CONTENTS

FOREWORD BY THE EDITOR

PREFACE

I. THE DRAGOMANS

II. BEGINNINGS

III. TURKEY, 1899-1908

IV. TURKEY, 1908-1912

V. TURKEY, 1912-1914

VI. INTERLUDE, 1915-1918

VII. CONSTANTINOPLE, 1918-1921

VIII. CONSTANTINOPLE, 1921-1922

IX. THE LAUSANNE CONFERENCE, 1922-1923

X. AFTER LAUSANNE, 1923-1924

XI. MOROCCO, 1924-1930

XII. ARABIA, 1930-1932

XIII. SAUDI ARABIA, 1932-1936

XIV. ALBANIA, 1936-1939

EPILOGUE

INDEX

Biographical history: Sir Andrew Ryan (1876-1949)

Born 5 November 1876. Educated Christian Brothers College, Cork; Queen’s College, Cork; Emmanuel College, Cambridge. Entered Levant Consular Service, 1897; Vice-Consul at Constantinople, 1903; 2nd Dragoman, Constantinople, 1907; acted as 1st Dragoman, June 1911-July 1912 and March 1914-15; Contraband Office, 1915-18; CMG 1916; 2nd Political Officer on Staff of British High Commissioner, Constantinople; Chief Dragoman, 1921, with rank of Counsellor; member of British Delegation, Near East Peace Conference, Lausanne, 1922-23; Consul General, Rabat, Morocco, 1924-30; KBE 1925; Minister at Jedda, 1930-36; in Albania, 1936-39. Died 31 December 1949.

FOREWORD BY THE EDITOR Sir Reader Bullard

When Sir Andrew Ryan died, on December 31st, 1949, he left his memoirs complete except for the decision what should be omitted if they were to be published. The editing, which was entrusted by his family to an old friend who had worked under him and had twice followed him in independent posts, has consisted mainly in deciding what portions to omit. To leave out everything personal would be to falsify the author's purpose. He declared the book, in the preface, to be an autobiography; and although it is a valuable record of many important public events, it is not a complete history of those events, but mainly a picture of such facets of the time as came under his notice. The personal details which some might reject as trivialities serve as a reminder of the individual nature of the record, while to the discerning reader they show that in spite of the devotion with which Ryan threw himself into his official work, he lived an intensely personal life in which his religion and his family were the chief elements.

With most men of Ryan’s ability, the climax of the career comes at the end. Not so with Ryan. He was always ready to admit that when a consular official became a consul-general he had been paid the highest wages stipulated in the contract, and that any diplomatic post he secured, however humble, was a bonus. Nevertheless, it must have been a disappointment to be offered as his last post the Legation in Albania, which was less difficult to run than many a busy consulate such as fell to men of half his age and a quarter of his experience. It must have been the more disappointing in that it was just not that return to European diplomacy that he hoped for after six years in the unfamiliar world of Arabia. In spite of the zeal with which he discharged his duties as the first British Minister to Saudi Arabia, and the accustomed skill he showed when there were age-old questions to be clarified or agreements to be drafted, he never felt quite at home in Jedda. The un-familiarity of the language and civilization of Arabia, the remoteness of Ibn Saud, who was the real power in the land, and other factors, combined to make him feel at times that Jedda was not quite his job, just as he laughed at himself, the unathletic office-wallah, when called upon to accomplish, as a mere package in a car, the trans-Arabian journey which formerly demanded the highest qualities from the most enterprising and hardy of explorers.

It is to the first thirty years of his official life that one must turn to see Ryan at his best. He can be seen in a typically successful role when it was left to him to tie up the many loose ends left by the Lausanne Conference. He records that his memorandum covered forty-seven points and over a hundred printed pages. It can be said with confidence that any historian who wanted to study those points would be wasting his time if he went beyond this memorandum. Where Ryan has harvested, any gleaner is likely to come home with an empty sack. Ryan had acquired this technique by long practice in Constantinople. As was natural in a country where most questions were affected by the Capitulations, far-reaching but vague and usually in dispute, by constant discussion between the Powers as to their relations with the Porte, and by that procrastination which constituted the Turks' main weapon of defence against the West, the British Embassy had to deal with many questions winding back for years, even decades, over a course rendered even more devious by the incredibly complicated archive system which had been inherited from a less busy past. All these questions Ryan tackled one by one, in spite of the urgent claims of his daily work. He got to the bottom of each, disinterring important facts and invaluable precedents, and left the gist of it easily accessible to his fortunate colleagues and successors. In the course of his researches and in his daily contact with Turkish officials and foreign diplomats, he acquired an unrivalled knowledge of matters affecting British interests in Turkey, and this knowledge he wielded with an acute brain which was belied by the slowness of his speech. Anyone who made a careless statement in an argument with Ryan was liable to be crushed immediately by a Johnsonian example which would prove that the proposition was not universally, if ever, valid. These qualities, combined with firm principles which, nevertheless, contained no element of fanaticism, made him a most formidable member of the British Mission at the Lausanne Conference, and an invaluable adviser to his chiefs in Constantinople for many years. His five years in French Morocco were equally happy and successful. There he lived in a familiar atmosphere: he was dealing with European diplomats in a language he knew well and whose official phraseology he could almost write in his sleep; he still had Capitulations to deal with, though with changes important enough to arouse his interest and occupy his inquiring mind; and the newness of the post raised a host of problems for him to settle as precedents for others. The regard he won from the French officials was a measure of his success; it had as counterpart the respect and affection of the British colleagues who worked under his supervision and who constituted with him as happy an official family as one could wish to find.

