Fred Charnaud & Madeline Chasseaud Family Story

Michaeal Charnaud, 2012

Chapter 1

History gives a nation a bearing on what it is, and how its people are affected by what has happened in the past. The kings and queens, wars with victories and defeats all mould a nation’s culture into how it views itself in the present. In the same way a family history shows how it has had to survive and come to terms with all the great social and cultural of the age. I hope this story will help give each member of our family a foundation, and try in a small way to explain how we came to be what we are today, and also be a help for generations to come to see the sort of energy and dynamism, the loves and hates, errors and mistakes, the victories and defeats that should make a fascinating read with hopefully some lessons to be learned.

Legend has it that the Charnaud family originated from the city of Carcassonne in the South West of France. I have no precise idea as to whether this is in fact true, but the likelihood is that it is so. The family carries a coat of arms handed down from antiquity which consists of a shield of four quarters with one in the centre. The opposite diagonal quarters consist of a star on the one side, and a fleur de lys on the other. In the centre is a castle turret and the family motto is “Sans Peur” (without fear).

The first direct ancestor that we know was one Jean Samuel Charnaud and was a French Huguenot refugee from Pont de Veyle Bresse. He moved to Vevey in Switzerland following an edict in 1685 expelling Huguenots from France. The family continued living in Switzerland until his grandson Jean came to England and was made a British Subject by an Act of Parliament in 1762. He later moved to Smyrna where he became a factor and he died in 1773 out there. The family tended to live in the Levant and traded and lived between Smyrna and Alexandria. His second son John in due course fathered my great grandfather Frederick. He was a shrewd businessman and was one of the original backers of de Lesseps in the construction of the Suez Canal which earned him a fortune and he was able to send my grandfather Alfred to be educated at Harrow. It was said of Alfred the only thing that he ever learnt there were polished manners, a charming manner, and an insatiable appetite for pretty girls. Shortly after leaving Harrow his father died leaving him a fortune worth in those days £250,000 and probably worth 50 times that amount today. He was a wonderful raconteur and told us once how he had been badly bitten by a dog and so decided with some friends to journey to Paris to be treated by Pasteur against rabies.

On the train to Dover the compartment was very full and one of his companions let it be known the reason for his journey; at this point Alfred started growling and snarling like a dog and within minutes all the other passengers had moved off and he and his chums had the compartment to themselves! He spent a number of years in Paris, which he greatly enjoyed and it was there that he got an interest in geology and above all he became interested in the extraction of chrome. He moved to Smyrna in Turkey and began prospecting. He had married my grandmother Elise Icard [Elisabeth Marie Icard 1862-1957, daughter of André Icard & Maria Zipcy], a pretty olive complexioned girl and she gave him two daughters, Lucy and Lilian and my father Frederick Christian Joseph.

Grandmother Elise Icard. |

Alfred Charnaud aged 50 years (born 1862). |

Alfred Charnaud aged 75 years. |

Alfred first developed in Turkey a corundum or emery mine which was moderately profitable before continuing his search for chrome. There were ample signs that the mineral was there in quantity, but in those days he lacked the diamond exploration drills and he kept on sinking shafts one after another exhausting his financial resources. The tragedy was he kept searching on the south side of the mountain range, and years later there is a productive mine which was developed on the northern slopes.

I was only six years old when I met him on a visit to Turkey in 1937. He was a jolly man in his late 70’s who lived in the next village with his mistress 20 miles away. Every Sunday however he would come to have lunch with his wife who is said was a far better cook. I was as a small child impressed with his strength. He was the only person I have ever seen who could put a walnut between his two fingers and crack it!

As a result of the wastage of money, first the grand Charnaud House in the most fashionable part of Smyrna had to go and instead the family moved to cheaper accomodation over the bay in what was then called Cordelio (named after King Richard Lionheart or Coeur de Lyons). The district is now called Karşıyaka by the Turks.

Father was born in 1890 in Smyrna which was at time under concessions to the leading European powers as a trading port following the Crimean War. Under this system each power such as England or France would be responsible for their own nationals under their own legal system. Thus there would be an English magistrate, Vicar, doctor, consul etc to maintain law and order for its own subjects. The rest of the population of the city was much as it had been for 2,500 years i.e. mainly Greek who controlled all the commerce and the agriculture of the immediate hinterland. In classical times the district was known as Ionia and it was reputed to have had the finest climate in the ancient world. The Turkish presence was confined to the military and government administration. With a large cosmopolitan population, it was easy for children to learn languages. In our household the normal language was French as that was what Elise spoke, as she had never been to England having been brought up in Paris, but Alfred would also converse in English with friends particularly with his friend the English vicar. The maids were Greek, and other children nearby would be speaking Italian or German.

There was practically no money in the household apart from the barest essentials. Food was cheap with the abundance of vegetables such as aubergines, tomatoes, beans etc. which were made into tasty dishes with the barest minimum of meat. It was quite out of the question for father to receive any formal education. Friends of the family would help out, and my father was helped in his education by the English Vicar who gave him his basic lessons in English, and encouraged him to read widely. Elise was a most devout Catholic and although she had married a Protestant all the children were baptized Catholic, as in due course in deference to her, we of our generation also were. Every day she would rise and go to early Mass and invariably come back and drink a bottle of beer. It may have been this regime that enabled to live to the ripe old age of 98.

When father was young she had an extraordinary experience. The house at Cordelio became infested with rats and she had tried everything to get rid of them without success. Someone eventually told her that there was a Turkish Hodja from a mosque in the next village who was an expert in charming them. She was at first very reluctant to have to go and see a Muslim Cleric, as she felt it was a betrayal of her faith, but eventually she swallowed her pride and asked for his help. He came next day and told her to light an oil lamp and walk up to the local mosque and then walk round it three times and he would then join her. She did this and he then took the lamp back to the house here he chanted and chanted and from there he went over the road to the sea. As he did this the rats rushed out of their holes and hiding places and followed him over the road and over the edge of the sea wall where they tumbled into the sea and drowned. She was never ever troubled again! It is an amazing story and the whole family used to repeatedly retell the story and marvel how it was done, and how it compared with the ancient story of the pied piper.

As he grew up into his late teens it was a great worry to the family as to what he could do. Opportunities in the British Concession in Smyrna were meagre, but then there was a fortunate stroke of luck. Alfred had been very friendly with the Whittall family, in Smyrna. They were phenomenally wealthy traders with branches of the family scattered throughout the Levant and also the Far East. One of the branch had in the mid nineteenth century gone to Ceylon and started a trading house which to this day bears their name. Fred Whittall a relation had also gone to work in Colombo but did not like it, and instead went tea planting upcountry as he was keen on growing things and preferred the better climate.

He returned back to Turkey in 1907 on leave and went to see his old friend Alfred who told him of the problem facing his son.

“He is a good lad, very studious and hard working, an excellent shot and I am sure you could find something for him out there to get his teeth into”.

“Well as it happens” said Fred Whittall”, I have a problem which may well work out right to our mutual advantage. I will train him in tea planting, and help him find a job on the one condition that when I retire in 10 years time, he will come and manage the new Estate of Luckyland that I am opening up. If he is agreeable and gives me that solemn undertaking then I will help him to the best of my ability”.

Father jumped at the opportunity. At last there was an opening to a wider world and he had an entree which whatever happened would lead him to new experiences and a technical training, and the rest would be luck and his unstoppable energy and ambition. He also told me that as a boy he was acutely self conscious of the tragedy of his father losing his fortune, and the penny pinching which followed, all the harder when the family originally had wealth and position. He was determined to rectify and restore the family fortunes. So it was on a bitterly cold day in the first week of February 1908 still only 17 years of age, that he boarded a ship at Smyrna, bound for Alexandria, from where he could connect with a Bibby Line boat for Ceylon.

