The Interviewees

Interview with Kaleb Herman Adney - March 2022

1- Is one of the reasons you chose this Ph.D. topic the fact that the Ottoman sources for the province of Salonica are complete like those of the Damascus province?

Salonica and Damascus both have incredibly rich archival collections thanks to the hard work of a handful of dedicated archivists in both places. I am not sure the status of archives within Syria given the ongoing conflict but a number of brilliant historians have written about Ottoman Syria using these sources. I believe that copies of many, if not all, have been preserved in Istanbul. The Salonica records have not been as widely used by researchers and this was one of the things that piqued my interest in them upon first exposure. I still struggle to understand how such a rich collection of documents has been used by only a handful of historians.

To answer your question more directly, I did not initially choose to write about tobacco because of the collection in Thessaloniki, Greece (i.e. the administrative headquarters for the Ottoman province of Salonica). I had a long-standing interest in tobacco as an agricultural product as it offered a window into the process by which the eastern Mediterranean was integrated into the global economy. The extensive collections of material on tobacco in Istanbul largely revolve around the Régie Company after its establishment as domestic monopoly-holder in 1883. Because I quickly became enthralled with the networks of tobacco merchants who were largely independent from the Régie or who actively opposed its policies, I began to dig into provincial records to understand more clearly the relationship between the various local, regional, and international networks operating in Salonica, Kavala, İskeçe, etc. The Salonica commercial court records have been a godsend in this regard as they demonstrate the massive discrepancy between the idealized way that the Régie was meant to function and the way that many different social groups actually experienced its establishment and operations. The regional perspective offered by the commercial courts, in other words, demonstrates how international finance and the Ottoman dynasty still had to contend with factors of political economy in the provinces (such as long-established commercial networks and the interconnected market imperatives related to finance, exports, and industry in places like Kavala, Drama, and İskeçe).

There remain many aspects of the commercial court collections that I explore further in articles that I am currently writing as well as future research projects on inheritance, financial instruments, and bureaucratization in the late Ottoman Empire. These sources are obviously not limited to what they can tell us about the commercial networks of tobacco merchants. They reveal a number of other aspects pertaining to the key position of Ottoman institutions within the historical expansion of capitalist market relations in the Mediterranean — an aspect of this history that is often neglected in studies of global economic integration.

2- Have the records of other Ottoman regions been lost through the ravages of war?

Although the court records in both Damascus and Salonica have certain gaps for unknown reasons (perhaps related to the regional instability both before and during World War I), the collections of both nizamiyye and şeriyye court records are more complete than most of the Ottoman provinces, at least to my knowledge. In the case of Salonica, these court records are complemented by bank records and various private collections. This is both a blessing and a curse given that the sheer volume of material available on the province of Salonica has, at times, made the research process slow-going. It is very hard to say what happened to records elsewhere in the empire as it largely depends on the context but, in short, atrocities committed by nationalist movements and invading armies included the ransacking of administrative entities (at least in the Balkans). However, many of the archival losses can be attributed to more ‘benign’ forces such as inclement weather, flooding, fires, and the ever-present desire amongst collectors to turn a profit off of antiques and valuables.

3- The dominance of the tobacco trade in Macedonia and Thrace must have evolved gradually along with expanding producer networks and infrastructure which facilitated the provision of quality products to Western Europe. Do you think local political administrators were a minor player in developing this infrastructure (i.e. provision of seed, sourcing of new fields, warehousing and processing etc.)?

This is an excellent set of questions. Although it is difficult to surmise whether Ottoman bureaucrats and administrators ultimately hindered or harmed the tobacco trade, it is worth exploring these questions for the insights they provide both into the history of tobacco and the possibilities for research on Ottoman political and economic institutions.

It is easy to look at the Ottoman tobacco trade and assume that the policies of the Sublime Porte were ultimately responsible for undermining its profitability both before and after the declaration of Ottoman bankruptcy in 1875. After all, tobacco revenues were incorporated into the realm of international finance on the premise that the industry would be more productive and profitable under international supervision. At the same time, the tobacco trade became a desirable source of revenue for the Ottoman Public Debt Administration and the Régie Company precisely because of its huge potential. This evaluation was based on the higher value ascribed to “Oriental” tobacco in European markets in relation to tobacco grown in Central Europe or the Americas. A German-language newspaper from 1884, for example, estimated that at .93 Austrian florin per kilogram, tobacco from the Ottoman domains was worth nearly triple that of French tobacco and over quadruple that of Austro-Hungarian tobacco. Ottoman cultivators were clearly harvesting loads of high-quality tobacco and in the Balkans prior to the involvement of European financiers and the Ottoman Public Debt Administration.

