The Interviewees

Herve Georgelin | Pelin Böke | Alex Baltazzi | Axel Corlu | Philip Mansel | Antony Wynn | Fortunato Maresia | Vjeran Kursar | Christine Lindner | Frank Castiglione | Clifford Endres | Zeynep Cebeci Suvari | Sadık Uşaklıgil | İlhan Pınar | Ümit Eser | Bugra Poyraz | Oğuz Aydemir

Interview with Zeynep Cebeci Suvari, November 2015

1- What kind of education did you have and your general background please?

I was born in Istanbul to a Turkish mother and father. Both of my parents are intellectuals with sufi backgrounds. I have always been interested in other cultures and lives. I studied English Literature for my B.A. Then I realised without knowing much about religion, one cannot fully understand literature. Especially if one considers Literature classics such as Paradise Lost or Inferno, religion is essential to understand and to interpret these works. So I ended up studying comparative religions and philosophy. After graduation I lived and studied in the USA, Syria, Yemen and Italy.

2- What does Istanbul mean to you?

Being from Istanbul is really a great background. Because I feel at home both in the East and in the West. İstanbul has a very rich history, unfortunately today we are losing it day by day and not enough is done to preserve it. We, the Turkish people are very ignorant of our own history. Also history of the land we came and settled means almost nothing to us. This is really sad.

3- How did you end up studying in Italy in 2001?

While I was studying Arabic in Damascus in 1999, I met Paolo Dall’Oglio a Jesuit priest who was running a monastery dedicated to dialogue between Muslims and Christians in a Christian village. I was very impressed by him and decided to study in his university. (Unfortunately Father Paolo has been kidnapped by ISIS and we do not know what happened to him.) At that time Muslim students were unheard of in Pontifical Universities. I did my Masters on Christian theology under the guidance of Prof. Daniel Madigan, another great Jesuit scholar, in Gregoriana University in Rome. I also received a scholarship from the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue and met Pope John Paul II twice. During my time in Rome I studied Latin and church history. Rome is the ideal city to study both of these. This experience also enriched my perception of Istanbul as the second capital of the Roman Empire. Again in Gregoriana and later in Ca Foscari University in Venice, I studied Judaism and Hebrew and befriended a lot of Jewish people. They are/were another important element in the texture of Istanbul.

4- You returned to Istanbul for a PhD thesis at Boğaziçi University. Can you tell us the details of this PhD and how it is progressing?

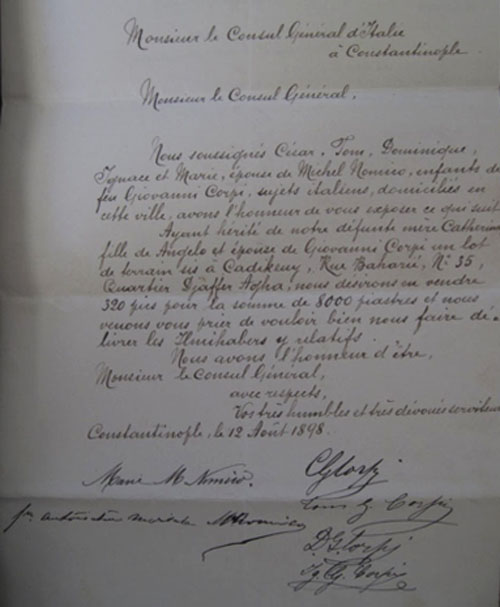

I have been working on my thesis in the department of history in Boğaziçi University under the guidance of Prof. Paolo Girardelli. My thesis title was the Italians of Istanbul between 1870-1910. When I was looking for an original and unexplored topic for my thesis, a friend directed me to a second-hand book seller. He mysteriously acquired thousands of documents that were thrown away from the Italian embassy. I managed to browse and scan some of these documents. But I only opened 7 bags out of the 40 he had in his possession. At that time I thought these documents would be purchased by an institution and become available to researchers. However these documents might be lost forever now. They ended up being in the possession of another book dealer and he refuses to sell or even show them to us. Luckily I photographed some 1200 petitions written by Italian citizens dwelling in Istanbul addressed to the Italian Consul. These pertain to property transactions, such as sales, mortgage or inheritance. On my thesis I built an alphabetical list of these petitions and I am still analysing them in detail.

5- How easy or hard is it to obtain historical information on old properties in Turkey?

It is extremely difficult, almost impossible to obtain information about properties in Turkey, unless you are the owner or an interested party yourself. The land registry office is closed to the public, even for research purposes. The land records are very chaotic and ownership is assigned very differently than in the Western norms. These cause a lot of problems to religious and charitable institutions owned by the minorities. The minute you ask questions about previous ownerships such as only to learn something as simple as the name of the architect of a historical building, people get uncomfortable. Property speculation is very prominent and common in Istanbul. It always has been and will be in the future. And while developers continue with their construction endeavours, if we do not try to preserve the past, it will be lost forever. I cannot believe what is taking place in Tarlabaşı right now. One reads about these things in history books but to witness such drastic changes in one’s lifetime is mind-blowing in the negative sense of the word.

6- How relevant do you think your work is to the present Levantine community in Istanbul?

It is very relevant, because if it was not for the coincidental discovery of records like mine, we would know nothing about these buildings or their owners. As a researcher I cannot look up these records from official channels, but with what we have discovered they can. They still often carry the same surnames and they are the descendants of these people. It thus makes them historically an interested party enabling them to search for these properties. Nothing might come out of it, however they will discover more about their history. They have been through such trauma and are afraid to pursue these things. I cannot blame them. It is better to let the sleeping dogs lie in peace, least they invoke more trouble for their children. We researchers can help them, supply them with more information about their family history. But we only look at the documents. It is their history, their past lives, their great-grandfathers. This history belongs to them and not to us. They are not museum pieces but rather the real residents of Istanbul still living in this ever-changing city.

7- What is the most exciting thing you found in your collection of documents?

I can say almost every document I read is very exciting. You can write papers on each document I have discovered. Each one has an interesting story if you can put all the pieces together.

8- In the ideal world, what would be the best approach of both Levantines and authorities in helping to find the history, ownership and heritage issues of these old buildings you have dealt with?

The authorities should not be afraid to share the information they have. They should stop feeling threatened by Levantines. The Turkish government and state is powerful and the recognition and respect for the previous residents of Istanbul is long overdue. They should do whatever they can to make life easier for the remaining Levantines before it is too late and we lose the young generation as they move abroad. On the other hand Levantines should unite and defend their cause. They must make their voices heard. They should demand the state recognise and fund the history of this community. Walking tours teaching young generations about the previous history of neighbourhoods such as Beyoğlu, Kurtuluş, Yeşilköy, Bakırköy and Adalar must be organized and sponsored by municipalities leaving the state ideologies outside. If your intentions are sincere, marvellous things can be accomplished even with a limited budget. That is why I fully support and work voluntarily for the LHF.

Interview conducted by Craig Encer, November 2015.