Osmanlı’nın Avrupalı Müzisyenleri [European Musicians in the Ottoman Empire] - Evren Kutlay Baydar, Kapı Yayınları, 2010 |

|

Assist. Prof. Dr. Evren KUTLAY (Yıldız Technical University) published a book about European Musicians of Ottoman in 2010. Below are the Foreword and Introduction sections of the book in English and she also explains for us the method of data collection that she used to write her book.

FOREWORD

Tutoress: An erudite European tutoress with perfect mastery of English, French, the piano and notation is willing to instruct Muslim families. Aspirants are asked to apply to the Grand Metropolitan Hotel in Dogruyol, Beyoglu, and ask for “the European tutoress” (the journal Ikdam, 18 August 1894).

After holding to its traditional homophonic musical style for centuries, the Turkish society underwent an innovation in its musical understanding with a process of Westernization, which was first introduced during the reign of Selim III and was actually initiated in 1826 through the reforms of Sultan Mahmud II (1808–1839). Starting with the abolition of the Janissary corps, an event also known in history as Vaka-yi Hayriye (the Auspicious Incident), this reform movement involved reforms to be implemented in music, as well as in all aspects of military and social life. Since military music had a predominant role in performance and production, it was the first area in Turkey to be introduced to polyphonic music, which is still instructed, produced and performed at the present day; and in time, other education institutions also adopted this new style.

After this start, the Westernization movement in music was continued during the reign of Sultan Abdulmejid (1839–1861), the son of Sultan Mahmud II, who succeeded him after his death, and followed his innovations by opening up new institutions for music education, by forming orchestras of both men and women, bands, and by inviting world-wide famous musicians to Istanbul to give concerts, such as Leopold de Meyer and Franz Liszt. Although the flourishing of Western music came to a stop and even slightly declined when Sultan Abdulaziz, who adhered to old traditions and the East in general, acceded to the throne in 1861. There was rekindled interest and accelerated progress in Western music during the reigns of Sultan Murad V, who composed the largest collection of works in Western music forms and reigned for only three months, the shortest in the Ottoman history, in 1876; and of Sultan Abdulhamid II, who succeeded him in 1876 and showed great interest and affinity toward Western music.

Foundations for the current state of Western music in Turkey were laid in the 19th century, which mark the beginning of a process that continued until the performance and production of polyphonic music became a state policy in Turkey under the auspices of Ataturk.

One can gain insight into how Western music was treated and progressed in the Ottoman Era by investigating the musicians, who performed, composed, and taught Western Music in Ottoman lands in that period. The identities, works, and the contributions of those musicians to the Ottoman musical life and history are highly valuable to understand the steps taken in the Republican days, and even in interpreting the point the Turks came today in the field of Western music.

The “European” musicians, who were influential in the progress of Western music during Ottoman Era, worked on Turkish lands for years and left their permanent mark. There were also some Ottoman citizens of Turkish or of European origin, who studied music in Europe, some by the support of scholarships given by the Ottoman Sultans, and turned back after their studies to serve the Empire and later the Republican Turkey. My emphasis on the term “European” stems from the fact that the book deals not only with the musicians, who were born and educated in Europe and then settled in Ottoman lands, or not only with the children of Ottoman families of European origin, who settled in the Empire or were born there; but also with Ottoman musicians of Turkish origin, who, after completing their studies in Europe, came back to their home country and worked in the field of Western music.

