The Interviewees

Interview with Michael Refalo - January 2023

1- The 1917 census of Egypt shows a substantial population of ‘British subjects’, presumably the huge majority were Maltese clearly outnumber the British from the UK. Did the Maltese community have their institutions apart from the British / Italians, such as their own churches, clubs, schools, post-offices, banks etc.?

The Maltese in Egyptian centres tended to congregate in particular areas of the larger cities. Despite their relatively large number, they were far fewer than Greeks and Italians and hence tended to congregate in areas occupied also by these latter. Nevertheless, networks of association which privileged intercourse between the Maltese themselves, were established even if their very residence ‘among others’ necessarily entailed the extension of such networks beyond strictly national nodes. Furthermore, the Maltese community in Egypt was neither rich enough nor did it receive any substantial assistance from home. Unlike the Italians and the Greeks whose social, religious and cultural institutions were subsidized by the home country or by the more affluent, the Maltese were relatively poorer. This meant that the Maltese could not have the educational, religious or cultural institutions that the other settled migrants had. Nevertheless, the Maltese managed to form a number of ‘Maltese’ institutions in both Alexandria and Cairo. Although these were mainly of a religious bent (e.g. the Confraternity of Our Lady of Mount Carmel in 1854, attached to the Church of St. Catherine in Alexandria), others had philanthropic (e.g. the Maltese Benevolent Fund in Cairo and a similar institution in Alexandria both constituted in 1880), cultural (e.g. philharmonic societies set up in 1896 and 1918) aims. On the other hand, however, the Maltese did not have their own churches (but they did have their preferred ones), post offices and banks. In so far as churches were concerned, St. Catherine mentioned earlier was the one most favoured by the Maltese. The Church had received donations from the Austrian Emperor in 1833 and 1850 and was assiduously frequented by both Italians and Maltese. Indeed, in 1842 when the church was being rebuilt following an earthquake, some ‘respectable Maltese residents in Alexandria’ requested financial assistance from British imperial funds. Lord Stanley, then Secretary of State for War and the Colonies seemed inclined to acquiesce, with two provisos, namely that the number of Maltese in Alexandria should first be ascertained and that the funds would come out not of imperial funds but from Maltese coffers. This example is perhaps indicative of the differences in attitudes and action between British subjects born in the UK and Maltese British subjects. As for post offices, the Maltese being British subjects could make use of the British ones. The same cannot be said for banks, the more popular with the Maltese being the Imperial Ottoman Bank, the Credit Lyonnais and, to a much lesser extent, the Banco di Roma.

2- The Maltese community in Egypt seems to have been very adaptable and making use of work and small business opportunities. Do you put this down partly to their British based education which presumably they received both in Malta and Egypt if they were not first generation?

Many of the original Maltese migrants to Egypt were far from being educated. Indeed, most were illiterate. It was only with the second and third generation of Maltese in Egypt that started obtaining a sound education. Lack of literacy, however, was never the same as ingenuity and adaptability. Many of the Maltese who migrated to Egypt were skilled craftsmen who took advantage of the progressive policies adopted by Mohammed Ali and his grandson. These rulers sought to modernise the country and in so doing provided work for carpenters, builders and other craftsmen of whom a good number were Maltese. Others migrated to Egypt and other North African ports in the hope of obtaining that which was not available for them in Malta, namely, work. Of these, some were successful but others fell by the wayside.

Insofar as education is concerned, the Maltese mainly attended Italian schools. The reason is religion: both at home and abroad the Maltese were wary of Protestant proselytizing and hence preferred Roman Catholic institutions rather than British ones. There were also attempts to set up Maltese schools. One such appears to have been in existence towards the end of the 19th century in Alexandria. There was also a girls’ school run by the Franciscan nuns in the same city and yet another taking around 20 students in Port Said. It would appear that most of these small schools catered for middle class students rather than the great mass of lower-class migrants’ children. In the 1920s, in Port Said there was an attempt to acquire land to build a school for Maltese children by the Maltese Community in Port Said (said to have been the oldest Maltese community in Egypt). With the assistance of the Egyptian Government, the land was acquired but by 1929 it became evident that there would not be enough funds to build and eventually run the school. The end result was that enterprise was taken over by the Residency with the end result being that the school became a mixed one named ‘The British School’ with the administration being in the hands of a committee of which only half of the members were Maltese, the other half being British.

