Bosphorus, a storm blew up. Namık Kemal looked worried. One of the Young Ottomans, Hikmet, said sarcastically to him: ‘So, Kemal, you look like you’re afraid of losing your precious life’. ‘It’s not my precious life I’m worried about,’ replied Namık Kemal. ‘If we drown, Ottoman public opinion drowns with us.’

The Young Ottomans were revolutionary for their times. However, they worked for reform along Islamic lines. By 1889, the year after Namık Kemal’s death, this was no longer enough. Thus it was that four young medical students – their less bookish background marks their different approach - founded the Young Turks. The Young Turks moved on from pan-Ottoman patriotism to overtly Turkish nationalism. They also watered down Islamic associations. After this came the final link in the chain leading to the present: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who brought the Empire to an end, created the Turkish Republic, and with his secular approach turned his back on Islam.

What was Namık Kemal’s role in all this? Has it any permanent historical significance? In the words of Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoglu, speaking of the legacy of other famous Ottoman poets: ‘If there hadn’t been a Şeyh Galib, or a Nedim, or even a Baki, or even a Fuzuli, Turkish literature today would be exactly the same. But without Namık Kemal we couldn’t had had modern Turkish literature, without Namık Kemal it is very hard to imagine how reforming Turkish thought could have got started.’

Namık Kemal introduced Turks to two concepts which were entirely new to them: freedom and patriotism. Before Namık Kemal wrote about it, the word ‘Hürriyet’ meant no more than technically not being a slave. After they had read his explanation of what freedom entailed, Turks realised for the first time that they had rights to fight for. Even more timely was his introduction of the concept of ‘Vatan’ or fatherland, where he did for Turkey very much what Renan did for France with the notion of la Patrie. Before Namık Kemal, the general assumption had been that Turkey was the personal property of the Sultan, and looking after it was his problem. After him, as Mustafa Kemal commented on being congratulated on his military victories in 1922: ‘the man who taught the young men of this generation that the independence and freedom of their fatherland are worth dying for was Namık Kemal’.

Back to 1865. The Young Ottomans were soon achieving a great deal of notice. By March 1867 Namık Kemal’s journalistic activities had begun seriously to annoy the administration. The fact that he was by now, aged 27, editing Tasvir-I Efkâr as well as writing revolutionary articles in it did not help. He was therefore appointed deputy governor of Erzurum. Therefore? Why therefore? There is an explanation.

The explanation is that Namık Kemal was of good family. His great-great-great-grandfather Topal Osman Pasa (1645-1735) had been Grand Vezir to Sultan Ahmed III. As a sign of favour, the Sultan had given one of his daughters, Küçük Ayşe Sultan, in marriage to Topal Osman’s son Ahmed Ratip Pasa. Namık Kemal was descended from their son Müderris Osman Pasa. His own father Mustafa Asım Bey was the Court Astrologer to Sultan Abdul Aziz, a man who rarely acted without consulting the runes. In those days, this kind of thing counted. Even amongst the Young Ottomans, revolutionary though they were, there were clear distinctions between those who were Bey and those who were merely Efendi.

This background flummoxed the authorities. Since the destruction of the Janissaries in 1826 they had enjoyed a life free of internal opposition. That is should now come from someone of good family, whose father the Sultan consulted on an almost daily basis, really threw them. This led to two totally opposite views on how to deal with Namık Kemal. Sometimes, the view prevailed that what he needed was punishment, and he was duly punished. But then the opposite view would arise, that he was ‘one of us’, and that all he needed to come to his senses was to be given a job with authority. On one occasion, he went from one extreme to the other in the same place: having been exiled to Mytilene in 1877, in 1879 he moved into the governor’s mansion on the island on being elevated to Mutasarrıf.

