The Interviewees

Interview with Bengi Su Ertürkmen Aksoy, August 2021

1- Your master thesis was about the Jewish quarter of Ankara. Did this community follow the general Westernisation trends through the 19th century in parallel with the other communities of the Empire and reflected this in their architecture?

Although it is located at the intersection of important trade routes, it is not very accurate to compare the city of Ankara and its inhabitants (with its varied non-Muslim communities) with cosmopolitan port cities such as Istanbul and Izmir and the communities living there. Ankara was less associated with the west due to the lack of direct relations. Rather than the modernity demanded by the modernizing individuals as seen in more cosmopolitan cities, the phenomenon of westernization was realized and this was mostly by the direction of the central authority. In other words, the transformation that took place in the city and in the communities in the 19th century Ankara was quite different from the more cosmopolitan cities of the Empire.

The Jewish quarter (and the Jewish community) of Ankara exhibits interesting features in terms of tradition, westernisation and modernisation. This situation can best be exemplified by the Ankara Synagogue. The Ankara Synagogue, built in 1907, was designed on a modest scale with a traditional Sephardic central plan scheme, unlike the monumental churchlike synagogues built in the same century in Europe. However, in the Ankara Synagogue there is an early example of the choir balcony, which was designed as a requirement of the choir tradition that started in European synagogues in this century. I should state here that there were and are not many examples of this modernist choir balcony application in the synagogues of the Empire. So here, this duality shows that the Jewish community of Ankara has undergone a transformation or lets say westernization but a rather cautious one compared to its counterparts in cosmopolitan cities.

2- Your recent PhD title is “Network and Modernity of ‘High Society’ in Urban Spaces of Istanbul, 1856-1896”. Were the date markers here connected with the end of the Crimean War, and thus increasing British / Western influence and populations and the end date possibly the seizure of the Ottoman Bank by Armenian nationalists and the later mob violence? Was it make it more manageable that you didn’t take this period till 1914?

As you said, the dates that determine the period of my PhD study starts with the end of the Crimean War, and ends with the Occupation of the Ottoman Bank. In addition to these, 1856 was the year that the Ottoman Bank was established. The period I wanted to focus on here was the period when non-Muslims and Levantines gained money and power, and had a say in the urban society and country administration, as a natural result of their increasing direct relations with Europe. The Occupation of the Ottoman Bank was found to be important because it significantly reduced the credibility and power of not only the Armenians, but also all non-Muslim communities and Levantines in the central authority and urban society. For this reason, in order to observe the activity areas of the communities in the modernization process, the period when they were strongest was found sufficient for the examination.

3- Prior to the Crimean War clearly the Levantine / High Society were smaller in number but still around. Were pleasure pursuits more ‘private’ such as in homes, clubs and theatre etc. Do you think the British presence, and in particular Ambassador Bulwer was a major impetus to discover the pleasures of water and the Islands?

We know that a considerable Levantine community lived in Istanbul before the Crimean War. Trade agreements made before the war, first with the British and then with the French and other European countries. With the Crimean War, the Levantine population scaled up. However, I find it somehow insufficient to attribute the shift in social activities from private (‘at homes’ events) to public spaces with the increase in the Levantine population after the Crimean War. I think that the important break was realized when non-Muslim pioneers, who gained power in the urban society (firstly the community they belong to) due to their increasing financial power, moved from their traditional neighborhoods to Pera -with a desire to live a modern life-. At this point, it is worth remembering that the presence of the embassies in that region had an important relaxing effect on living a more modern life in Pera compared to other quarters of the city.

Since I have read news that events could not be organized during the war, I think that a similar life continued in this part of the city before the war. However, there are also reports that the European officers who were in the city during the war demanded a modern life and introduced modern activities to the citizens. With the increasing interaction with the Europeans during and after the war, modern life gradually began to be included in the daily life of the urban society, and as a natural result of this, the places where the events could take place increased.