Although I am not saying that the value of this tobacco was necessarily the direct result of an intentional Ottoman policy, I don’t believe the old narrative that the Ottomans failed to develop the tobacco trade prior to its incorporation into the realm of international financial control.

Instead, I think that both the central government and provincial Ottoman administrators showed preference towards the tobacco merchants who supplied international markets, especially those in Central Europe. This shaped the Ottoman tobacco trade as predominantly an export industry, at least in the southern Balkans. This ultimately contributed to the profitability of tobacco in Macedonia and Thrace and created a long-standing business culture that challenged Régie hegemony over the raw material, infrastructure, and supply chains of tobacco exporters from the mid-nineteenth century until well into the period of Greek rule. Merchants with market networks in the Austro-Hungarian domains, in particular, won out in the long-run. The most prominent among them were the Allatini Brothers, M.L. Herzog, Hermann and Charles Spierer, Juda and Semtov Perahia, among others.

As for the development of infrastructure, it might be useful to take each example you gave in turn. Firstly, to my knowledge Ottoman administrators did not provide seed to cultivators at any point in the nineteenth or the twentieth centuries. According to Murat Birdal, the Régie Company occasionally did provide cultivators with seeds when it supported specific goals such as eliminating low-quality tobaccos on the market. Generally speaking, however, high-quality tobacco cultivation in Macedonia and Thrace was akin to other artisanal endeavors — peasants and merchants meticulously selected the most flavorful and productive plants for seed. Those seeds largely remained within the personal and market networks of merchants and cultivators rather than being centrally administered. Archival documents from the 1870s demonstrate that merchants in İskeçe (contemporary Xanthi) shared seeds with cultivators in Izmir in order to advance the relatively underdeveloped tobacco market there. Likewise, Mary Neuburger shows that émigré peasants from Ottoman domains preserved seed in Bulgarian agricultural cooperatives ultimately serving as the basis for a robust Bulgarian tobacco trade in the late Ottoman and post-Ottoman period. In this sense, seed preservation seems to have been more of a grassroots effort than an organized policy.

Secondly, tobacco fields became an object of strict regulation under the Régie Company after 1883. Cultivators were not allowed to grow tobacco on plots that were less than half of a dönüm and, as a result, the number of registered tobacco cultivators diminished in actual terms and as a result of growth within the black-market tobacco trade. This makes it difficult to determine what lands were used for tobacco cultivation to begin with. It is clear that most land used to cultivate tobacco was not provided to peasants as part of a broader stimulus project. There remains a great deal to be explored on this point, however, and I hope to find more sources on the role of mültezims, or tax farmers, in this context. I have written a bit on the role of specific mültezims in the tobacco industry and their role in undermining merchants by demanding excess customs payments and the like. I still don’t have a great deal of information on the ways that landowners (either of large çiftliks or small plots) actually transformed their holdings into tobacco farms although I hope to revisit this question in future. Any thoughts on this or suggestions for further archival reading from your readership is most welcome via the e-mail address I have provided below this interview.

Lastly, warehouses are yet another thorny issue in the history of Macedonian and Thracian tobacco. To my knowledge, the Ottoman government never built warehouses for the merchants, cultivators, or corporations involved in the tobacco trade. The Régie Company, however, was responsible for providing warehouses in cities and villages with a sizable share in the tobacco trade. Cultivators and merchants, for their part, were to deliver their tobacco to these warehouses either to be sold to the Régie Company for the domestic market or to be inspected prior to export via non-Régie parties. A few notable merchants with connections in Austria-Hungary, however, managed to secure the right to use their own warehouses for storage prior to export. In 1909, Louis Rambert (the director of the Régie Company after 1901) described in detail how this had become a source of tension amongst tobacco merchants in Macedonia and Thrace who saw this as evidence for corruption. From the perspective of Rambert, however, this was merely a practical exception since the export companies in question were well-established suppliers for the Austrian tobacco monopoly and could not reasonably move the massive loads of their tobacco to other facilities for inspection. Instead, Régie inspectors, as the more mobile party, were supposed to visit their warehouses. I have written an article which is forthcoming in an edited volume dedicated to the memory of Turkish economic historian Mehmet Genç; if anyone is interested in delving deeper, they will find that article on my academia profile once the proofs have been sent to me.