As he left home the family bade him farewell, and Alfred gave him £5 for his travelling expenses and starting him off. He tucked himself well into his great coat against the biting wind, and Elise kissed him and also asked to post a letter to a friend which he promptly put in his great coat pocket and forgot. Once the ship was on its way, he never looked at his coat again until 1914 when he came home that winter to join up. He then found the old letter from his Mother which he opened, to see that she had written to say how glad she was that he was at last going away, as he was getting on her nerves and also was getting too fresh with the young Greek maid, and if he had not been leaving, no doubt she would soon be pregnant!

LIFE IN CEYLON

Father eventually arrived in Colombo in March 1908 when he was almost 18 years old. The contrast of Colombo with its heat, the glaring sun, humidity and thriving bustle was in complete contrast to sleepy Smyrna. After the debacle and the wiping out in the 1880’s of coffee due to a fungal blight, there was a tremendous upsurge in replacing the blighted area with tea. The other crops such as coconut mainly grown for its oil, and the new emerging rubber plantations, had given the island now with 2 million inhabitants an unbelievable prosperity. Colombo with it position astride the main shipping routes to Australasia and the Far East, was primarily a refuelling port and was reckoned to be the second busiest port in the world after London.

The climate was in complete contrast to the stark dry summers of the Mediterranean which also had winters, and a floral spring that carpeted the hillsides with flowers. Instead here were palms, brilliant yellow cassias, scarlet flamboyants, and a whole host of other flowering trees. The walls and sidewalks were clothed in bougainvilleas of every colour and ginger lilies of every description thrived in the hot, sticky clammy heat. Almost every day in the ensuing few months, there would be sharp thunderstorms, drenching the land with rain, followed in turn by brilliant sunshine, so that the hothouse environment completely dominated ones life out there.

After paying his respects at Whittalls Agency Head Office in the Fort District of Colombo, he took the train upcountry through the steamy low country of palms and rubber trees, into the great open vistas of the tea country. The single track railway itself was a marvel of engineering hacking its way through precipitous granite mountains, with a sheer determination of tunnels, terraces, bridges all blasted out by hand with gunpowder and dynamite. Eventually some 8 hours after leaving Colombo the main line train stopped at Nanoya station, from where he changed onto a minor narrow gauge which took him to the hill station of Nuwara Eliya 6,500 ft above sea level and cool like a European country. After spending a night at the Grand Hotel, in the cool he took the little train down towards Ragalla which was the end of the line, where he was met by Fred Whittall on horseback. They welcomed each other, and walked on for about 1/2 mile towards Ragalla Bungalow where they were due to have lunch. As they rounded a corner they were met by a horse and trap and two very smartly dressed young men in velvet coats and cravats looking very raffish as they drove swiftly by.

The smartness of the scene took Father completely by surprise. After a day and a half’s travel from the hot city of Colombo, to the outback of the hill country, the last thing he expected to see were such elegantly dressed men. He turned to Fred Whittall and said, “They seem very smartly dressed for the outback upcountry. Who are they?”.

Fred pulled up his horse and turned to him sternly, “They are your next door neighbours, the brothers Charlie and Hubert Patterson, on Allagolla. Let me make one thing quite plain, if I ever catch you having anything whatsoever to do with them, it will mean the sack instantly. They are the most wild and disreputable rascals in the district, constantly drunk and constantly causing a commotion. The Superintendant of Police and Mayor has banned them from ever setting foot in Nuwara Eliya any more, and as I said a similar ban applies to you from having any dealings with them”.

And so they proceeded on to Ragalla for lunch, and over the years the Pattersons became very close friends as will become clearer later. After lunch they rode through the beautiful district of Udapussellawa through to Gampaha Estate where Fred was planting, with his new Estate of Luckyland adjoining. Udapussellawa is one of the finest tea growing areas of Ceylon and is situated on the North Eastern side of the main range at an elevation of about 4,000ft to 5,000 ft for the most part giving it a cool climate rarely exceeding 75 F. (24 c.) in the shade at mid-day and dropping to rarely less than 50F (10 c.) at night. It has stunningly breathtaking views over the wild low country jungle below the cascading hills which drop away sharply from the main tea areas. At dawn one looks far to the east, to see the grandest and most colourful sunrises with range upon range of low hills, their valleys filled with mist so that they emerge like islands in a sea of white foam. The worst time of the year were the winter months of November to January when all the clouds of the North East Monsoon would accumulate like lumps of cotton wool, and get denser and denser until it was so thick that one was hard pressed to see the edge of the little road one stood on. And then the rain would come, inches and inches at a time, in an absolute deluge to give an average rainfall of 125 - 150 inches for a year.

They arrived that evening at Gampaha bungalow which was at about 5,000 ft high facing the beautiful view, with the mountain peak of the Buffaloes Hump sweeping up to the right about 700 ft higher. They walked down the stately drive lined with gigantic Eucalpytus and fir trees and were met by his very kind and gentle wife Althea who was to be a great comfort to the young “creeper” in the days and months to come. Next day father moved 2,000 ft down the hill to the Assistants bungalow which was adjacent to the factory and the other staffs bungalows.

Father used to describe his two years at Gampaha under Fred Whittall as the hardest and toughest days in his whole life. Fred was a short dark haired man, who had survived the harsh trauma of the coffee smash, by sheer dominant willpower, determination, and an incredible meanness and thrift. He was one of the old pioneers that gave Ceylon its great industry, and it is a tribute to unpleasant and hard people that at the end of their lives they left a legacy of an industry that even today with all the politics that have been played with it, still survives. It must also be remembered that in those days tea took some 7 years to start coming into production, and there was all the continuing expenditure with a revenue that was slow to materialise and even then the returns and yields were very modest of only about 300 lbs of made tea produced per acre, a tenth of the amount that can be achieved today with fertilizers and high yielding clones.

Fred took him round the estate and showed him his duties. Father was given an allowance of one pencil a month to do his check-rolls and keep his books. God help anyone who would dare to exceed this allowance. He spent his time running from one hill at 5,000 ft, down 2,000ft to the valley and up the other side three or four times a day, weighing pluckers and seeing to all the estate works, the strain of which he swore had a lasting effect on weakening and giving him an enlarged heart. He always used to tell me, that in subsequent years when he was in the Army no Sergeant Major or any other officer for that matter, was as hard, rude and persistently ruthless as Fred Whittall was on Gampaha.

There was no mercy for anyone from the lashing and vulgarity of his tongue. One late afternoon in the factory he was tasting teas by the open window, when the Sinhalese Baas (Building Contractor) approached him about some matter. He took a drink of tea rolled it round his mouth and spat in his face. “That is to teach you you damn rascal, that the workmanship on the labour quarters you built was appalling.” Shortly after he repeated the performance on one of the Tamil minor bookeepers.

Father used to be absolutely terrified of him when he was in one of his moods. At dawn he would come up to the rear of the big bungalow and look into the kitchen to see Althea. Some days she would say it was quite safe, as he was in a reasonable humour, but at other times she would gesture him off as he would be in a foul rage.

One day however Father said he came to find her, but she was no where to be seen, so he gingerly walked round the house and there on the front lawn was Fred with the head Kangany, the Tamil who was not only in charge of all the labour, but was also the chief who had recruited them from his villages in South India. Fred was still dressed in his pyjamas and had got the Kangany’s head wedged between his legs and was pummelling his sides for all he was worth. “You Goddam Rascal” he kept shouting, and then suddenly his pyjama trousers ripped and Father was faced with his big hairy arse sticking out as he crept away, never ever discovering what sort of error or crime the poor man had committed!