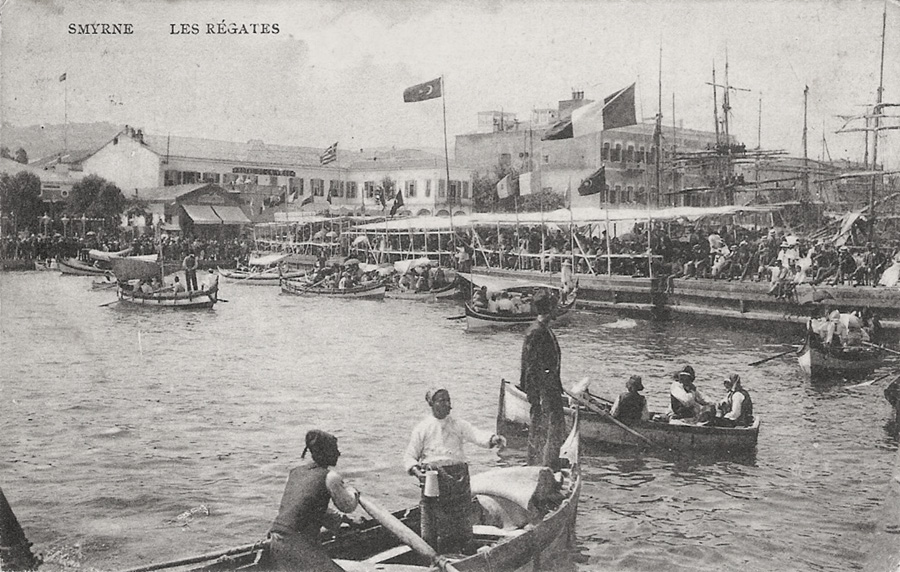

It was frequently mentioned in the newspapers of the period that the British community had a significant impact on the promotion of the activities of modern urban life to the citizens. Not only regattas, but also events such as horse races and cricket matches were started to be organized by the them in the Ottoman Empire. At this point, ambassador Bulwer became an important figure for the urban community since he was the pioneer who organized or patronized such events, especially the regattas.

4- Was the ‘High Society’ at that time fully inclusive of Moslems or do you think unless they were part of the retinue of the Sultan who was present in some of the regattas clearly, they shied away as most Ottoman officials wouldn’t be comfortable in the company of Western women who acted on a close par with their menfolk?

Muslim individuals, the majority of whom were high state officials, were included in the community I’ve defined as High Society because they’ve demanded and lived modern life in the second half of the 19th century rather than just being in the Sultan's suite. Most of the people mentioned here were educated in the west (mostly in Paris) or stayed in the west for a long time due to their state duties. They lived the modern city life in the west and consequently demanded similar life in their own empire.

It is useful to remind here that not every individual in the organizing committee (regardless of being Muslim, non-Muslim or Levantine) of the races belonged to the high society of the period. In my definition, the fact that a person was in an organization group of the regatta or any other event (or was present at the events to represent the Sultan or the government) did not make that person a modern individual or a member of the high society.

I think it won’t be correct to say that Muslim individuals in High Society were shied away in the company of Western women. On the contrary, for example, when the French Empress and her suite came to Istanbul in 1869, they were toured around the city by the Muslim bureaucrats. They’ve also accompanied and chatted with the Western women at the lunches, balls or soires and even danced with them at such events.

5- Clearly some of the resident Westerners / Levantines made a lot of money in their time in Istanbul and presumably there would be different reasons for this accumulation of wealth. Looking at the broad spread of how would you rate the proportion of those made money from money (lending / banking) as opposed to actual trade played out? Do any of the writings of the time point to social tensions growing with Christians and Jews seen as profiting from the ailments and financial irresponsibility of the Sultan’s?

Especially in the second half of the 19th century, non-Muslim and Levantine bankers owned a very large percentage of the money economy. The most important source of this income was gained from the stock market, speculation, and loans to the state (and the palace or harem, in other words). The gains from trade had been comparatively very small. In the 1850s the Ottoman government negotiated with British and French banks for a while in order to prevent the gain of the Greek, Armenian, Jewish and Levantine bankers (Galata Bankers), who made a significant amount of money by operating the debts with high interest rates. These negotiations resulted in the establishment of the Ottoman Bank. This was also a move to reduce the government's dependence on Galata Bankers. After the establishment of the Ottoman Bank, Galata Bankers also established joint stock companies to carry out banking transactions (and also infrastructure activities) by consociate different partnerships. So the aforementioned group continued to maintain its earnings through these new companies alongside their personal companies.