In Turkey, so far, some studies on “Western Music in the Ottoman Empire” were done about a selected group of musicians, who returned to the Ottoman lands following their studies in Europe. However, most of these were repetitious works, whose accuracy and adequacy remained unsubstantiated, and which were often based on citations from the publications one of the first and most productive Turkish musicologists Mahmut Ragip Gazimihal. Still, some musicians have never been researched in detail; even the identity of some still remains unknown. Those facts once more demonstrate the need for further studies to fill the gap in the field. I was also tempted by such self-repetitive, undistinguished works and the inconsistencies and shortcomings I noticed in the books about “Western Music in the Ottoman Empire”, a subject which greatly intrigues me. When I began to pursuit my research, I used the resources of national venues such as the Library of Rare Books of Istanbul University (IUNEK), the Turkish public libraries, personal archives of some of the generous Turkish collectors, Turkish Prime Ministerial Ottoman Archives, as well as international resources such as foreign publications, newspapers, and catalogues of libraries abroad. There I recognized that the “European” musicians, who contributed to the progress of Western Music in the Ottoman Empire were not limited to the widely-known commanders of the Imperial Orchestra (Muzika-i Hümâyûn), whose names are repeated in almost any publication about the subject. Although at first glance, the progress in the field of Western Music appears to have taken place mainly in the Ottoman Court, these “other Europeans” in fact effectively integrated themselves into regular public by giving public concerts and by teaching students. Thus, if one is to appreciate who laid the foundations for this musical genre in Turkey and how it was done, it is crucial to shed their identities into light and to investigate what kind of works they produced to establish this music genre during the Ottoman Period. Furthermore, this type of a research will provide valuable insight into the 19th century Ottoman social and cultural life.

In this book, I will present a selection of Western musicians of the Ottomans. One can recognize the names of dozens of musicians, who resided in the Ottoman lands and engaged in musical activities between 1868 and 1923 in a part titled “Professeurs de Musique – Music Instructors” in the Oriental Yearbooks of Commerce (Annuaire Orientale de Commerce), the most valuable reference to identify the name, address and profession of a musician, who lived and worked in Ottoman Era; though this resource has never been noticed and used in a work by any researcher of Turkish music history yet. To study each of these names would mean to write a voluminous encyclopedic collection. Therefore, I selected the names of some musicians from that list in order to provide a preliminary example for such a research in the field. My selection criteria was to include particularly the musicians, whose names appear with incorrect and incomplete information about their biographical data, their artistic contributions, and their musical career in Turkish reference books on “Western Music in the Ottoman Empire” due to the lack of rigorous research. I, hereby, aim to open up a window to both interested readers and researchers, who would be intrigued with the subject of “Western Music in the Ottoman Empire”.

As I looked up for the names and works of the musicians I included in my book in the libraries in Europe and in the continent of America, I was able to identify many facts about them and their works that have neither been discovered till now or nor cited. Even though certain works are located in several libraries, I preferred to name each of them separately by considering researchers, who would like to access to different locations.

To find a sponsor for a music research in Turkey is unfortunately almost impossible, unless a researcher has his/her own personal contacts/relationships. Given that most of the Turkish Universities do not offer any music programs, one could presume the difficult conditions of doing research in this subject. I should mention that I had to conduct my research entirely through my own limited means. The value currently attached to any branch of music is incomparably less than that of the period in question, as is well known by the researchers of Ottoman history. By contributing to the research in this field, I believe we will promote this value that has now lost its past glory, although Ataturk continued to give the highest value to the arts as a continuation of a similar idea that prevailed during the Ottoman Era, and highlighted the huge significance of art by saying “Anyone can be a president or a prime minister, but not everyone can be an artist”.

I would like to extend my thanks to all those, who gave me their very valuable countenance during my research, including Prof. Koral Çalgan, Prof. Ömer Eğecioglu, Renin Kosal, the mother of our treasured pianist late Vedat Kosal, our treasured pianist İdil Biret and her husband Sefik Büyükyüksel, Mert Sandalcı, Dario Lo Cicero from the library of V. Bellini Conservatory in Palermo, Italy, Erwin Strauhal from Vienna Academy of Music, Agnes Watzatka from the library of Liszt Academy of Music in Budapest, Zsuzsa Domokos from Liszt Museum, Luis Miguel Selvelli, the grandson of the Selvelli family, Ufuk Çakmak, İçten Erkin, and the employees of the Ottoman Bank Archives, the Library of Rare Books of Istanbul University, Ataturk Library, Beyazit Public Library, and Prime Ministerial Ottoman Archives. I also deeply appreciate the kind interest and moral support of my piano instructor Zeynep Yurdakul.