On other occasions Fred could be quite charming. He was a very good shot and so often on a Sunday they would walk down to the Welmada plain which was mostly patana or grassland, with their guns to shoot partridge or wild pigeon. After a days hard slog there was the long climb back of 2,500 ft. If they had a good day and he was happy, Father would be allowed to hold onto one of the horses stirrups to help him up hill. Never once did he lend him a horse, or even take him on his, which as they were both small men the horse could easily have borne.

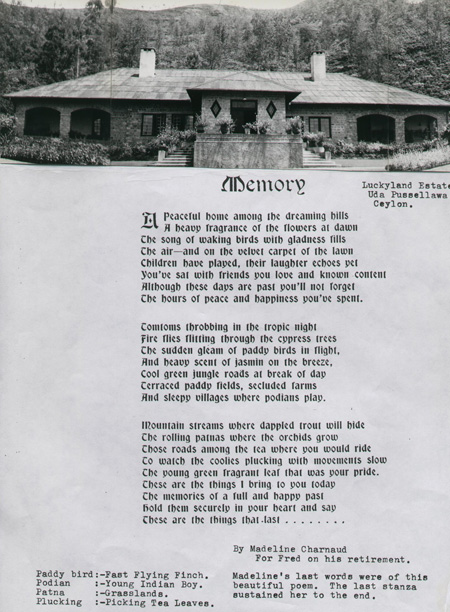

Meanwhile the new Luckland Estate was being developed as a private personal sideline. The aspect of the Estate was beautiful on the southern slopes of the Buffaloes Hump overlooking the whole Welimada plain below and in the far distant view, to the Horton Plains (7,000ft) and its peak of Totapala 8,000ft. Straight ahead on the horizon was the long Haputale range flat on top at about 6,000ft leading in the East lonely like the last sentinel, the Uva Peak of Namunakula. The upper reaches had all been jungle which had been cleared and planted first whilst the lower areas were still being planted. The tea was only just coming into production and the building of the new giant Luckland bungalow with its 120 ft corridor was only just commencing. There was no factory yet, this problem had yet to be resolved and the little leaf that was being harvested was transported to Gampaha next door.

Shortly after Father arrived in 1908 the world was paid a visit by Halley’s Comet which was a spectacular sight with it tail spreading almost from horizon to horizon. In the clear dark upcountry atmosphere the view was breath-taking, but the coolies all without exception took it as a bad omen and were frightened.

About 9 months after he had come out during the misty north east monsoon they both went one afternoon in the gum plantation with a couple of dogs to shoot hares which were plentiful amongst the trees and the high patanas. Suddenly there was a roar and the most terrifying thing of Ceylon was on them. Somehow they had upset a swarm of the giant wild Bambara bees each of which is three times the size of an ordinary honey bee, and notoriously bad tempered in the cold misty season. They all flew on to Fred’s head and would have killed him had not Father luckily his cigarette lighter handy and was quickly able to get a fire going with the resinous aromatic gum twigs. Soon he had ample smoke to quieten them down and give a place of refuge. But most years when I planted there was always talk of some coolie or villager being attacked. I used to be very wary myself and when one heard the sudden roar of a swarm would take cover and protect my hair above all, lest one get entangled and creates a scent which attracts the rest in their thousands with the most painful consequences!

For relaxation there was the local Dickson’s Corner Club, but apart from the Annual Tennis Meets it was difficult to get to with the lack of transport. However after a year he purchased a second hand Royal Enfield Motor Cycle. On his first trip on the 30 miles tortuous road to Nuwara Eliya, he came round a corner and almost had an accident with a gentleman in a pony and trap.

“Who the hell are you?”, the man enquired.

“Fred Charnaud from Gampaha Estate”

“Well haven’t you heard of keeping left?” he spluttered.

“No never. What for?”

“Well as there is now an increasing amount of road traffic, it has been made a rule that if everyone keeps to the left, there is less likelihood of an accident being caused.”

“Thanks I will remember that for the future.”

Father said it was the first time he had ever been aware of keeping to the left. He had been brought up in the era of horses, and it was easy to avoid one when one was trotting slowly and both in Turkey and his life in Ceylon up until then, there was no cause to be involved with traffic in any way.

Whilst he was on Gampaha they had a visit from a young French Nobleman about which more will be said later in this story. Suffice to say that he was on a tour of India and the Far East and had called in to Ceylon, and given an introduction to Fred Whittall to take him out shooting. He and father got friendly as they stalked Partridge and snipe in the Welimada plains and valleys, and he got the idea of starting up his own tea estate. But more of this later.

Soon it was almost two years father had been at Gampaha, and he was now in a position to move on. He bade his goodbyes to some rumbustious friends from the nearby estates who would often join him for a drink in the evening at his house. One was a wild chap who always carried a revolver in a holster, and when he had too much to drink would draw his gun and shoot at the hornets that would congregate on the ceiling ventilator. He had obtained an assistants appointment on a small Estate in Dolosbage, near Adams Peak, and one of the wettest areas of Ceylon.

Chapter 2: THE EVE & START OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR

Tamaravelly Estate was owned by a very old planter who was almost blind. The property was in a most deplorably run down state, a great contrast after the hard ruthless efficiency of Gampaha and Fred Whittall. The rainfall was terrific at about 330 inches for the year that he was there. Most of it fell during the South West monsoon from May till September when being situated on the hills near Adams Peak it caught the full force of the tropical depressions and storms. To put this figure in perspective, it is about 12 times the annual rainfall for London! Most of the top soil had long been washed away, and the bushes were perched up on their roots amongst ground that was a sea of weeds. Money was desperately short, on account of bad management, so nothing could ever be done properly. Still it was a relief and a welcome change from Fred’s martinet ways.

The old planter would stumble along and once a day go down to the factory in the late afternoon to hear what was going on. If the pluckers were being weighed at the end of the day, he would go amongst them and could recognise each by either their voice or by squeezing their tits. “Ah Meenatchy” he would say as he felt her, “How is your little boy coming on? Has he got over his flu?” The Tamils in their respectful way all accepted this with giggles and good humour, as it had just become a daily part of the scene!

After a year of this bumbling he was lucky to get his first managerial appointment at Mottingham Estate in Maskelya, now a Division of Brunswick Estate where the rainfall was less than half and was at a nice elevation of about 4,500 ft in the centre of one of the great tea growing areas. There were a number of good planters clubs nearby with an active social life, so that he could enjoy life and play tennis, a sport that he could excel in. It was a welcome break and a chance to really partake in all the fun of upcountry life after three years of hard slog.

One of his first jobs at Mottingham was to get the accounting system organised and he worked hard at this, correlating all the estate books, until finally he worked late into the night producing a fair copy to be posted down to Whittall’s next day. He finished the copy and placed it in the drawer of his desk, only to find to his horror next morning that in the night a mouse had got in and made a nest, so he had to start all over again! The Estate looked up to the pointed sacred mountain of Adam’s Peak (7,900 ft) where at the summit is a huge footprint on the rock that the Buddhist’s say was made by Lord Buddha. There is a lit pathway and steep steps up to the summit, and the thing to do was to climb up the peak at night and watch the dawn rise. If it had been raining and cleared, the surrounding valleys would be clothed in mist and one would see the huge triangular shadow of the peak silhouetted on the snow white mist below.

|

The next three years were idyllic, and he could look back with pride on his accomplishments. He had come out to Ceylon just before his 18th birthday, and in spite of a lack of any formal education, had made his way well, under a peculiarly harsh taskmaster and only three years later had got his first charge when only 21 years old.

He was now fluent in English as his first language instead of French which had always been spoken at home, and was starting to read widely to build up his general knowledge. He was planting in one of the most pleasant districts in the country, with a tremendous social life, and he had at such a young age achieved his first managerial charge of a small estate.