The compiler of monumental memoranda is not, as a rule, gay company, but Ryan, in spite of a reserve which had its roots in modesty, could be extremely entertaining. His topical verse lightened many a dark hour, and if few specimens of it are printed here, that is because such verse needs to be read hot on the heels of the events that have provoked it, preferably by those who have lived through the events and catch the lightest allusion. He could produce delightful epigrams for his friends, for a wedding or a birthday or other great occasion; some of them are preserved, at least orally, to this day. Some of his spoken jests, the more penetrating for being uttered so slowly, attained a wide circulation. At the time of the first, abortive, Lausanne Conference, when Lord Curzon was wrestling with Ismet Pasha under the impassive gaze of Mr. Childs, the American observer, he uttered a mot on which a Permanent Under-Secretary (not in the Foreign Office) claimed to have dined out for a week: "I hope it will not be said that Lord Curzon came, Mr. Childs saw, and Ismet Pasha conquered.'' Most of his jests contained a core of wisdom — that aphorism, for example, uttered when two rather light-minded young people announced their engagement, that "a balloon should marry a rock." He did not uphold the converse of this aphorism, and he himself married another rock, to his own great happiness and the no small advantage of his friends and colleagues.

It is possible to be a competent official without being an admirable human being, but Ryan's work was more than competent, being illumined by the qualities of his character —the patience and sympathy, the integrity and magnanimity, that he brought to everything he did. Cruelty, dishonesty or culpable slackness could arouse his anger, but he was the kindest and most generous of men. The heroic pose may wilt before the valet's eye, and many a high official with a great reputation seems small enough to his subordinates. Ryan, however, could survive that severe test; apart from the respect which they felt for him and his work, those who served under him found that his personal kindness and hospitality were outrun, if that were possible, by the help and support he gave them in their work. In his relations with them, as with everyone else, he was animated by his religion—a fact evident not only to his co-religionists but also to friends of other Churches or of no church at all. He lived consciously in his great Taskmaster’s eye; and when he knew that he might die very soon he said, no less truly than simply, “Well, I have been preparing for this all my life.”

November 1950 R. W. B.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

PREFACE by Sir Andrew Ryan

This book is primarily an autobiography. My excuse for publishing a record so personal must be that for forty years I played small parts on considerable stages. The events which developed on those stages have been surpassed in importance, and above all in horror, by those of the last ten years. Nevertheless, those which I witnessed, especially in Turkey and Arabia, were significant preludes to the present situation in the Near and Middle East. Even the trivialities may help to illustrate the setting of a dead past.

I have been at pains to ensure historical accuracy. Most of the book, however, has been written in a country village, remote from libraries and official sources of information. If I have gone wrong on points of fact, I apologize in advance to the professional historian.

I have not considered it necessary, in a book like this, to attempt any strict consistency in the rendering of Turkish and Arabic names. The difficulty of reproducing satisfactorily in European characters words—especially Arabic words—written in the Arabic script formerly used in Turkey is familiar to all writers and readers of works in which they occur. Scientific systems of transliteration, though valuable for purposes of pure scholarship, produce results repugnant to the eye and often positively misleading to the ear.

I am indebted to my wife and my sister for ploughing through my manuscript and making several suggestions; and to Miss Joan Shipston for reducing it to legible form, undaunted by my notorious handwriting. I cannot attempt to name individually the many former colleagues and friends to whom I have reason to be grateful. Their letters, old and new, have served to refresh my memory, and not a few have helped me in various other ways. Piety demands an exception in the case of Sir A. Telford Waugh who was my first immediate chief in the Consular Service, and who has crowned half a century of friendship by interesting himself in what I have written. I trust that I have not poached unduly on his preserves by covering some of the same ground as he himself did in the valuable reminiscences which he published on his retirement twenty years ago, under the title “Turkey Yesterday, To-Day and To-Morrow”.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