INTRODUCTION

Conversation

How much we like music

(…) As for the European [alla franca] music, without doubt, the melodies performed on the piano at homes are nothing less than the most vulgar polkas and quadrilles, and most of our pianophiles are instructed only enough to play the French and Italian operas and operettas and some very simple melodies; and it is hardly possible to find, if any, music lovers who are able to play technically difficult pieces composed by the masters such as Chopin, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Rubinstein and Liszt.

Therefore, one would have to admit that the current state of European music instruction among our families is still in its infancy … (Journal Ikbal, 3 Tesrin-i Sani (November) 1884).

Music in the Ottoman Empire was based on a centuries-old tradition and had its own specific rules. Music occupied an important place both in the Court and military circles, as well as in different classes of the society. In addition to its peculiar theoretical and melodic structure distinguished from the Western system, Turkish music was also transferred from one generation to another orally, in other words, without the use of a notation system for centuries. This transmission system was named formally as “the meşk system”.

The Ottomans encountered with the Western music much earlier than the 19th century. In the 16th century, François I, the King of France, sent Sultan Suleiman, the Magnificent a group of musicians to thank him for his support. Sultan Suleiman accepted this gift and let them to perform. But after listening them to perform, he hastily sent them back to their country, as he feared that this music with “soul-pleasing” qualities would disturb the strict discipline of his own armies.

Again in the 16th century, musical instruments were sent as presents from the West to the Ottoman court. In 1599, upon the order of Queen of England, Elisabeth I, an English organ-maker named Thomas Dallam brought an organ he made himself to Constantinople, re-assembled it in the Topkapı Palace, and played it in front of Sultan Mehmet III. An official correspondence dated 31 January 1599 discovered in the archives of Elizabeth I refers to this organ:1 “Here is a great and curious present going to the Great Turk which no doubt will be much talked of, and be very scandalous among other nations specially the Germans.”

In the 18th century the reigning Sultans were able to get an idea about Western music through the travels of Ottoman ambassadors to Europe. Among them, Yirmisekiz Mehmet Çelebi, who served as the ambassador of France during the reign of Sultan Ahmed III, wrote the following in his memoirs about an opera he watched in Paris:2

“I learned that there is an entertainment peculiar to the city of Paris, which they call opera. It is peculiar for the city. The city’s notables attend, the Regent also often goes there, and even the King occasionally visits the place (...) A Minister, a prestigious person from the nobility, oversees the opera. Although it is an art with heavy costs, they even thought of its financing, and allocated huge sums from the state property. It yields very high revenues and is one of the peculiarities of the city (...). In brief, they showed us too curious things to describe. They showed us thunders and lightings. We saw curiosities and oddities that are impossible to believe unless seen”.

This brief acquaintance with Western music fell short of ensuring its introduction to the Ottoman Court in a real sense, toward which the main steps were taken with the launching of a full-scale Westernization movement during the second half of the 19th century; namely the promulgation of the Tanzimat (Reorganization).

Music in the Ottoman military and Court mainly originated from the janissary band. Toward the 19th century, the janissary corps had turned into an undisciplined, insubordinate, and rebellious military group, which even lost its fighting skills, while European countries were busy with reforming their armies. It was when the reigning Ottoman Sultan Selim III initiated a reform movement and decided to abolish the janissary corps under movement called Nizam-i Cedid (New Order) he promulgated. In this movement starting in 1794, French military officers came to train the Ottoman military modeled on European armies, and they established a bugle band to accompany the newly founded army. However, the efforts of Sultan Selim III as a reformist Sultan failed and the musical reformation movement ground to halt, resulting in the Sultan’s murder in a rebellion. He was briefly succeeded by Sultan Mustafa IV, but his reign brought about a decline in the process. Succeeding Sultan Mustafa IV, Sultan Mahmud II was a reformist Sultan like Sultan Selim III and with him, the Ottoman Empire underwent a real westernization process.