All this was soon to come to an abrupt end in August 1914 with the outbreak of the First World War. To start with the general feeling was one of excitement. There had not been a major war in Europe since Napoleonic times, a hundred years earlier. Most wanted to see a bit of action before it was too late, and few thought that it would last more than six months at the very most. Everyone was joining up to do their duty and the general atmosphere was more like trying not to miss a low country shoot, than giving serious consideration to the vast array of artillery and machine guns that had been built by firms such as Krupps and Vickers, and the destructive killing power that would inevitably ensue. The thought of a callous insatiable mincing machine that would simply devour the youth of Europe and the colonies in their millions over the next four years, was completely beyond the average mans’ comprehension. Father was just one like many in October, 1914 when he decided that he must volunteer with all the other young men of his age.

He wrote to Whittalls, his managing Agents in Colombo to inform them, and received back a reply which was very negative and upsetting. They said that under no circumstances would they allow him to go, as they had already made plans as to who they would require to continue the management of the estates, and he was on that list. Should he decide to depart, contrary to their advice, the consequence would be that he could not necessarily expect to have a job waiting on return, as having already gone against the wishes of the Agency, he could consider himself sacked. Nevertheless he decided to go, but had no money for the trip. He held an auction of his few possessions in Maskeliya Club and all the old planters bid ridiculous prices to help him on his way. One old planter R.K. Clarke even paid £5 for a pair of rabbits (£500 today) and so it was that he eventually raised enough to get a steerage passage home. This meant that there was no cabin berth and one just slept on deck or anywhere one could find room. But it did not worry him. Everyone was young, and there was a tremendous excitement and abandonment amongst all the crowd that was packed on board.

Eventually on a bitterly cold frosty evening the boat disembarked the steerage passengers at Plymouth where they were led to a freezing warehouse and told to bed down until the morning. Shortly after they were about to settle in, some trucks drew up and everyone was told to get in, and he ended up with a friend in one of the best hotels for the night between nice clean bedclothes that he had not been used to since he had got on the ship when he left Ceylon. On enquiring how it was that their circumstances had changed so suddenly, he was told that one of the party knew a civic leader in Plymouth and had telephoned him about their plight. The gentleman in question was a Masonic Grandmaster and had contacted all the hotels etc. and his fellow freemasons to open their doors free of charge for the plucky band of volunteers, which is how he came to have his room.

The following day he journeyed to London to enlist in the Artists Rifles. This was a regiment originally set up to cater for the artists and intellectuals of Chelsea, but increasingly it had come to include colonials and other expatriates with an overseas background. At the same time he went to the City to visit the head office of Whittalls, to show them the letter that had been written by their Colombo Directors threatening him with the loss of his job for have joined up.

“What do you think of this letter?”, he asked worryingly, “It is a terrible and unpatriotic thing to have hanging over ones head like a sword of Damocles, when all I am doing is my natural duty along with so many of my friends. I wonder what John Bull would make of it in the press if I were to pass it on. They would have a field day with a story like this”.

One of the directors leaned over and said, “I don’t think there is any need for that. Of course we will give you a letter confirming your appointment, and in the meantime here is a cheque for £400 to cover your personal expenses for the time you are here as we know coming steerage you must be short, and in exchange we will keep the letter.”

This was an amazing eye-opener to the conditions in London, which he was visiting for the first time in his life. Horatio Bottomley with his magazine John Bull was waging a witch hunt on anyone who was not pulling their weight and being unpatriotic. His paper castigated and pilloried anyone or any organisation who in his eyes were German sympathisers, in the most hysterical way. There were witch-hunts started that could ruin anyone and his defamations were avidly approved by the great mass of the public. Father said that coming suddenly from abroad, he had never really understood the fearful reputation, the magazine had in the eyes of the public, and the suddenness of Whittalls response, took him completely unawares. Anyway he accepted the cheque with alacrity, as after all in a war situation one tends to live just for the day, and with this vast bank balance worth so much more than today, he could really enjoy himself in London with no financial constraints for the short period before his training was due to start.

Another thing he did on his arrival in London, was to go to a mansion in Ladbrooke Grove, which he had heard was a meeting place for people from Turkey, to see if there were any childhood friends that may be there. It was at that house that he came across by chance the two young daughters of Doctor Henry Chasseaud who had been practising in Smyrna, and who now was also a surgeon at the British Seaman’s Hospital in Greenwich. Madeleine and Helen had been in England at school for the previous 9 years, but there was a bond there, although in Smyrna they had moved in different circles, the Chasseauds being very wealthy, whilst his family had fallen on hard times.

Chapter 3: THE CHASSEAUDS

The Chasseaud Family were like the Charnaud’s also Huguenots from France probably from the St Nazaire region. The family crest is a rampant stag on a mountain crest with three stars above. Originally the family were chamois hunters from the Alps, but after the massacre of St Bartholemew of the Huguenots at St Nazaire, the family moved to Jersey. My great grandfather wanted to study medicine, and this he did under Dr Simpson, the pioneer of anaesthetics at Edinburgh. It was shortly after he graduated, at Simpson’s instigation that he went out to the Crimea War to help with the terrible outbreaks of cholera in particular, but also to tend to the wounded under the appalling conditions out there. It was whilst in the Crimea, that he developed a liking for the relaxed Mediterranean way of life, with its shorter winters and so got a job after the war in the new British concession at Smyrna. There he was the doctor for the British community and the British Seaman’s hospital.

He was a man who had an intense respect and a feeling for the occult, and in fact wrote a book on the subject based largely on the experiences he had with his second wife (no relation of ours), who was an acknowledged psychic. An example that he used to often relate was that on one occasion she awoke in the middle of the night terribly agitated, to say that she had dreamt or heard in a trance, of a poor Mother screaming for the doctor from a very poor street in the city. He summoned his carriage and as they went up the street slowly, a woman rushed out crying and weeping, “Thank God it is you Doctor, my son is in agony and dying”. He was able to take the boy who had acute appendicitis, operate on him, and save his life! Without her intervention he would have been completely unaware of the crisis.

In turn his son Henry, my grandfather also went to Edinburgh to study medicine. After graduation, amongst other things he was a medical officer to the men working on the Forth Bridge when in those early days of civil engineering there were the most appalling number of casualties. He eventually took over his Father’s practice in Smyrna, and married Helen de Kramer an Austrian from a Merchant Banking Family in Salzburg, who’s father in turn had married the family’s gardener’s, daughter. He was an Englishman called Perkins and it is probable that both my mother’s and my intense love of gardening has its roots derived from this love match!

They had three children, Madeline who was to become my Mother and was born on the 13th February 1897, Helen a year later, and a third child Elizabeth who died at about eighteen months old. They were brought up in a very multilingual family environment speaking English and German equally at home as they also had a German nanny. At the same time however most of their childhood friends spoke French, whilst in the home the maids spoke Greek. In this way the two sisters were able to communicate easily in four languages. Because her friends were all French and she found the German environment at home oppressive, after a great deal of pleading the sisters were allowed to go to school at the French Convent where they remained until 1907 when they were brought to England.

One evening when she was about six years old the doctor summoned the girls to come into the drawing room well dressed before they went to bed.

“I want you to meet a very famous Englishman who is coming to dinner this evening,”

he said, “This morning I treated his arm after a shooting accident and his name is Winston Churchill”. Mother would recount how the two small girls were ushered into the room, and there was Winston, his arm bandaged and pleasantries were exchanged before the girls were hurried off to bed. It was a small incident, though it was one that she never forgot, and her only meeting with the great man.