CHAPTER I

THE DRAGOMANS

The word “dragoman” is one of the many European corruptions of the Arabic word for translator or interpreter. In old days in Turkey it applied equally to the modest guides who helped travellers and to persons employed by the foreign diplomatic missions and consulates in the conduct of their business with the Turkish authorities. These, if primarily needed for their linguistic qualifications, were, in fact, much more than interpreters. They were honest or, as their enemies averred, dishonest brokers between the foreign representatives and the Turks for a great variety of purposes. The system was inextricably bound up with the operation of the Capitulations, or “ancient treaties” as the Turks called them, although the earliest were in the form of grants by the Sultans. These instruments, and subsequent agreements of a more normal type, conferred on practically all foreigners a privileged status, notably as regards jurisdiction and taxation, throughout the Ottoman Empire. In earlier times the dragomans were in some sense the common property of the Embassies and the Porte. They were normally drawn from the local population and, more especially in Constantinople and the great commercial centres, from among the Levantines of mixed origin who abounded therein. Attempts were made from time to time to raise the standard. The French system of training likely lads, jeunes de langues as they were called, to become dragomans eventually was initiated by Colbert as early as 1669, and survived, in spite of many vicissitudes, until late in the nineteenth century. In the eighteenth century it was identified with the Jesuit College of Louis le Grand, and was afterwards extended to other lycees, in which the boys received preliminary instruction with a view to going East to specialize in the local languages. I have an un verified impression that at some time during the nineteenth century the British Government tried a similar experiment, but it was not until 1877 that a special service, familiarly known in after years as the Levant Consular Service, was created with the object of recruiting natural-born British subjects by competitive examination to fill the more important consular posts in Turkey, Persia, Greece and Morocco, including the dragomanates of the Embassy and the Consulate in Constantinople. This reform produced little effect in Greece and Morocco, but rather more in Persia; and it had full play in the Ottoman Empire, including Egypt, for the best part of half a century. At first a school was maintained at Ortakeui on the Bosphorus to provide for the special studies of the entrants, but in 1894 it was arranged that they should pursue those studies for two years at Oxford or Cambridge, principally the latter as things worked out, before going to the East.

The dragomans of the old school were still in active service in Constantinople for some little time after I went there in 1899. They were Stavrides, a notable authority on Turkish law, and Marinitsch, a man of some Dalmatian origin, who, after serving the Porte and at least one foreign Legation, settled down to many years of most useful work in the British Embassy. They were the last of a line of men, some of considerable distinction, who abounded in local knowledge, but who, for that very reason, were not as detached from the native setting as was considered desirable by the authors of the reform of 1877. Even that great change, however, did not end the controversies surrounding the principle of relying on dragomans, whatsoever the system of recruitment, for expert advice and the conduct of business with the Turks. They were obviously an excrescence on the machinery of diplomatic intercourse as conceived in Western Europe...

p.27

I landed in Constantinople on Sunday, June 4th [1899]. Going to Consulate, I found that all the staff were off duty and that my school Turkish was unintelligible to the native servants. I spent a disconsolate afternoon wandering among the cemeteries in the northern part of the dull European and Christian quarter. A solitary evening in the old Hotel Bristol was hardly more cheerful, and it was not until next day that I entered on my new life. Returning to the Consulate, I made contact with my first chief, A.T.Waugh, who was acting as Consul, and my future colleagues in the Dragomanate, old Stavrides, the legal oracle mentioned earlier as a survivor from the old regime, and two juniors, Macaulay and Toulmin, who were soon to leave the Service. That was the beginning of a lifelong friendship with Waugh. It was under his auspices that I moved to the more genial surroundings of the Club de Constantinople, and spent the following week-end at Prinkipo with the family of Woods Pasha, one of the Sultan’s admirals. The Club was a friendly place, international but dominated at the time by the British element. It was not so smart or exclusive as the famous Cercle d’Orient, sacred to diplomats, financiers and other considerable personages, but it was better housed and was greatly frequented by Europeans in the second class of what was then a highly compartmented society, consular officers, merchants and men of equivalent standing.

p.48

Constantinople in those early years was a most remarkable place of residence for foreigners. In the absence of a court, the great centres of social life were the embassies and certain legations. Their principal members lived a great deal in a high and rarefied atmosphere of their own, looking down somewhat on lesser breeds, excepting perhaps a privileged few whose wealth or station ensured admittance to the charmed circle. We junior consular officers were very distinctly a lesser breed, men profane to the mysteries of diplomacy and apt to be infected with a disease known in the language of Olympus as Morbus Consularis, or l’esprit capitulaire. This is of course a too sweeping a generalization. Even in those days I had good friends in the Embassy circle, but there was undoubtedly a barrier. On the other hand, the principal foreign colonies had very pleasant lives of their own. Even in these there were well-marked social distinctions, which might seem absurd nowadays. They were largely determined by place of residence, in which families hung much together. The elite of the non-official British community lived mostly in Moda, on the Asiatic shore of the Sea of Marmara, or in Candilli on the middle Bosphorus. All the embassies and many private persons wintered in Pera, and moved to the country for several months in the summer and autumn. I myself up to 1907 usually spent the winter in town and moved to Candilli in May or June. My greatest friends were the family of Eyres, our Consul-General, and, until they went to Shanghai in 1906, a couple in Candilli, de Sausmarez, the Judge to the Consular Court, and his most charming wife. In both houses I enjoyed infinite hospitality.