Well into the Greek period, tobacco warehouses remained a point of contention. A 1926 article in the Xanthi newspaper Yeni Adım, for example, describes the short-sightedness of cultivators who over-planted their fields while last year’s crops lay in warehouses unsold due to economic instability throughout the country. Can Nacar and Juan Carmona-Zabala have both written excellent articles on the role of the Ottoman and Greek states, respectively, that showcase the conflicts between market-conscious export merchants and their peasant suppliers whose labor was often under-appreciated or neglected completely during times of economic duress.

From a German-language collection of postcards from the 1930s detailing the stages of production within the tobacco industry from field to factory and market.

4- Was the Ottoman government more concerned with taxation and combating smuggling? Did this change over time?

The Ottoman government and the Régie both were concerned about smuggling throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Smuggling remained an issue even after the Balkan Wars, as numerous consular reports attest. However, in the years during and after the First World War, the concerned parties ultimately changed for obvious reasons. This led some merchants with Central European connections to emigrate to avoid political or economic liability under the new circumstances.

I am personally interested in smuggling for two main reasons, neither of which are quantitative in nature. First, I see smuggling as a window into the conflicts between various parties involved in the export industry as outlined above in my discussion of warehouses, cultivation, and the like. Second, I seek to understand the ways that smuggling came to be and how its meaning was contested. These issues are obviously intertwined and are mutually supportive of one another — merchants-cum-smugglers reveal the logic behind regulation of the tobacco trade while simultaneously underlining the many limits to international finance within Macedonia and Thrace. What emerges from my analysis of smuggling is the agency of tobacco merchants and cultivators who either openly rejected the title of smuggler imposed on them by others or embraced it by operating in the shadows. There is extensive evidence for both responses within commercial court records, petitions, Régie reports, consular records, newspapers, and proceedings recorded during financial policy conferences held in the region.

Smuggling occupies a very large part of my dissertation and an article which is currently under review. I will limit myself to this brief response for now in hopes that the interested reader will find answers to questions about smuggling in my written work.

5- The credit market seems to have been markedly unstable in the Ottoman Empire, particularly before the late 19th century. Private lenders, however, were clearly very active in the Ottoman domains throughout the nineteenth century. Lending money is a risky business in any domain and presumably even more so in a zone of ethnic and national tensions that finally burst with the Balkan Wars. Do you think the Ottoman state had an uneasy and suspicious relationship with local creditors particularly since the sultanate itself was in debt to European financiers and it was clearly in no position to offer a viable financial alternative?

You are right that credit was fraught with all kinds of political, economic, and social issues. The fact that lending was risky business is clear from a number of archival documents in the late 1870s and early 1880s. During the late 1870s, some of the merchants with more liquid assets worked as creditors while continuing to trade in agricultural and industrial goods. During the 1877-1878 Russo-Ottoman War, the relationship between creditors in Salonica with clients and business partners in Bulgaria was partially severed due to the political upheaval which accompanied the establishment of the Principality of Bulgaria. This made it difficult, if not impossible, to recover debts owed well into the 1880s. That said, this is another reason why the commercial court records of Salonica are an archival goldmine.

Court records demonstrate that even in these difficult circumstances, internationally recognized legal institutions like the courts and their underlying legislative apparatus were relatively successful in settling accounts and facilitating financial agreements between debtors and creditors. This is important considering the “backwardness” often ascribed to the Ottoman Empire and offers a challenge to the notion that Ottoman institutions were largely ineffective and underdeveloped. So much for the first part of the question.