In 1910 it was decided that the family would move from Turkey to London for the children’s education, and the doctor also wanted to modernise his surgery, and accepted an appointment at Westminster Hospital. Mother recalled the train arriving at Victoria, from where they drove off in a carriage to Ladbrooke Grove where the family had rented a large house. A young lad helped load the carriage with all their belongings, and then ran alongside it all the way to their house, and helped unload it all. Grandfather gave him a florin for his help, for which he was deeply grateful. It was an eye opening introduction to the state of poverty in London at that time, and the desperation people would go to just earn something.

The two girls were then put into a good Ladies College, Tudor Hall at Chislehurst Kent, which was close to London and not too big and impersonal. There they remained until grown up and they became in due course great friends of the Inglises who had started the establishment. At the school when they arrived there were a fair number of Irish girls, both Catholic and Protestant who spent endless hours bickering and arguing with one another. Mother would recall that she was completely and utterly mystified as although she was from a Protestant family most of her friends were Catholic, as was the convent that she had previously attended. She used to say in later years that the arguments were incomprehensible when she was ten years old, and were equally so when she was 90!

It was at Tudor Hall that they made great friends of the Yarrow Shipbuilding family from Scotland, who had two daughters Gwen and Mary. They had a large mansion at Bickley near Bromley, and also another at Brechen near Montrose in Scotland. There they would meet with the other brothers, Goodwin, Teddy, Ronald and his twin sister Kathy who at that time were both in their infancy. The family was very artistic, Gwen was an excellent artist with a beautiful talent for line drawing, whilst Mary was more musically inclined. Like Madeleine and Helen they were all very well read, and so there was in Ladbrooke Grove especially, but also at Bickley a constant stream of artists, musicians, actresses and writers. They were all encouraged by the doctor, who was himself also extremely well read, and a great historian to have a very intellectually stimulating life. Later Mother was to get increasingly involved in social work in London with Gwen helping distressed families, where the major problem was endemic drunkeness through a constant supply of cheap alcohol at any time of the day. So it was that when Father made his way to their address in Ladbrooke Grove, to meet up with friends from Turkey, he automatically got involved into a very intellectual and artistic milieu. From a rather raw colonial background, he now was getting involved with a highly educated and avant-garde set. He was of course taken with the two sisters, but Madeleine was engaged to Goodwin Yarrow with whom she had known for years, and with so many others at the house, father was just “one of many”. However they both agreed to correspond with him when he went to the front, as their way of helping the war effort, and he later found in these letters a wonderful companionship in all the future hardships that he was to undergo.

|

|

Chapter 4: THE FIRST WORLD WAR

|

It was now time to commence training with the Artist’s Rifles and after only the briefest he was off to France to an area near Ypres. Here he was to spend the next appalling six months, in the cold mud, rat invested trenches with only occasional brief respites for recuperation back from the very front line. Fortunately he did not suffer like many others from a gas attack, but there was constant shelling, and machine gun fire. He was absolutely petrified to his core, and like so many others who were mere cannon fodder, was just waiting his turn to die or be so maimed that one was sent home, but yet hopefully not too severe to be impaired and be a physical wreck ever after. One day a shell burst particularly close and the shock affected his ears badly, and for the rest of his life, he was particularly sensitive to decompression, whether by going to high elevations as was common in Ceylon, or on aircraft, when he would suffer from a ringing in his ears.

On another occasion he would relate was when he was on sentry duty with strict instructions not to let anyone through the barrier who did not know the current password or who had a written authorisation. A large car drew up and he stepped forward and asked the officer for his permit or password, which he declined to produce.

“In that case I am very sorry” he replied to the rather smart officer, “I have instructions to deny you access”.

“Oh don’t be such a bore fellow.....just go to your Sentry Office and I am sure they will let me through”

He marched to the office, and informed the officer in charge of the position, who then walked out to the car saluted smartly and he then turned to father and said:

“You Bloody fool Charnaud, this is the Prince of Wales!”

One day after six months in France, amongst the squalor and mud however, a loud voice rang down the trench that he was in:

“Anyone here speak foreign languages?”

“Yes I do” He replied.

“What are you fluent in?”

“French, Greek, a fair bit of Turkish and a smattering of Italian”.

“You’ll do. Report to base and you will be off to Blighty.”

With that one brief conversation, he was through the good fortune of his childhood cosmopolitan upbringing, released from the fear squalor, mud and misery of the trenches, and almost certain death, to undergo a three month officers training course at Cambridge University at Girton College which had been commandeered for military training. He spent many happy hours making maps around Granchester, and soon after that was commissioned as an Intelligence Officer, (acting Lieutenant) and assigned a post with the Derbyshire Yeomanry and sent out to Salonika, on the Balkans front. This was the most remarkable break in his fortunes, and for the remainder of the war and for a year afterwards, he had a most interesting and educative time, with a whole host of amazing experiences.

One of his first assignments in Salonika was to discover how there was a leak of information through the lines to the Germans who were allied to the Bulgarians. There were a number of coincidences that shipping was being lost to enemy submarines which happened to suddenly appear just at the right time as the vessels were leaving port. After making many inquiries suspicion eventually fell on a Moslem Hodja, (who calls the faithful to prayer from the minaret). He was thoroughly interrogated, but continually protested his innocence and there was just not enough firm proof to establish his guilt.

Eventually Father was exasperated and took the man for a final meeting up into the mountains. They walked slowly for some hours climbing steadily upward through the rocky slopes until eventually they reached a small coll, when they stopped to rest. It was miles away from the town and completely isolated and silent save for the wind and the distant tinkling of sheep’s bells.

“I have brought you up here where it is quiet and silent”, he said. “There is no-one else here, not a soul; only you, me and God”.

With those words, he simultaneously drew his revolver and from point blank aimed it at the man’s head.

“You will tell me how the information gets through, and if you co-operate I will see that your life is spared, as I will have you classed as an informer and collaborator. If not I will shoot you dead here and now, as I am not going back down the mountain without the information and you alive!”

He released the safety catch and was counting to 5 when suddenly the Hodja broke down, and pleaded to be spared.

“Come I will show you how the messages are passed.”

They walked on further with the Hodja leading the way until a while later they arrived at a rocky outcrop and on the side he rolled a stone away to reveal the post-box with a letter inside from the Bulgarians. He was as good as his word, and saw the man’s life was saved and the British were for a while able to use this knowledge to their advantage.

Whilst working well away from the front he was able at odd moments when there was time in the winter to go shooting for partridge and woodcock in the fields and hills. He had a pointer dog for retrieving and setting up the birds which was a pleasant and loving companion to accompany him. Often he would be billeted in small Greek villages amongst the peasants and by being absolutely fluent in Greek, was able to derive a lot of useful information and help build up networks of informers. He was always fascinated by their industriousness, and the hard life they led, growing vegetables and corn, and from the meagre resources, what good tasty meals they could produce. They were always toiling, in spring setting out their crops, in summer harvesting, in the wet autumn gathering mushrooms off the hills and fields which they would dry in the air on threaded strings. It was interesting also to him, that on their simple diet of vegetables, and minimum meat, how healthy they were and to what a great age they would reach.

One day he had to go back to base and was given £100 in gold sovereigns (About £10,000 today) to pay informers and people who were useful to the allied cause. To get back towards his location he managed to hitch a lift with some soldiers in a truck to a small station where he could pick up a train which would take him on his way. They arrived at the halt, parked their vehicle and proceeded to have a coffee at a nearby cafe whilst they were waiting. Some of the men got out a pack of cards and started playing as they they relaxed in the warm spring sunshine. They were mostly not joining the train but were en route to another destination. Eventually the slow chugging train appeared and they bid farewells with the dog following on board. The train drew out and some five or ten miles later Father found to his horror that with all the banter and chatter, he had departed without his haversack which had been left hanging in the back of the truck with all the gold sovereigns.