3- To what extent did the Maltese community in Egypt intermarry with the various other migrant communities and do you think this was a major contribution in creating a community with very little nostalgic connection to their ‘home’ country? Did this also contribute to the loss of the Maltese language amongst the second and third generations and which languages became their ‘at home’ language?

Contrary to the Italians who preferred to marry within their own community, the Maltese seem to have had no prejudice against marrying Italians, Greeks or other nationalities. Rather than nationality, it would seem that social position, religion and perhaps financial advantage lay at the basis of marriage strategies. There do not appear to have been problems with marrying Italians and Greeks. Less common were marriages to British spouses. A niece of Roberto Stabile, reputed to be very rich, married an Englishman and lower down the social scale we encounter a Maltese named Emma Grech whose married surname is Roberts as well as Lucretia, another Maltese, married to a John McCuish – both definitely not Maltese!

Of course, offspring from such marriages tended to lose their Maltese language. But this happened also with second and third generation Maltese who would have retained, perhaps, a basic knowledge of Maltese but would become well versed in French, Italian or English.

Until the last decades of the 19th century, Italian was widely used in Egypt; French was also common particularly within the bureaucracy and English was the language of the virtual masters of Egypt, particularly after 1882. However, it is worth noting that the Ottoman Orders in Council acknowledged the profusion of languages in Egypt, even in so far as British subjects were concerned, Thus, for example, the 1873 Order provided that documents issued by the Consular Court had to be either in English or in Italian whereas documents submitted to it could also be in French. This was obviously a move to cater for Maltese British subjects for whom Italian was a second language. In time, of course, English became more widely used but the different languages clause was retained in the Order in Council of 1899.

As for the loss of the Maltese language because of marriage to foreigners, this might have been a contributing factor. However, by the time of the second and third generation Maltese, integration within the wide migrant community and beyond necessarily weakened the links with Malta, language included. As a spoken language within the family it was most probably retained but social intercourse would be carried out in other languages. Inevitably much of the Malta language was lost.

4- You note that on the same street you have observed Maltese citizens living next to local Egyptians, Syrians, Italians, Greeks and others, showing clearly mixed neighbourhoods. What was the source of information on this spatial data?

The main source for my book Among Others have been the records of the British Consular Courts of Cairo, Alexandria and Port Said found at The National Archives (Kew).

When analysing these documents – voluminous as these are – one finds that apart from the predictable evidence of disputes, petty and serious criminality, probate and similar topics, there is a deeper layer of evidence which throws light upon daily life in Egyptian cities. Since the Maltese were British subjects, their complaints, their prosecution in case of crime, their death and all their ‘official’ and ‘public’ affairs came up before the Consular Court. It is, however, beneath that surface, more precisely in the evidence given by witnesses, in the description of the circumstances attending a fight, a theft and a murder, in the inventories of deceased Maltese that one discovers how the Maltese (and with them others) lived their daily lives. This evidence clearly shows two things which are apparently contradictory but in truth are not.