The Eyres and de Sausmarez houses were only two of many which I remember with gratitude. In Pera and Therapia the house of Woods Pasha and his gracious wife was a centre where all met on the easiest terms. Sir Hamilton and Lady Lang dispensed a large hospitality in the impressive house which he occupied as Director-General of the Ottoman Bank. For several summers we juniors, the Dragoboys as some called us, had a bachelor mess in Candilli, living in yalis (waterside houses) in the old Turkish style. One of these could boast a central hall so large that from front to back it measured the length of a cricket pitch. We saw much of our fairly numerous British neighbours, among them the Whitakers and the Cliftons, one of whom, Dorina Clifton, now lady Neave, has published her own reminiscences. I went constantly to Moda, where I knew the many families of the great Whittall clan and was intimate with others. It was there especially that I formed the favourable opinion which I have always had of the leading representatives of the so-called Levantines. I have never, for instance, known a truer gentleman than Tom Maltass, the head of the family which I frequented most of all in Moda.

Most of the British residents were comfortably off and many of them prosperous. Their great pleasure was to entertain their friends. If we did not move intimately in the inner Embassy circle, we were invited not infrequently to functions there. The greatest annual event in British life was a giant garden party on the Queen’s – later the King’s – birthday. It was all the larger as it was the one occasion in the year on which Turkish officials generally had permission to go into British society.

I was exceptional, and on balance fortunate, in remaining fixed in Constantinople. This was a result of my having specialized in the work of a dragoman and having already had training in it at the Consulate-General, when it became necessary to restaff the Embassy Dragomanate.

CHAPTER V

Turkey, 1912-14

...

During most of this time, however, I was still on leave, and taken up less with public events than with my own private affairs. I had long been a friend of Professor A. van Millingen, of Robert College, Constantinople, a great authority on Byzantine archaeology, and of his much younger Scots wife, a lively and attractive woman. A brother of the professor’s, Julius van Millingen, had left Turkey for Scotland on retirement from service in the Ottoman Bank a year or so after my arrival there, but his daughter Ruth came out sometimes to visit her uncle in Constantinople. Thus it was that I had come to know and admire the granddaughter of that elder Julius van Millingen who, as I have already mentioned, had looked forward so cheerfully to the disappearance of the dragomans. I now became engaged to her, during my leave, and so rounded off in the happiest possible manner several unsuccessful love affairs.

I returned from leave on December 9th, a week before the opening of the peace conference in London. Constantinople seemed normal enough, but it was full of Red Crescent hospitals and there was widespread depression. Kiamal Pasha was still in office. The Committee were very much at a discount. A rival party called the Entente Libérale had come into being a year before, under the auspices of a certain Colonel Sadik, a decent fellow but of no great weight. The London Conference was dragging on, but the climax came in Constantinople. The Turks were under strong and, as it seemed to the Government, irresistible pressure to cede Adrianople.

Note: Ryan’s legacy was not considered positive in Turkey as this extract from a Turkish web-site reveals:

Mr. Andrew Ryan, a Catholic Irishman, was a notorious anti-Turk intriguer and described as the “most hated man” in Turkey. He has served as a Dragoman or interpreter in the British Embassy at Istanbul for fifteen years before the World War, from 1899 to 1914, and had many old contacts with native Armenians, Greeks and Turks in Istanbul. Now he became chief Dragoman to the British High Commission and assumed at the same time the role of Second Political officer. He was charged mainly with the Armenian question.

Mr. Ryan wrote that as soon as he arrived in Istanbul in November 1918, he renewed many old contacts with Europeans, Turks and native Christians and established new ones. Under his responsibility a special Section of the British High Commission was created to deal with the Armenian and Greek “victims of persecution”. He was to play a role in causing the arrest and deportation of many Turkish personalities. “The Chief Dragoman had always been in some sense the alter ego of the Ambassador in relations to the Turks. Mr. Ryan wrote, and it was more than necessary in armistice conditions that there should be someone capable of playing the same role for the admirals (Calthorpe and Webb)... I was as busy as any of my predecessors in maintaining touch with ministers and other Turks, collecting information, following the affairs of the non-moslem minorities and drafting countless telegrams and despatches”.