There was nothing to do but to jump from the moving train and get back as quickly as possible. It was travelling slowly at about 25 mph or so, and as it approached a slight bend there was a grassy reedy patch, and so he jumped, and rolled down the bank with the dog following after him. Although a bit bruised he was none the worse for wear and a few hundred yards away was the main road back to where he had started. As he reached it he vowed that he would commandeer the first vehicle that came along whatever it was. Soon there was a cloud of dust with a large car approaching, and he stepped out raising his hand.

“In the name of General G.F. Milne I am requisitioning this car to take me five miles back to the station” he said to the driver, suddenly noticing to his horror that the man in the rear seat was none other than the Colonel of the adjoining regiment.

He was absolutely livid and spluttered with rage wanting to know what was the reason, why he was dishevelled; why he had a dog with him, and would have him reported for gross insubordination and see that he was court-martialled. Anyway he got his lift, and to his great relief, the truck was still parked outside the coffee house, and the men were still playing cards, so he was able to retrieve his haversack safely. He never heard anything more about the court-martial.

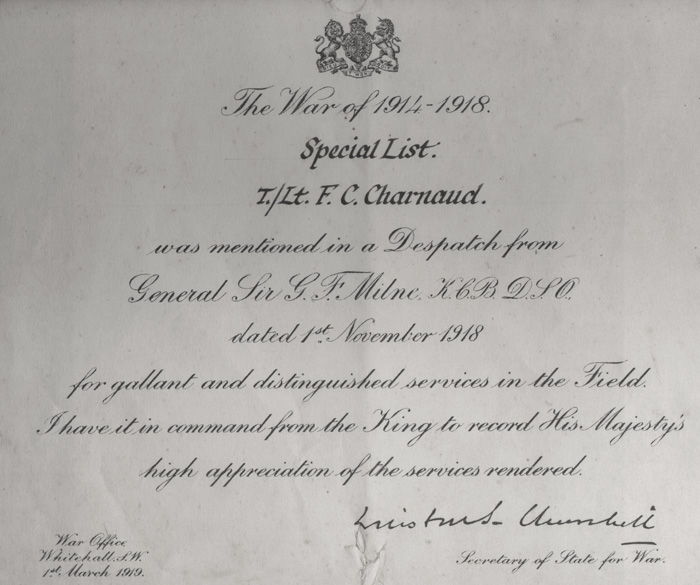

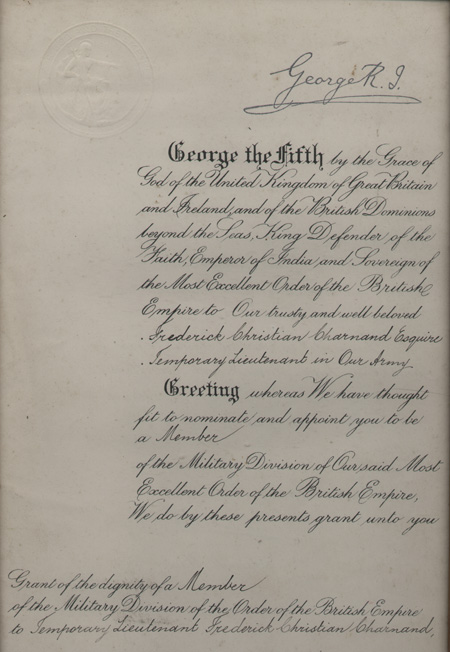

For his efforts in the Balkans he was mentioned twice in despatches, which he rated the biggest honour. The citation for each was signed by Winston Churchill as Secretary of State for War. He was also awarded the OBE Military, the citation states:

“GEORGE the FIFTH by the Grace of God of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and of the British Dominions beyond the Seas, King Defender of the Faith, Emperor of India and Sovereign of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire to Our trusty and well beloved Frederick Christian Charnaud Esquire Temporary Lieutenant in Our Army reeting whereas We have thought fit to Nominate and appoint you to be a member of the Military Division of Oursaid Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, We do by these presents grant unto you Grant of the dignity of a Member of the Military Division of the Order of the British Empire to Temporary Lieutenant Frederick Christian Charnaud”.

|

He was also awarded by George 1st of Greece “de Chevalier de Ordre Royale”.

|

Towards the end of the war his rank was raised to Temporary Captain and shortly after the Armistice he was sent to Turkey to assist in the demobilization and surrender of the Turkish Army. He was now back in Smyrna but instead of the insecure and apprehensive that he had been when he had left, now he was a Captain in the victorious British Army that had made a base there.

|

One of his jobs was to take a small squad of about a dozen British soldiers and set up a base in the interior about 200 miles away close to a railway line in the small town of Afyon. He made friends with the mayor and over the next three months rifles, field guns etc. where brought in a steady stream back to his base without any trouble whatsoever. Everyone was extremely courteous, and Father whose knowledge of Turkish had been limited, had now started to become fairly fluent in a colloquial sense. Eventually after about three months, it was arranged that a train would be sent from Symrna to load up and transport all the weaponry. The rifles had all been stacked in great square piles, and the soldiers were all eager to leave as they would then be on their first stage back to England and demob.

The evening before the train was due to come in there was a knock on the door of his office and he was met by the Turkish Mayor who as usual in his courteous manner inquired after his and his men’s health. They had a coffee together and after all the pleasantries had been exchanged he lent over and said,

“We have greatly enjoyed your stay with us this past three months, and we will be sorry when you go, as you and your men have all been polite and cheerful and we have all worked well together. Now however I have to say, that we forbid you tomorrow to load these weapons onto the train. If you do so, we will have no alternative but to massacre you and your men. It suited us to have the Army demobilised, but now we are going to have our own revolution, and these will be required by Kemal and the New Turks.”

He was as he talked courteous but firm throughout, and it was obvious that he held all the cards and that he knew it. Father too had realised he was in a hopeless situation. He had the responsibility of a dozen men’s lives, who had miraculously survived the most horrific of wars, and all they could think of was returning home to their loved ones. So the following day when the train arrived they boarded it alone, without the weaponry. On arrival back in Smyrna, he reported what had happened and said that unless a regiment at the very least was dispatched, there was no possibility of recovering the arms!

Shortly after this he was sent for his final assignment with the army, alone with only his batman for company to the South of Turkey at Side, near Antalya. There a brigade of Italians had landed and were setting up camp. It was his job to liaise with them in order to find out what their intentions were. The area where they landed was in the heart of a fertile plain with a large river supplying water. It emerged through dining in their mess and chatting with the officers, that they were considering setting up an Italian Colony there, following the breakdown of Turkish power, and the power vacuum in their government. Although it was after the war, he still was obliged to censor his batman’s letters. He was a Liverpudlian, and writing home he said, “Darling thank God in a couple of weeks we will be on board ship coming home. Can’t wait to see you again, but after a month with these damn Italians, I warn you that I’ll divorce you on the spot if you ever feed me on spaghetti again!”

As he came back to Smyrna, there he once again met Fred Whittall, who came for a visit to see his family for the first time since the war. They had a welcome reunion. So much had happened in the nine years that had elapsed since he had left Gampaha in 1910. As they chatted Father mentioned in the course of the conversation, that he was thinking of going to South America once he had got demobilized.

On hearing this Fred with his powerful manner, was suddenly transformed from a quiet man, into someone who felt really hurt from the pang of being let down.

“Look here, when you were seventeen your Father asked me a favour to take you out to Ceylon and give you a training and you accepted this offer on the understanding that eventually when I retire you would take over my Luckyland Estate and manage it for me. You gave me your promise, as did Alfred and so you now have at stake both your honour and your Father’s honour to keep to your word and carry out your obligation. This I expect to be done not reluctantly, but actively and honestly with all the vigour at your disposal, and in the full spirit that you both promised when you both gave me that solemn undertaking.”