In the periodicals, foreign and domestic debts arising from the intense expenditures of the Sultan and the palace (harem) drew the reaction of the public. Accordingly, the high-interest earnings of Galata Bankers were criticized. Despite such articles, I must say that in my research, I did not come across any news or article that emphasize a growing social tension against non-Muslim and Levantine groups. This was probably due to the papers I’ve researched were published by Levantine groups. In addition, I should mention that probably in order to avoid possible reactions, the donations made by the bankers to everyone in need, especially their own communities, were constantly mentioned.

6- Your interactive web-based network-map showing connections of major families of Galata / Pera of the time is very ambitious in scope and presumably this was a supporting project to your thesis. Is this work still active and would you be open to widening this with support and collaboration with other organisations and adding additional data such as architectural, genealogical etc.?

I’ve produced this interactive web-based network-map to be able make true determinations on real people, places and relationships and to understand the demographic structure of the period. The goal was to avoid the usual generalizations in (architectural) historiography.

The map was developed based on my way of looking and handling the subject. It has a structure that can transform, change and develop with different ways of looking. I believe this map is meaningful as long as it is useful to different researchers and institutions. The map will always be open to the public as long as the platform provided by the web page is active. For this reason, I am always open to the cooperation and contribution of different researches and institutions.

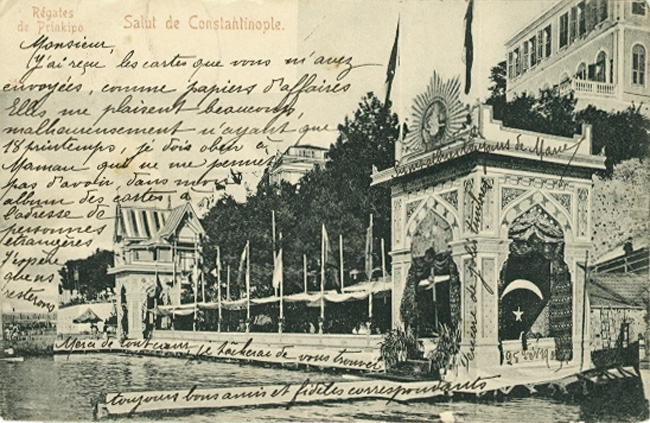

7- Prinkipo Island clearly developed as a result of the popularity of these regattas. Can we directly trace some of the characters who were involved in these events and their residence / housing investment in that island?

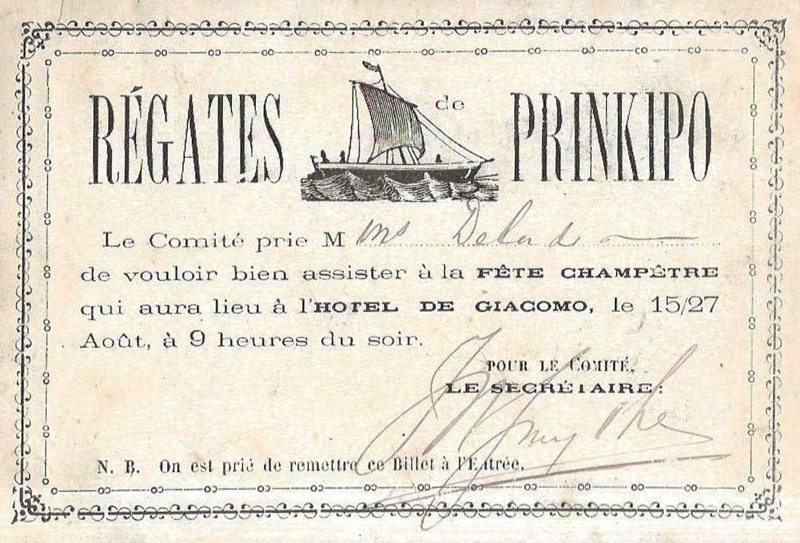

In my research on Prinkipo island, where regattas traditionally took place, I realized that this social urban event contributed to the development and transformation of the island. The transformation and development mentioned here can be exemplified as providing the infrastructure, building new and modern spaces, and making the island a fashionable summer resort in Istanbul. It has been seen that a number of individuals have pioneered this transformation. It is also seen that some of these people were in the organizing committee of the regatta. I can cite French Boudouy who arranged the pier and coastline on the island, the Greek banker Nicholas Zarifi, and the English banker Smythe as examples.

8- Is ‘High Society’ a problematic term. Can it be more a cultural than a economic level definition, so suggesting people who would take part / be a spectator in these regattas and similar pleasure activities organised.