At any rate, early in 1867 he was in trouble in Istanbul. He had no intention of taking up his appointment in Erzurum. While he procrastinated, the invitation came from his patron Mustafa Fazıl Paşa to join him in Paris. Mustafa Fazıl had missed out on becoming Khedive of Egypt because another woman in the busy Khedivial harem had given birth to his half brother Ismail 40 days before him. He was rich and enjoyed making trouble. On May 17, Namık Kemal and his fellow Young Ottoman Ziya, the future famous Ziya Pasa, embarked secretly on a French vessel in the Golden Horn, meeting up en route with a third colleague, Ali Suavi Efendi. This was done with the help of the French ambassador in Istanbul, Bourrée. Within a few weeks, the French authorities were to take a very different attitude towards them.

By an extraordinary coincidence, on June 29 the Ottoman imperial yacht Sultaniye arrived in Toulon harbour carrying Sultan Abdul Aziz on the first ever state visit abroad by an Ottoman Sultan. His ambassador in Paris, Mehmed Cemil Pasa, had anticipated his arrival by having a quiet word with the French police. This resulted in their telling the Young Ottomans to leave France for the duration of the Sultan’s visit. Namık Kemal, together with three others, crossed the Channel and arrived in London.

Namık Kemal immediately took to London, even though, in common with all the other products of the Translation Bureau, he spoke French but no English. He felt at home in the Reading Room of the British Museum. He was impressed by the sheer modernity of the Britain of the day. He liked what he saw of British democracy, and in July 1867, with Parliament kept on at Westminster to pass the great Reform Bill, there was quite a lot to see. Best of all, he liked the atmosphere of freedom, of which he soon had personal evidence. For on July 10 Abdul Aziz was conveyed across the Channel on the French imperial yacht and started a state visit to Britain. But this time, there was no invitation from the British police to leave the country. Ziya decided to use the state visit secretly to send the Sultan a petition seeking to excuse his defection. Namık Kemal led the other two to have a look at Abdul Aziz when he went to Crystal Palace for a firework display in his honour. The Sultan, too, was curious. Noticing the three red fezzes amongst all the top hats, he whispered to his Foreign Minister Fuad Pasa: ‘Bunlar kim?’ – ‘Who are those people?’ Fuad, who knew Namık Kemal from the Translation Bureau, was able to enlighten him. The Sultan’s reaction is not recorded, but Namık Kemal’s is: he wrote that, having had to escape from Istanbul, and having been ordered out of France, that moment at Crystal Palace, when he was every bit as free as the Sultan, showed him for the first time the full meaning of freedom.

Abdul Aziz received the full treatment during his State Visit. Queen Victoria came out of the mourning she had been in since Prince Albert’s death in December 1861 for long enough to make him a Knight of the Garter at Windsor. She even kissed his eleven year old son Yusuf Izzeddin. But soon it was over, and Namık Kemal and his party went back to Paris, leaving Suavi in London to start publishing the first Young Ottoman overseas newspaper Muhbir. This soon started causing concern not just to the government in Istanbul but to the Young Ottomans in Paris because of its increasingly violent tone. In spring 1868, Mustafa Fazıl withdrew its funds and stopped publication, at the same time instructing Namık Kemal and Ziya to move to London to start a more moderate newspaper, Hürriyet.

Soon Namık Kemal was writing to his friend Kayazâde Resad: ‘Here is my new address: Charlotte Street W., 15 Fitzroy Square. My apartment is magnificent. It has a fine drawing room, three splendid bedrooms and a kitchen. It costs one hundred and ten Francs a month, but the furniture belongs to the landlady. You would be impressed if you saw it. Haven’t we become genteel. My lessons in law are progressing.’

These lessons in law were in French – Namık Kemal wrote druva, an approximation to the French word droit. They came from a part journalist, part businessman Frenchman named H. (or A.) Fanton, who was secretary of the Société Français de Secours, with offices around the corner at 28 Grafton Street. We do not know how he met Fanton, but he proved to be a good friend and host as well as teacher. He would invite Namık Kemal to his house to see some of the family life he was missing – he must have left his wife in Istanbul just pregnant, for his son Ali Kemal was born at this time – and also some notable guests, among them the Pre-Raphaelite painter Holman Hunt. He also mentions a mysterious ‘companion of the soul’ with whom he would walk in Hyde Park. That seems to be as far as it went: ‘London is a big garden,’ he wrote to his father, ‘full of fruit. But its very abundance makes it less desirable, at least to me. My friends will confirm this. I live like an angel. A very chaste, very constant chap is what I am.’