He now felt ashamed at even having thought of the idea of South America, and also he felt bad that he had to accept without any answer the full logic of Fred’s position. There was no alternative but to apologise then and there for the thought he had expressed, and to be a big enough man to accept that he had committed a serious error of judgement which was a slur on himself and his father Alfred.

“I am extremely sorry for the thought. Yes of course we owe you this debt of gratitude especially for what you have done for me personally. As soon as I have returned to England and have got demobilised, of course I will return and look after Luckyland Estate for you”.

With that they shook hands, and he caught the boat back to England. He travelled first to Marseilles and then by train to Paris for a couple of weeks enjoyment, as he had been given an introduction to meet up with the famous French Actress Mistinguet. They got on like a house on fire and had a brief whirlwind romance, a pleasant diversion after the long hard war. Then it was back to England and the final demobilization in December 1919.

It was now possible to once again resume contact with the two Chasseaud daughters and to hear at first hand all their news. They had been corresponding fairly regularly all the time that he was away in the trenches, Salonika and in Turkey after the war. Now after his clear intention of having to return to Ceylon, he was determined that this was the occasion to have the companionship of a wife to accompany him to his new home at Luckyland. The problem was that he was equally friendly with both sisters, and so it was a question of choice.

During the war Helen had become a nurse, and was very involved in hospital life particularly tending the many wounded soldiers with horrific injuries. Helen had a rounded face, an extremely quick repartee and a very sound earthy practical common sense that she had learnt from the Greek maids in her father’s household. Madeleine on the other hand had the most beautiful face with the most classic features. In every way she shone from her intellectual brilliance, from her golden hair, her looks, her commonsense and her wide circle of contacts. However she did have a more difficult manner and was not nearly so down to earth as her sister. She had been engaged to be married to Goodwin Yarrow, but he became just one of the many casualties of the war. She found life at home difficult as she was irritated by her Mother who had very domineering and exacting in her Austrian way.

There were constant arguments, and this was exacerbated by her Mother not allowing her to join up, as she said that she required some company and help at home particularly as her father the doctor was working so hard.

During the first part of the War he was based at the Greenwich Seaman’s Hospital where he performed almost non-stop operations. Barges and ships would draw up at the Hospital entrance on the River Thames, and disgorge their loads of poor wounded souls for treatment. It was a never ending task for all the surgeons like himself, who worked and worked with very little in the way of respite. For the latter part of the war, with his knowledge of languages he was transferred to Egypt where he joined the staff of General (later Field Marshall) Edmund Allenby. The only photograph we have surviving from the First World War is one taken at Jerusalem of my Grandfather Major Henry Chasseaud RAMC, General Edmund Allenby, and Brigadier A.P. Wavell (later to be Field Marshall and Viceroy of India).

Father after many deliberations decided eventually to propose marriage to Madeleine. He was enamoured by her beauty and quieter character as opposed to Helen’s greater vivaciousness which he felt would possibly overpower him. Some thirty five years later he was to confess to me his son, when I too was choosing a wife, that the choice he made was the biggest mistake of his life! Madeleine for her part was just one of just so many girls after the war who had little chance of finding the right man due to a million young casualties from the trenches. The scale of the loss of young blood is hard to comprehend today, but one only has to go to any small country town to see their local memorial to their sons that fell so tragically and uselessly. She knew little of Fred when she accepted his offer. He was good looking, intensely ambitious, had a very distinguished war record, and without any formal education had carved a good position for himself. She was absolutely desperate to leave home and the domineering clutches of her Mother, and although she had been warned that the Charnaud family were fairly eccentric, she felt that she could handle this well. The thought of going out to the colonies did not initially pose too much of a problem, in spite of her very sophisticated background, as she always felt she could order such books etc. as she wanted to be sent abroad. So with all these contrary thoughts, some nice, some a bit apprehensive, but above all the release to the freedom of her spirit, she accepted his offer.

The Doctor and his wife Helen, and Madeleine at the beginning of 1920 journeyed back to Smyrna. Sister Helen meanwhile was still nursing, and likewise found the difficulty of meeting the right man. She eventually just after the War met a New Zealander who had come to join the Royal Flying Corps. His name was Frank Harris who came originally from a distinguished old English family from the Cotswolds. After the War he studied Architecture eventually qualifying in his profession. He too was a difficult character. On the one hand he was most charming, and amusing at a party and also most convivial. But on the other hand he was one of those rare people who are intelligent yet have the innate ability to rub their colleagues and seniors up the wrong way.

At the beginning of 1920 Father took the train to Trieste where in the most severe winter weather he caught the boat for Smyrna where he was to get married.

Chapter 5: LUCKYLAND IN THE 1920’s

In January 1920 in Smyrna my Father and Mother got married and immediately after set sail for Alexandria and from Egypt they would get a boat to Ceylon. The journey of a week to Alexandria was no problem, but once there they had endless difficulty trying to obtain a passage eastwards. Fortunately Mother’s uncle Irwin de Kramer was working at the time in Alexandria, so he was able to look after the young couple and eventually after a month of waiting they finally got a small cargo boat from Port Said to Colombo. Whilst in Egypt they discovered that the wedding in Smyrna was not recognised by the British Authorities, so they had a second civil marriage recorded by the British Authorities there.

In Smyrna meanwhile, whilst all this was going on, Grandmother Helen was getting worried with no news as the months passed, and eventually decided to visit a known Greek medium. She went unannounced to the lady’s house to find her on her hands and knees washing the marble floor. She looked up at Granny and said,

“I was wondering when you would come. I know what you want to ask me about. It is about your daughter isn’t it? Well I can tell you immediately she is safe and well, that she is on a second ship, and she is pregnant. But I also see her going to a strange house with lots of little round things all around the house and these I do not know what they are?”

With those few prophetic words she just continued her work on the floor!

After a brief stay in Colombo and a visit to the offices of the new managing agents: George Steuart & Co. they took the train upcountry. The experience for Madeleine was mind blowing. First there was the intense humid heat and the lushness of the low country, with its myriad palms, bananas, brilliant flowering yellow cassias, vivid red flamboyants, and cherry blossom pink tabebuas. It was April and the hottest season but also the most beautiful for the magnificent flowering trees which burst into bloom at that time of the year like a tropical spring display. Soon though they left all this behind and they were at last at their destination at Luckyland Bungalow perched on the side of the range 4,750 ft. high with the slopes at the end of the garden dropping away 2,000 ft. and then rising slightly to reach the Welimada plain. All around as described before were ranges of hills in the far distant circling the plain to give one of the most spectacular views imaginable. The air was cool after the sweltering sticky low country and in the shade never rose much above 70 F at midday. The sense of arriving at last at ones journey’s end, and free from the rigours of life at home with all its petty irritations was the greatest relief of all.

The bungalow that Fred Whittall had built was enormous with a 120ft [36 m.] central corridor from which led off about 6 enormous bedrooms, a vast drawing room, and an equally large dining room and central leading onto a patio was a morning or day room. Either side of the building were two vast open verandas for plants or for sitting in the cool. There was a well-stocked vegetable garden, but otherwise everything as was usual in those days was very primitive. There was no running water, servants brought jugs etc. to the bedroom. Toilet facilities were a “thunder-box” and a goodly supply of sawdust.

The roof was covered in red painted corrugated iron, which was the most efficient way of holding out the tropical downpours, but when it rained with a heavy tropical “plump”, the noise was deafening, and it was almost impossible to carry out a conversation, with the vibration overhead. Luckyland had an average rainfall of about 120” per year and some wet years half as much again.