Sultan Mahmud II soon abolished the Janissary corps by an incident called Vaka-ı Hayriye in 16 June 1826, which made its mark on the period. The military bands were not disbanded for a while and the janissary band was left intact. Sultan Mahmud II launched a westernization drive in the entire military, court, and social life. In this context, the army was first reorganized under the name the Victorious Soldiers of Islam (Asakir-i Mansure-i Muhammediye) and was recreated by following the example of its European counterparts under the supervision of European military advisers in all respects from their uniforms to their organization. Yet, the European parade style of this new army turned out to be inharmonious with the pace of the janissary band and its music, upon which the Imperial Janissary Band School (Mehterhane-i Hümâyûn) was closed down in 1827 and to replace it, the Imperial Military Band - Muzıka-ı Hümâyûn was established as an institution to train new bandsmen and to form a new military band that can keep pace with the European styled army3. Thus, the first step in musical reform took place in Ottoman Military music. Although the Imperial Military Band Muzika-i Hümâyûn was originally created for military music (band) training, its content was expanded in the upcoming years to become the first Court Conservatory and would include musical subgroups such as the Court Orchestra, the opera-operetta group, the Turkish music group and the chorus.

The first instructors of Muzıka-ı Hümâyûn, the hussar trumpeter Vaybelim Ahmet Agha and the military drummer Ahmet Usta, were introduced to polyphonic music, albeit in a limited sense, through the activities performed under the supervision of French officers in the bugle team of the military organization called Nizam-ı Cedid (New Order) founded by Selim III in 1794. However, they were sent to other places after a while; so Monsieur Manguel, a Frenchman living in Constantinople, replaced them as the band’s instructor, and later he was dismissed in 1828 on the ground that he was incompetent for the job.4

Following the failure in the training of the new band, Hüsrev Pasha took orders from Sultan Mahmud II to meet the Sardinian ambassador in Constantinople, and asked him to find a competent musician to train the Imperial Band. In those years, Western music and particularly military band system was highly advanced and sophisticated especially in Italy. Thus, Sultan Mahmud II believed that the band could be well trained by an instructor from Italy. For this position, the Sardinian government suggested Giuseppe Donizetti, an Italian military bandmaster, who once served in Napoleon’s army and was deemed competent enough to represent Italian musical culture and dignity; and his brother Gaetano Donizetti was a contemporary renowned composer famous for his operas. When the military band musician Giuseppe Donizetti arrived in Constantinople on 17 September 1828, he was directly summoned to the presence of the Sultan, who had been looking forward to receiving him, and he was awarded with the title “Chief Master of the Orchestras of the Ottoman Sultanate”.5

Donizetti managed to train the band within a short time. The new band was now capable enough to accompany the Sultan at military ceremonies. With the Western-style polyphonic works he composed, Donizetti also paved the way for the development of Western music in the Ottoman Empire. Another Italian, Callisto Guatelli, who succeeded Donizetti as the bandmaster, also had valuable contributions to the progress of Western music in Ottoman lands until his death in 1899. Thanks to Donizetti and Guatelli and other similarly precious and valuable European instructors, who were later charged with supervising the Imperial Band, the European musicians settling in Ottoman lands, and their Turkish counterparts sent to Europe for music education, Western music made considerable progress up until the end of the Ottoman Era and proclamation of the Republic. These “European” teachers trained many treasured Turkish musicians, whose names are still remembered.

Musicians, who chose to leave Europe to settle in Ottoman lands upon recognizing the Empire’s attraction with Western music mainly resided in the Levantine quarters within the triangle of Beyoğlu, Galata and Pera in Constantinople as well as in Izmir (Smyrna). Some of these musicians were invited by the Court to settle in Ottoman lands; served in the Imperial Muzıka-ı Hümâyûn ; and tutored courtiers. Others decided to travel to Turkish lands and stay for a while, as they had been influenced by the positive impressions of other Europeans who had come and settled in the Ottoman Empire before them. Many of them did not return to their countries, and lived in Turkey for the rest of their lives well after the proclamation of the Republic.

The development of Western music also owes much to the minorities and Levantines in Constantinople. In fact, the word minority should be used with caution in this context. That is, these people, who lived as the citizens of the Ottoman Empire should perhaps be regarded as the Ottoman citizens forming the majority rather than the minority in the areas of their settlement. Particularly concentrating in the Pera district of Constantinople, these people might be termed as Turks of European origin. In fact, they lived their lives as Ottoman citizens, not as foreigners, a case which also applies to Izmir (Smyrna).