The first edition of Hürriyet came off the Rupert Street printing press on June 29 1868. It soon led to dissension amongst the Young Ottomans, with some finding it too critical of the government and others not critical enough. But it was not slow to make an impact in Turkey, with issues being smuggled in and changing hands for high prices. While articles by other Young Ottomans, notably Ziya, were more personal in their attacks on government figures, Namık Kemal’s writings became the main attraction because they addressed more fundamental issues. Niyazi Berkes, in his classic work The Development of Secularism in Turkey, has described Namık Kemal’s eight Letters on the Constitutional System published in Hürriyet during September-November 1868 as ‘the first attempt to explain to Turkish readers the theory underlying liberalism and constitutionalism’.

Meanwhile, the Sublime Porte had come up with an interesting offer: it would itself take two thousand copies of each issue from London, provided that the paper toned down its criticism. Ziya immediately rushed out an article with the headline ‘Yaşasın Sultan Aziz, Bravo Bâb-I Âli!’ (‘Long live Sultan Aziz, Bravo Sublime Porte!’ Perhaps this made the Porte suspicious of being taken seriously, for no money ever arrived. However, Ziya eventually accepted a subsidy from the Khedive of Egypt, Ismail, who wished the paper to use the opening of the Suez Canal to emphasise his independence from Istanbul. Namık Kemal disagreed with this, and gave up his involvement with Hürriyet on September 6 1869, leaving Ziya to carry on as sole editor. The paper became increasingly polemical, finally going too far when Ziya published an article by Suavi suggested that the simplest way of removing the Grand Vezir Âli Pasa would be to assassinate him. When the Porte protested to the British government, which then started a law suit, both Ziya and Hürriyet fled to Geneva. The paper did not last long. However, the name lingered in folk memory, and Sedat Semavi did well to call the now very successful newspaper which he started in May 1951 Hürriyet.

Namık Kemal stayed on at Fitzroy Square for several months. With the help of his friend Fanton, he was supervising the printing of a special edition of the Koran for Mustafa Fazıl Pasa. In July 1870, on the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, he moved to Belgium. Here he received, in what must have been a concerted action, letters urging him to return to Istanbul and assuring him of his safety. They came from the chief of police Hüseyin Hüsnü Paşa, the private secretary to the Grand Vezir Âli Pasa, and Halil Şerif Paşa, ambassador in Vienna and son-in-law of Mustafa Fazıl. Halil Serif added an invitation to stay with him in Vienna on the way. It took another three months to persuade him, but in October Namık Kemal was in Vienna. On November 22, he finally arrived back in Istanbul. His family were at Sirkeci station to greet him.

His life soon resumed its extraordinary mixture of activities. While turning increasingly to writing plays, he also resumed his journalism. In July 1872 he became editor of the newspaper İbret, only to find himself appointed governor of Gallipoli three months later. Dismissed from his governorship in March 1873, he arrived back in Istanbul just in time for the first performance of his defining patriotic play Vatan Yahut Silistre (The Fatherland or Silistria). The enthusiastic applause brought the house down, but also brought down on his head the wrath of the authorities, who imprisoned him in Cyprus in the prison which is still preserved as a museum dedicated to him. Released, and then again exiled, he made a speciality of the Greek islands. First exiled to and then governor of Mytilene, he then moved to Rhodes as governor. It was there that he gave his blessing to the marriage of my great-grandparents: Menemenlizâde Rifat Bey, a civil servant, had been sent to keep an eye on him, but had instead fallen under Namık Kemal’s spell and in love with his daughter Feride. Increasingly unwell, he turned in his last period of life to writing a history of the Ottoman Empire. He died in the governor’s mansion on Chios of a lung disease on December 2 1888.