I do not find the use of the term High Society problematic. What is important here is why to use and to whom I use this term. As I mentioned earlier, my definition of high society does not include all the bankers or bureaucrats of the period. This society includes people from different professions such as doctors, architects, theater owners and so on. As I said earlier, being in the organizing committee of a modern social event of the period such as the regatta or participating in these kinds of events as a spectator was not enough for an individual to be included in high society. What is important here is whether or not the individual lived and demanded modern city life and whether or not he influenced his surroundings with this new lifestyle due to their impact on the urban society.

9- You have accessed many of the contemporary newspapers of the period to analyse the regattas and similar activities of the High Society. Do you think there could be more information to tie in such as Ottoman Archives for various permission, permits, police records, foreign embassy records? Did you access any of these?

Because of my way of looking at it, foreign periodicals and trade annuals were sufficient to form the basis of the study. Of course, along with this, I came across many documents from the Ottoman Archives, especially in my research for the regatta. I should point out that these documents I encountered were the documents obtained by different researchers. My lack of knowing the Ottoman language was another reason for not prioritizing them. I believe the ones I’ve encountered are just a small glimpse of the rich records in the Ottoman Archives. I’m sure there is plenty of information on these subjects in the archives and they are waiting for researchers interested in these subjects to discover them.

10- Stratford Canning, 1st Viscount Stratford de Redcliffe was British Ambassador in Istanbul 1842–1858 and was very influential in fostering a pro-British view amongst the Ottoman bureacrats. Can you argue that this tenure was an important step in creating the conditions for these regattas to take place where the resident British were able to organise these and other festivities with full backing from the Sultan?

I can say that even during the time an ambassador spent in Istanbul, political dynamics changed rapidly. This is of course not only about the ambassador himself. The relations of the influential Muslim bureaucrat close to the Sultan was at that time, and with whom he had a closer relationship was an important factor. Of course, as you said, Stratford Canning was an important and influential ambassador. But I do not have enough information about his impact or influence on social activities, so it is not possible for me to make such an argument about him.

11- Would you welcome Levantine descendants ephemera which could shed more light on these various social activities?

Although social events and the effects of the events on the transformation of the space are very important issues, they are not studied enough. Therefore, the contribution of ephemera by Levantine descendants is always very valuable. So of course, I would be very happy.

12- You showed some photos of people engaged in rowing races etc. in the early republican period but these seem to have petered off perhaps mid 20th century. Do you think when the human memory of the more grand earlier regattas was lost the vision also evaporated and ‘organised pleasure races’ was no longer current?

In my research, I determined that the races were held until the second world war. I do not have certain information about whether these races took place after the war. But over time, it is possible to observe that regattas lost its glamour to other sport events (for example football). I don’t know how accurate or sufficient it is to associate this loss with memories, but I think that the preference of the sports event and the major transformation in the way individuals perform or follow those sports has caused this and this I believe is a common change all over the world.

13- Many of the buildings that record the living spaces of that Ottoman High Society still survive on both the islands and Pera / Galata. Do you think there is more research to be done to place these in a more human context connected with who lived in them, helping to raise their perceived importance and thus hopefully increased preservation awareness?

Of course, it seems to me that one of the most important reasons why civil architecture is not adequately preserved is that there is not enough study. The buildings in my researches mostly belong to the members of the Levantine and Non-Muslim communities. They’ve lost their owners over the years and left to the initiatives of different people or sometimes institutions. Nevertheless, I have happy news that can exemplify this awareness issue you mentioned. I believe, the two houses opposite the Ankara Synagogue, which I said earlier were the subject of my master’s thesis, have been better understood with several researches done about them including my research. Because today, a restoration process has started in these houses. I would like to think that we, the researchers and I have also played a role in this. So I believe the researchers and their research have the potential to create / increase awareness in understanding the value of civil architecture and the cultural heritage of any period.

14- What are you currently working on, if you wish to share that with us?

Currently, I am working on much smaller-scale research projects (in terms of period and space) compared to my dissertations. One of them is about the Beykoz region of Istanbul and the other one is about the visits to Istanbul of the French Empress Eugénie in 1868 and the Prince and Princess of Wales in 1869.

Another research that excites me is about the sports clubs active role in the transformation of Ankara’s social life and their locales in the first half of the 20th century, for which we won a research award together with my colleagues Beril Kapusuz Balcı and Oya Memlük Çobanoğlu.

Interview conducted by Craig Encer