Grande Rue de Pera, the “Istiklal Street” in Beyoğlu district of the modern-day Istanbul, hosted numerous theaters – chiefly French, Italian, Tepebaşı (Petits Champs des Morts) Theatres and the Naum Theatre – and Concert Halls, where Western music concerts, operas and operettas were put on stage. The performances were regularly announced in daily newspapers and critiques were published after the concerts. Although the Pera district seems to have been the focus of Western music activities, it is clear from these news that these “European” musicians performed in many different cities of the Ottoman Empire from Izmir and Salonika to Cairo and Alexandria, and they even went on concert tours in Europe.

Bartolomeo Pisani, a contemporary Ottoman musician of Italian origin, who once served as the master of the Imperial Conservatory Muzıka-ı Hümâyûn, wrote an article for the newspaper La Turquie, in which he sheds light upon the level of Western music in the 19th century Ottoman Empire.6

“(…) A prejudice has long reigned in Europe. Fortunately, this prejudice tends to fade away, but not yet entirely.

The prejudice in question is as follows:

It is believed that the art of music in Constantinople is still in an embryonic state, the Orientals have very little or no artistic intelligence, we (Ottomans) accept everything imported from foreign countries as they are, we value them and admire them above anything, and we cannot distinguish between either the better among the mediocre or mediocre among the bad. This is indeed a serious mistake.

First to speak of our Glorious Sultan (Abdulhamid II), Our Sultan admires music and Oriental music in particular. His Majesty is clever enough to invite and attract to his Imperial Court anyone with a true gift. A famous artist does not pass through the city without being invited to the Imperial Court, where His Majesty listens to him with the attention of an expert and then honors him with his unique generosity and grace.

We have many distinguished concertists, pianists, violinists, cellists, etc. who long ago chose to reside in Constantinople. These famous artists and teachers honor this sublime art, and represent it with great dignity and glory. We also have amateur [dilettante] ladies who could perfectly replace piano virtuosos. There are extraordinarily beautiful voices, young ladies and young people in the high society and among the middle class (here in Pera) who are ardently and enthusiastically studying the art of singing under the guidance of masters and there is no need to mention their names as they are already well-known.

This is a fact evidenced by the spectacular concerts of last winter (the year 1888) performed by all such locals. In considering all parts of the society, one should not hesitate to say that Constantinople can well match any European city in the field of music (…).

B. Pisani”

The above remark by Pisani, one of the musicians introduced in this book, is valuable in many respects and enlightens us toward a better understanding of those days. Obviously, Western music attained a level comparable to Europe thanks to the musicians, ladies, amateurs and young people of different origins, who settled in the Ottoman lands; Pisani highlighted their identities as “Ottoman citizens” by referring to all of them as “us” and to other countries as “foreign countries”.

Apart from European musicians settling in the Ottoman Empire, there are some Turks, who went to Europe to study music either through the financial support of Ottoman Sultans or with their own means. These Ottoman-Turkish musicians turned back to the Empire after completing their studies and contributed to the advancement of Western music in their homeland. The word “European” also includes selected names among the European musicians serving in the Ottoman Empire, musicians coming from families of European origin although they were born in the Ottoman lands, and the Turkish musicians who received music education in Europe and continued their activities in the Empire.