FOREWORD BY THE EDITOR

PREFACE

I. THE DRAGOMANS

II. BEGINNINGS

III. TURKEY, 1899-1908

IV. TURKEY, 1908-1912

V. TURKEY, 1912-1914

VI. INTERLUDE, 1915-1918

VII. CONSTANTINOPLE, 1918-1921

VIII. CONSTANTINOPLE, 1921-1922

IX. THE LAUSANNE CONFERENCE, 1922-1923

X. AFTER LAUSANNE, 1923-1924

XI. MOROCCO, 1924-1930

XII. ARABIA, 1930-1932

XIII. SAUDI ARABIA, 1932-1936

XIV. ALBANIA, 1936-1939

EPILOGUE

INDEX

Biographical history: Sir Andrew Ryan (1876-1949)

Born 5 November 1876. Educated Christian Brothers College, Cork; Queen’s College, Cork; Emmanuel College, Cambridge. Entered Levant Consular Service, 1897; Vice-Consul at Constantinople, 1903; 2nd Dragoman, Constantinople, 1907; acted as 1st Dragoman, June 1911-July 1912 and March 1914-15; Contraband Office, 1915-18; CMG 1916; 2nd Political Officer on Staff of British High Commissioner, Constantinople; Chief Dragoman, 1921, with rank of Counsellor; member of British Delegation, Near East Peace Conference, Lausanne, 1922-23; Consul General, Rabat, Morocco, 1924-30; KBE 1925; Minister at Jedda, 1930-36; in Albania, 1936-39. Died 31 December 1949.

FOREWORD BY THE EDITOR Sir Reader Bullard

When Sir Andrew Ryan died, on December 31st, 1949, he left his memoirs complete except for the decision what should be omitted if they were to be published. The editing, which was entrusted by his family to an old friend who had worked under him and had twice followed him in independent posts, has consisted mainly in deciding what portions to omit. To leave out everything personal would be to falsify the author's purpose. He declared the book, in the preface, to be an autobiography; and although it is a valuable record of many important public events, it is not a complete history of those events, but mainly a picture of such facets of the time as came under his notice. The personal details which some might reject as trivialities serve as a reminder of the individual nature of the record, while to the discerning reader they show that in spite of the devotion with which Ryan threw himself into his official work, he lived an intensely personal life in which his religion and his family were the chief elements.

With most men of Ryan’s ability, the climax of the career comes at the end. Not so with Ryan. He was always ready to admit that when a consular official became a consul-general he had been paid the highest wages stipulated in the contract, and that any diplomatic post he secured, however humble, was a bonus. Nevertheless, it must have been a disappointment to be offered as his last post the Legation in Albania, which was less difficult to run than many a busy consulate such as fell to men of half his age and a quarter of his experience. It must have been the more disappointing in that it was just not that return to European diplomacy that he hoped for after six years in the unfamiliar world of Arabia. In spite of the zeal with which he discharged his duties as the first British Minister to Saudi Arabia, and the accustomed skill he showed when there were age-old questions to be clarified or agreements to be drafted, he never felt quite at home in Jedda. The un-familiarity of the language and civilization of Arabia, the remoteness of Ibn Saud, who was the real power in the land, and other factors, combined to make him feel at times that Jedda was not quite his job, just as he laughed at himself, the unathletic office-wallah, when called upon to accomplish, as a mere package in a car, the trans-Arabian journey which formerly demanded the highest qualities from the most enterprising and hardy of explorers.

It is to the first thirty years of his official life that one must turn to see Ryan at his best. He can be seen in a typically successful role when it was left to him to tie up the many loose ends left by the Lausanne Conference. He records that his memorandum covered forty-seven points and over a hundred printed pages. It can be said with confidence that any historian who wanted to study those points would be wasting his time if he went beyond this memorandum. Where Ryan has harvested, any gleaner is likely to come home with an empty sack. Ryan had acquired this technique by long practice in Constantinople. As was natural in a country where most questions were affected by the Capitulations, far-reaching but vague and usually in dispute, by constant discussion between the Powers as to their relations with the Porte, and by that procrastination which constituted the Turks' main weapon of defence against the West, the British Embassy had to deal with many questions winding back for years, even decades, over a course rendered even more devious by the incredibly complicated archive system which had been inherited from a less busy past. All these questions Ryan tackled one by one, in spite of the urgent claims of his daily work. He got to the bottom of each, disinterring important facts and invaluable precedents, and left the gist of it easily accessible to his fortunate colleagues and successors. In the course of his researches and in his daily contact with Turkish officials and foreign diplomats, he acquired an unrivalled knowledge of matters affecting British interests in Turkey, and this knowledge he wielded with an acute brain which was belied by the slowness of his speech. Anyone who made a careless statement in an argument with Ryan was liable to be crushed immediately by a Johnsonian example which would prove that the proposition was not universally, if ever, valid. These qualities, combined with firm principles which, nevertheless, contained no element of fanaticism, made him a most formidable member of the British Mission at the Lausanne Conference, and an invaluable adviser to his chiefs in Constantinople for many years. His five years in French Morocco were equally happy and successful. There he lived in a familiar atmosphere: he was dealing with European diplomats in a language he knew well and whose official phraseology he could almost write in his sleep; he still had Capitulations to deal with, though with changes important enough to arouse his interest and occupy his inquiring mind; and the newness of the post raised a host of problems for him to settle as precedents for others. The regard he won from the French officials was a measure of his success; it had as counterpart the respect and affection of the British colleagues who worked under his supervision and who constituted with him as happy an official family as one could wish to find.