As for the second part, financial histories of recent years have clearly demonstrated that the Ottoman sultanate was in a disadvantaged position vis-a-vis the European financial system. However, there are also a number of reasons why contracting loans with European creditors was beneficial to Ottoman development projects such as the expansion of its military and the spread of its railway system. See, for example, Ali Coşkun Tünçer’s excellent work for more on this. Such logic also explains to some extent why the Ottoman Empire declared bankruptcy and handed over the administrative reins of many of its revenues to the Ottoman Public Debt Administration. This move allowed the empire to continue borrowing on the international market and to expand its developmental programs. This does not negate the fact that the Ottoman Empire was in dire straits in 1875 and was largely at the mercy of its creditors, but it does allow us to understand some of the ways that the empire worked towards its long-term developmental strategies in spite of these circumstances.

You are right to point out though that the state itself was not in a position to offer much in the way of alternatives to the credit systems in the provinces. In Salonica, credit was bifurcated between regional lenders and international finance. Both offered formal credit through established banks including the Imperial Ottoman Bank, Banque de Salonique, Banque d’Orient, National Bank of Greece, and the Agricultural Bank. There were also a number of “informal” credit mechanisms offered by non-institutional actors largely, if not entirely, belonging to the “regional lenders” category rather than the “international finance” category. Because of this bifurcation of credit in Salonica, I think that Ottoman institutions like the commercial court and the public notary largely served to arbitrate the credit relations of these actors. I have no strong conviction that such arbitration reflected anything beyond these institutions’ basic function. If anything, the Ottoman government (both the central government and the provincial administration) was supportive of local efforts to formalize the banking sector by establishing a local branch of the Ottoman Bank there and hosting the Banque de Salonique headquarters in Istanbul, for example. I am certainly open to the idea of an “uneasy suspicion” as you say but, at least under Abdülhamid II, this does not dominate the provincial documentation that I have seen.

6- In 1883 the Régie Company was created by three separate European banks (with German, Austrian, French, and British financing) to manage a monopoly on the domestic tobacco trade. As part of that agreement did the Ottoman government receive much needed funds or were these profits completely gobbled up by the Debt Administration that was tasked to collect all such income? Can we speculate that these foreign financial investments in all these different spheres were fuel to the flame in terms of rising Turkish nationalism?

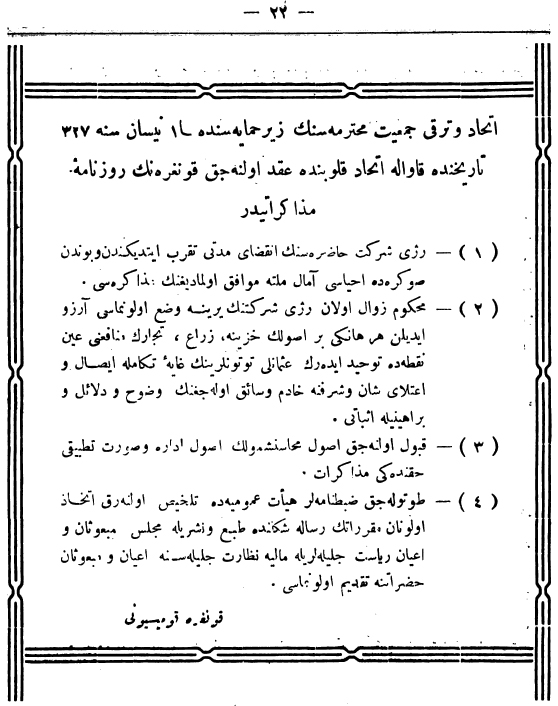

This question serves as the backbone for an article I have written and which is currently under review. Hopefully, once it is published, the relationship between Turkish nationalism, the concept of an Ottoman “national economy (milli iktisat),” and tobacco in the Balkans will be a bit more clearly enunciated. In short, on the eve of the First Balkan War a movement opposing Régie policies was quite active in cities such as Kavala, Drama, Salonica, and Pravişte (not to mention the Anatolian cities where similar movements developed). The participants framed much of their efforts in terms of the national will and the economic development of the nation but they were by no means all Turkish nationalists. Many of the most active among them were Greeks and Jews. Although with the violence that accompanied the period between the 1890s and 1920s (and especially the ethnic cleansing which took place during and after the First World War) it is easy to assume that political movements took on the terms of the various nationalisms with which we are now familiar, there was a much wider spectrum of possibility amongst Ottoman subjects in the final days of the empire. This is one reason why opposition to the Régie Company in particular is such an important subject of analysis. Many popular interpretations of the behavior of merchants, cultivators, and smugglers cast these historical actors in fundamentally anachronistic national terms; their actions instead need to be understood on their own terms if we are ever to have a deeper understanding of the cultural and economic history of Ottoman Macedonia and Thrace.