Apart from the primitive state of the bungalow the Estate was only just coming into proper bearing and was only yielding about 350lbs of made tea per acre. The Estate, since his time at Gampaha had been formed into a Limited Liability Company and half the shares had been sold to a man called Gordon on the nearby Rappahannock Estate. With the proceed s of this sale a factory had been built at about the highest point of the estate (5,000 ft.) nestling under the lee of the Buffaloes Hump the rock face of which rose sheer for 700 ft. above. By the time they had arrived to take over the property, old man Gordon had died leaving his shares equally to his seven children, most of whom had a weakness for drink or other vices. There was one sound son Hugh, who in the preceding few years had slowly acquired from most of his kin their shares, and he also looked over the interests of the rest. It was at his insistence that the agency was moved from Whittalls to George Steuarts, and he was not only a director of the Company but also acted as its “Visiting Agent” making twice yearly detailed visits, with recommendations for improvements to the property.

Shortly after father’s arrival Hugh Gordon paid him a business visit and it was the start of a life-long friendship, and business partnership. Each were very different men. Whereas father was quick dynamic with a boundless energy and impetuous to get things done, and always find a way round a problem. Hugh by contrast was quiet and thoughtful, and working as he did on the other main tea growing side of the island, he was able to pass on new ideas which he was always on the lookout for. He was a pensive man in contrast to his ebullient Australian wife Dorothy who in turn was a quick tongued ball of fire. They never had children but their marriage was an eternal love match to the very end.

By far in a way the most serious aspect of their situation was that the estate was so small and the yield so poor with a result that the profitability was only barely marginal. It was sufficient to barely keep a bachelor, but for as for also having a well to do wife who was pregnant with all the added expense, the financial implications were very worrying. Socially too conditions were difficult. Most of the senior planters in the district came from well-off middle class public school educated families, with usually either themselves or their wives having a private income. There was a tremendous degree of snobbery at the local Dickson’s Corner Club, as was the case in most of the other upcountry clubs. Tea planting in those days was a job for well-educated and well-connected people in much the same tradition as an army regiment. In fact the whole operation on an estate with its hierarchical structure, was organised very much on military lines, with very similar chains of command. Also there was in those immediate Post War Years a tremendous camaraderie amongst those who had come back from the terrible war. Conversely people of fighting age who had as they said “funked it” were completely ostracized. The Patterson brothers next door at Allagolla fell into this category and were made to feel very ill at ease for years and years. As Father had not only done his bit, but was also highly decorated he was regarded and honoured with the greatest respect by all his peers in the district.

As they were literally tied to the job by “the debt of honour” there were three possible ways of improving the situation. One was to raise the yield and the output of the property; second was to see if it was possible to enlarge it by buying more land. Thirdly there was the chance of starting one’s own estate by buying up virgin land and planting up a new property, but the problem here was again money.

Over the next three years a start was made in each category. By sheer hard work, and reading agricultural books, the yield soon started to rise. Secondly he was able to acquire from a Tamil for the company 150 acres of very poor tea on steep, dry quartzy soil at a lower and hotter elevation, to create the new Napalbokka Division of Luckyland. Thirdly he approached Hugh Gordon about coming in with him on the proposed new estate, and he agreed, and Fred Whittall also agreed to lend him the money for his share at the usurious rate for those days of 8%. Another bonus also came with the offer from the Comte de Luppe to overlook the nearby Downside Estate about which more will be said later.

So after a shaky and a rough beginning financially, slowly things began to improve. In October their first son was born and named after Hugh Gordon. Mother now was over the first six months gradually getting to grips with her situation. First she had to learn Tamil to be able to communicate with the servants both inside and outside the house. She was a quick learner but like most people occasionally there were absolute howlers, with calamitous but amusing consequences.

For example one afternoon she asked the boy to “bring the bath to the bedroom”. In those days there was no running water, and hot water was heated in an oil barrel with firewood and carried in to fill freestanding bath. She waited quietly in the morning room for him to call her when it was ready, when she suddenly heard a terrific noise of horses hooves and clattering harness. She rose and went into the passage just in time to see the harnessed horse being led into the bedroom.

She inquired what on earth was he doing and then she eventually realised the mistake she had made. Instead of using the word “coothilee” for a bath, she had by mistake used the word “Coothiree” for a horse. The simple estate Tamils could never understand the extraordinary wants of the English anyway. “If Lady wants a horse in the bedroom, it’s none of our business, she can have it all harnessed and ready to go!”

Another day not long after they arrived it was decided that they would have as a special treat, a roast chicken for Sunday lunch, so at the beginning of the week whilst they were working out menus, she told the cook. A few days later, Father told her that he had an unexpected guest coming on Sunday for lunch and she had better check on the size of the chicken to see if it were large enough. She went out to the kitchen at the back of the bungalow and asked the cook the same question, and he immediately rushed out with a mammoty (Digging Hoe) and started digging away in the vegetable garden. She followed him curiously to ask what he was doing and he replied,

“Lady wanted to see the chicken, and I am getting it for you”.

“But why have you buried it?” she inquired.

“Old Master (Fred Whittall) always had his chickens buried for at least five days before, so as to make them tender and tastier”.

Catering in the out stations was always a tricky business, particularly in the days before the first refrigerators came out. At places at High Elevation with the cooler air the problem was less acute, but in the low country with temperatures in the 90’s food deteriorated quickly. Each week a boy would be sent to the nearest town with a large tuck box and a shopping list for beef, whisky, HP or Worcester sauce and various groceries. In the Low Country the beef would be eaten hot roast the first day, thereafter one day cold, and then it would be reheated and soused in sauce to disguise the flavour as it rapidly went off.

At Luckyland there was no need for quite such drastic action, but the same regime of a weekly beef-box continued up to more or less the present day. In 1926 Father purchased what in those days was unheard of a “Frigidaire” refrigerator which ran off paraffin and it was still in use some 40 years later, testimony to the solid engineering of an early model created before ideas such as “built in obsolescence” became the vogue!

Mother found to start with the constant even temperature of 70 F [21 C.] and used to long for an English winter, although during the rainy North East Monsoon, the house would get penetratingly cold and damp, and fires would be lit in the sitting room to give cheer and warm the place up. In April and May (the hot season) she would slip into her swimsuit and run up and down the lawn in the rain when there was a big midday thunderstorm. She was very secretive about this, and never told Father who she feared was rather prim in these matters!

About six months after they had been at Luckyland, she laid out on the bed some pairs of shorts and long socks.

“Look what I have bought for you to wear round the Estate. You will find them far cooler for walking around instead of your long cotton trousers. It is becoming the fashion and you will be far more comfortable!”

“Do you honestly think that I can go around the Estate like that showing off my knees. What would the coolies think? They would burst out laughing at me!”

Eventually after a long argument she was at long last able to persuade him that the dress was quite seemly and soon everyone would be the same when working on the Estates.

But dress codes were very severe. It was not until 1932 that after a stormy meeting at Dickson’s Corner Club, it became possible to wear white shorts for the annual tennis meet. In the evening most elderly planters from the pre-war days would change into evening dress for dinner, even when by themselves. The interwar generation compromised with a dark blue blazer and tie. Of course on the ships going back and forth to England evening dress was mandatory until the last night on board, when rules were relaxed.

In early 1922, two years after Hugh was born, Mother had a welcome visit from her Mother, who came out to see just where she was living and the sort of life that she was leading. At the same time that she was there her sister Helen and her husband Frank the architect, had also decided to come out to Ceylon and wanted to stay at Luckyland and “creep” with Father. He had not been progressing well in the large firm that employed him in London and both felt that the opportunities and good life of Ceylon would be preferable to the drudge of working in England. The company of Helen was pleasant, but Frank was very difficult as he was one of those men who after half an hours training, reckoned he was more expert than the expert! Tensions arose with Father who took a dislike to Frank, who in a minor way started to cause discord in the house, which from very small beginnings at first, would sadly and steadily increase and cause a severe strain on the marriage.

|

|

|

|

|

|