The compiler of monumental memoranda is not, as a rule, gay company, but Ryan, in spite of a reserve which had its roots in modesty, could be extremely entertaining. His topical verse lightened many a dark hour, and if few specimens of it are printed here, that is because such verse needs to be read hot on the heels of the events that have provoked it, preferably by those who have lived through the events and catch the lightest allusion. He could produce delightful epigrams for his friends, for a wedding or a birthday or other great occasion; some of them are preserved, at least orally, to this day. Some of his spoken jests, the more penetrating for being uttered so slowly, attained a wide circulation. At the time of the first, abortive, Lausanne Conference, when Lord Curzon was wrestling with Ismet Pasha under the impassive gaze of Mr. Childs, the American observer, he uttered a mot on which a Permanent Under-Secretary (not in the Foreign Office) claimed to have dined out for a week: "I hope it will not be said that Lord Curzon came, Mr. Childs saw, and Ismet Pasha conquered.'' Most of his jests contained a core of wisdom — that aphorism, for example, uttered when two rather light-minded young people announced their engagement, that "a balloon should marry a rock." He did not uphold the converse of this aphorism, and he himself married another rock, to his own great happiness and the no small advantage of his friends and colleagues.

It is possible to be a competent official without being an admirable human being, but Ryan's work was more than competent, being illumined by the qualities of his character —the patience and sympathy, the integrity and magnanimity, that he brought to everything he did. Cruelty, dishonesty or culpable slackness could arouse his anger, but he was the kindest and most generous of men. The heroic pose may wilt before the valet's eye, and many a high official with a great reputation seems small enough to his subordinates. Ryan, however, could survive that severe test; apart from the respect which they felt for him and his work, those who served under him found that his personal kindness and hospitality were outrun, if that were possible, by the help and support he gave them in their work. In his relations with them, as with everyone else, he was animated by his religion—a fact evident not only to his co-religionists but also to friends of other Churches or of no church at all. He lived consciously in his great Taskmaster’s eye; and when he knew that he might die very soon he said, no less truly than simply, “Well, I have been preparing for this all my life.”

November 1950 R. W. B.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

PREFACE by Sir Andrew Ryan

This book is primarily an autobiography. My excuse for publishing a record so personal must be that for forty years I played small parts on considerable stages. The events which developed on those stages have been surpassed in importance, and above all in horror, by those of the last ten years. Nevertheless, those which I witnessed, especially in Turkey and Arabia, were significant preludes to the present situation in the Near and Middle East. Even the trivialities may help to illustrate the setting of a dead past.

I have been at pains to ensure historical accuracy. Most of the book, however, has been written in a country village, remote from libraries and official sources of information. If I have gone wrong on points of fact, I apologize in advance to the professional historian.

I have not considered it necessary, in a book like this, to attempt any strict consistency in the rendering of Turkish and Arabic names. The difficulty of reproducing satisfactorily in European characters words—especially Arabic words—written in the Arabic script formerly used in Turkey is familiar to all writers and readers of works in which they occur. Scientific systems of transliteration, though valuable for purposes of pure scholarship, produce results repugnant to the eye and often positively misleading to the ear.

I am indebted to my wife and my sister for ploughing through my manuscript and making several suggestions; and to Miss Joan Shipston for reducing it to legible form, undaunted by my notorious handwriting. I cannot attempt to name individually the many former colleagues and friends to whom I have reason to be grateful. Their letters, old and new, have served to refresh my memory, and not a few have helped me in various other ways. Piety demands an exception in the case of Sir A. Telford Waugh who was my first immediate chief in the Consular Service, and who has crowned half a century of friendship by interesting himself in what I have written. I trust that I have not poached unduly on his preserves by covering some of the same ground as he himself did in the valuable reminiscences which he published on his retirement twenty years ago, under the title “Turkey Yesterday, To-Day and To-Morrow”.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