The issue of profit-splitting between OPDA, the Régie, and the Sublime Porte is actually quite straight-forward. The profits were split between the three parties with OPDA receiving a fixed annual sum of 750,000 Ottoman Lira regardless of the yearly performance of the company. The percentage of revenue that each party received fluctuated according to the net profit of the company. The margin for Régie profits were actually lower than that of the Ottoman government which, when the company did well, stood to gain more revenue as a result. This was a sort of failsafe mechanism that, in theory at least, guaranteed the cooperation of the government.

7- Did extra-territoriality by inference mean that merchants needed consular protection to operate on the trans-regional and international markets?

On a technical level, I am not sure if extra-territoriality has some specific legal definition which requires consular protection. In practice, the merchants who enjoyed extraterritorial status that I discussed in my talk for the Levantine Heritage Foundation and about whom I typically write enjoyed consular affiliation of some sort. As Will Hanley, Aviv Derri, Sarah Stein, and others have so clearly articulated, the implications of and requirements for consular protection, protégé status, and the like changed throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as the political environment transformed. The most prominent merchants that I have come across were typically quite flexible in legal, political, and economic terms. Many Jewish merchants in Salonica or Kavala, for example, enjoyed French or Austrian consular affiliation, but maintained robust commercial ties in Egypt and Anatolia with Greek and Muslim merchants. One such merchant was an ardent Zionist who sought to establish tobacco farming as a viable enterprise in Palestine while another escaped to Germany after the region fell to Greece and Bulgaria in 1912. Likewise, some Christian merchants enjoyed Russian, French, and British consular protection while vacillating between the Greek, Ottoman, and Egyptian commercial realms. To my knowledge, no Muslim merchants enjoyed consular protection but some Dönme (Jewish converts to Islam who followed the teachings of Sabbatai Zevi), such as Hasan Akif Pasha, nurtured their Central European political and economic connections to their advantage even though they were not represented in any formal sense by a foreign consulate.

This complex picture of the relationship between these various political and cultural identity markers is one reason why I use the term extra-territoriality here instead of Levantine. The idea of a Levantine identity is slippery and quite difficult to pin down. If I were to give another talk like the one I gave for the foundation, though, I would confront this issue explicitly by proposing a clearer definition of Levantine than those which are currently in use. On the one hand, Levantine can refer to the geography of the eastern Mediterranean coastline bordered in the North by Turkey and in the South by Egypt and, as such, described anyone residing there. I think this is a useful definition in some cases, but, when applied to that geographic stretch, offers little in terms of clarity and probably makes as much sense as the term Arab, both being essentially umbrella terms for many ethnic and religious groups.

On the other hand, the use of Levantine that your cultural organization tends to rely on is more explicitly oriented towards folks of European lineage residing in the Ottoman Empire. This is a more clear-cut definition in some ways but it is built on a few assumptions that I think are worth reconsidering. Levantines in the Ottoman Empire are generally affiliated with either a political or religious expedition to the Middle East (and sometimes both). The people who we think of as Levantine according to this cultural definition are therefore associated with either Christianity in its various western manifestations or with European capitulatory privileges on the other. Again, there is overlap between these religious and political spheres. The term Levantine is, in this way, somewhat bipolar in that it is supposed to indicate European origin but is often conflated with religious or political affiliations.

Many of the people that I am most interested in don’t quite fit this latter definition. Many of the Jewish merchants that dominated the tobacco industry during the late nineteenth century had a European lineage either from Austria-Hungary, Spain, or Italy; did their Jewish identity prevent them from being Levantine? Others were protégés of Greek heritage who were Christian and represented the consulates of the USA, France, and Russia but had been born and raised within the Eastern Orthodox tradition and may have spoken English and French with an accent; did their lack of European pedigree make them definitively not Levantine even though their political and economic activities – not to mention their commercial networks – fit the bill quite nicely? These are open questions, but I don’t think that creating a textbook definition of Levantine is really the answer to them. In fact, many of the most interesting case studies demonstrate that different ethnic, religious, and linguistic identities did not prevent specific merchants from interacting within a cultural and economic sphere that some, including us here, have begun referring to as Levantine. Applying that adjective to individuals of the late Ottoman period is, at least sometimes, more forced than we might realize. My suggestion here is that ultimately, whether one uses the term or not, they still have a great deal of explaining to do and that begins with stating clearly the decision to apply such terminology ex post facto.