Osman Streater

|

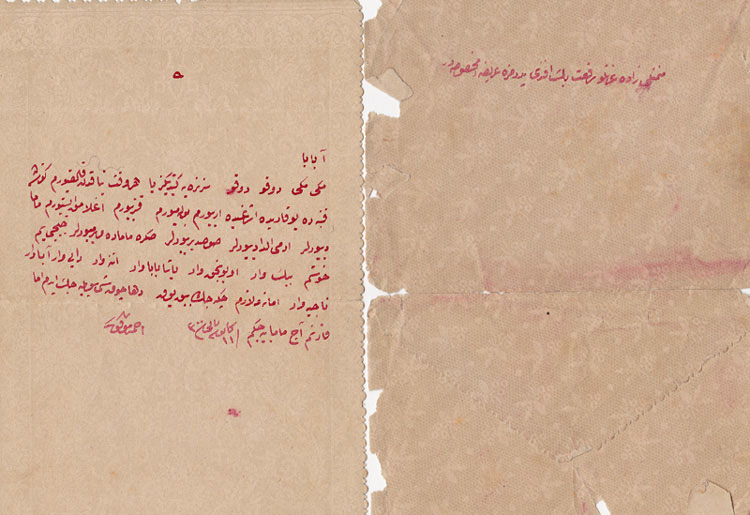

letter that Namık Kemal wrote “on behalf” of my newly born Grandfather Muvaffak Menemencioğlu to his father - the date is January 1885 (1300). Namık Kemal died 3 years later in 1888, at the age of just 48. On the other hand, while in Paris before coming to London 1867-70, he had acquired a taste for cognac, of which he drank nearly a bottle a day.

Transcription: A Baba

Miki miki doku doku. Siz nereye gittiniz ya her vakit yatakdan kalkıyorum gözümle ?kanbiyede yukarıda aşağıda arıyorum bulamıyorum. Kızıyorum ağlamak istiyorum.

Mama diyorlar adam aldatıyorlar susturmuyorlar. Sonra mama da vermiyorlar. Ciciyim hoşum bebek var oyuncak var Paşa Baba var Anne var Dayı var Abla var Naciye var ama neme lazım çekecek büyük yok. Daha çok şey söyleyecek idim ama karnım aç mama yiyeceğim

11 Kanuni-sâni sene 1300

Ahmed Muvaffak

Rough translation: Dear Father

A rhyme... Where do you keep going, each time I open my eyes you seem to wander off. I get angry, I want to cry. They say food but don’t deliver, they can’t silence me. I am sweet, I am cute, I have got a father who is a Pasha, I have got with me my mother, uncle, my sister and Naciye, but I want some good food and an adult to feed it to me. I had more to say, but I am hungry, need to eat...

23 January 1885

Ahmed Muvaffak

An earlier letter from Namık Kemal

Transcription: A Baba

Miki miki doku doku. Siz nereye gittiniz ya her vakit yatakdan kalkıyorum gözümle ?kanbiyede yukarıda aşağıda arıyorum bulamıyorum. Kızıyorum ağlamak istiyorum.

Mama diyorlar adam aldatıyorlar susturmuyorlar. Sonra mama da vermiyorlar. Ciciyim hoşum bebek var oyuncak var Paşa Baba var Anne var Dayı var Abla var Naciye var ama neme lazım çekecek büyük yok. Daha çok şey söyleyecek idim ama karnım aç mama yiyeceğim

11 Kanuni-sâni sene 1300

Ahmed Muvaffak

Rough translation: Dear Father

A rhyme... Where do you keep going, each time I open my eyes you seem to wander off. I get angry, I want to cry. They say food but don’t deliver, they can’t silence me. I am sweet, I am cute, I have got a father who is a Pasha, I have got with me my mother, uncle, my sister and Naciye, but I want some good food and an adult to feed it to me. I had more to say, but I am hungry, need to eat...