CHAPTER I

THE DRAGOMANS

The word “dragoman” is one of the many European corruptions of the Arabic word for translator or interpreter. In old days in Turkey it applied equally to the modest guides who helped travellers and to persons employed by the foreign diplomatic missions and consulates in the conduct of their business with the Turkish authorities. These, if primarily needed for their linguistic qualifications, were, in fact, much more than interpreters. They were honest or, as their enemies averred, dishonest brokers between the foreign representatives and the Turks for a great variety of purposes. The system was inextricably bound up with the operation of the Capitulations, or “ancient treaties” as the Turks called them, although the earliest were in the form of grants by the Sultans. These instruments, and subsequent agreements of a more normal type, conferred on practically all foreigners a privileged status, notably as regards jurisdiction and taxation, throughout the Ottoman Empire. In earlier times the dragomans were in some sense the common property of the Embassies and the Porte. They were normally drawn from the local population and, more especially in Constantinople and the great commercial centres, from among the Levantines of mixed origin who abounded therein. Attempts were made from time to time to raise the standard. The French system of training likely lads, jeunes de langues as they were called, to become dragomans eventually was initiated by Colbert as early as 1669, and survived, in spite of many vicissitudes, until late in the nineteenth century. In the eighteenth century it was identified with the Jesuit College of Louis le Grand, and was afterwards extended to other lycees, in which the boys received preliminary instruction with a view to going East to specialize in the local languages. I have an un verified impression that at some time during the nineteenth century the British Government tried a similar experiment, but it was not until 1877 that a special service, familiarly known in after years as the Levant Consular Service, was created with the object of recruiting natural-born British subjects by competitive examination to fill the more important consular posts in Turkey, Persia, Greece and Morocco, including the dragomanates of the Embassy and the Consulate in Constantinople. This reform produced little effect in Greece and Morocco, but rather more in Persia; and it had full play in the Ottoman Empire, including Egypt, for the best part of half a century. At first a school was maintained at Ortakeui on the Bosphorus to provide for the special studies of the entrants, but in 1894 it was arranged that they should pursue those studies for two years at Oxford or Cambridge, principally the latter as things worked out, before going to the East.

The dragomans of the old school were still in active service in Constantinople for some little time after I went there in 1899. They were Stavrides, a notable authority on Turkish law, and Marinitsch, a man of some Dalmatian origin, who, after serving the Porte and at least one foreign Legation, settled down to many years of most useful work in the British Embassy. They were the last of a line of men, some of considerable distinction, who abounded in local knowledge, but who, for that very reason, were not as detached from the native setting as was considered desirable by the authors of the reform of 1877. Even that great change, however, did not end the controversies surrounding the principle of relying on dragomans, whatsoever the system of recruitment, for expert advice and the conduct of business with the Turks. They were obviously an excrescence on the machinery of diplomatic intercourse as conceived in Western Europe...

p.27

I landed in Constantinople on Sunday, June 4th [1899]. Going to Consulate, I found that all the staff were off duty and that my school Turkish was unintelligible to the native servants. I spent a disconsolate afternoon wandering among the cemeteries in the northern part of the dull European and Christian quarter. A solitary evening in the old Hotel Bristol was hardly more cheerful, and it was not until next day that I entered on my new life. Returning to the Consulate, I made contact with my first chief, A.T.Waugh, who was acting as Consul, and my future colleagues in the Dragomanate, old Stavrides, the legal oracle mentioned earlier as a survivor from the old regime, and two juniors, Macaulay and Toulmin, who were soon to leave the Service. That was the beginning of a lifelong friendship with Waugh. It was under his auspices that I moved to the more genial surroundings of the Club de Constantinople, and spent the following week-end at Prinkipo with the family of Woods Pasha, one of the Sultan’s admirals. The Club was a friendly place, international but dominated at the time by the British element. It was not so smart or exclusive as the famous Cercle d’Orient, sacred to diplomats, financiers and other considerable personages, but it was better housed and was greatly frequented by Europeans in the second class of what was then a highly compartmented society, consular officers, merchants and men of equivalent standing.

p.48

Constantinople in those early years was a most remarkable place of residence for foreigners. In the absence of a court, the great centres of social life were the embassies and certain legations. Their principal members lived a great deal in a high and rarefied atmosphere of their own, looking down somewhat on lesser breeds, excepting perhaps a privileged few whose wealth or station ensured admittance to the charmed circle. We junior consular officers were very distinctly a lesser breed, men profane to the mysteries of diplomacy and apt to be infected with a disease known in the language of Olympus as Morbus Consularis, or l’esprit capitulaire. This is of course a too sweeping a generalization. Even in those days I had good friends in the Embassy circle, but there was undoubtedly a barrier. On the other hand, the principal foreign colonies had very pleasant lives of their own. Even in these there were well-marked social distinctions, which might seem absurd nowadays. They were largely determined by place of residence, in which families hung much together. The elite of the non-official British community lived mostly in Moda, on the Asiatic shore of the Sea of Marmara, or in Candilli on the middle Bosphorus. All the embassies and many private persons wintered in Pera, and moved to the country for several months in the summer and autumn. I myself up to 1907 usually spent the winter in town and moved to Candilli in May or June. My greatest friends were the family of Eyres, our Consul-General, and, until they went to Shanghai in 1906, a couple in Candilli, de Sausmarez, the Judge to the Consular Court, and his most charming wife. In both houses I enjoyed infinite hospitality.