8- Solomon Allatini obtained permission from the Ottoman government to export tobacco to the Austro-Hungarian domains in 1863. Do we know what strings might have been pulled in this instance or was it simply the reflection of the long-standing capitulation privileges that the family had obtained well before from various European powers?

I don’t know and I don’t believe it is possible to know whether there were any “strings pulled” in this case. If I’m wrong, hopefully I will find out by confronting some rich source material that I have not yet seen.

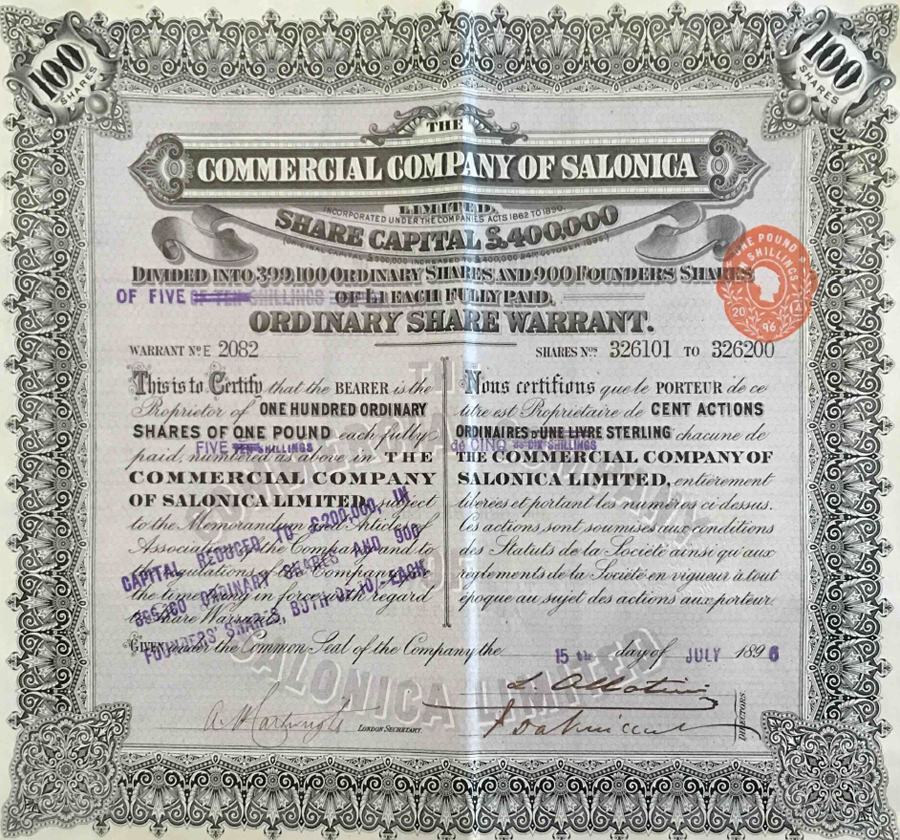

It is hard to say ultimately whether the Ottoman privileges afforded to the Allatini Brothers were a reflection of their reputation amongst the late Ottoman sultans or some other set of factors. To be more clear, it is not easy to determine in which direction flowed the streams of influence: Were the Allatinis considered too valuable as one of the most important industrializing forces and some of the most powerful capitalists in this corner of the empire? Or was the decision to reduce the transaction costs of Solomon Allatini ultimately responsible for his family’s increased significance within local political economy? One thing is for sure, the privileged position of the Allatinis within the tobacco trade lasted for the entire subsequent generation; the privileges afforded them and their various financial and commercial organizations (including Banque de Salonique and the Commercial Company of Salonica Ltd. but also the Société Industrielle et Commerciale de Salonique) by both the Austrian and Ottoman governments were hugely important in this regard. These privileges are detailed in a forthcoming article. I also have plans with a group of like-minded scholars to produce a special issue on the political economy of the late Ottoman Empire which explores the relationship between politics and commerce; my contribution will expand on my current work on the Allatinis to explore their role in interconnected markets of credit and industry, as well as the hugely important role they played in public works projects within the port-city of Salonica.