23 January 1885

Ahmed Muvaffak

An earlier letter from Namık Kemal

|

My late mother inherited this letter, and on the anniversary of Namık Kemal’s arrival in London, 1967, she started to try to get a Blue Plaque erected on 15 Fitzroy Square. But I remember her being very angry that her request was rejected. When I inherited the letter, I took the matter up with English Heritage by phoning them. Within seconds, they had found the file. They said that my mother had fully proved Namık Kemal’s importance to them, so he did indeed deserve to become only the second Turk to have a Blue Plaque. The trouble was, however, that they required several different items of evidence proving an address. And that was the problem. I have tried family and friends, I have tried historians and journalists in Turkey. But Namık Kemal (other than the “Baba” letter) always scribbled letters quickly and a little carelessly. And he never wrote his address at the top, or anywhere. This one letter is still the only piece of evidence that he lived there during his time in London - probably moving there in 1868 until he left in 1870. But it’s no good. We need more pieces of evidence, and we can’t get them anywhere unfortunately.

Transcription: Reşadım Evladım,

Daha henüz yerleşebildim. Mektubuna cevap vermediğimi affet. İşte yeni adresim:

15, Charlotte Street, W.

Fitzroy Square

Kevkebe’yi Sarki’yi iade ettim, kim yazdıysa bir daha eline sıçayım. Köpek ürümesini bilmez, koyunu kurt çağırıp duruyor. Biz eşeğiz a, İstanbul bizden şeddeli, bizde uzun kulaklı.

Biraz sabret – sana bir Shakespeare göndereyim ki görenler hayran olsun. Apartmanım gayet nefis: bir âlâ salonu, üç nefis yatak odası, bir mutfağı var. Ayda yüz on Frank. Lakin döşemesi bizim sahibenin. Görsen hayran olursun. Kibar olduk gitti. Bizim ‘Duruva’ dersi hayliden hayli ilerledi. Yani ‘Economie’ye’ yarı ettik evladım.

Biraderin

Kemal

Rough translation: My dear son Reşad

I have only just settled in. Forgive me not replying earlier, here is my new address:

15, Charlotte Street, W.

Fitzroy Square

I have returned the song, whoever composed that may I crap on his hands. The dog doesn't know how to reproduce, he cries wolf to the sheep. We are like donkeys, Istanbul is cleverer and long eared than we are.

Be patient - let me send you some Shakespeare so those who read it are enraptured. My flat is very luxurious, a nice living room, three lovely bedrooms and a kitchen. It is 100 Franks a month. The furniture belongs to the owner. If you saw it you would be amazed. We have become burgeoisie here. Our ‘Duruva’ lessons have progressed well. So were are half-way to ‘Economy’.

Your friend

Kemal

Transcription: Reşadım Evladım,

Daha henüz yerleşebildim. Mektubuna cevap vermediğimi affet. İşte yeni adresim:

15, Charlotte Street, W.

Fitzroy Square

Kevkebe’yi Sarki’yi iade ettim, kim yazdıysa bir daha eline sıçayım. Köpek ürümesini bilmez, koyunu kurt çağırıp duruyor. Biz eşeğiz a, İstanbul bizden şeddeli, bizde uzun kulaklı.

Biraz sabret – sana bir Shakespeare göndereyim ki görenler hayran olsun. Apartmanım gayet nefis: bir âlâ salonu, üç nefis yatak odası, bir mutfağı var. Ayda yüz on Frank. Lakin döşemesi bizim sahibenin. Görsen hayran olursun. Kibar olduk gitti. Bizim ‘Duruva’ dersi hayliden hayli ilerledi. Yani ‘Economie’ye’ yarı ettik evladım.

Biraderin

Kemal

Rough translation: My dear son Reşad

I have only just settled in. Forgive me not replying earlier, here is my new address:

15, Charlotte Street, W.

Fitzroy Square

I have returned the song, whoever composed that may I crap on his hands. The dog doesn't know how to reproduce, he cries wolf to the sheep. We are like donkeys, Istanbul is cleverer and long eared than we are.

Be patient - let me send you some Shakespeare so those who read it are enraptured. My flat is very luxurious, a nice living room, three lovely bedrooms and a kitchen. It is 100 Franks a month. The furniture belongs to the owner. If you saw it you would be amazed. We have become burgeoisie here. Our ‘Duruva’ lessons have progressed well. So were are half-way to ‘Economy’.

Your friend

Kemal