2 Şevket Rado, Yirmisekiz Mehmet Çelebi’nin Fransa Seyahatnamesi, 1970, pp. 51–53

3 Ancan Özasker, Muzıka-ı Hümayün’den Cumhurbaskanligi Senfoni Orkestrasina, Boyut yayinlari. Istanbul, 1997, p. 6

4 Tayyarzade Ahmet Ata, Enderun Tarihi, vol. III, 1876, R.A. Sevengil, Saray Tiyatrosu, p. 4

5 Mahmut Ragıp Gazimihal, Türk Askeri Muzikalari Tarihi, Maarif Basımevi, Istanbul, 1955, p. 42

6 La Turquie newspaper, 10 December 1889

Book Title: European Musicians of Ottomans

Purpose and Method of Data Collection:

This book includes musicians, who are of European origin but came to Ottoman lands and settled and worked there with the westernization movement during the 19th century, and some Ottoman-Turks, who contributed to the development of Western music in Ottoman Era. Examples of the compositions of all those musicians and musical settings that they took part are added as visuals, which were obtained either from rare works collections of libraries or from the archives of generous collectioners. Moreover, through scanning the catalogues of European libraries, the works of these musicians that they composed while living on Ottoman lands were determined and listed. Archival research is also done through Primeministerail Ottoman Archive in Turkey and through newspapers of the Era, such as La Turquie, New York Times, etc. One important finding is a resource that has never been used in a Turkish music history research, even its presence was not known. Through this resource, the historical mistakes and ambiguities made even by European libraries are presented.

The book aims to state the fact that the works in the area of Western music began before the Republican days of Ataturk, actually was initiated and supported by the Ottoman Sultans and to this end Western musicians were invited and employed, or some came by themselves by hearing the popularity of European music and its appreciation in the Ottoman Empire; and not only the Ottoman citizens of European origin but also Ottoman-Turks were sent to Europe to study music and their studies were supported and their works were awarded by the Ottoman Sultans.

The musicians that are included in this book are the ones that were either never mentioned or handled at a superficial level in studies in the field of Western Music in Ottoman Era. Therefore, this publication also aims to fill this gap in Turkish music history researches, considering the gap in both the historical and musicological studies.

Table of Contents and Chapter Outline:

Chapter I: Italian Musicians of Ottomans

1. The Two Italians of the Ottoman Court: Giuseppe Donizetti and Callisto Guatelli

2. Pisani Family

a. Bartolomeo Pisani (1811-1893)

b. Marline, Honorine, Ed., Ch., Fred., and Pech Pisani

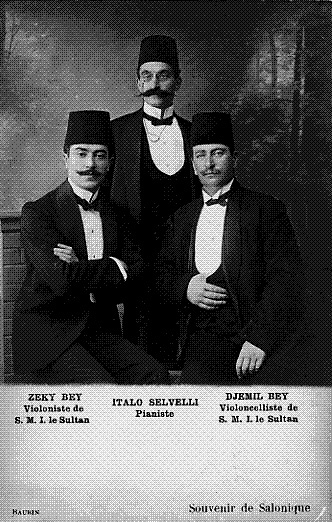

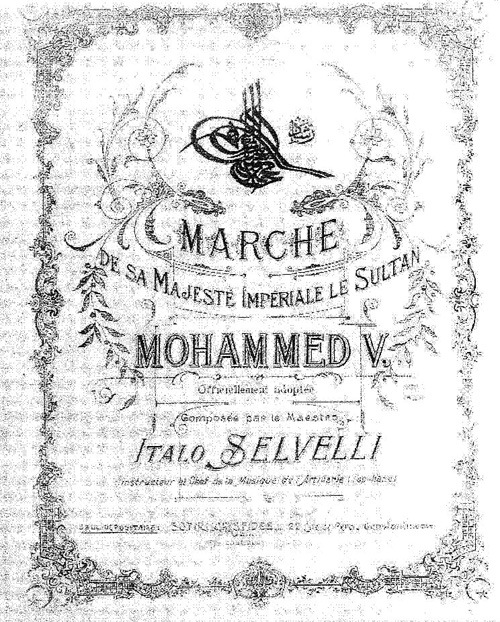

3. Selvelli Family

a. Italo Selvelli (1863-1918)