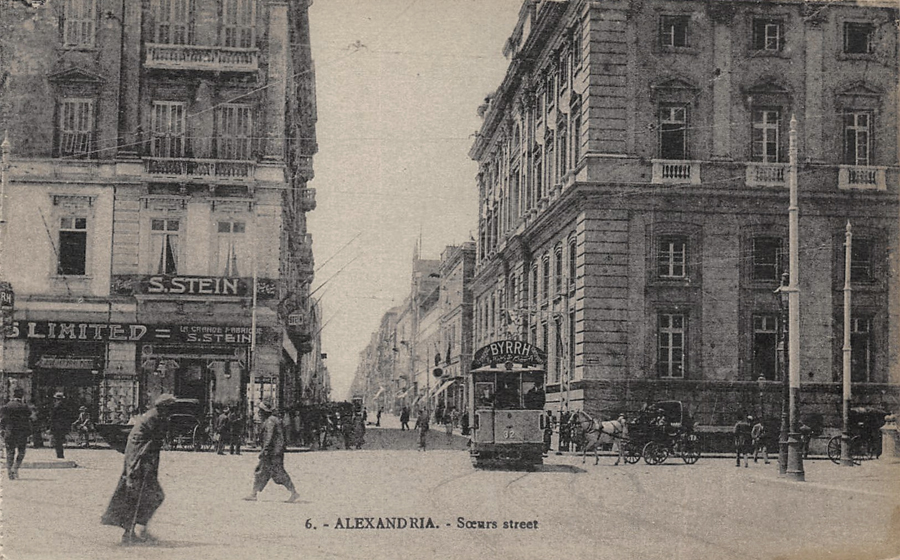

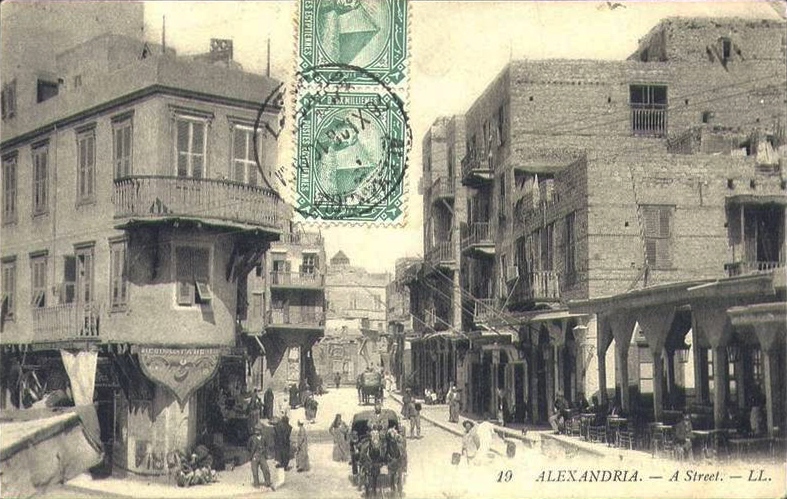

First of all, the Maltese (and this includes not only first-generation migrants) tended to inhabit particular areas of Cairo and Alexandria. In the former it was Bulaq, a once-flourishing suburb but later on a centre for the lower tier of migrants; in the latter it was the Labban Quarter, particularly the Rue des Soeurs and surrounding area. This might lead one to imagine the Maltese in a closed community. However, this was far from being so. In the same areas where the Maltese congregated there also congregated other migrants coming from the north, south and east shores of the Mediterranean. The evidence submitted by witnesses found in the records of the British Consular Court clearly shows that these ‘foreign’ communities not only lived side by side with each other and with the local population but were also in constant contact, established networks and had daily intercourse with and between them. The evidence emerging from the records of a deceased Maltese shop keeper whose drawer was full of coins of a substantial number of currencies, as mentioned in the book, is illustrative of this close contact.

5- For the Maltese who were British subjects, property ownership was based on Egyptian law. Was this the same for those Western power countries who might have benefitted from Ottoman capitulations or did this privilege not apply in Egypt? Or was there a ‘pick and choose’ option open for some where convenience dictated where mixed-marriage links allowed?

Property ownership by foreigners in Ottoman lands was allowed after the Sultan’s decree of 1856. While the Capitulations remained in full force, property ownership was subject to the local law at least in so far as the payment of taxes was concerned. This was the case with all foreigners and not the British only.

It is interesting to note that despite problems with land ownership prior to the 1856 decree, there were Maltese in Egypt who, prior to that date managed to acquire property. As early as 1835, one Maltese was suing an Italian national for the payment of rent. The proceedings in this case took place before the Neapolitan Consular Court. However, as was proper practice, the British Consul would have been kept abreast of the case since the person prosecuting was a British subject.

It is also worth mentioning that the Maltese, at least those who could afford it, were keen property owners. Like their counterparts in the Maltese Islands (perhaps of a later generation), those Maltese who could afford it sought to acquire property in Egypt for investment purposes. Indeed, a good many continued living in rented premises, preferring to rent out the properties acquired.

Of course, the problem of taxation could cause problems for property owners. One Maltese whose family had originally migrated to Algeria but subsequently settled in Cairo managed to acquire as much as 600,000 square metres of land. However, in the acquisition of some of these properties he encountered problems with the Egyptian authorities who, at times, refused to register the land in his name and at others insisted on payment of tax. This individual’s eventual acceptance to pay the tax contrasted with the claims made by other Europeans who claimed that no tax should be levied on their properties in view of the Capitulations.

