Sydney La Fontaines Carpet Warehouse and Depot written by Taylan Zeybek and translated from the Turkish by Görkem Daşkan, 2012 |

|

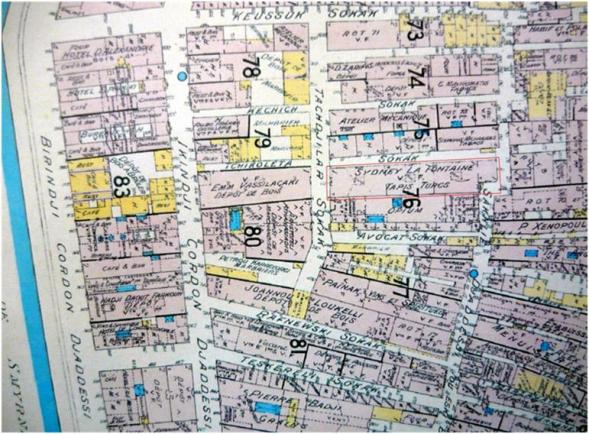

The building investigated in this article is situated in what is known as the ferhane district in Ottoman Izmir. This district was surrounded by the Second Cordon Street to the west, Frank Street to the east, Sarı Sokak (Yellow Street) to the north and the Arabian Market to the south as of late 19th and early 20th century. Some researchers note that the word ferhane has derived from the word barhane which meant the depot of buildings like caravanserais and inns. The ferhanes of this area were narrow, passage-like sites connecting two streets and filled with shops lined up side by side on one or both sides. Having gates at both ends, ferhanes were generally covered above with wooden boards or vine branches. Therefore, ferhanes used to generate a dim atmosphere in their interiors. Their state of being dimly lit and the fact that the word fer meant daylight or brightness in Persian (hane means house or place) might also have led to their being called as such. The development of the area dates back to the early 17th century. Whereas in the early stages of this development, it was mostly storage warehouses that were erected, later with the arrival of merchants from Chios, retail trading was added to their list of functions. The heavy demand in the area and further space requirements were to culminate in the filling up of the inner harbour. In the 18th century, inns as workplaces (han in Turkish) were built in the vicinity of ferhanes which acted like rows of shops of the same trade in an Ottoman bazaar but mainly acting as storage warehouses. The streets between the ferhanes which were built in a long and narrow style intentionally on the sea-front so as to benefit from the harbour most efficiently by many, acted like hans as well, having loads of shipped goods stored within these. In the 1830s, some of the piers on the Coast Street were already filled and in 1875, after the quay was constructed with infilling, the area became too far from the seashore and thus lost its importance. Following this period, the product stored in the area included mostly tobacco, timber, dried fig and raisins, acorns, wine and carpets. The depot (or a warehouse) belonging to Sydney La Fontaines carpet company, one of the leading carpet traders in and around Izmir, stands out as a good example of the workplaces of the area.