If any of your readers have primary sources pertaining to the Allatini family, the Perahia brothers Juda and Semtov, the Commercial Company of Salonica Ltd., Charles and Hermann Spierer, the Salonica Cigarette Company, or the Egyptian Cigarette Company, I would be thrilled to connect with them via the e-mail address provided at the bottom of this interview.

An ordinary share warrant for a shareholder in the Commercial Company of Salonica Ltd. printed originally in 1895.

9- The Allatini family set up a branch of their tobacco trade in Egypt under the name of ‘Salonica Cigarette Company’ in the 1880s. Was this in response to early Régie Company policies? Do we know how the other major players in the regional trade, Jack Abbot or others, responded to this new circumstance?

Conducting this interview allows me to clarify portions of the talk that I either explained unclearly or in which I made a mistake. In this case, I made a confusing mistake during my talk. I showed an image of a document that explained the Régie Company’s concern over the tobacco trade with Egypt and the loss of revenue potential there. This was an ongoing concern for Régie officials. I mistakenly said in my talk that this image was of the Salonica Cigarette Company’s establishment in Egypt under Allatini supervision. I mixed up two similar-looking documents.

To clarify, the Allatinis’ decision to establish the Salonica Cigarette Company in Egypt with commercial partners from Salonica was not directly related to Régie policy as it actually took place in 1903. The company seems to have been an expansion of their successful venture in Macedonia and Thrace under the Commercial Company of Salonica Ltd. (the purchasing agent who went to Egypt in 1920 switched between company letterhead from both organizations) and may have been more directly related to higher industrial wage costs and increases in the costs of raw materials during the period between 1880 and 1900.

The direct response to the Régie Company was mixed. For the Allatinis, they were able to secure continued privileges thanks to interventions made by the Austrian government on their behalf. This allowed them to avoid some of the risks and transaction costs that drove so many other smaller merchants out of the tobacco industry in the mid-1880s. For other merchants, however, the response was often quite aggressive both in rhetoric and in action. Many merchants, especially in Kavala, refused to recognize the right of the Régie to control their commercial activities and those who did not turn to direct confrontation refused to cooperate by going underground as it were.

At the same time, a number of merchants, such as the aforementioned Hasan Akif Pasha, actually went to court to manipulate the situation to their advantage and utilize Ottoman legal institutions against the Régie. My research is largely a detailed analysis of what trans-regional networks and local commerce can show us about the failures of the Régie. These various responses provide some evidence for that argument.

An excerpt from the ‘Kavala Tütün Kongresi’ proceedings hosted by the Committee of Union and Progress in Kavala in 1911 on the eve of the Balkan Wars to challenge Régie Company policies long considered bad for business by most Kavala-based tobacco merchants (from the original published proceedings a copy of which is held at UCLA).

10- Clearly the Austrian port of Trieste must have been the primary hub of import of the Kavala and region tobacco. Do we know which families controlled the leg that end. Were there family branches planted there to ease that leg of the trade that you know of?

I wish I had a direct answer to this question; it would be a great asset to have some archival documentation that explains some of the actors on that end of the supply chain. The Austrian Lloyd Shipping Company played a major role in moving oriental tobacco from Kavala to Trieste and I have read some sources in Ottoman, English, French, and German that detail the quantitative data associated with these shipments. Although these are primary sources from the time period in question, they are collections of metadata and give me no insights into the actual labor regimes, insurance schemes, or credit mechanisms used in Trieste. If your readers have any insight on this issue or on tobacco processing or shipping habits in Trieste more generally, I am very open to conversations about it via e-mail.

11- What sort of information and material would you welcome from our readers to help you in your research?

If any of your readers have any information on specific families involved in the tobacco trade in the Ottoman Empire, whether that be a bit of oral testimony or an actual family document, I would be incredibly happy to have a conversation about it via e-mail at ; my interests are quite broad and I would hate to limit myself to the names of individuals and companies mentioned in this interview or in the talk I gave. I am very open and would love to hear from as many readers as possible about their insights whether academic or personal.

Interview conducted by Craig Encer