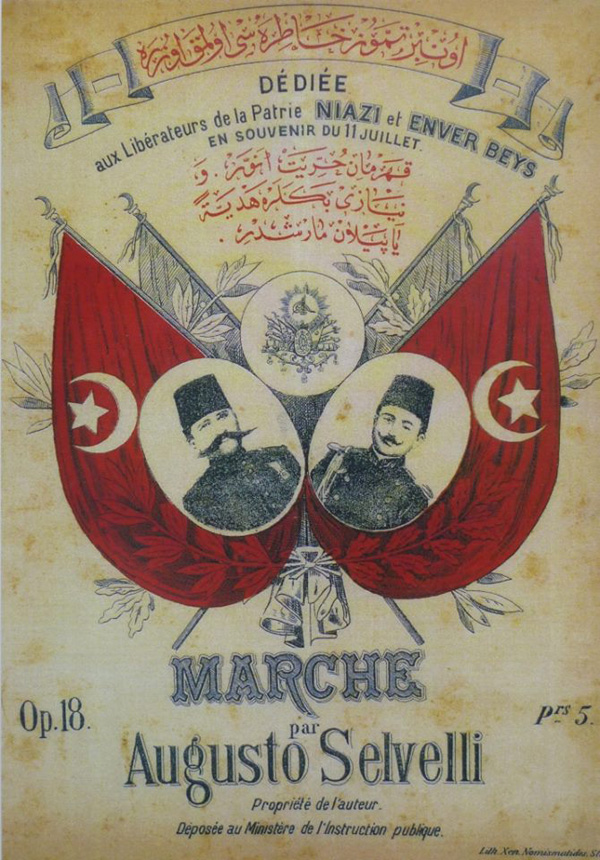

b. Augusto (Guisto) Selvelli (1866-1943)

c. Jules Selvelli

4. Lombardi Family

a. Augusto Lombardi (1844-1913)

b. François Lombardi (1865-1904)

c. Joseph C. Lombardi

5. Giuseppe (Joseph) Parisi (1814-1885)

Chapter II: Following Franz Liszt

1. Ottoman-Hungarian Relationship

2. Liszt School in Ottoman Empire

3. Alessandro Voltan (Hungarian Tevfik) (1853 (?)-1941)

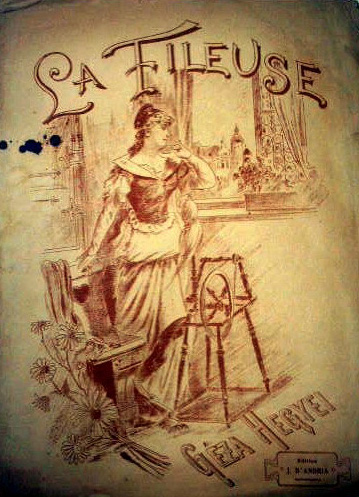

4. Géza Hegyei (1863-1926)

a. Hegyei’s Music Studies with Liszt and afterwards

b. Days in Istanbul at the Ottoman Court

c. Istanbul Concerts and afterwards

5. Karl Berger (1894-1947)

a. Karl Berger’s Violin lessons and concerts

b. Karl Berger and Aliye Berger

Chapter III: An English Musician of Pera District

1. Paul Cervati (1815 (?)- 1897)

Chapter IV: A German Family in the Ottoman Empire: Paul Lange and Hans Lange

1. Paul Lange (1865-1920)

2. Hans Lange (1884-1960)

Chapter V: French School in European Music of Ottomans

1. Fernando de Aranda (1846-1919)

2. Paul Dussap (1840-1922)

3. Enrico Henri Furlani (1870-1940)

Chapter VI: Ottoman-Turk Representatives of European Music

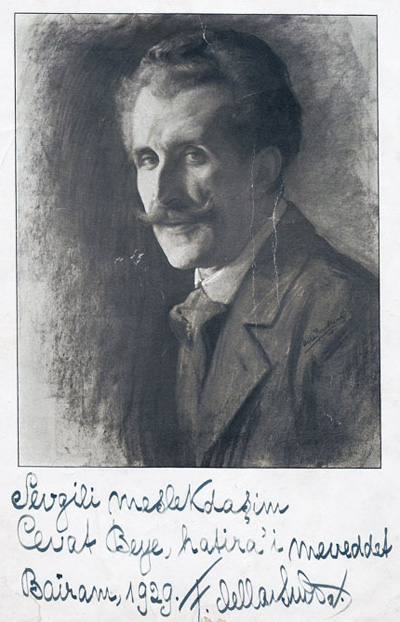

1. Francesco (Faik) Della Sudda Bei

2. Henri Charles Wondra (Wondra Bei) (1868-1905 (?))

3. Students that are sent to Vienna by Ottomans to study music

a. Devlett Effendy (Cosmi Devlett) (1852-1898)

b. Sezai (1898-(?)) and Seifeddin (Asal) Brothers and other Ottoman- Turk students of Vienna Music Academy.