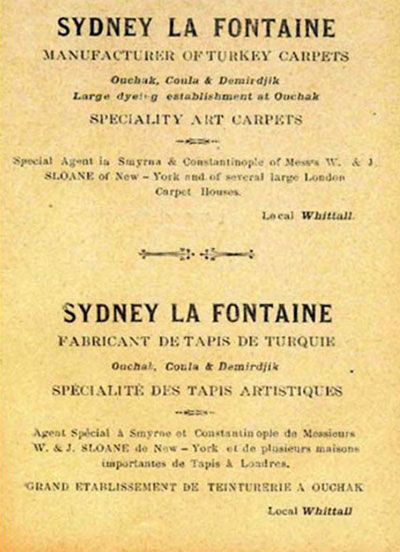

At the time, weaving of carpets, rugs and prayer rugs -three of the traditional export products of Izmir- was a home based industry that spread to the smallest settlement in the region. Woven at handlooms generally by village women at towns like Gördes, Kula, Uşak, Demirci, Eşme, Takmak and Milas; carpets, rug and prayer rugs were transported to Izmir and then exported abroad. Until the 1860s Turkish tradesmen had control of this business in Western Anatolia by way of giving the villagers the order of production. The entry of foreign capital into the carpet sector started with English capital after 1864. Three English merchants provided some of the carpet weavers in Uşak with threads and patterns and then exported the product. The English, slowly but surely, became the leaders of the carpet industry and monopolized that trade in the region. Domestic employment, as a post-European Industrial Revolution phenomenon, had been well accepted in Western Anatolia and brought about high profit rates without requiring big and constant investments. The English merchants who kept control of the production of carpets for the following 30 years showed no effort whatsoever for a transition to industrial scale carpet manufacturing. The carpet industry, apart from the few existing mills and factories established for the purpose of the spinning and dyeing of yarn, was based on solely domestic production. An Austrian company (Keun and Partners) who found the English merchants production technique not sufficiently advanced opened a carpet weaving factory at the turn of the 20th century in Uşak. Employing 80 workers at the time, the company had 12.000 square meters of carpet woven per year. The Austrian companys profitable success encouraged the opening of 15 more carpet companies that same year. The Turkish and minority1 carpet traders had not managed to build a network of production and distribution over the years as wide as that of the English traders. These companies were only able to operate in regions exempted from the English traders reach but still had to buy the yarn from the English factories. This was pushing up their costs of their manufacture. The English merchants figured out the risks of their own monopoly that they have previously acquired, so as a precaution, they established an associate company investing a start-up capital of 400.000 pound sterling. In 1913, this company was the sole company in Turkey to manufacture and export carpets. Established in 1908, the Oriental Carpet Manufacturers Ltd., consisted of the following six nominally English companies: P. De Andria and Co. founded in 1836, G.P. and J. Baker founded in 1878, Habif and Polako founded in 1840, T.A. Spartali and Co. founded in 1842, Sykes and Co. founded in 1902 and Sydney La Fontaines company which is the subject of this article, founded in 1880.