The Maltese, of course, were far from being the only settled migrants to acquire property in Egypt. Indeed, the major property owners appear to have been the Greeks. Just one example suffices: Etienne Zizinia, member of a family that had had been close collaborators with Mohammed Ali, was the first to purchase land at Ramleh, a district of Alexandria which later became one of the more fashionable areas of the city.

6- Roberto Stabile was described as the richest British subject in Egypt who died in 1914 with a substantial fortune. Do we know how he made his money and was any of this inherited from his father?

Unfortunately, I have not been able to trace the origin of Stabile’s money. However, it would appear that at least a part might have been inherited but the more substantial share was definitely due to his commercial acumen and the subsequent shrewd investments which he made.

The fact that Stabile might have inherited some of his wealth is substantiated by the fact that a brother of his, Antonio, though not in the same league as his brother, was also quite affluent. However, in Antonio’s case it does not appear that he was commercially involved. Practically the whole of his assets consisted in investments in bonds, shares and bank deposits. This might seem to point to inherited rather than acquired wealth, but of course, without supporting evidence from the primary sources, this cannot be confirmed.

It is, however, relevant to note that Maltese migrants during the 19th century – whether originating from Malta or from other Mediterranean ports – rarely, if ever, settled in Egypt with their purse full. Money was made in Egypt not elsewhere, and almost certainly not in Malta. As for the Stabiles there is evidence that a family of that surname was resident in Smyrna (Izmir) but they were far from rich … but more research is required for anything to be written …

7- In 1956 when the Maltese had to leave Egypt with the Nasser revolution the Maltese government would only accept those born in Malta. Do you know why they took that firm line?

The answer can be given in just one word: overpopulation.

During the 19th century and well into the 20th, Malta’s problem was perceived to be the high population density. This was, of course, true. However, underlying this assertion was the fact that Malta, a British colony, was perceived to be first and foremost a ‘fortress colony.’ Hence, too many people within the fortress were, potentially, a problem. This narrative was adopted also locally because of the dearth of natural resources, and the heavy local reliance on commercial rather than industrial activity on the island. The only large employers were the government itself and the British navy and docks.

It had been the policy of the government of Malta to encourage emigration to mitigate the problems connected with lack of employment opportunities, indigence, as well as crime. At the same time, however, migration was not an organised affair and all 19th century attempts to organise it came to naught. Since the preferred destinations for the Maltese migrants were cities on the Mediterranean littoral, including Alexandria, Cairo and Port Said, whenever problems arose in the host country, a quick return to Malta was available. This occurred, for example, in Egypt in 1882 in the aftermath of the bombardment of Alexandria.

Migration of indigent Maltese, however, did not entirely solve the problem for the Maltese government. Indigent Maltese in Cairo, Alexandria and elsewhere sought assistance (and, less often, return) or required medical assistance. These needed to be paid by the home government. In view of the considerable number of such requests originating from the various host cities, the Maltese government took the view and adopted the policy of assisting only those Maltese who were born in Malta. Second and subsequent generations of Maltese were thus in an almost ridiculous situation: they were British subjects on the strength of their Maltese parentage, but they were not Maltese on the strength of their own birth.

In 1882 when a large number of Maltese escaped to Malta, the government had no option but to accept and accommodate them, secure in the knowledge, however, that these would eventually leave Malta. In 1956, the situation was different. There was no prospect of return to Egypt and accommodation of a large number of ‘Maltese non-Maltese’ would have been financially and socially detrimental to the Maltese Islands. Incidentally, the same had happened earlier when Maltese migrants and their successors left Izmir in 1922.

8- Have you been able to reach out to Maltese families who used to live in Egypt and make use of any of their records and photographs?

Unfortunately, no. However, my book and the research leading to it stop comes to an end in 1923 so it is most unlikely that there are still alive any survivors from that date. Furthermore, the sources available have been overwhelming. It has taken me five years of research and elaboration of the date to be able to obtain as clear a picture of the life of the Maltese in Egypt during that period.