4. Western Side of Eastern Women: Ottoman Women and Their Western Music Studies

a. Western Music Studies of Women in the Court

b. Western Music Studies of Women out of the Court

Epilogue

Bibliography

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Biography: Assist. Prof. Dr. Evren KUTLAY

Dr. Evren Kutlay graduated from German teaching Cagaloglu Anatolian High school and from Boğaziçi University Mathematics Department while studying at Istanbul University State Conservatory Piano Department. Afterwards, she was invited to study with full-scholarship at University of West Georgia, where she received her MBA and her MM in Piano Performance degrees with high honours and worked as a GRA both in Business and Music departments as well as for the University President’s Business class offered to honors students. During her studies in US, she was awarded the “Beta Gamma Sigma International Business Scholars Award” for her successful Business studies. In 2001, she received “Award of Excellence” at GMTA (Georgia Music Teachers Association) piano competition, and in 2002, “Star of the Year” award from MTNA (Music Teachers National Association) as the only foreigner and was invited to become a member of MTNA. During her studies and afterwards, she performed solo, four hand piano music as well as chamber music in Turkey at venues such as Istanbul University, Boğaziçi University, Koç University, Kocaeli University, Istanbul and Ankara Austrian Consulate Cultural Office, Turkish-American Universities Society, Kadıköy Public Education Center, and at Afyon International Classical Music Festival, and in US. She was invited to Conferences in US to present papers as well as to be a jury member at the WPPC International Piano Competition. She completed her Ph.D. in Musicology at Istanbul University Social Sciences Institute. She tought at Koç University for 10 years, where she also worked as the Art Director of Sevgi Gönül Auditorium, which is the Performing Arts Center of Koç University. Right now, she teaches at Yıldız Technical University Music Department as Assist. Professor of Music/Musicology.

In addition to her regular solo and chamber music concerts, she continues her research activities in the area of “Turkish-European musical interaction throughout centuries” focusing on “Western Music during Ottoman Era”. Some of the articles she published in nationally and internationally judged academic journals are titled as “Western Side of Eastern Woman: 19. Century Ottoman Woman and European Music”, “Vive La Liberte! Musical Celebration of II. Constitution”, “Two Italian Musicians at Ottoman Courts: G. Donizetti and C. Guatelli”, and “European Musicians who performed at Ottoman Courts and their Contribution to the Development of Western Music in Ottoman Empire”. She gave seminar series at Suna and Inan Kirac Foundation Istanbul Research Institute and lecture-recital series, in which she performed the repertoire of the period on piano, at Istanbul Technical University MIAM (Music Advanced Research Center) under the main title of “Western Music Adventure of Ottomans”. Moreover, she gave lecture-recitals under the theme of “European Music from the Composer Sultans of Ottomans” and “European Music in 19. Century Istanbul” at national and international venues.

Dr. Evren Kutlay continues her research and concerts in the same area. She has a book titled “Osmanlının Avrupalı Müzisyenleri” (European Musicians of the Ottomans) published by Kapı yayınları in 2010 and a CD recording titled “Dersaadette Avrupa Müziği” (European Music in Ottoman Istanbul) released in 2011 by Anatolian Productions.

|

Wish list: Any contact info, music, pictures or documents of Levantines whose family member, relative or friend was active in the musical life of the Ottomans will be highly appreciated by Professor Kutlay as she keeps researching, lecturing and publishing nationally and internationally about the music life and musicians during the Ottoman Era. Dr. Kutlay can be reached at evrenkutlay[at]gmail.com or through Yıldız Technical University Music Department.