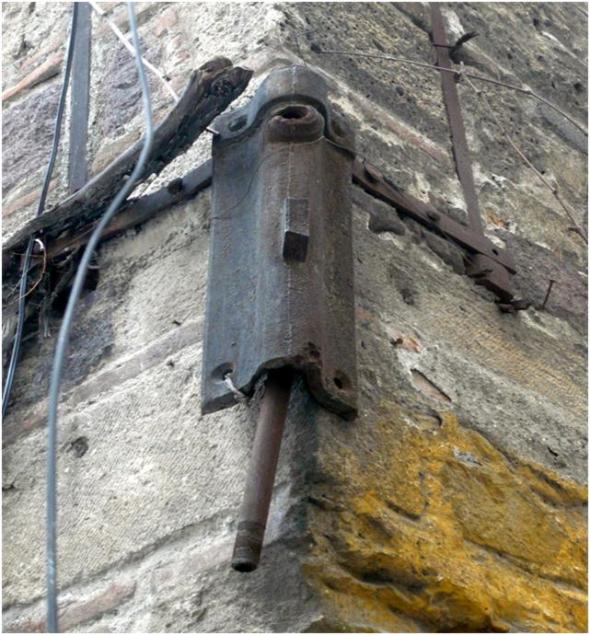

James La Fontaine was the first La Fontaine to come to Izmir. Born in Geneva, Switzerland, James, had been sent, at a very young age, to his maternal grandfather Isaac Morier in England and had become an English citizen after having lived there for seven years. James was one of the merchants with the Levant Company of England and after arriving in Izmir in 1786, he had established a company with Edward Hayes. Having married a Venetian lady named Maria Cocchini della Grammatica in 1797, James became the father of nine children by the time he passed away in 1826. One of his children Edward La Fontaine was the father of Sydney James William La Fontaine born in 1846. Being a partner of J.W. Whittall and Co. and the shareholder of 30 percent of its stock, Sydney established a carpet company in 1880. The company had the carpets produced at Uşak, Kula and Demirci. They had a yarn dyeing factory in Uşak. The oldest advertisement we have found of the company dates from 1895. Other ads dating 1896 and 1898-1899 were found in the commercial guide of each of these respective years. The head office of the company was in Izmir and its address was reported to be Local Whittall. According to the Goad Fire Insurance Plan of 1905, the place bound by Taşçılar (Stonecutters) Street to the west, Sahil (Seaside) Road to the east and Çikolata (Chocolate) Street to the north seems to be the carpet depot and warehouse of Sydney La Fontaine. The construction date of the building (1895) is compatible with the advertisement dates, however, we have no clue of the exact date the workplace opened its doors or where the companys former workplace used to be. It is again unknown, whether the family owned the place post-1905, when the Oriental Carpet Manufacturers Company was founded, or if it was sold off. We suspect, though, that the depot has been in use for a long time. The masonry of the building is a typical example of the periods depot architecture. In the Goad Plan, it looks like the main entrance of the building faced west in the direction of Taşçılar Street, which makes sense, as the western facade of the building is more elaborate than the eastern side. The eastern entrance to the building seems to have partly lost its originality as a result of alterations. The western entrance to the building used to be a two-winged iron door with an arch over which vertically aligned bricks were placed in such a way to impose less weight on the door and give the building a more aesthetic look. The arch windows were decorated in the same manner. The construction date of the building is indicated above the main door: 1895. We can see the same writing on the eastern facade, albeit more subtly. On the western facade, above the door, there is a pediment ornamented with dressings and a small round window right in the middle. There are small round windows also on the facade facing Çikolata Street. Another small round window can be seen above the main door and all of them are decorated with iron profiles. The arch windows on the facades facing Taşçılar and Çikolata Streets are protected with double iron shutters. The saddle roof is clad with Marseilles terracotta tiles and the three roof lanterns were installed to provide additional daylight into the building. When looked at below the roof line, the traces of the original plaster that came off can be seen. This plaster used to give the exterior walls a rich ashlar look but in time as it has peeled off the stone underneath is now visible. This building, built for the purpose of storage of goods was owned by a family who once lived in Izmir. Çikolata Street, Sydney La Fontaines carpet depot and a few other depots in the area that developed from the 17th century until the fire of 1922 are a few of the rare cultural properties that survived the fire and managed to remain intact over the years. This building, laying at the intersection of Şehit Fethi Bey (to an extent, former Sahil Road), 1349 (Çikolata Street) and 1347 (Taşçılar Street) Streets, serves as a carwash today.

References:

1) Çınar Atay, Osmanlıdan Cumhuriyete İzmir Planları (From the Ottoman to Republican Periods: City Plans of Izmir), 1998.

2) Çınar Atay, Kapanan Kapılar İzmir Hanları (Closing Doors: Historic Commercial Buildings of Izmir), 2003.

3) Melih Gürsoy, Tarihi, Ekonomisi ve İnsanları ile Bizim İzmirimiz (Our Izmir with Its History, Economy and People), 1993.

4) Osman Öndeş, Asıl Efendiler Levantenler (Levantines: The Honoured Gentlemen), 2010.

5) Abdullah Martal, Değişim Sürecinde İzmirde Sanayileşme 19. Yüzyıl (Industrialisation in Izmir in the Period of Change 19th Century), 1999.

6) Orhan Kurmuş, Emperyalizmin Türkiyeye Girişi (The Import of Imperialism into Turkey), 2007.

7) Levantine Heritage web site.

Biography:

I was born in Konak, Izmir in 1986. My father was trained as a textile designer though he mostly worked in the private sector and is now retired. I have a younger brother who is a student at the Ege University fisheries department. I graduated in turn from the İnönü High School in 2003 and in 2010 from the archaeology department of the Dokuz Eylül University, with a group first. I was involved in excavations at Smyrna (Bayraklı) in 2007, 2008 and 2009, Nif (Olympos) in 2010. I was amongst the first volunteers for the Katakekaumene Burnt Country Geo-park Project in 2009. I was involved in the surface investigations of the Likya Region Roman period road network project. I am currently (2012) doing a masters at the archaeological department of the Dokuz Eylül University and continue assisting at the Smyrna (Agora) digs.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|