At the same time, it is my ambition to attempt a continuation of the story even if this has been covered by other historians who have followed the Maltese to France, Australia and elsewhere after 1956. In particular, Andrea L. Smith and Julia A. Clancy-Smith have exhaustively dealt with the subject. Locally, a descendant of those migrants, now living in Australia – Nicholas J. Chircop – has contributed also to the subject.

Despite this, time and pressure of work permitting, I would like to pursue the matter and make use of interviews, records and photographs as well as other sources connected to the period after 1923.

9- There was a Maltese newspaper in Port Said, run by Giovanni Said, ‘the Chronicle’ and perhaps others. Were you able to see copies of this publication and do they give any sense of the local community and their businesses through adverts etc.?

I was not. I suspect however that such a source as the newspaper in Port Said but also other written primary sources would be particularly fruitful should the story of the Maltese in Egypt be continued from 1923 to 1956. The newspapers as well as other personal memorabilia from the descendants of those who left Egypt in 1923 should act as supplement for the lack of British Consular Court records. These latter start thinning out after 1923 in view of the tumultuous conditions obtaining in Egypt immediately before and after independence.

Of course, the perspective which would be envisaged from these sources would, at least in some ways, be different from that resulting from the records prior to 1923. Whereas the latter has privileged Court documents, the former would, arguably, provide a more sentimental, nostalgic view of the life of the Maltese in Egypt. In any case, primary sources whatever their nature, are vital for our interpretation and portrayal of the past.

10- There was a Maltese newspaper in Port Said, run by Giovanni Said, ‘the Chronicle’ and perhaps others. Were you able to see copies of this publication and do they give any sense of the local community and their businesses through adverts etc.?

This does not appear to have been the case. There is, however, one exception, lamentable as this could be.

In 1914 the British authorities in Malta (with the blessing of the local Archbishop) expelled from Malta a firebrand by the name of Manwel Dimech. After some time in Italy, Dimech found himself a prisoner in Egypt. He died there in 1921 having spent the last years of his life in a lunatic asylum.

In Malta, Dimech was a firebrand, advocating the independence of the Maltese Islands and other radical ideas which grated with the sensibilities of both Governor and Archbishop. He was branded a criminal (he had indeed been one in his youth), a freemason, a Protestant and a heretic when in truth he had acquired an education in prison and used his talents to teach, write and edit a newspaper in the vernacular. Once expelled from Malta, Dimech was egregiously treated: a prisoner of war kept in prison and lunatic asylum, even after the end of the Great War, to be buried in an unmarked grave somewhere still unknown.

Apart from this lone individual there do not seem to have been a Maltese ‘literary circle’ in Egypt. Nevertheless, this does not mean that there were not individuals who achieved an advanced level of education. One such was Pierre Cachia (1921-2017) who attained the position of emeritus professor in the Department of Middle East Languages and Cultures at Columbia University and taught Arabic at Edinburgh University.

11- What are you working on right now?

There are a number of strands which I am trying to pick up. Most of these have emerged from my research into the lives of the Maltese in Egypt, but there are also others. My ultimate aim is twofold: to try to retrieve enough information to be able to continue the story of the Maltese in Egypt after 1921 but prior to 1956 (after which date they were dispersed throughout the world) and to study the lives of the Maltese in other Levantine centres particularly Izmir and Istanbul.

In any case, I am well aware that the history of the Maltese, whether in Malta or elsewhere is not of particular interest to historians (and book buyers) from other countries. Nevertheless, I firmly believe that a study of such small communities as the Maltese – at home and abroad – is important in order to complete the texture of 19th and early 20th century Mediterranean history. This is confirmed by the studies undertaken during the last decades by scholars as Clancy-Smith, Andrea Smith (both mentioned earlier) but also others including Will Hanley whose book Identifying with Nationality, has been particularly valuable to me in writing my own. Hopefully Among Others will set a course for a deep study of Maltese migration around the Mediterranean.

Postcard views of Soeur Street area in Alexandria early 20th century, an area where many Maltese lived. Rue des Soeurs had that name because at one end of it there had been at one time a nun’s convent but in time, when the nuns had gone, prostitutes moved in!

Interview conducted by Craig Encer