The Eyres and de Sausmarez houses were only two of many which I remember with gratitude. In Pera and Therapia the house of Woods Pasha and his gracious wife was a centre where all met on the easiest terms. Sir Hamilton and Lady Lang dispensed a large hospitality in the impressive house which he occupied as Director-General of the Ottoman Bank. For several summers we juniors, the Dragoboys as some called us, had a bachelor mess in Candilli, living in yalis (waterside houses) in the old Turkish style. One of these could boast a central hall so large that from front to back it measured the length of a cricket pitch. We saw much of our fairly numerous British neighbours, among them the Whitakers and the Cliftons, one of whom, Dorina Clifton, now lady Neave, has published her own reminiscences. I went constantly to Moda, where I knew the many families of the great Whittall clan and was intimate with others. It was there especially that I formed the favourable opinion which I have always had of the leading representatives of the so-called Levantines. I have never, for instance, known a truer gentleman than Tom Maltass, the head of the family which I frequented most of all in Moda.

Most of the British residents were comfortably off and many of them prosperous. Their great pleasure was to entertain their friends. If we did not move intimately in the inner Embassy circle, we were invited not infrequently to functions there. The greatest annual event in British life was a giant garden party on the Queen’s – later the King’s – birthday. It was all the larger as it was the one occasion in the year on which Turkish officials generally had permission to go into British society.

I was exceptional, and on balance fortunate, in remaining fixed in Constantinople. This was a result of my having specialized in the work of a dragoman and having already had training in it at the Consulate-General, when it became necessary to restaff the Embassy Dragomanate.

CHAPTER V

Turkey, 1912-14

...

During most of this time, however, I was still on leave, and taken up less with public events than with my own private affairs. I had long been a friend of Professor A. van Millingen, of Robert College, Constantinople, a great authority on Byzantine archaeology, and of his much younger Scots wife, a lively and attractive woman. A brother of the professor’s, Julius van Millingen, had left Turkey for Scotland on retirement from service in the Ottoman Bank a year or so after my arrival there, but his daughter Ruth came out sometimes to visit her uncle in Constantinople. Thus it was that I had come to know and admire the granddaughter of that elder Julius van Millingen who, as I have already mentioned, had looked forward so cheerfully to the disappearance of the dragomans. I now became engaged to her, during my leave, and so rounded off in the happiest possible manner several unsuccessful love affairs.

I returned from leave on December 9th, a week before the opening of the peace conference in London. Constantinople seemed normal enough, but it was full of Red Crescent hospitals and there was widespread depression. Kiamal Pasha was still in office. The Committee were very much at a discount. A rival party called the Entente Libérale had come into being a year before, under the auspices of a certain Colonel Sadik, a decent fellow but of no great weight. The London Conference was dragging on, but the climax came in Constantinople. The Turks were under strong and, as it seemed to the Government, irresistible pressure to cede Adrianople.

Note: Ryan’s legacy was not considered positive in Turkey as this extract from a Turkish web-site reveals:

Mr. Andrew Ryan, a Catholic Irishman, was a notorious anti-Turk intriguer and described as the “most hated man” in Turkey. He has served as a Dragoman or interpreter in the British Embassy at Istanbul for fifteen years before the World War, from 1899 to 1914, and had many old contacts with native Armenians, Greeks and Turks in Istanbul. Now he became chief Dragoman to the British High Commission and assumed at the same time the role of Second Political officer. He was charged mainly with the Armenian question.

Mr. Ryan wrote that as soon as he arrived in Istanbul in November 1918, he renewed many old contacts with Europeans, Turks and native Christians and established new ones. Under his responsibility a special Section of the British High Commission was created to deal with the Armenian and Greek “victims of persecution”. He was to play a role in causing the arrest and deportation of many Turkish personalities. “The Chief Dragoman had always been in some sense the alter ego of the Ambassador in relations to the Turks. Mr. Ryan wrote, and it was more than necessary in armistice conditions that there should be someone capable of playing the same role for the admirals (Calthorpe and Webb)... I was as busy as any of my predecessors in maintaining touch with ministers and other Turks, collecting information, following the affairs of the non-moslem minorities and drafting countless telegrams and despatches”.

|

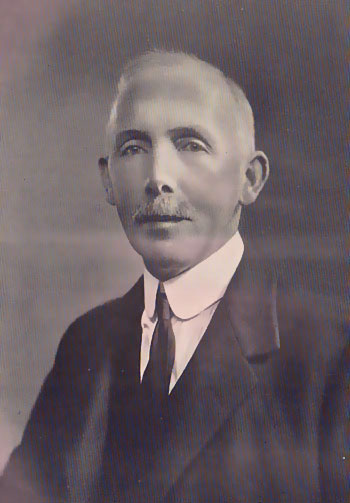

Sir Andrew Ryan

|

The Last of the Caliphs : H.M. Sultan Abdul-Mejid Effendi

|